I have just been to the 30 year celebration of the Institute of Asset Management (IAM) in London, where we also marked ten years of ISO 55000. This was held jointly with the Global Forum on Maintenance and Asset Management (GFMAM) – representing AM and AM-minded maintenance societies worldwide – with representatives from IPWEA and the Asset Management Council. A time to reflect as well as celebrate!

Russ Seiler of Grant Public Utility District (one of the Columbia River hydro utilities in the Pacific North West) reflected on his journey since 2016. Starting from scratch as an Asset Management lead, under Russ the team at Grant has looked at asset inventory, Wave 1, and the absence of basic asset data. It then focused on the AM ‘system’, as in ISO 55000, and the idea of building AM artefacts. (Wave one-and-a-half?) But, encouraged by Penny’s 2023 book on the beginnings of AM, he realised that neither were really the point.

His conclusion after seven years? “If your asset management program never affects the money being spent on assets, your program should and will be terminated.” AM creates the machine that produces the plan, a better plan for the assets. Everything else is just a means to that end.

It’s the AMP process, ok.

I have trained many 1000s in the last 14 years, in the USA and elsewhere. And that’s what I have found, too. Too many get caught up in asset data – which is important, sure – and documents such as the AM Policy and SAMP, which are also important. But that is never what Penny meant by Asset Management.

And ‘plan’ doesn’t just mean what proactive maintenance you should do, or what you need to spend capital on to sustain your existing asset base. It’s also what if any new infrastructure we require. It’s whole of life and system-wide. It’s big.

Have we been tinkering at the edges while the world changes around us?

Penny and Ruth at AM Peak gala dinner, April 16 2024

Since I last posted I have spent a month celebrating 40 years of Asset Management in Australia with Penny, Jeff and Gregory; gone to one of my favourite conferences in Minneapolis; taught an advanced AM course to some sophisticated AM practitioners in Calgary, as well delivering to as a post ISO 55000 certification client in California.

I have been thinking about where AM needs to go next, at the same time as worrying that things have not moved far enough.

And it just keeps coming back to: We Need to Raise our Game. And not because what Penny kicked off four decades ago hasn’t made a huge difference already.

But I want us to do more.

First, to effect what Penny set out to do through Talking Infrastructure: to look up and out, to make a difference to key decisions on what infrastructure we really need.

Secondly, as I start to unwind from delivering basic AM training – something I have loved doing for nearly 14 years now – I reflect on our competencies.

This kicks off a series of questions and reflections on what we want to change, and how to do it.

How to interest existing AM practitioners in upskilling on risk, data analysis, culture/ system change, persuasion, strategic thinking?

How to find people who want to challenge the status quo on infrastructure projects?

What can we best offer from our collective experiences to support better decision-making?

I am looking forward to this!

Come and meet Penny and Talking Infrastructure in person! Watch this space for additional details, but here’s the programme so far:

April 15 & 16 AMPeak, Adelaide. Penny and Ruth will be at AMPeak.

April 18, Stantec, Brisbane

April 19, PACoG, Brisbane. Asset Institute, QUT, 11am- 12.30, followed by lunch. Join Joe Mathew and Kerry McGivern along with Penny and Ruth to discuss what we’ve learnt in 40 years – and look forward to the next 40. Includes a look of what is happening with asset management internationally, in this big year for AM.

April 23, Blue Mountains City Council, Katoomba, 10am to noon. Seminar with Jeff Roorda on Blue Mountains City Council planetary health and disaster recovery experience, plus update on the new advocacy project underway by IPWEA Roads and Transport Directorate (IPWEA RTD – NSW/ACT), on Lessons Learned from Disaster Recovery, to assist NSW Councils work with Local, Strate and Federal Government Agencies.

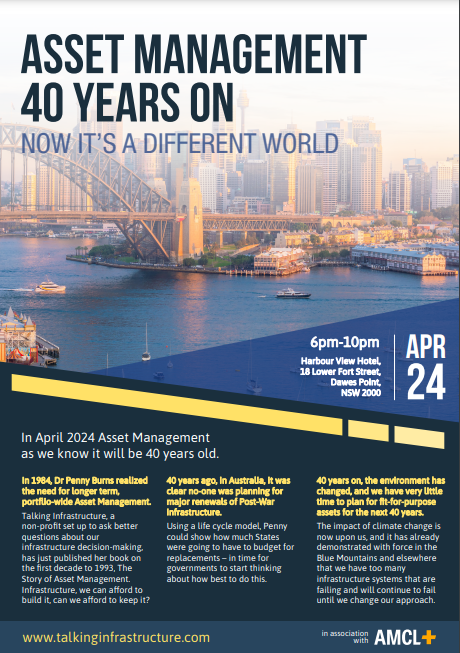

April 24, Sydney event, Dawes Point. 6-10pm Harbour View Hotel, 18 Lower Fort Street, Dawes Point, NSW 2000. Using the recent experiences of the Blue Mountains City Council, Talking Infrastructure is holding an event in central Sydney to call for urgent changes in all of our asset mindsets and tools to ensure planetary health, biodiversity and climate change resilience. Meet with Penny, Jeff, Gregory and Ruth, plus local IPWEA. Food provided thanks to AMCL.

