Excavation at Star Carr in Yorkshire, bbc.com

If I had the brain capacity, I’d write a book called something grandiose like Infrastructure and Civilisation. To bring out just how important working infrastructure is to us.

You can’t have ‘civilisation’ – people living in towns and cities – without it. How did it grow, from the earliest actions to build shared causeways? We are handy, but it must be more than that.

I just read an interesting book called Inheritance: The Evolutionary Origins of the Modern World. It’s by Harvey Whitehouse, an anthropologist who also conducts psychology experiments on small children and co-compiled a database of hundreds of cultures already studied by anthropologists and archaeologists to analyse for key factors – as I said, interesting.

It made me reflect that both modern society and physical infrastructure require two things: co-operation between people (to build and maintain far larger social and physical structures than one person or even family could do) and sanctions, in other words ways to get people to do, or not do, things.*

Both have their origins well before homo sapiens, of course. Primates are largely social co-operators – and have strong views of what’s not fair, that they will go out of their way to punish. Sanctions for anyone not behaving well don’t have to involve written laws or dedicated police: for a social animal whose life depends on co-operation, disapproval works well on its own.

I grew up with a just-so story about competition being the motive force of progress, but it is much, much more interesting to look at how people work together.

It’s certainly my experience of infrastructure. 99% co-operation with some rules and regulation to force social-mindedness where necessary.

(And my current read is Progress, A History of Humanity’s Worst Idea!)

What’s the required balance of co-operation and rules for sustainable infrastructure?

*Whitehouse talks about why slavery did not in the end work out – why it’s more effective to get people to co-operate, when you grasp our basic psychology.

Legacy: A Decision Maker’s Guide to Infrastructure is published!

It’s a slim, elegant book aimed at councillors and C-suites to convey the realities of infrastructure, and the vital support a good Asset Management can provide to them.

Available as ebook or print on demand through Amazon.

‘Legacy: A Decision-Maker’s Guide to Infrastructure is not another technical manual. It’s a clear-eyed, call to rethink how we lead and make decisions about the physical assets that shape our daily lives – from water systems and roads to hospitals, parks, and transit networks.

Written by respected infrastructure thinkers, Ruth Wallsgrove and Lou Cripps, Legacy distills decades of frontline experience into practical guidance for those who carry the weight of stewardship. This isn’t about technology or buzzwords. It’s about responsibility. Clarity. Purpose. And asking better questions.’

Design by the wonderful Matt Miles – much gratitude again

see Resources

In case you haven’t caught up with it yet, ALGA’s ‘2024 National State of the Assets Report: future proofing our communities’ was released a week ago. You can download a copy of the Summary and Technical reports here:

Sometimes reviewing a report is a chore. This was a pleasure. It ticked all the boxes: it was very readable; honed in on the important issues and provided useful, verified data. It would be impossible for anyone to read this report and not gain a great appreciation for the pressures being faced by all councils, but especially smaller and regional councils, as they face the combined effect of asset ageing, climate change, increasing consumer expectations and more stringent regulations – and very little access to funding.

My overwhelming reaction, and it may be yours too, was to realise that better asset management is unlikely, by itself, to be sufficient. And this may be the most important take away. Asset Management is often presented as a panacea, it is not – but it is where we must start, for if we cannot manage effectively what we already have, how can we ask for more?

The good news is that this ALGA report indicates improvements are being made. How we express data has a major effect on how it is received. I particularly appreciated having infrastructure costs expressed per ratepayer. There was a time when we felt that large aggegate numbers had more impact and everybody tried to make their future costs as big as possible ‘to be impressive’, but expressing costs on a small personal scale, i.e. per ratepayer, enables greater understanding. We are more able to feel it. I also like the way that averages were dealt with. When I started work on life cycle renewal costs, realising that averages concealed more than they revealed, I put a lot of effort into calculating full age distributions. But ALGA has realised we don’t need to do all that work if we supplement the average with an indication of the extent of the most urgent of renewals. Very sensible. Indeed the entire report is very sensible. There is a lot of data, but it is carefully designed not to overwhelm.

