Image from James Webb Telescope: Interacting Galaxies

After taking three months off – impressed how much surgery slowed me down! – I am taking stock.

I find I am almost totally not interested in Asset Management as a technical subject. Or rather, that I have no hope that something technical (like ‘AI’) will sort it for us.

And yet, there is still a large problem to be sorted, that surely requires new, and clever, thinking.

The Talking Infrastructure board is more or less convinced that we have not yet made Asset Management stick. In particular, to get where Penny saw 40 years ago: business as usual longer term planning to meet infrastructure demand. And more recently, planning ahead in a changing world.

One painful example is the retreat from meaningful AMPs in Australian councils, their first home.

Why infrastructure organisations don’t face the future has been a puzzle. Vested interests, for example in the construction industry, sure; lack of skill or vision in the decision-makers, yeah. Is it basically that the pain of not planning adequately doesn’t fall on the people failing to plan?

Our inability as a species to think beyond a few years?

But I am not yet that pessimistic. I don’t believe it’s biological.

What most grips me is the problem of culture. Yes, we happen to live in a peculiarly short-termist culture. But let’s, as clever people, tackle it as a Meadows-type system challenge.

In the past decade some of us have asked how we can get an organisation to plan sustainably: to have a process, a system to plan out our assets, that outlives any CEO, or any individual asset manager for that matter. A few years ago, a network of us in North America looked at how to ensure that an incoming CEO took an AMP process as given. Useful and entrenched enough not to be their focus for change.

Did we succeed anywhere?

Watch this space…

At least the pet duck enjoyed it

When we moved into our house, we first realised the problem when the mortgage company said we needed flood insurance, and discovered that would cost ten times the normal building and contents policy.

Until a smarter insurance company here sold us a cheaper policy based on postcode (in other words, by group of two or three houses), not Environment Agency flood areas: they spotted a market opportunity for a more precise risk assessment. Smug us!

Until six years later, and the house actually did flood.

And four years on, in late 2024, the water came to our front door twice, and overtopped the sand bags the second time.

And the risk of flooding in England is predicted to increase five-fold in the next decades under current projections for global warming.

However, Newport Pagnell is not Miami.

To be clear, our flooding is due to rain, and living next to where two rivers meet. Unfortunate timing of river surges – or someone getting the timing off on floodgates. We are nowhere near the sea and don’t get hurricanes, and so far the extent of our flooding is a few inches of water at the front of the house.

A few houses flooding a bit: you start thinking about resale values, and whether getting wet every year or so will do the brick walls and wood floorboards any good.

In South Florida, they face losing whole towns to the sea and the swamps. Many people live only a few feet above current sea levels, and the infrastructure is similarly low and at risk. They have to worry about overwhelmed sewerage systems and nuclear power plants.

Florida has such a tax-averse politics that it will come down to money for school education versus money for flood action soon for some towns. They continue to build right up to the sea and in areas only just above sea level, even as they watch the hurricanes track towards them. And of course the ruling Republicans also mostly deny climate change.

It would seem a perfect storm of human inability to face the facts.

But it is striking just how much of an issue it is for infrastructure. And that involves use of tax dollars, national insurance schemes, building codes, politics and Politics: so much more than simply technical questions.

Do we speak the right language/s to manage this?

Among my personal highs and lows of 2024, the standout experience was going to Japan.

I am sorry to say I have never encountered a Japanese Asset Manager, but thanks to GFMAM I got to hear a rep from the Japanese maintenance societies at the IAM UK conference in London last month.

Despite what we hear about its economy, the country is still doing very well on total maintenance and quality in manufacturing. Some days it seems every other car on our roads is a Toyota.

And my overriding sense of Japan? That along with the incredible food and gardens and manufacturing, it’s simply the most sensible society I have ever seen.

Starting with the toilets at Tokyo airport when we arrived.

I have long suspected the most important thing about Asset Management is that it is sensible. Don’t spend where you don’t need to, but do what you must to sustain what we need to thrive. Don’t preach growth for its own sake, and be wary of ‘innovation’ (think of ‘the Maintainers’ and their 2020 book The Innovation Delusion*). What does the evidence tell us? What risks are we really running with our assets? Cut through the lobbying and classical economics – and make sensible decisions.

Sensible is not necessarily glamorous; AM is not glamorous. It doesn’t pander to fantasies, of engineering or entrepreneurs.

As several Western countries seem to lose the plot, even caught up in what can only be described as fascist dreams, it was wonderful to experience somewhere that has a much stronger sense of its limits. A lot of people in a limited space, and some of that physical space quite dodgy: how can we organise food, rub along with millions of strangers without pulling guns on each other, love nature (trees!), create beautiful things? Value education, and don’t take our gods too seriously.

Take what we need, and reject what we don’t.

