Thinking about Waves 3 and 4 of Asset Management, this quote from a recent novel struck me:

“It is difficult for anyone born and raised in human infrastructure to truly internalize the fact that your view of the world is backward.

“Even if you fully know that you live in a natural world that existed before you and will continue long after, even if you know that the wilderness is the default state of things, and that nature is not something that only happens in carefully curated enclaves between towns, something that pops up in empty spaces if you ignore them for a while, even if you spend your whole life believing yourself to be deeply in touch with the ebb and flow, the cycle, the ecosystem as it actually is, you will still have trouble picturing an untouched world.

“You will still struggle to understand that human constructs are carved out and overlaid, that these are the places that are the in-between, not the other way around.”

– Becky Chambers, A Psalm for the Wild-Built (Monk & Robot Book 1), 2021

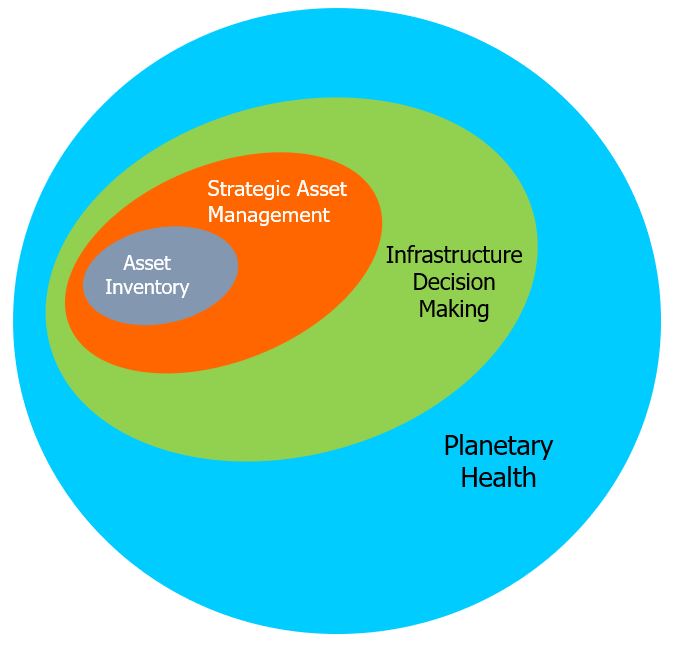

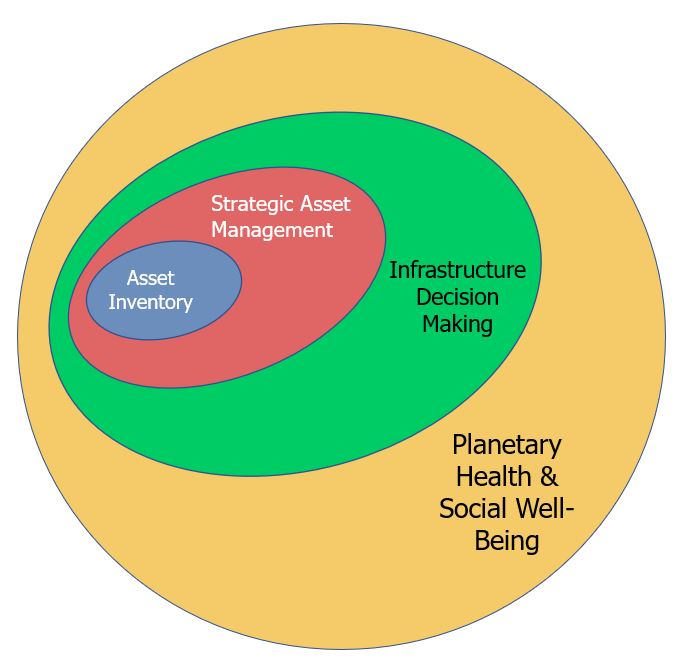

In a previous post, there was a diagram showed how each of our ‘waves’ could also be conceived of as particles, embedding and building on each other. .This is our latest version, to capture the ideas of ‘grey assets’, as opposed to green and blue assets.