It is a useful base for arguing for change. Change in the way we fund councils, change in the way we record and use depreciation figures are the first two that come to mind. What else would you like to see changed?

If you are planning to attend our Sydney celebration, please RSVP to: amis40@talkinginfrastructure.com so we can keep an eye on numbers – limited to the first 60! Event is free, includes food and discussion with Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda and a whole heap of old friends and colleagues.

Full update of the 40th year celebration events shortly!

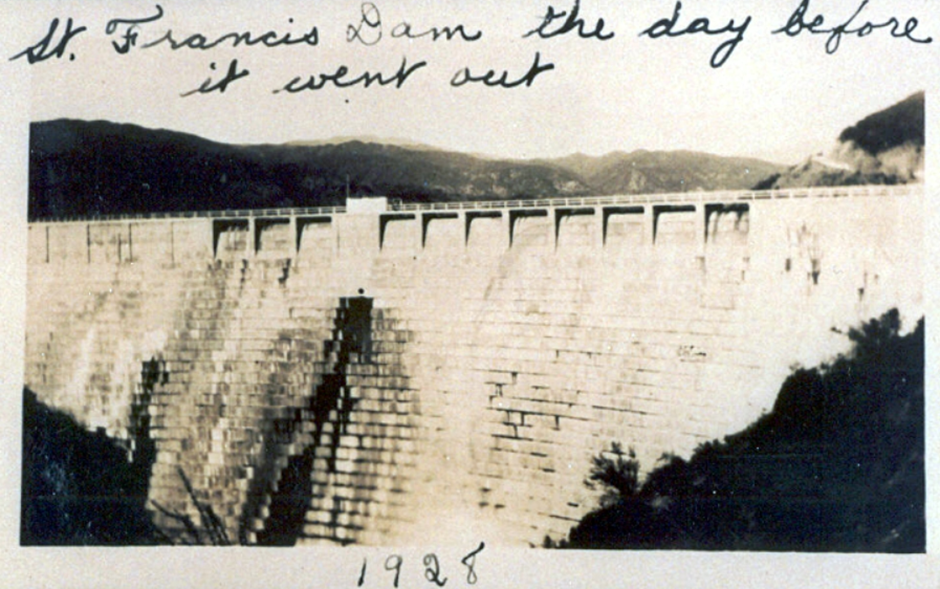

Last known photo of St Francis Dam before it collapsed, © scvhistory.com

You know when you hear something you never noticed before, and then hear about it again the very next day? (It’s known as the Mandela Effect.)

I mean, I saw Chinatown many years ago and so understood that there was a rotten heart to Los Angeles’ water supply, but I never thought about where the water comes from – or understood how it trashed a valley and its communities in the 1920s.

Originally called Payahǖǖnadǖ, meaning ‘place of flowing water’, Owens Valley is a now dry valley north of LA.

I work with enough hydro dams to be curious about dam failures – there have been a few catastrophic failures in the 20th century – so wanted to watch a PBS documentary about the total failure of St Francis Dam in the valley. It failed because of hubris. It did not make it past its first day in operation. But the documentary was about much more than the immediate collapse and the hundreds of people who died that day.

Los Angeles basically stole the water, buying up water rights surreptitiously and sometimes illegally. For some reason I can’t comprehend, it even memorialises the engineer responsible for the dam failure (and the overall aqueduct, which does still exist): Mulholland, of the Drive.

And the day after I watched the documentary, I read a review of a book titled Dust, by Jay Owens, using the Owens Valley as a 20th century example of humanity creating arid dust bowls where there were once thriving ecologies.

Metropolitan LA is a funny old place. I have spent plenty of time there as my brother moved to Azusa in the late 1970s, and retired to Orange County to the south. It was hailed as the city of the future once, but water is the big question mark, still. You would have to conclude that the LA basin is well beyond its carrying capacity, and perhaps always was.

