From script by Lou Cripps

Infrastructure schemes tend to suffer from optimism bias: assuming everything will work as planned.

Focusing on benefits and forgetting some costs is one reason infrastructure projects tend not to be as good as their business cases.

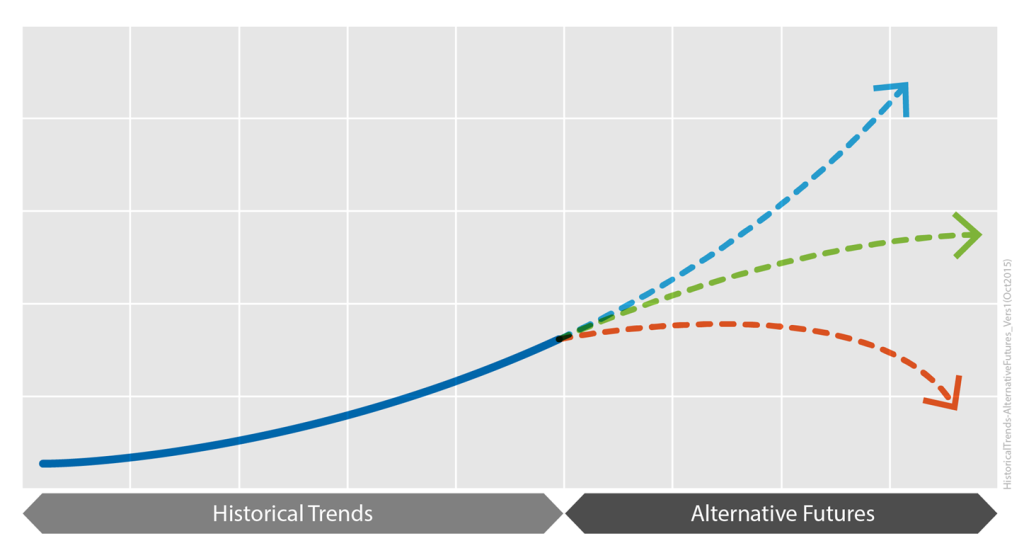

But there’s a parallel problem with risk and time.

Hofstadter’s Law: It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.*

The UK TV programme Grand Designs comes to mind in relation to projects. It doesn’t seem to matter how many years the programme has been running, or the presumption that people who appear on it will have actually watched previous episodes.

In ambitious projects for houses, there seems to be a McCloud Law at work. People will always plan to be in by Christmas, unless they are expecting a baby (in which case they want to be in just before it is born).

In the UK, that means they are probably rushing to weatherproof the house in November, so they can get to work on the interior. And this in turn means they are invariably dependent on it not raining until the roof and windows are installed.

So the question is, is it likely to rain in the UK in November?

There is a technical corollary to this: that the glass for the windows will be delivered late, in any case. Apparently all builders know this.

*Coined by Douglas Hofstadter in his book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (1979). McCloud after Grand Designs’ presenter Kevin McCloud.

One of my great pleasures in life is to sit in a café and talk infrastructure. A popular topic, even before Lou Cripps came up with the idea Asset Managers are platypuses, is what makes an effective one? Or even what attracts us in the first place.

Who are ‘our people’?

To defend us from accusations of exclusivity, I need to point out that it’s not about what you studied at university, or which country you grew up in. Good Asset Managers are ‘anywheres’, as Ark Wingrove put it.

This is, of course, a Serious Subject, as we desperately seek to switch to a future-friendly mindset; seeing the bigger, longer picture around physical assets. But it’s also kinda fun to think about the difference that makes a difference.

Like the AM team who came on one of my courses and took me literally. We teach whole life costs, cost-risk optimisation, thinking in risk, and how information is all about decision-making. But I don’t think most attendees go away and start actually doing any of that. This team did.

One reason people don’t try whole life cost modelling, or risks in $, is because they think it’s too hard before they even start.

But my best students – well, if that was how you do Asset Management, they would figure out how to do it. When I later asked Todd Sheperd how they quantified asset risk, he said he looked it up on the internet. After reading a recommended book and going on a recommended course. (As I said, he took me literally.)

Yes, he must have had the confidence to believe he and his team could figure it out. But I think it’s more than that. It’s about curiosity and openness to learning.

It also involves a belief that if I don’t know something, someone else may have worked it out, maybe in a completely different context. We can learn from others – like 17th century gambling mathematicians, or stock markets traders.

