Integrative Asset Management in Holland

Rob Schoenmaker, currently with Delft University, has been appointed to the position of Professor of Asset Management at HZ University of Applied Science. This is a brand new program, not part of engineering, business studies but entirely independent. The aim, in line with the integrative principle of asset management, is to span the boundaries between various disciplines. So he is involved in (civil) engineering, industrial engineering and management, data science, economics and international business management. The lot!

His role is to focus on research, to create long-term relationships with public and private organization, to get real life situations that can be studied and used in the various curricula. All with the end in mind: toeducate the professionals of the future using real problems and challenges.

User Stories

One of the first reaps of the harvest of spanning the boundaries between disciplines is the technique of ‘user stories’. Data scientists use this technique within their CRISP-DM[1]method to determine data mining requirements or goals. This technique has proven to be very useful to get to the core of what asset management professionals need to know.

User stories in ‘software speak’ can seem quite remote. Here it is in simple English. The official format of a user story is:

As <my role> I want <action/characteristic> in order to <reason>.

For example:

As a maintenance engineer I want to know the number of defects of component x in week y to understand the performance of the system.

It starts with a priming question –

What do you want to know/to do but never got the opportunity to find out/to do?

Professionals in this position can readily come up with dozens of questions covering what they really want to know – and why they want to know it. Rob then takes his harvest of questions, creates some order out of the chaos of stories and sorts them into certain categories, which in turn become input for the next discussion.

Behind finding the answers to the user stories lies the paradigm of ‘data-based, evidence-based’ and Rob says the real fun is to combine asset management with data science techniques.

“ What we intend to do, is to get long term relationships with public and private asset owners/managers in our region. We will do research on their areas of interest – this requires a budget, mind you – and we have lecturers-researchers work on the project, together with students. The lecturers-researcher can integrate the projects they are working on in the modules/courses.

Another way of working together with the asset owners/managers, is to define projects and apply for (NL/EU) subsidies. Once awarded this also results in a multi-year collaboration.

As an example: Together with my colleague of Data Science, we are now in the process of writing a proposal for risk-based, data-based AM in municipal sewage system management. This area is facing a lot of rehabilitation work in the coming decades, plus challenges caused by heavier rainfall, longer periods of dry weather, tighter budgets, pressure for transparency, etc.

Smaller municipalities often don’t have the budget for R&D, lack capacity (and often capabilities) to apply complicated AM techniques. And don’t know how to use the data they are sitting on. What we intend to do is to create a ‘fit-for-purpose’ (sorry: couldn’t find a better phrase) AM toolbox and incentivise inter-municipality collaboration. Again, asset management is doing this in close cooperation with data science – and we started off several months ago with collecting user stories.”

Universities in Australia have also been developing graduate courses in practical research methods and case studies as described by Rob Schoenmaker, but using ‘user stories’ for this purpose and feeding information back into curricular development is innovative.

This is question asking at its finest – providing both learning and teaching.

Talking Infrastructure has used a modified form of Rob’s ‘question and response’ format to establish what it is that our own multi disciplinary listeners want to know about infrastructure decision making. Responses are now being collated and you will be able to see the results in our first podcast episode “What do you want to know?”

[1]CRISP-DM:Cross Industry Standard Process for Data Mining (Chapman et al., 2000)

The first vacuum cleaner was famously the size of a room, now we have the roomba! As we make things smaller we don’t only change the size – we change the properties and hence the possibilities. What does this mean for scaling down infrastructure?

Innovators and entrepreneurs focus on how to ‘scale up’ on the assumption the same benefits will occur but that there will be more of them. Yet when we ‘scale down’, at least if we do this in a major way, we don’t get the same benefits only fewer – we get very different benefits. Take Quantum Mechanics. When we move to an atomic scale the generally observed and accepted rules of physics and mechanics cease to apply. Or nanotechnology where again as we get smaller we get significant – and very useful – differences in material characteristics.

What about infrastructure?