For the last 40 years the economic focus has been on growth.

And so infrastructure decisions have also focused on growth. But now this growth focus is changing as we realise the damage we are causing – and so asset management and infrastructure decision making needs to change, too.

We are now at a pivot point.

We have been at pivot points before. This is what Talking Infrastructure’s THE ASSET MANAGEMENT STORY is now documenting.

At each pivot point in Asset Management (the beginning of each wave), we have expanded our understanding of the world we operate in. Starting from simply maintaining and recording in Wave 1, we moved, in Wave 2 or Strategic Asset Management, to using this information to optimise decisions concerning our existing portfolios.

Then, in Wave 3, we look to take on a bigger role, infrastructure decision making, where we go out into our communities to work on whether the size and shape of our portfolio is what it needs to be. Wave 4 extends our understanding of our asset portfolios to the impact we are having on society and planetary health, and actively seeks to improve these impacts. The task in Wave 4 is to make all infrastructure decisions ‘future friendly’.

Wave 4 is the challenge that Talking Infrastructure was surely set up to address.

It is our most critical pivot point yet in asset management. This is the challenge that Talking Infrastructure CEO, Jeff Roorda, is leading at the Blue Mountains City Council where he is Director of Economy, Place and Infrastructure services. The city’s focus is on Planetary Health and Social Wellbeing. And we will be reporting what the City, and others with whom it is working, learns so that everyone can move in a saner direction than we may have done in the past.

If this interests you, watch this space, for a new series of blogs about infrastruture and biodiversity.

And, of course, become an active part of the dialogue on Talking Infrastructure.

In May 2018, Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda wrote here about three ‘revolutions’ in Asset Management – later renamed ‘waves’, because that captures better the idea that one wave doesn’t supersede another.

Since then, we have discussed with each other and many others how Wave 1, ‘Asset Inventory’, is more successful if you already have in mind the vision of Wave 2, ‘Strategic Asset Management’ and how you are going to use all of the information you collect.

We have looked at what Asset Management practitioners need to develop to move on from this, to be able to look beyond our own organisations, to a bigger role in supporting our communities. We called this Wave 3, supporting better ‘Infrastructure Decision Making’.

We have even begun to imagine Wave 4.

As Penny puts it: whereas Wave 1 looked at WHAT we had, and Wave 2 looked at HOW we needed to manage it, Wave 3 started to ask WHO we were serving by our efforts. This has brought us now to start thinking more deeply about this question and about the next move, looking at the critical question of WHY.

As Asset Management practitioners, we have to ensure we are in the right positions of influence to be able to challenge existing infrastructure assumptions, which is what I think Wave 3 is all about. To look ‘up and out’, as Lou Cripps of RTD puts it.

But we can already spot that there is no point in being able to ask hard questions, if we don’t have the right questions to ask….

What do we mean by ‘better’?

Dreamstime.com/ 187958062 © Meg Forbes

The world of infrastructure Asset Management has had the benefit of an evolutionary model for several years: the ‘Waves’ of Penny Burns, to make sense of how organisations seem to have to go through a period of focus on basic information (Wave 1, Asset Inventory) before they really look at how to use it to make better decisions, to start optimising (Wave 2, Strategic Asset Management).

Before that, I confess, I struggled to express what was going on: how could people get stuck in data and databases? I don’t know that I fully understand, still, but I least I recognise it now – that having a list of all your assets, simple facts like install date and location, and a big dumb database to put it all in preoccupied so many of us for so long.

Penny herself seems not to have spent too much time worrying about this, but always had a vision way beyond it. She assumed we would have a grip on lifecycle costs, thinking longer term, and planning ahead, and get down to acting smarter on our asset decisions.

And now, as we work together to capture our collective history and development, we are really looking forward to the next Wave. To really so much better infrastructure decision making that is fit for purpose, through the rest of this turbulent century.

Look out for celebrating our history on July 29th!