April 30, IPWE, Melbourne. Presentation by Penny. Penny and Ruth will be at IPWE until May 3. There will also be a dinner out in Melbourne for TI friends and colleagues – please let us know if you would like to join us. And bring along your copy of Penny’s book to get signed!

If you are planning to attend our Sydney celebration, please RSVP to: amis40@talkinginfrastructure.com so we can keep an eye on numbers – limited to the first 60! Event is free, includes food and discussion with Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda and a whole heap of old friends and colleagues.

Full update of the 40th year celebration events shortly!

Join us at the Harbour View Hotel in the Rocks and help celebrate with finger food and drinks – plus Penny and Jeff on what we have learnt from the last 40 years to help us meet the challenges of the next 40.

Many thanks to Richard Edwards, Lynn Furniss and Matt Miles of AMCL

Penny Burns and Talking Infrastructure will be on the move in April to celebrate 40 years of Asset Management, and look forward to the next 40.

Adelaide April 15 & 16, Penny and Ruth will be celebrating at AM Peak.

Brisbane events April 17-19

Sydney April 24, venue TBC: Asset Valuation in a time of Climate Crisis. Including Jeff Roorda on how Blue Mountains City Council is taking a radically new approach, as well as Penny on how we must rethink our AMP modelling.

Melbourne April 30, IPWC. Penny speaking on the opening morning of IPWEA conference

Wellington May 4-6, events to be announced

Let us know if you are interested in meeting up in any of these cities.

See you in April! #AMis40

One of my great pleasures in life is to sit in a café and talk infrastructure. A popular topic, even before Lou Cripps came up with the idea Asset Managers are platypuses, is what makes an effective one? Or even what attracts us in the first place.

Who are ‘our people’?

To defend us from accusations of exclusivity, I need to point out that it’s not about what you studied at university, or which country you grew up in. Good Asset Managers are ‘anywheres’, as Ark Wingrove put it.

This is, of course, a Serious Subject, as we desperately seek to switch to a future-friendly mindset; seeing the bigger, longer picture around physical assets. But it’s also kinda fun to think about the difference that makes a difference.

Like the AM team who came on one of my courses and took me literally. We teach whole life costs, cost-risk optimisation, thinking in risk, and how information is all about decision-making. But I don’t think most attendees go away and start actually doing any of that. This team did.

One reason people don’t try whole life cost modelling, or risks in $, is because they think it’s too hard before they even start.

But my best students – well, if that was how you do Asset Management, they would figure out how to do it. When I later asked Todd Sheperd how they quantified asset risk, he said he looked it up on the internet. After reading a recommended book and going on a recommended course. (As I said, he took me literally.)

Yes, he must have had the confidence to believe he and his team could figure it out. But I think it’s more than that. It’s about curiosity and openness to learning.

It also involves a belief that if I don’t know something, someone else may have worked it out, maybe in a completely different context. We can learn from others – like 17th century gambling mathematicians, or stock markets traders.

Or actuaries. It’s as if 99% of attendees on AM courses have never heard there is a whole profession who have worked out how to put $ on risks.

Sitting in a café recently with Todd and Julie DeYoung talking about infrastructure, we also recognised another quality: interest in what we can learn from people doing something that’s not exactly the same as what we’re trying to do. Like wondering what we can learn from assets that aren’t exactly what we have – instead of deciding ‘our’ assets are so special there is nothing we can learn from others (and the processes of AM planning and modelling don’t apply to us).

In other cafés years ago with another old AM friend, Christine Ashton, we thought it’s about pattern matching. About looking at a problem we had, and the kind of technology approach it needed, as opposed to a fixation on a particular software tool, for example. What kind of problem is it? What sort of tool could help?

To me that’s linked to 80:20 thinking, but I suspect that some of my best AM buddies are better at details than me. It’s happily straying into the unknown, instead of trying to force everything to fit into what you already know.