In the past, as we have scaled up, we have reaped greater cost efficiencies, albeit with some greater risks, however most of the features we were interested in stayed the same or got better – cost, reliability. An example would be electricity. For many years, as larger size generators were developed, they provided reductions in both capital and operating costs. Then we networked, joining the production in many separate plants. We developed the national grid. At each stage of scaling up, gains were made.

Now, with the widening spread of digitisation, scaling down is becoming not only a viable option but the desirable option – even for infrastructure. And as we scale down we find that, just as with quantum mechnics, the accepted rules no longer apply, and just as with nanotechnology, new and interesting properties arise.

Again take electricity as an example.

As we move from large, centralised, fossil fuel generation, to small, local solar generation, the first thing that happens is that we change the user- supplier relationship. And with this we change the economic power relationship (no pun intended). Where we used to have one large centralised provider making all the decisions, now we have the possibility of many smaller prosumers in potentially separate networks. The leading electricity providers are recognising that the need for their services has changed – from provision of energy using their own large scale assets, to the management of energy in smaller localised grids and with the assets of others! This may include, as an intermediate stage, large solar farms feeding into a national grid.

This presents a challenge to the grid and its ability.

This challenge was at the root of the perceived (although not explicitly recognised) problem behind the recent Finkel Inquiry. It was not, as was commonly thought, an inquiry into the future of electrical energy, but rather into the future stability of the grid itself, a grid set up to manage supply from mass, centralised, power generation.

Instead of the traditional system of generation- transmission – distribution – use, with solar generation provided more locally, the need for the transmission function (moving electricity vast distances) falls away taking with it the need for substations

As we move from massive large scale to small scale infrastructure, (eg solar energy, or mobile telephony) the whole nature of the infrastructure changes and that gives rise to many new and very interesting possibilities.

It may be that as we ‘scale down’, we change the nature of the supplier-user relationship so much that what used to be a question of how we contained the cost of generation and distribution becomes something quite different – but what?

There is even the possibility that when we are able to develop cheap, effective storage, electricity may cease to be ‘infrastructure’ at all. It may, instead, become an individual resource, something we own like a car or washing machine. Within the next decade it could be that solar cells, (or perhaps solar roof paint) and battery storage are in common use.

Nor is scaling down unique to electricity.

Peter Diamandis tells of Dean Kamen’s “Slingshot,” a technology which can transform polluted water, salt water or even raw sewage into incredibly high-quality drinking water for less than one cent a liter. It uses an evaporative process, effectively boiling the water and then distilling the vapor. It does this in a device about the size of a bar fridge that can use any form of energy – even methane from dung. It is now being distributed across the underdeveloped world by Coca Cola as part of their aim to replenish 100% of the water they use in their drinks. Want to know more? Other technological developments are occurring for the treatment of sewerage.

The upshot of these new technological developments is going to be radical change in the very shape of infrastructure as we know it and an equally radical change in the economics and politics.

What does this mean for infrastructure decision making?

How do changes like this feed into our forward thinking for infrastructure? Or to ask the same question in a more provocative way – what is the future for our existing infrastructure? Do we renew and replace, or do we change?

If you find this an interesting thought, watch for our forthcoming podcast series where we translate the wider world challenges into what we need to think of with respect to infrastructure decision making.

Yesterday I posted IDM in Pictures 3/12. IDM stands for Infrastructure Decision Making. You can think of IDM either as the next stage after strategic asset management or as an intermediary stage between 20th century physical infrastructure and a 21st century that will be increasingly cyber or cyber augmented, but the shape of which we do not yet know. Infrastructure decision making is about asking those questions that will help us make the adjustments we will need to make.

Yesterday I posted IDM in Pictures 3/12. IDM stands for Infrastructure Decision Making. You can think of IDM either as the next stage after strategic asset management or as an intermediary stage between 20th century physical infrastructure and a 21st century that will be increasingly cyber or cyber augmented, but the shape of which we do not yet know. Infrastructure decision making is about asking those questions that will help us make the adjustments we will need to make.