Dreamstime.com/ 191317844 © Lefteris Papaulakis

It’s always an interesting question: why do things arise when and where they do? Why Asset Management in Australia in the 1980s, when plenty of other useful asset ideas came from other places and times – reliability engineering in US commercial airlines post-war, for instance?

And when I explain where much best practice comes from, why is New Zealand such a paragon? There are very good reasons, when you ask about the when and the where.

There is something about fundamental ideas that makes understanding the specifics important. An approach that seems like such a good idea as Asset Management – why wasn’t it more obvious, earlier, to more people? A fabulous clue as to how what seems like an obviously sensible mindset, required something major to shift. A chink in older assumptions, even culture, that let someone, something start to question, to let a new light in.

I suspect a lot of us struggle about why people resist what seems backed by logic, evidence and good sense. But I don’t want us to go down the deep, dangerous rabbit hole that is conventional economics, making a simplifying assumption that people are ‘rational’ the way they define it – a definition which doesn’t really care why people do what they do, or how what seems ‘obvious’ in one situation doesn’t work in another, or anywhere.

And that is partly why I love physical infrastructure. One size really doesn’t fit all* – a good strategy for one kind of asset would be barking wrong for another, and even for an identical asset in a different context. And it all depends on what you are trying to achieve, specifically.

Physical assets are the opposite of idealised generalisations. Yes, there are generally good questions; but not universal good answers, at least not in my experience.

Infrastructure Asset Management is the epitome of the full appreciation of time and place.

Watch here for the publication of the first part of Penny Burns’ history of Asset Management, from its beginnings in South Australia….

*Thanks to a Bay Area shoestore billboard, and Robyn Briggs ex Pacific Gas & Electric, for this!

When I managed a small subsidiary company in the 1990s, I read a book by ex ICI chair John Harvey Jones on values. He said – and I am paraphrasing wildly – that any useful organisational value must have an opposite which would work in other circumstances, otherwise it’s so much mom-and-apple-pie stuff you can’t disagree with, but which does not motivate or drive very much, either.

When my team tried articulating our collective values, we all agreed on loyalty – which the marketing men said was not an appropriate marketing slogan, so I knew we were on to something. What could be (in other contexts) a useful opposite? Impartiality, for example. Loyalty was something we felt, and it also turned out to be something our clients could feel (and appreciate). Someone else could contribute impartiality.

As we face a puzzling current widespread refusal of North American infrastructure agencies to set clear SMART targets, we have wondered aloud if it’s because they don’t want anything they could fail at. I begin to wonder if it’s worse than this, a lack of clear purpose or value at all.

I think I have just spotted the worst yet: a transportation agency that’s adopted ‘We Make People’s Lives Better’. Their top leadership are very proud of it, since who doesn’t want to Make People’s Lives Better? The detail of what counts as better, which people, how we will do this – and what we do if one lot of people want something that would adversely affect another group of people? Well, don’t be negative, we can work that all out later. (And don’t even bring up all the critiques of naïve utilitarianism.)

Do we want a bus company to ‘make our lives better’, or do we just want them to concentrate on running an efficient and comfortable bus service?

For the moment, we asset managers can play the game of what, if anything, would not fit under this rhetoric. How could it even in theory rule out a bad option?

Yeah, it was a high-priced consultancy that facilitated this, but why does this even feel right to the executive, apart from being a meaningless feelgood statement?

Is it a triumph of the marketing men, or a complete dereliction of duty?

Some days, it all feels quite hard. We know that infrastructure Asset Management requires a change in attitudes, in culture, and that’s no fun to anyone who just wants to get on and manage assets well. I teach AM, and always say that the tricky bit is attitudes, using co-operation and longer-term thinking as two culture shifts we need if we don’t have them.

But some days it seems more than this. Why does IT think IT assets are special, and so shouldn’t be subject to the same AM planning and prioritisation processes? Why doesn’t engineering care about information – not just as-built, but the need for any evidence for their decision processes. (“How do we know what benefit we will get from better information?”, an engineering department wrote recently in opposition to a data improvement initiative.) Why is Urban Planning not interested in any conversation about the current state and utilisation of the physical assets, and how did they come to despise maintenance (why does anyone despise maintenance)? Why do operations, executives think they don’t need KPIs? What do they think they are arguing for?