Or actuaries. It’s as if 99% of attendees on AM courses have never heard there is a whole profession who have worked out how to put $ on risks.

Sitting in a café recently with Todd and Julie DeYoung talking about infrastructure, we also recognised another quality: interest in what we can learn from people doing something that’s not exactly the same as what we’re trying to do. Like wondering what we can learn from assets that aren’t exactly what we have – instead of deciding ‘our’ assets are so special there is nothing we can learn from others (and the processes of AM planning and modelling don’t apply to us).

In other cafés years ago with another old AM friend, Christine Ashton, we thought it’s about pattern matching. About looking at a problem we had, and the kind of technology approach it needed, as opposed to a fixation on a particular software tool, for example. What kind of problem is it? What sort of tool could help?

To me that’s linked to 80:20 thinking, but I suspect that some of my best AM buddies are better at details than me. It’s happily straying into the unknown, instead of trying to force everything to fit into what you already know.

I love (nearly) all of my students, of course. But not all of them turn out to be my sort of café people.

Shout out to yet another recent café and Janel Ulrich – her of the ‘can we develop our SAMP in the next 12 hours?’ (yes, of course we can). I love the way she loves ‘our kind of people’, in all our quirks and heartaches and irrepressible openness.

Others who will recognise their café contributions include John Lavan and Manjit Bains. And Penny, with whom too many of these café conversations have to be virtual.

Thanks to my brother Bill Wallsgrove

Board member Lou Cripps and his team at RTD are great Asset Management practitioners – and that is largely because of their attitude to time.

For example, the team prepares carefully for meetings with key stakeholders, not just the CEO but engineers, IT, maintenance, HR. They think carefully about what they want to effect through the meeting – their objectives – and then project forward what the possible response/s of the others will be, based on their previous interactions. They can then work on what will most connect and make a win:win outcome likely.

Lou’s team also makes full use of red-teaming and pre-mortems, to imagine what could go wrong with an initiative so they can prepare not to go there. Risk assessments and risk plans, essentially, but exploiting the human ability to project forward and then ‘look back’ in our minds. (“Imagine it’s six months’ time and we are doing a post-mortem on what went wrong.”)

Lou refers often to ‘future me’ and ‘future us’: that is, stepping in the shoes of himself in a year or ten years’ time. This is not just to feel how fed up he might be then about what he failed to do now, but also to consider what future him would care about more widely. It is empathy with a future self. And it does not even need to be yourself. What about someone in the community in a hundred years?

This is good Asset Management for infrastructure, in particular, as infrastructure decisions we make now should always be assumed to have lasting implications. The assets we build now may still be in use in a hundred years. And the things we don’t build because we’re building something else. The lost opportunities, and future debts. What we fail to maintain, so will have to be built again…

Lou’s team last year relentlessly analysed the data to work out the likely costs – the total costs, now and into the future – for a proposed project to buy more electric buses. They worked out that this particular set-up would cost their transit agency approximately $2 a mile extra on every electric route for the next 50 years. It wouldn’t even save on carbon, because the electricity supply proposed was fossil fuel burning generation. (It was not a good proposal, and the Board duly turned it down thanks to their analysis.)

To build and not think ahead is a dereliction of duty. Principle number one for an Asset Manager: always ask, “And then what?”

Making full use of the past, in order to think ourselves into the future.

How do you this in your team?

In 2024, Asset Management turns forty.

One key question for me this year as an Asset Management practitioner is time itself, and how we act with the future in mind.

The innovation of Asset Management is very largely about time. Penny Burns created AM to look forward in time and consciously choose whether we needed to renew like-for-like, or should manage our assets differently in future.

Forty years ago, we were not thinking about climate catastrophe, and we were only just at the start of the IT revolution. (I had only just seen my first PC, and the world wide web, smart phones and terabytes of data storage for $50 were barely pipedreams.)

But the question of longer-term thinking has in some ways gone backwards in our societies since then, not forwards.

The vast majority of infrastructure organisations still only have very short term asset plans, and almost no asset strategy. More have, must have, 3- or 5-year plans now, thanks to AM as much as anything. But the 15 to 20 years plus strategic view that Penny proposed is still a challenge.

And shockingly few agencies even use life cycle modelling to project the very basic realities about the timings for replacements, let alone a mindset of always asking ‘And then what?’ of our day to day and year to year asset decisions.