For example, consider the rise of e-sports, a.k.a competitive video gaming. What impact might this have – on physical sports and on our sports infrastructure? Already a $1.5 billion business, it is increasing at 30% p.a. and projected to continue this rate of growth for at least the next five years. How many of our recent stadiums and those now being built have factored in this rate of growth for e-sports – and the possible concommitant impact on physical sports? So far it has mainly affected Asia and North America. However Australia joined the excitement early this year with major tournaments in Melbourne and Sydney. Do our current sports stadiums lend themselves to housing these events? The physical requirements of e-sports in Sydney (pictured) required the design and construction of a purpose-built elevated stage housed in a movie theatre complex. E-sports require high speed internet access and present high intensity light shows, music, dancing along with the video gaming competition. In Asia and North America they can attract crowds of 100,000.

In times of uncertainty we often seek comfort in resorting to what we have always done and are therefore confident that we know how to do. This may give temporary relief from the stress of the unknown but it only pushes the decision making further out whilst making the decisions harder when they come due again, and this is likely to be much sooner than we think. The consequence of doing this in the recent past may be why we are now hearing the term ‘playing catch up’ from our political pundits like Jeff Kennett. I don’t like this term, or the idea it implies. Why catch up when by the time that we do, what we are catching up with will already have passed?

The earlier we pay attention to future issues and start thinking – and talking- about the changes needed – in mindset, technology, principles and practices – the easier our adjustment task will become.

Big data is a route to Abundance, but let us take care, data makes a great servant but a dangerous master.

If we respond to data outputs uncritically we make data our master. Yes, algorithms are becoming ever more complex and difficult to understand – and therein lies the problem. Unless we are able to understand HOW a decision was made, algorithms are just dead dangerous. There are really serious problems of people being denied access to medical or social assistance or being jailed because an algorithm deemed it so. Less serious – but funny! – is the story of two booksellers on Amazon using pricing algorithms that resulted in a 1992 out of print book on the evolution of flies rising to over $28m. A post graduate student interested to buy the book first noticed that where second hand copies were listed at $35, new copies were then over $2,000. When he went back the next day, the price had risen even more, and so it continued. Studying the prices, the student realised that one seller had set his pricing algorithm to be fractionally less than his main competitor in order to attract sales. the other bookseller had set his algorithm to price this book at slightly more than his main competitor. Why? We don’t know but the student suggests (in his blog where he writes it all up) it might have been because the seller didn’t actually have a copy of the book and would have to source it should anyone order. Since the premium of the one seller exceeded the discount of the other, the price kept rising. It took this research student to notice what was happening – not the booksellers, who were, of course, on autopilot. What damage could occur in your work if you are on autopilot?