Owens Valley, and St Francis Dam, seem suitable reminders of the challenge of sustainability. enshrined in the original BSI PAS 55 definition of Asset Management. The valley and its people – original and immigrant – paid the price for the development of a vast city region.

Not the first and surely not the last example, but a sobering reminder that water engineering is both hard, and not always on the side of the angels.

Thanks to Chad Dulac of Chelan County PUD, WA, for this steam-punk platypus

I just dutifully waded through a dismal history of the last five decades of British economic policy. Plenty of government mistakes, and nothing that really got past missing an empire. (The Tyranny of Nostalgia, by Russell Jones.)

Despite a less than adequate grasp myself of the mechanics of money supply and exchange rates, I wanted to learn lessons for we should be doing in future. And try to keep up more with Penny Burns, of course.

The book itself focused most on economic stability, and how that encourages good things to happen. Or at least doesn’t scare the horses. And something beyond short-termism and political self-interest.

But, at the very end, the author did have to conclude that successive British governments have done less and less on what truly underlies the ‘economy’: on developing skills, encouraging new ideas, and supporting infrastructure. On how to enable people to do interesting things, really.

And here is where talking about infrastructure comes in.

The physical infrastructure of water and waste water, power, transport and telecommunications isn’t something in its own right, assets for their own sake. It’s about enabling us to do what we need and want to do. Along with agriculture, education and health, it has to start with supporting Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. No-one too hungry or cold or isolated or poorly educated to reach for self-realisation.

In a country increasingly of “private wealth and public squalor” – used originally to refer to the United States – I come back to the sheer waste of potential in Britain, along with the heartache of poverty and lack of opportunities. It’s not like we don’t have plenty of really interesting challenges to apply our collective energy to.

Obviously no-one in the current British government has any kind of vision for community beyond their rich mates.

But what is our vision?

The peculiar antics of Elon Musk in late 2022 prompts, once more, the question of whether tech billionaires are really the best model for our heroes.

During Covid, plenty of people realised how dependent we are on carers, paid perhaps a millionth of what Musk pays himself. We clapped for a very different kind of heroics during lockdown.

Infrastructure is an intriguing mixture: it’s technology to keep our societies going, not primarily to make money. Managing it well involves caring for stuff. We are not carers in the traditional sense – and many of us are paid better than nurses or teachers.

Of course, technology innovation and looking after other people are very heavily gendered in our society: stereotypically, techies are male, carers are female. Making an obscene amount of money from exploiting innovation is masculine heroics; working till you drop caring for someone else is feminine heroics. (There are plenty of men in caring professions, but that doesn’t stop the stereotype.)

Sometimes I feel we’re trying to work out what kind of heroes we want to be in asset management. There are plenty who fancy the innovation techie route, getting all excited about ‘digital transformation’ (cf. the call this week for papers by ReliabilityWeb on the subject, for example) and, probably, the well-founded belief this is an easier way to make money. There are others, more equitably spread between women and men, who are sure it’s mostly about people.

We shouldn’t be particularly surprised to see crude stereotypes echoed in our own profession. A colleague recently described the problem of dominance in AM by “fat middle aged white men” (he said he was talking about himself, and the fat bit was a joke) – a dominance that doesn’t thrill me. I find myself more alarmed by the failure to learn our own lessons about what it takes to manage infrastructure, and rush into anything techie. As though, this time, technology innovation will sort out all the problems. Including the tiresome need to think about people.

But, then again, it’s surely the mix, the dynamic tension, between technology and caring which actually appeals to many of us; that brought us into asset management in the first place.

In their excellent book The Innovation Delusion, Lee Vinsel and Andy Russell challenge both innovation and heroes as ideals – and propose instead the maintenance mindset and how to sustain our “human-built world”. I think this is partly what they mean, this interesting mix.