I fear as a community we are still underskilled, underprepared for the future: for embracing uncertainty and identifying with the future.

And so, as we celebrate, look back and learn from the last 40 years, Talking Infrastructure plans to act like the future matters.

Starting with a time series of blogs to ring in the New Year. Your contributions most welcome!

In February, I posted a request for input on what skills, experiences, aptitude we need to be an effective Asset Management practitioner.

I have been looking at this for a review of the IAM Competences Framework that’s about to kick off in earnest next week. But I’ve been thinking about it since I did a spreadsheet for the previous IAM professional development chair, of everything a well-rounded AM practitioner needs to know about – and therefore, maybe, what to teach them on an advanced qualification course such as the IAM Diploma..

But, this being Asset Management, this is made more complicated by ambiguities.

Who is an Asset Manager: someone in a team called Asset Management, or everybody involved with managing physical assets? What about an Asset Management consultant? What is more like general knowledge that we should be aware of, maybe speak the language (of finance, say) without actually necessarily being able to do it?

‘Everyone involved’ covers a huge range of competencies, including all the technical disciplines and specific lifecycle skills such as design, project management, maintenance. An AM consultant may need to be a specialist in something specific rather than a generalist in order to be saleable. Knowing enough about finance may be about knowing what wikis to look up for terminology.

So I have tended to go with the question of the core capabilities of a dedicated AM team inside an asset owning organisation – and increasingly, what they need to know that they wouldn’t get coming through the ranks of maintenance, or in an engineering degree.

There is understanding about the business of the organisation. There are soft, people skills such as communication and facilitation. Some of this can be taught on training courses.

But two interlinked areas that currently trouble me are risk and information.

I have sort of realised these are a problem for a while: how many of us have no real sense of information, and I don’t mean IT here; and what (high) proportion of us didn’t like statistics and probability in our degrees.

People are far, far more likely to ask questions of potential hires about their engineering backgrounds – or even test their Excel skills – than their usable skills with risk and information analysis.

And yet I recently had reason to think that most of us are not up to speed with the 17th century on using risk. With the 17th century gambler-mathematicians who laid all the groundwork for risk-based decision-making, for decisions where we don’t know exactly what is going to happen because it’s in the future, which is basically all decisions.

And that the AM people I know who really use information well come are ex-military intelligence, or teach data science, or have highly educated librarian backgrounds. In other words, really high-grade information skills. Many of the rest of us seem to be floundering.

Asset management capabilities are not only not primarily engineering – what if there are major disciplines which we need, but fail even to reach for serious education on?

What does perfect Asset Management look like? What’s at the top of the mountain we’re climbing?

And what’s a metaphor between friends?

But to some of us it’s more a windy, winding road, over yet more hills, where we sometimes see part of the road up ahead, but never glimpse the end.

Why does this matter? Having recently faced a virtual room full of people saying they would know what to do next, if only someone could describe the end state for them: as though Asset Management is an accomplishment, something you can complete. Done, checklist all checked, and move on?

In contrast, is there a destination for, say, engineering? Although many engineers may not examine what they believe, they surely think of engineering more as a state of mind, a way of thinking, rather than something that gets finished. (And who even has a vision of HR?)

We could describe the top of our mountain as the point where everyone takes it for granted that we think longer term, whole system and lifecycle, use information wisely, and truly embrace uncertainty.

But I don’t think that’s what the metaphor betrays. I think it’s more ‘when we have a complete asset inventory and a strategy for every class’ and can stop thinking about them and move onto something more fun. The way some, at least, appear to think a check the box approach to ISO 55000 is what we need, or even the point.

But, you know, it’s also whether fun to us means continual discovery, the thrill of not knowing and then learning – or getting back to my desk to fill something in.

Roll on, rolling road!

My boss has been heard to say that when they started the company in 1997, he assumed that within a few years we would have figured everything all out and would just be applying the Asset Management manual. Instead, we learn something new on every project… Twenty five years on, that’s certainly true for me.

My old colleague John Lavan described what we have to do as tackling problems, not solving puzzles.

A puzzle is (in his terms) something where you already know what you have to do to solve it. It’s a rule-based game, like school-level mathematics. Apply this methodology and it will come out right.

Whereas we are faced with problems, where we don’t necessarily know what to do, or if there is a good solution.

As soon as we work out a useful approach on something, we’re faced with having to evolve it further. That is, even if we’re lucky enough to have a good way to start.