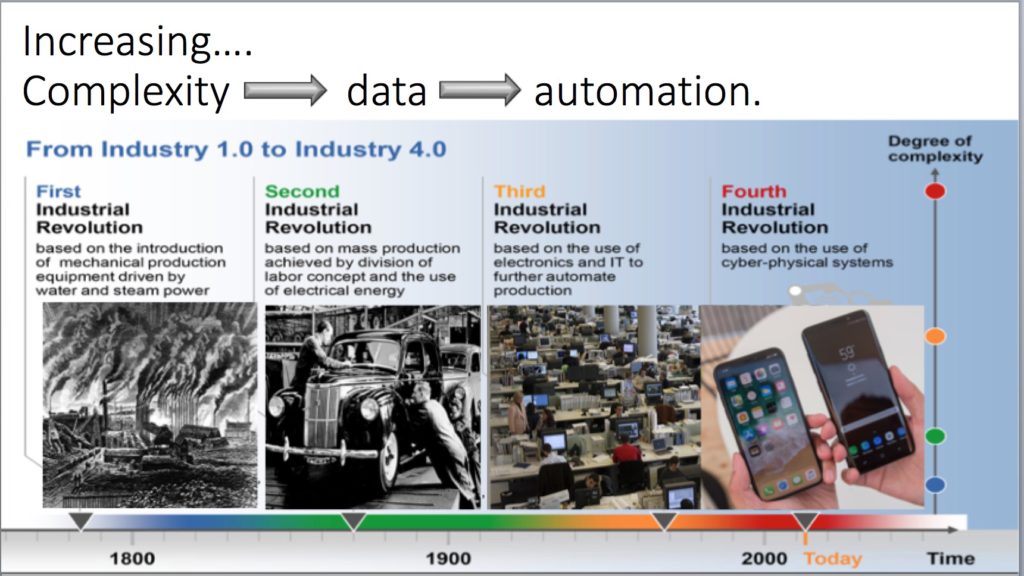

The ability of big data to deal with increasing complexity is nevertheless a great advantage. Consider how we have moved since the first industrial revolution.

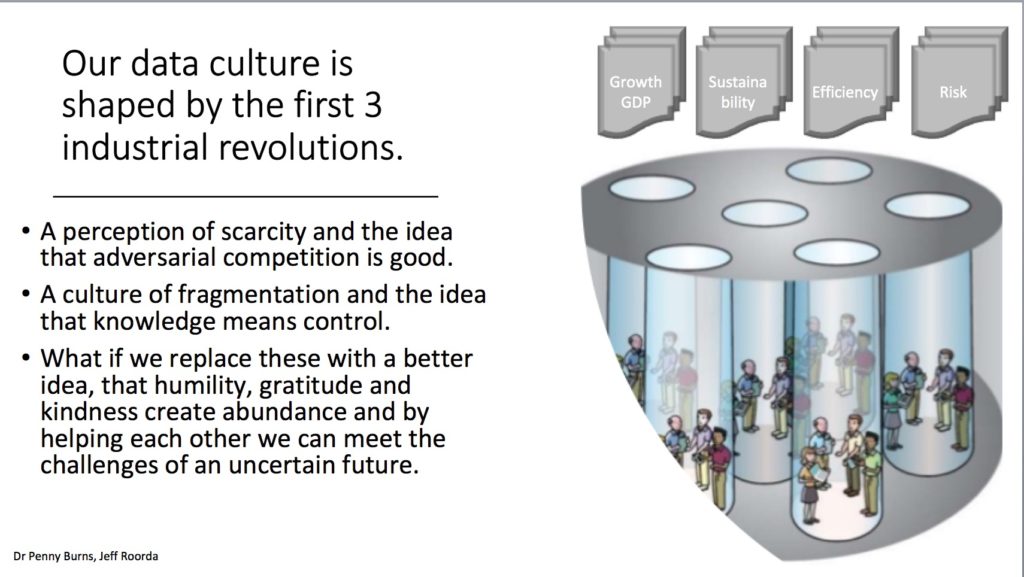

Our data culture is shaped by the first 3 revolutions. This has given rise to two attitudes or mindsets that are no longer acting to our advantage.

- A perception of scarcity and the idea that adversarial competition is good. But we are about to embark on a new world of abundance – as well described in Jeremy Rifkin’s “Zero Marginal Cost Society”. This is requiring businesses to change their business models. We know it as ‘disruption’ but it is more than that, it is opportunity.

- With increasing specialisation we have developed a culture of fragmentation and the idea that knowledge means control. Now that we are able to share knowledge so much more freely, we are able to develop better models, a more fruitful culture.

- This means that we can start to explore replacing these old ideas with a better idea, that humility, gratitude and kindness create abundance and by helping each other we can meet the challenges of an uncertain future. These are not really new ideas. During and just after the second world war, Londoners who had survived the blitz, now faced the problem of recovery. Instinctively they knew that, just as they had survived the war through helping each other, this was also the way that they would meet the uncertainty of the future. But as people became richer, they became more selfish and the initial rate of gain slowed. The way of the future is through collaboration. Harvard studies, as reported by Shawn Achor in “Big Potential”, have clearly demonstrated that teams of collaborating individuals have it all over geniuses. In fact a team of average intelligent people who ‘get on with each other’ well exceed the performance of a team of geniuses.

