If you are planning to attend our Sydney celebration, please RSVP to: amis40@talkinginfrastructure.com so we can keep an eye on numbers – limited to the first 60! Event is free, includes food and discussion with Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda and a whole heap of old friends and colleagues.

Full update of the 40th year celebration events shortly!

Join us at the Harbour View Hotel in the Rocks and help celebrate with finger food and drinks – plus Penny and Jeff on what we have learnt from the last 40 years to help us meet the challenges of the next 40.

Many thanks to Richard Edwards, Lynn Furniss and Matt Miles of AMCL

Penny Burns and Talking Infrastructure will be on the move in April to celebrate 40 years of Asset Management, and look forward to the next 40.

Adelaide April 15 & 16, Penny and Ruth will be celebrating at AM Peak.

Brisbane events April 17-19

Sydney April 24, venue TBC: Asset Valuation in a time of Climate Crisis. Including Jeff Roorda on how Blue Mountains City Council is taking a radically new approach, as well as Penny on how we must rethink our AMP modelling.

Melbourne April 30, IPWC. Penny speaking on the opening morning of IPWEA conference

Wellington May 4-6, events to be announced

Let us know if you are interested in meeting up in any of these cities.

See you in April! #AMis40

One of my great pleasures in life is to sit in a café and talk infrastructure. A popular topic, even before Lou Cripps came up with the idea Asset Managers are platypuses, is what makes an effective one? Or even what attracts us in the first place.

Who are ‘our people’?

To defend us from accusations of exclusivity, I need to point out that it’s not about what you studied at university, or which country you grew up in. Good Asset Managers are ‘anywheres’, as Ark Wingrove put it.

This is, of course, a Serious Subject, as we desperately seek to switch to a future-friendly mindset; seeing the bigger, longer picture around physical assets. But it’s also kinda fun to think about the difference that makes a difference.

Like the AM team who came on one of my courses and took me literally. We teach whole life costs, cost-risk optimisation, thinking in risk, and how information is all about decision-making. But I don’t think most attendees go away and start actually doing any of that. This team did.

One reason people don’t try whole life cost modelling, or risks in $, is because they think it’s too hard before they even start.

But my best students – well, if that was how you do Asset Management, they would figure out how to do it. When I later asked Todd Sheperd how they quantified asset risk, he said he looked it up on the internet. After reading a recommended book and going on a recommended course. (As I said, he took me literally.)

Yes, he must have had the confidence to believe he and his team could figure it out. But I think it’s more than that. It’s about curiosity and openness to learning.

It also involves a belief that if I don’t know something, someone else may have worked it out, maybe in a completely different context. We can learn from others – like 17th century gambling mathematicians, or stock markets traders.

Or actuaries. It’s as if 99% of attendees on AM courses have never heard there is a whole profession who have worked out how to put $ on risks.

Sitting in a café recently with Todd and Julie DeYoung talking about infrastructure, we also recognised another quality: interest in what we can learn from people doing something that’s not exactly the same as what we’re trying to do. Like wondering what we can learn from assets that aren’t exactly what we have – instead of deciding ‘our’ assets are so special there is nothing we can learn from others (and the processes of AM planning and modelling don’t apply to us).

In other cafés years ago with another old AM friend, Christine Ashton, we thought it’s about pattern matching. About looking at a problem we had, and the kind of technology approach it needed, as opposed to a fixation on a particular software tool, for example. What kind of problem is it? What sort of tool could help?

To me that’s linked to 80:20 thinking, but I suspect that some of my best AM buddies are better at details than me. It’s happily straying into the unknown, instead of trying to force everything to fit into what you already know.

I love (nearly) all of my students, of course. But not all of them turn out to be my sort of café people.

Shout out to yet another recent café and Janel Ulrich – her of the ‘can we develop our SAMP in the next 12 hours?’ (yes, of course we can). I love the way she loves ‘our kind of people’, in all our quirks and heartaches and irrepressible openness.

Others who will recognise their café contributions include John Lavan and Manjit Bains. And Penny, with whom too many of these café conversations have to be virtual.