PS Their Maintainers are still going strong, by the way, with some assistance from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Siegel Family Endowment – see www.themaintainers.org

I have known – and quite probably, so have you – many who have fought their way to the end of their studies, perhaps in medicine, law or teaching, only to find that their chosen field is something for which they are quite temperamentally unsuited and they need to start all over again. Fortunately, for those who wish to make their career in the management of physical assets, this fate can be avoided.

In Leadership Assets, Dr Monique Beedles takes you through four stages of an asset management career – from an Apprenticeship role where your task is to learn and you are leading yourself, through the next stage as Advisor where you lead others and your task is to establish credibility, and on to being an Advocate where you are now ‘leading people who lead people’ and your role is as an influencer, and finally, if you wish, a role as Ambassador where you represent an industry and lead a community.

You don’t need to be at the beginning of your career to benefit greatly from this book, although if you are, you are lucky indeed. Even those considerably advanced along a particular pathway will be encouraged by seeing how much further they may still progress.

Whatever spot on this spectrum you choose for yourself, you will not only find here a clear outline of the key ‘smarts’ you require: ‘tech’ smarts, ‘biz’ smarts and ‘people’ smarts, but also, and importantly, how to develop your strength in the ones you need. This is the main core of the book. It is brightly written, brief, to the point and immensely useful.

This is one of those books that when you find it at the end of your career, as I have done, you are left with a great desire to start all over again – and do it properly!

To coincide with our presentation on the Waves of Asset Management at the IAM Global Conference on June 15, Talking Infrastructure launches: TIki. The wiki for strategic Asset Managers.

To being with, while we build up the content, it’s read-only, but we invite you to join in with further development.

Organized by Wave, we aim to build up an unrivalled knowledge base on Strategic Asset Management, including access to the best of… Strategic Asset Management, Penny’s biweekly newsletter from 1999 to 2014, as well as more on Building an Asset Management Team, and through DAN and other networking with AM leads in North America and beyond. And don’t miss an episode of The Story of Asset Management, which for Penny was always about being strategic.

On Wave 3, Infrastructure Decision Making, we are using TIki to capture thinking on future friendly assets – better questions, some of them hard, particularly in this era of ‘Build Back Better’ trillions.

For Wave 4, we aim to start to nibble away at how to integrate infrastructure and planetary health, starting with the initiatives at Blue Mountains City Council.

TIki already has many pages, and many more to come. It’s easy to follow your curiosity, as well as backtrack via the trace.

Click on TIki in the top menu bar, and start your exploration now!

An Asset Management friend recently emailed me that her CEO had challenged her view of the importance of AM to their whole business strategy. “So asset management is improving our passenger experience? Asset management is improving employee engagement? Asset management cures cancer?”

While, on the other hand, even plenty of people with ‘Asset Manager’ in their job title act like their job is to manage the list of assets in an IT system.

ISO 55000 makes bold claims, that I think it cannot substantiate. That the same principles we apply to managing physical assets hold true to managing anything else of value, like financial assets, or people. I suspect that the good folks who wrote ISO 55000 may have no idea what that even means – or, put it this way, would you necessarily go to an engineer to tell you how to manage people?

So I do in practice think there’s a limit.

However, managing physical assets clearly is a huge part of running an asset-intensive organisation such as transit or power, or even a city. It’s certainly most of their budget and resources. If you can get that right, many good things should follow, like profit, customer service and, yes, engaged workforce.

But perhaps the real point is that to manage the physical assets well, you have to think about profit, customer service, and engaged workers.

To me, it’s obvious that it matters – it matters hugely that we do manage our essential infrastructure well, that not merely our economy but quality of life and planetary health depend on it. So we need a wider vision, an understanding of interconnections and dependencies, ‘the bigger picture’.

Asset management will not cure cancer. It has boundaries.

But managing the physical assets that underpin our society effectively is probably wide enough scope to be getting on with, don’t you think?

Recent Comments