- This is the real message of ‘big data’ – together we can do more than we can do alone.

The possibilities of big data are impressive but let us not get carried away.

Not only is there the danger of trusting in the results of data manipulation that we do not understand (cf the many studies showing the dangers of ‘private’ algorithms that are not open to analysis), but there is the greater danger that we put our faith in aiming at ‘data’ outcomes (e.g. KPIs) rather than people outcomes.

So let us put our effort into better measurements of what really matters – better (i.e. more relevant) data. This will inevitably mean using non-dollar measures – and judgement.

Discussion today tends to conflate the benefits of greater use of digital data and digitisation itself. Both are valuable, and both impact infrastructure decision making, but they are not the same.

There is currently much discussion of loss of work opportunities through the use of robots. If our decisions are driven purely by data, then robots can do a great job. But if we want our decisions to include values such as kindness, compassion, and fairness, then we need people.

We appreciate the benefits of big data but do we really want to live in a world without kindness, compassion and fairness?

When computerisation first appeared on a large scale, we eagerly adopted it – and used it to carry out the same processes we had used bc (before computerisation). It was many years, in some cases, decades, before we realised that the real value of computerisation was to adopt completely new processes for new outcomes. Today the power of digitisation for connection is still being recognised. We eagerly embrace ‘smart technology’ in our cities – but are slower to recognise that connection can be used to bypass the city. That is we are increasingly able to ‘live, work and play’ in the suburbs, or the country, improving our lifestyle opportunities and reducing environmental costs. But first we have to see it.

INFRASTRUCTURE DECISION MAKING (IDM) IN PICTURES

DON’T MISS ANY OF THIS NEW AND IRREGULAR SERIES, JOIN THE TALKING INFRASTRUCTURE COMMUNITY (it’s free) AND RECEIVE OUR FORTNIGHTLY NEWSLETTER TO KEEP YOU UP TO DATE

There was a time when I would be in and out of an art gallery in 30 minutes, bored. I looked, but did not engage. Then at a Picasso Exhibition, i found paintings that I really liked, but also many that turned me off completely. After viewing all, I went back and studied these two groups and asked Why? Now galleries are no longer boring. I apply the same process to conference talks. I note all the new ideas, the new linkages that really please me and write them down so that I can think more about them later, and I also note those statements that drive me nuts, and I think about these as well. No prizes for guessing what category the ‘heretical questions’ in the last post fell into.

There was a time when I would be in and out of an art gallery in 30 minutes, bored. I looked, but did not engage. Then at a Picasso Exhibition, i found paintings that I really liked, but also many that turned me off completely. After viewing all, I went back and studied these two groups and asked Why? Now galleries are no longer boring. I apply the same process to conference talks. I note all the new ideas, the new linkages that really please me and write them down so that I can think more about them later, and I also note those statements that drive me nuts, and I think about these as well. No prizes for guessing what category the ‘heretical questions’ in the last post fell into.

But the IPWEA Congress this week, ‘Communities For the Future, Infrastructure for the Next Generation’ was far richer in yielding good new ideas, thoughtful linkages, and new ways of expressing accepted ideas so that they come to life and are taken out of the realm of platitudes. These deserve a far wider coverage, and so, with the support of our podcast partner, the IPWEA, we will be bringing you these ideas, and many others, in our forthcoming podcast series. Watch for it!

Or better still, join the Talking Infrastructure Community (click here) (its free!) and you will be the first to know when we launch.

A closing note: At an after lunch session in Parliament House many years ago, the talk was so boring I found it a hard job to keep my eyes open. Yet my colleague was riveted! He was listening intently and taking notes. At the end I sighed and said ‘That was a really boring talk’. ‘Absolutely’, he agreed. Surprised I responded ‘But you were riveted, paying great attention, taking notes, how come?’