Yes, I am hopelessly romantic about Japan, ever since my father worked there when I was a child. But I didn’t expect to come away with sensible.

PS not sure I will ever be happy with cold toilet seats again.

* The Innovation Delusion: How Our Obsession with the New Has Disrupted the Work That Matters Most

Note: Japan, like many countries including the UK, USA, China and France, not to mention Germany and Russia, has some dismal history. Unlike some of those countries, it appears to be able to learn from its past, but this is not to excuse its treatment of Korea and China and prisoners of war in the past.

My team makes use of premortem thinking: as part of planning action, immediate or long term, consider how it might go wrong. We think ourselves into the future looking back at a project (or a meeting). Humans are surprisingly good at this time-travelling.

For me, this is part of a principle Asset Managers should embrace: the principle of reversibility. It’s not just about understanding the consequences of our decisions, but also about planning for the ability to undo or reverse their effects if needed. Sure, you can’t un-ring a bell, but we can find ways to get as close as possible to the pre-action state and minimize the impact if we think about it right from the start.

Do our plans have exit strategies or an undo button? None that I have seen, why not?

This is especially crucial in infrastructure projects, where large investments and long lifespans magnify the potential impacts. How would they be delivered differently if that was required? Would that requirement cause us to better maintain the infrastructure we currently have? I think so.

Let’s face the hard questions: Can we put rare earth metals back in the ground? Can we undo the energy consumed in building something new?

By embracing the principle in Asset Management and infrastructure decision-making, we can strive for resilient and adaptive systems that serve the present while safeguarding the future of generations to come. We navigate challenges with eyes wide open.

We ask tough questions, anticipate consequences, and face the answers with truth – and then we create our plans and strategies.

If you are planning to attend our Sydney celebration, please RSVP to: amis40@talkinginfrastructure.com so we can keep an eye on numbers – limited to the first 60! Event is free, includes food and discussion with Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda and a whole heap of old friends and colleagues.

Full update of the 40th year celebration events shortly!

Join us at the Harbour View Hotel in the Rocks and help celebrate with finger food and drinks – plus Penny and Jeff on what we have learnt from the last 40 years to help us meet the challenges of the next 40.

Many thanks to Richard Edwards, Lynn Furniss and Matt Miles of AMCL

Penny Burns and Talking Infrastructure will be on the move in April to celebrate 40 years of Asset Management, and look forward to the next 40.

Adelaide April 15 & 16, Penny and Ruth will be celebrating at AM Peak.

Brisbane events April 17-19

Sydney April 24, venue TBC: Asset Valuation in a time of Climate Crisis. Including Jeff Roorda on how Blue Mountains City Council is taking a radically new approach, as well as Penny on how we must rethink our AMP modelling.

Melbourne April 30, IPWC. Penny speaking on the opening morning of IPWEA conference

Wellington May 4-6, events to be announced

Let us know if you are interested in meeting up in any of these cities.

See you in April! #AMis40

© https://www.dreamstime.com/ image120059878

I love a friendly alien. Some of us – possibly the less military minded – have long preferred stories of good contact experiences, from ET and Close Encounters of the Third Kind to Arrivals. Indeed, the grandmammy of them all, The Day the Earth Stood Still, which is about the shortcomings of militarism.

There’s a new generation of sci-fi with what can only be described as positively cuddly species from other planets. The close encounter in A Half-Built Garden, by Ruthanna Emrys, echoes The Day the Earth Stood Still in that the aliens have come to save humanity from itself. But the ‘dandelion networks’ are already saving the planet through direct democracy based around watersheds, to them the natural way to organise.

And it could not be more cuddly: the first human to meet the aliens is woken by water pollution alarms in the Chesapeake in the middle of the night, and hurries out to check what is happening taking her baby with her. Turns out the aliens don’t trust anyone who would not bring their babies to a key negotiation.

The principle the dandelion networks use in decision-making about infrastructure and other technology is: will what we are building be at least as benign as a cherry tree? With evident, multiple benefits and few costs, and a net positive impact on the environment?*

If not, don’t build it.

Is there anything we are building today that would pass the cherry tree challenge?

*Ruthanna borrowed the metaphor from Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things by William McDonagh and Michael Braungart, 2009.