AM is on the side of good, evidence-based rationalism: wanting to do the right thing based on logic and facts. It is very hard for us to deal with people who are not.

Some days it feels rather like attempting to argue with an anti-vaxxer, or a Trump supporter.

Obviously, when they look at us, they don’t see champions of logic and good sense. Maybe they see a threat – but what do they tell themselves? Answers, please….

Collaborative, considered, weighing up the consequences: infrastructure does not sound typically heroic.

Looking at the language around front-line working during Covid-19, we slip very easily into ‘NHS heroes’ in a ‘fight’ against the virus. I never cease to be impressed by the dedication – on low pay, at least in England – of nurses, and of course I clapped for them along with my neighbours. My stepdaughter is an A&E paediatric nurse, so her job is reactive and high-pressure, sometimes overwhelmed.

But a conventional military image doesn’t sit well for us AM practitioners, whose role is precisely not to react. We need a cool head, not only in crisis but in the mundane everyday – not driven by the excitement of a mega project or the latest technologies.

One thing that has always appealed to me about Asset Management is how many people in infrastructure interact with their assets. ‘People who care about things’. They do not generally think of themselves as wresting victory from hostile systems, but of working with them. Understanding them; respecting them. It was an asset colleague at RailCorp in Sydney who said we are lovers, not fighters.

Public service, as nurse or asset manager, doing what we do for the sake of our communities, is what keeps society working. We need some word for it – to celebrate its worth, and praise those who do it well – but militaristic ‘heroism’ isn’t quite right. We are not ‘fighting’ anything.

Terms like ‘noble’ or ‘honourable’ appeal, but are perhaps more military than suits me, as a (frankly) physical coward who sees nothing attractive about wars.

‘Really good people’ probably doesn’t have the right ring about it. But that’s what we mean.

Why should we encourage diversity among Asset Managers? This is not just about access, equity and inclusive working environments – although there is a way to go, still, on that, even in our fairly young area.

As Janet Yellen, the USA Fed’s first female chair put it: “Beyond fairness, the lack of diversity harms the field because it wastes talent. It also skews the field’s viewpoint and diminishes its breadth.”

Asset Management is all about how people with different skills and perspectives work together to a better solution, about seeing wider than any of us can do as individuals.

What different perspective did you bring that made the difference?

I work in a group of fantastic North American Asset Management practitioners called Women in Asset Management NA, and this is the question we are tackling. We would love to hear from you.

Photo by Marcus Spiske, from unsplash.com

‘I wish it need not have happened in my time,’ said Frodo.

‘So do I,’ said Gandalf, ‘and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.’*

What do envy and the attitudes of some people responsible for infrastructure at this time have in common?

Wishing things were different, instead of getting down and actively working to change things.

This was prompted by a conversation last week with an Asset Manager struggling to get their executive to stop moaning about how unlucky it all is, and start planning for what’s going to be needed going forward from Covid-19. People paid a goodly amount of money to take responsibility, who instead are acting like victims: everything would have been ok, if only….

Wanting the world on your own terms is not a strategy. Managing assets is for life, not just for Christmas, not just the good times.

It made me think again how vital the principle of honesty is for good infrastructure management. Chris Lloyd and Charles Johnson in their Seven Revelations of Asset Management (Assets, May 2014) put it like this: Asset Management demands openness about past performance. We have to face up to what’s gone on before, how well (or how badly) the assets are doing.

But we also have to honestly face up to change – even when it looks calamitous. That is what responsibility means.

Even discussing the deadly sins soon comes round to Asset Management!

The serious point is how we build up that sense of responsibility, in ourselves and in top management, to do our level best with what we have taken on. To commit to be better informed, better trained, to learn from best practice and to live it.

No-one forces anyone else to involve themselves in crucial infrastructure. You do not have to apply to be CEO of a public service, or run for election to the Council – but, having made that choice, it’s not a cushy number.

*J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

Recent Comments