His reply? ‘To make so boring a presentation, there must be many things he was doing wrong. I just wanted to figure out what they all were!’ Be engaged!

A heresy is a belief or opinion contrary to the orthodox (usually for religion, but applicable more generally) Here are some heretical questions in the asset management/infrastructure decision making field.

A heresy is a belief or opinion contrary to the orthodox (usually for religion, but applicable more generally) Here are some heretical questions in the asset management/infrastructure decision making field.

Heretical Question 1. Spend better or spend faster? An economist speaking at the IPWEA Congress in Canberra recently, argued that a greater spend on infrastructure was better ‘performance’. But is it? Jeff Kennett, former Victorian Premier, complained that 26% of funding allocated for capital construction had not been spent. He blamed over cautious bureaucrats. Both are focused on the size of the spend – and not what the money is being spent on. Is this really in the community interest? Or is this attitude (not confined to Australia) a contributing factor to the increasing evidence that infrastructure funds are poorly planned and many demonstrably lacking in justification? (cf Joseph Berechman ‘The Infrastructure we Ride On’ 2018)

Heretical Question 2. What is the purpose of infrastructure? And what should it be? Wearing our ‘better angels’ halo we say we are building for the future, but is this really true? If we were, would we not have a well developed vision of the future that we wished to create, and an infrastructure decision process that enabled us to plan to achieve it – and to adapt those plans as changes occur? Where is that vision? Where are those decision processes?

Heretical Question 3. The pipeline. An economist spoke of waves of capital expenditure and was concerned at the lack of a pipeline of projects that would maintain construction activity in the near future. Another speaker commented to the effect that Australia should ‘prioritise infrastructure’. But should it? Why? A pipeline of construction projects will ensure work in the construction industry. But the construction industry represents only about 10% of total employment. Why should we spend massive amounts of capital to ensure the jobs to privilege such a small section of the economy?

Heretical Question 4. Multipliers. You might argue that construction expenditure generates much more by way of multipliers – three times as much according to one speaker. Really? Where is the evidence for this? Many people blithely quote figures such as this, but cannot justify them. Construction expenditure does create jobs. ANY expenditure creates jobs. If the people who receive the income go out and spend it, other people benefit. This much makes sense. But how much of a large construction contract goes to the rich who may save rather than spend, and how much of the rest goes to workers who do not know where their next job is going to come from, and thus will tend to save more than spend? Wouldn’t a permanent maintenance job do more good for the economy than a short term construction contract. Or the same amount of money spent on nurses or teachers?

Heretical Question 5. Supply driven infrastructure. Jeff Kennett argued that we would do well to follow up projects with more projects to take advantage of the, now unemployed, workers completing the first job. In other words build infrastructure to provide jobs. Is this sensible? Tasmania in the late 1980s came to grief over this. With little employment in the North, infrastructure projects were created to provide jobs. The projects not only provided work for the unemployed in the north, but they attracted others from around the state so that when the project finished, there was now a bigger pool of unemployed, demanding a bigger project – and so on. Now most of the Tasmanian population is in the South so the infrastructure was largely underutilised. As a result of this expenditure, the state came close to bankruptcy. So, is this really a sensible idea?

Heretical Question 6. Vision/Plan. We have a tendency to use these words interchangeably, but is this sensible and safe? A plan is a set of actions designed to secure a goal or objective. A vision is an idea of some future state that we would like to achieve. Affordable healthcare could be a vision. A set of projects including asset and non-asset solutions could be in a plan. As technology, demographics, environment, governance and public attitudes change and information is acquired, we would have a succession of plans, all adapting to the current circumstances but addressing the vision. The vision may be a 50 year vision (even a 7th generation vision) but we would surely not wish to commit ourselves to a 50 year set of projects conditioned by only what we know now.

Feel free to add your own heretical questions.