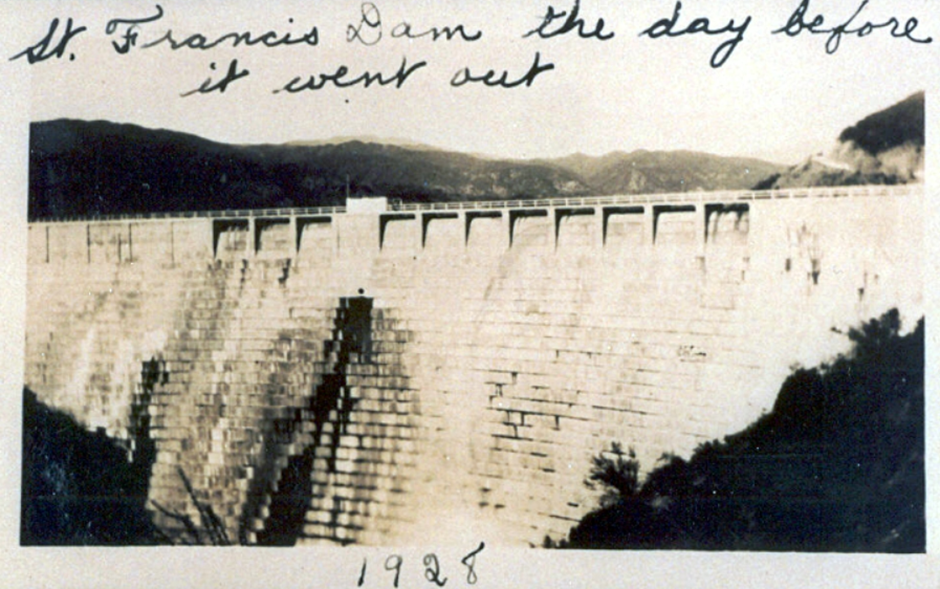

Last known photo of St Francis Dam before it collapsed, © scvhistory.com

You know when you hear something you never noticed before, and then hear about it again the very next day? (It’s known as the Mandela Effect.)

I mean, I saw Chinatown many years ago and so understood that there was a rotten heart to Los Angeles’ water supply, but I never thought about where the water comes from – or understood how it trashed a valley and its communities in the 1920s.

Originally called Payahǖǖnadǖ, meaning ‘place of flowing water’, Owens Valley is a now dry valley north of LA.

I work with enough hydro dams to be curious about dam failures – there have been a few catastrophic failures in the 20th century – so wanted to watch a PBS documentary about the total failure of St Francis Dam in the valley. It failed because of hubris. It did not make it past its first day in operation. But the documentary was about much more than the immediate collapse and the hundreds of people who died that day.

Los Angeles basically stole the water, buying up water rights surreptitiously and sometimes illegally. For some reason I can’t comprehend, it even memorialises the engineer responsible for the dam failure (and the overall aqueduct, which does still exist): Mulholland, of the Drive.

And the day after I watched the documentary, I read a review of a book titled Dust, by Jay Owens, using the Owens Valley as a 20th century example of humanity creating arid dust bowls where there were once thriving ecologies.

Metropolitan LA is a funny old place. I have spent plenty of time there as my brother moved to Azusa in the late 1970s, and retired to Orange County to the south. It was hailed as the city of the future once, but water is the big question mark, still. You would have to conclude that the LA basin is well beyond its carrying capacity, and perhaps always was.

Owens Valley, and St Francis Dam, seem suitable reminders of the challenge of sustainability. enshrined in the original BSI PAS 55 definition of Asset Management. The valley and its people – original and immigrant – paid the price for the development of a vast city region.

Not the first and surely not the last example, but a sobering reminder that water engineering is both hard, and not always on the side of the angels.

Photo 63254580 © Liliia Epifanova | Dreamstime.com

2023: surely the year for harder questions about the impact of our infrastructure on biodiversity.

For example, researchers in Idaho built a fake road to test out the impact of freeway noise on migrating birds.

“A third of the usual birds stayed away… those that stayed paid a price,” writes Ed Yong in his fabulous book Immense World on animal senses. The noises drowned out the sounds of their predators, so the birds had to spend more time looking for danger and less for food, so they put on less weight and were weaker for their migrations – which take every bit of energy the birds have.

And this didn’t include actual road effects from headlights, exhaust fumes, polluting run-off.

As Ed Yong says, more than 83% of continental USA lies within a kilometre of a road. There is nowhere else for the birds to go.

We have options to do something about this in our infrastructure, in a year we’re meant to be ‘building back better’.

Just replacing blue or white LEDS with red in, for example, parking lot lighting cuts down the impact of night light on insects. Sound-absorbing surfaces and barriers; slowing down traffic; quieter vehicles – all can immediately reduce noise pollution for animals such as owls and mice who depend on sound to catch or avoid being caught.

If 80% of humanity live under light-polluted skies and two-thirds of Europeans live in the noise equivalent of constant rain, it’s not great for people. But what Ed Yong brings out so brilliantly is how often we don’t even think about the different and miraculous sense worlds of other species, of whales and manatees and frogs and birds, and how very much worse it can be for them.

Is this the year to start taking seriously a problem we’ve only just begun to realise?

Immense World, Ed Young, 2022 – how other animals sense is truly mind-blowing.

Recent Comments