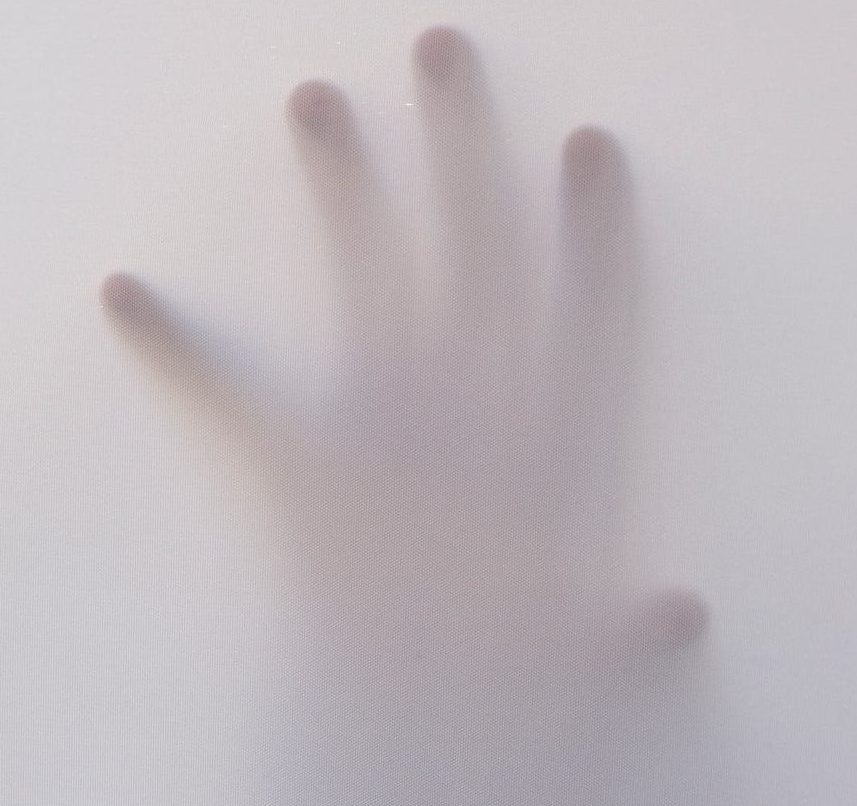

How can you plan for the unknown – when you literally cannot see your own hand in front of your face? Well, back 12 years ago, when she headed up the Strategic Asset Management Team at RailCorp (now Sydney Trains) I facilitated a scenario planning exercise for Ruth Wallsgrove. The scenario we looked at was an epidemic with an immediate impact on ridership, with everyone – although, of course, we didn’t call it that – ‘social distancing’. Now over to Ruth to look at the implications that has for us today. PB.

The importance of planning

“Emergencies are overrated as a response mechanism. Are preparation, prevention, and planning about to become more popular alternatives? Can we nudge this? “

Planning – that is, thinking ahead and co-ordinating what we are going to do – appears to be central to dealing with Covid-19. We do not know for certain what the conclusions will be, except that South Korea seems to be doing well, and the USA not.

The nature of planning

I teach AM to a lot of people, and quite a lot of them ask how you can plan when you don’t know exactly what’s going to happen. The answer is, of course, that it is even more important to plan when you don’t know exactly what will happen. The point is to give yourself a framework for flexibility. No planning ahead at all gives you nothing to work with.

It would not have been a sensible plan to stockpile ventilators. And there was no possibility to stockpile Covid-19 test kits, because they didn’t exist. Good planning instead would be putting in place the thinking processes that would enable us quickly to ramp up production of known equipment, and to come up with new tests and vaccines.

Scenario Planning

Scenario planning seems to me to be the opposite of Planning with a capital P: the opposite of a high up committee coming up with a visionary Plan for transforming our infrastructure.

The idea of scenario planning is to look at alternative scenarios, and ask what the data tells us. It’s to consider what to do if the future doesn’t go the direction you want it to. What you can influence. How you can stay nimble to respond to what reality tells you.

The Chain of Consequences

In our scenario planning session in 2008 we were asked to consider – Could an epidemic lead to an increasein ridership?

Trains and buses are currently empty not just because people don’t want to be in a small space with many other people, but because many of us are in lockdown. Our workplaces have closed and, if we are lucky, we are working from home. (If we are not… we are out of our paying job, temporarily or permanently).

What if: people go on being nervous about crowded spaces after we go back to whatever the new normal is?

Well, one possibility is that everyone heads to their cars with a vengeance. But what if that led to impossible traffic jams, as most cities already had no spare capacity for personal vehicles?

What if: someone comes up with a neat way to avoid breathing germs on each other? This was one of our scenarios. How could the chain of consequences lead to an increase in ridership? It’s not even hard to do, once you free yourself from thinking you ‘know’ what people will do, or should do, in future.

Along with scenario planning, we also need the skills to go beyond the immediate, and ask what the knock-on impact of one event on another. Such as the basics of AM: if I build this rail line, what will that mean for operating expenditure for the next thirty years? What does it mean I can’t do, because I’ve dedicated resources to this rail line instead of that arts centre? What are possible impacts on our overall capabilities – including the environment? (There is always another Plan, but no Planet B…)

The role of Asset Management practitioners

In late 2018, when a wire down led to a wildfire that burned down a town in California, much attention was paid to control the spread and mitigate the fallout. The AM team were involved, however, not in initiatives to look at the urgent immediate risk, but rather in the important task of what to put in place to reduce such risks in the future. So often, as we know, the urgent drives out the important.

We are not emergency planners; that’s an honourable discipline in its own right. Our job is to consider scenarios and chains of consequences (“and then what?”) and building flexibility into our asset systems and our processes.

Recent Comments