Media articles often leave infrastructure questions dangling. QUESTIONS ARISING is an opportunity for those of you who read widely and keep their eye on what is happening to identify these articles and the questions that need to be answered. These can then be addressed in our forthcoming podcast series, so get involved – add your questions to those listed here, suggest possible lines of development, add new media articles along with the questions they raise. Sources may be the daily journals, the web, podcasts, radio, TV. Plenty of scope!

Media articles often leave infrastructure questions dangling. QUESTIONS ARISING is an opportunity for those of you who read widely and keep their eye on what is happening to identify these articles and the questions that need to be answered. These can then be addressed in our forthcoming podcast series, so get involved – add your questions to those listed here, suggest possible lines of development, add new media articles along with the questions they raise. Sources may be the daily journals, the web, podcasts, radio, TV. Plenty of scope!

Here to introduce our first QUESTIONS ARISING are two items identified by our Business Development Manager, Ian Spangler.

1. The Economist’s Intelligence Unit’s recent report on “Preparing for Disruption: technological readiness ranking, 2018”, places Australia in the top ten for the historical priod (2013-2017) BUT it forecasts that in the next five years, Australia, Singapore and Sweden will take over as the top-scoring locations. The ranking is based on the number of mobile phone connections and internet access.

Questions arising.

- Is this enough to ensure technological readiness?

- What else should we be looking at to test readiness?

- Australians, who are not easily overawed by authority, may well joyfully take up the idea of disruption, but to what end?

- How can we tell whethe our innovation is well directed?

- What else? Add your comments below.

2. The small homes project was recently launched in Melbourne. The RACV reports that “from the 1950s, Australia’s average house size more than doubled to 248 square metres at its peak in 2008-09. Then last year something strange happened: the size of new builds dropped. Over the past 20 years, median house prices across the country have gone up by more than 300 per cent while weekly wages have only increased 121 per cent. Rising cost-of-living pressures are also draining our bank accounts, with the average annual energy bill in Victoria now around $1667. Building and running a big house is not cheap and it is not great for the environment.”

Questions arising

- The ability of the demonstration small home to provide so much convenience in such a small space is its use of 4G and 5G connectivity. How do you see this affecting futur constructions?

- Will we continue to reduce the size of our dwellings? If so, what factors may come into play? If not, why not?

- If our dwelling size does decline markedly, what impact might this have on other infrastructure?

- Other Questions

How might drones affect your life cycle?

Understanding the life cycle – from asset creation to maintenance, to disposal and/or rehabilitation and reconstruction, is a fundamental concept that many need to know. But different groups need to know it in different ways. We fail to communicate if the language we speak is not the language the listener understands. So consider some of the different needs.

- Elected members and all political decision makers need to understand the impacts of life cycles in terms that they can relate to – current and future service delivery and risk. They need to know this in broad terms, but they do not need the technical details.

- Policy, planning and finance people need to understand how to measure costs and timing so that they can plan to match future revenues and expenditures, They need to understand that predictions from our models are based on ‘average’ economic life cycles. Here we face a dilemma. More closely specifying our asset groups enables more accurate descriptions which helps to determine more accurate economic life averages. But it also reduces the size of each asset group and the reliabiity of averages diminishes as the numbers in the group diminish.

- Technical people need to understand it in terms of long term optimisation rather than short term. Their knowledge need is not so much dollars as technical intervention events, e.g. maintenance or renewal.

Understanding the life cycle in all these ways is essential to ‘keeping the show on the road’, and all of the above groups have taken this as their objective.

But the ‘day after tomorrow’ requires more.

Those of us advising Infrastructure Decision Makers need to do more, we have to be able to anticipate the nature and impact of changes in the life cycle itself. Along with elected members, policy, planning, finance and technical folks, we are concerned to enable functionality today and tomorrow but, in addition, we also need to ensure that we are able to take advantage of technological options and anticipate demand changes so that we may understand the changes in the life cycle itself, arriving the day after tomorrow*.

*And for more on future change and its impact on us see the coming IPWEA event in Sunday’s weekly round up!

Recent Comments