I love (nearly) all of my students, of course. But not all of them turn out to be my sort of café people.

Shout out to yet another recent café and Janel Ulrich – her of the ‘can we develop our SAMP in the next 12 hours?’ (yes, of course we can). I love the way she loves ‘our kind of people’, in all our quirks and heartaches and irrepressible openness.

Others who will recognise their café contributions include John Lavan and Manjit Bains. And Penny, with whom too many of these café conversations have to be virtual.

My colleague Todd Shepherd and I had a brainwave* last year to restructure how we teach Asset Management – not as a line that starts with investigating capital needs, the conventional beginning of the asset life cycle, but from where we are now. That is, right in the middle of maintenance. We are always deep in maintenance needs.

It makes more sense of the history of AM, straight off. It was not people writing business cases, or design engineers, who realised the urgent need for something different. It was maintenance, post World War 2, and then Penny Burns and the problem of unfunded replacements and renewals in the 1980s.

If Asset Management has waves, we might suggest what Wave Minus 1 was. Wave Minus 1 was hero engineers, from the Industrial Revolution on, building heroic infrastructure – Bazalgette and London sewers, Brooklyn Bridge. Sewers and bridges are both good things. But they are not quite such good things if they leak or fall down because they are not maintained or renewed.

With infrastructure, it is not enough to start; you have to see it through.

Penny used life cycle models to understand the extent of renewals, and increasingly I don’t feel anyone is really doing Asset Management if they do not use such models. Of course it is called life cycle for a reason. There isn’t an end, only another cycle.

But now I fear that starting at the beginning of one lifecycle in our teaching still makes it sound as though it is the creation of infrastructure that’s the important thing. We have not really got the cycle bit across enough, at least to the average engineer we teach. What comes after construction is still a vague future state, that is someone else’s problem.

And, not at all coincidentally, that’s also the point of the circular economy concept. There is no meaningful product end, and we are right in the middle of the mess we already built.

It is not a straight line into the future, where we set assets in motion and let them go. Longer term thinking, long-termism, has to think in cycles.

*Almost certainly it was Todd’s brainwave, which I managed to catch up with.

In 2024, Asset Management turns forty.

One key question for me this year as an Asset Management practitioner is time itself, and how we act with the future in mind.

The innovation of Asset Management is very largely about time. Penny Burns created AM to look forward in time and consciously choose whether we needed to renew like-for-like, or should manage our assets differently in future.

Forty years ago, we were not thinking about climate catastrophe, and we were only just at the start of the IT revolution. (I had only just seen my first PC, and the world wide web, smart phones and terabytes of data storage for $50 were barely pipedreams.)

But the question of longer-term thinking has in some ways gone backwards in our societies since then, not forwards.

The vast majority of infrastructure organisations still only have very short term asset plans, and almost no asset strategy. More have, must have, 3- or 5-year plans now, thanks to AM as much as anything. But the 15 to 20 years plus strategic view that Penny proposed is still a challenge.

And shockingly few agencies even use life cycle modelling to project the very basic realities about the timings for replacements, let alone a mindset of always asking ‘And then what?’ of our day to day and year to year asset decisions.

I fear as a community we are still underskilled, underprepared for the future: for embracing uncertainty and identifying with the future.

And so, as we celebrate, look back and learn from the last 40 years, Talking Infrastructure plans to act like the future matters.

Starting with a time series of blogs to ring in the New Year. Your contributions most welcome!

In April 2024, it will be 40 years since Penny Burns started the whole thing. Talking Infrastructure plans to party like it’s 2024, all year.

2024 also marks milestones for the Global Forum for Maintenance and Asset Management (update of the AM Landscape), ISO (10 years since ISO 55000), and the Institute of Asset Management (30 years since it was founded): there will be a lot happening.

The need for more considered decision making for our future infrastructure has only grown and become more urgent. Asset Managers everywhere know this. Our 40 year celebration will be an opportunity to take this message not only to managers of infrastructure but also to those who decide, design, construct, fund and vote for our infrastructure.

Like infrastructure itself, our purpose is to support the wider community. There is a lot of satisfaction to be had in this and we invite you to join us, and enjoy it too. What area of Asset Management and decision making particularly interests you?

We are looking to develop a circle of advisors, who, through their interests and work, can have the fun of keeping Talking infrastructure up to date with current issues, and setting its future directions.

Your ideas for celebrating our 40th are also needed and much welcomed. This will include events across Australia in April, and presence at AM conferences and articles wherever and whenever we can.

What did we learn in the last forty years? Where do we need to go in the next 40 years?

Recent Comments