Fellow Talking Infrastructure Board member Lou takes this further. There are puzzles, which don’t resemble Asset Management, but perhaps some engineers still wish for; problems, which seems to be our AM world; and predicaments, where there maybe isn’t a solution at all.

I’d like to think building an asset inventory is a puzzle that we already know how to solve. Plenty of individuals don’t yet know, of course, but that feels like just an issue of communication.

On the other hand, what’s an effective strategy for Asset Management in a particular organization? We know the principles (alignment to corporate targets, the Six Box Model of elements), but that’s merely the opening tool kit. Making Asset Management business as usual is a problem, still, for just about everyone. Too many variables and different nuances.

Old age is a predicament. And as for climate change? Maybe, given human psychology, it’s a predicament, not simply a problem.

“What’s the first step to a good Strategic Asset Management Plan (SAMP)? A bad SAMP…”

My ex-colleague Ark Wingrove’s saying has resonated with clients since he first coined it. You do not have to wait for perfection; the important thing is to start, knowing you can improve as you go.

It works not just because it’s true. Just having someone tell you you won’t get everything in Asset Management perfect first time liberates us to try. Otherwise – and this surely tells us something about the asset culture we pick up, and need to change – we get frozen in the headlights of needing to be right.

It’s a profound truth of AM that you will never know enough about the future; and yet you still have to have a strategy, you still have to plan, you still have to make decisions that matter. And so inevitably we will get some important things wrong.

The approach that the AM documents and processes we produce are all iterative is, of course, built into the diagrams, the 6 Box Model and the flow of ISO 55000, continuous improvement and the ’learning loop’ of Plan-Do-Check-Adapt. The idea that, above all, we can’t leap straight from muddle to highly sophisticated Asset Management Planning has long been recognised in Australasia. We have to build, step by step, our planning evolving with our increasing understanding.

But it just struck me that it’s not simply how we improve things as we know more. The real blocks are thinking we know more than we do at the start, and the fear that we will be exposed for not knowing enough – the toxic aspects of being an expert.

Years ago Penny Burns came in to take my Sydney team through scenario planning. The real achievement of this was to move everyone away from their confidence. From believing they could ever be certain about the future.

In an exercise around understanding our levels of uncertainty in risk training this week, someone asked – tongue in cheek – how we could ‘win’.*

The urge to be right is natural, I guess, but it also goes with all sorts of baggage. That we won’t even start unless we can be certain. That it is better not to try than to run the risk of being wrong.

As though, for example, a strategy for Asset Management is a test we have to pass.

The principle of evolving, getting better as we go but never reaching 100% certainty. What examples of positively ‘embracing uncertainty’ have you seen in practice?

*Calibration training based partly on the work of Douglas Hubbard, see his The Failure of Risk Management. If you have never come across this, aiming to show off that you’re right that will ensure you don’t get it right. (And even telling people this doesn’t help them, at least the first time around.)

I’ve long been fascinated by the idea that we need ‘bridges’: people who can translate between two domains with different mindsets.

One key gap to bridge is between science and management, as Penny describes https://talkinginfrastructure.com/2022/07/20/science-and-asset-management/ . There are other gaps that affect us in asset decision-making.

In the late 1990s two of us, now very senior IT director Christine Ashton and me, put forward the need for such active translation between IT and business users. IT has always struggled to understand what’s really needed by users, as the users themselves are poor at describing their information and information processing requirements.

Christine and I set up a special interest group in the British Computer Society – an organisation which could do with some translation in the first place – for people who work between IT and business. We had a great time discovering some very good people, who, I am happy to say, generally earned pretty good remuneration for their ability to understand what the users need and turn it into something IT techies could understand (and use). It’s still a rare and precious ability.

And it’s surely still as big a challenge as ever.

Add to that how to bridge between an engineering mindset and business. I train engineers who still radiate – why do I care what the objectives of the organisation are? My job is to do the right thing by the asset, regardless of management.

It’s fascinating in all three cases, because scientists, just like engineers and IT in their different ways, are kinda proud of their ability not to compromise with business and organisational realities.

In particular, the issue of ’embracing’ uncertainty is just so relevant to Asset Management. But we educate scientists, engineers and IT to hanker after 10 decimal places of clarity.

And, I fear, not to ask ‘so what? – or, what happens next?’ as often as they should.

Recent Comments