Someone I work with in the UK nuclear industry asks in despair, how come project engineers don’t feel that the whole point of building something is for it to operate? In other words, that construction projects only exist to create something that will be used to deliver products and services.

Why aren’t they interested in the long-term use that comes after construction?

If it really is all about use, they really need to consider what is required to use the asset. They should be interested!

This isn’t just to focus on what service we need to deliver. The asset has no point unless it delivers a service that is needed. Even project engineers can get that.

What we continue to struggle with is getting asset construction engineers and project managers to consider what is needed in order to use it successfully. And this includes providing as-built data – what assets are there to operate – and thinking ahead on operating strategy, and maintenance schedules. It’s designing and building with the operations and maintenance in mind. Designing for operability and maintainability.

In infrastructure, the asset ‘users’ are often not the customers, who may never touch or even see the assets. The people who use the assets are the operators; the people who touch the assets, maintenance.

An engineering design goes through many hands before it impacts on the customer – and if those hands in between are hamstrung by designs that are poor to operate, hard to maintain, and by the incomplete thinking that ‘throws the assets over the wall’ at operations (as we used to say in the UK) without adequate information – what is the point, really?

I believe there may be something called project time, where there is no ‘after’. No ‘and then what?’ – just onto the next shiny thing to build.

Thanks again to Bill Wallsgrove

Human beings may not naturally be good at thinking about the future.

One thought is that, just like with charity appeals for current disasters, we should focus on an individual. Think ourselves into the shoes of some one as they experience the future.

It could be ourselves, a grandchild (if we have one), a ‘descendant’ – or anyone we can picture.

A startling powerful example of this appears in the first chapter of Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future, published in 2020. The author specialises in thoughtful, ‘realistic’ depictions of the future, for example in colonising Mars.

The Ministry for the Future starts by describing the experience of one Western man in a climate catastrophe, when twenty million people in northern India die in a heat wave. Many millions in a faraway country in the future: a newspaper headline. And ‘Frank May’, who works in a clinic near Lucknow, who nearly poaches to death in a lake full of people, where the water is above the temperature of blood.

I could not get the image of him out of my head for a lot longer than a headline.

I realised when watching the final episode of Planet Earth 3 last month that the image of Frank May was so vivid that it felt it was happening right now. It was not hypothetical, despite being fiction.

We may overdo the image of threats to a panda or polar bear or orangutan, to be invited to imagine a world without them. Just like we stop reacting to doe-eyed young children in charity ads. But I suspect we simply need this emotional connection.

Maybe like the Japanese traditionally put on the garment of a descendant, to feel how they will perceive the results of what we are doing now. We too could do this, to really feel it when we make a decision now about their infrastructure in fifty years’ time.

A technique to consider next time we are involved in long term asset decisions?

My colleague Todd Shepherd and I had a brainwave* last year to restructure how we teach Asset Management – not as a line that starts with investigating capital needs, the conventional beginning of the asset life cycle, but from where we are now. That is, right in the middle of maintenance. We are always deep in maintenance needs.

It makes more sense of the history of AM, straight off. It was not people writing business cases, or design engineers, who realised the urgent need for something different. It was maintenance, post World War 2, and then Penny Burns and the problem of unfunded replacements and renewals in the 1980s.

If Asset Management has waves, we might suggest what Wave Minus 1 was. Wave Minus 1 was hero engineers, from the Industrial Revolution on, building heroic infrastructure – Bazalgette and London sewers, Brooklyn Bridge. Sewers and bridges are both good things. But they are not quite such good things if they leak or fall down because they are not maintained or renewed.

With infrastructure, it is not enough to start; you have to see it through.

Penny used life cycle models to understand the extent of renewals, and increasingly I don’t feel anyone is really doing Asset Management if they do not use such models. Of course it is called life cycle for a reason. There isn’t an end, only another cycle.

But now I fear that starting at the beginning of one lifecycle in our teaching still makes it sound as though it is the creation of infrastructure that’s the important thing. We have not really got the cycle bit across enough, at least to the average engineer we teach. What comes after construction is still a vague future state, that is someone else’s problem.

And, not at all coincidentally, that’s also the point of the circular economy concept. There is no meaningful product end, and we are right in the middle of the mess we already built.

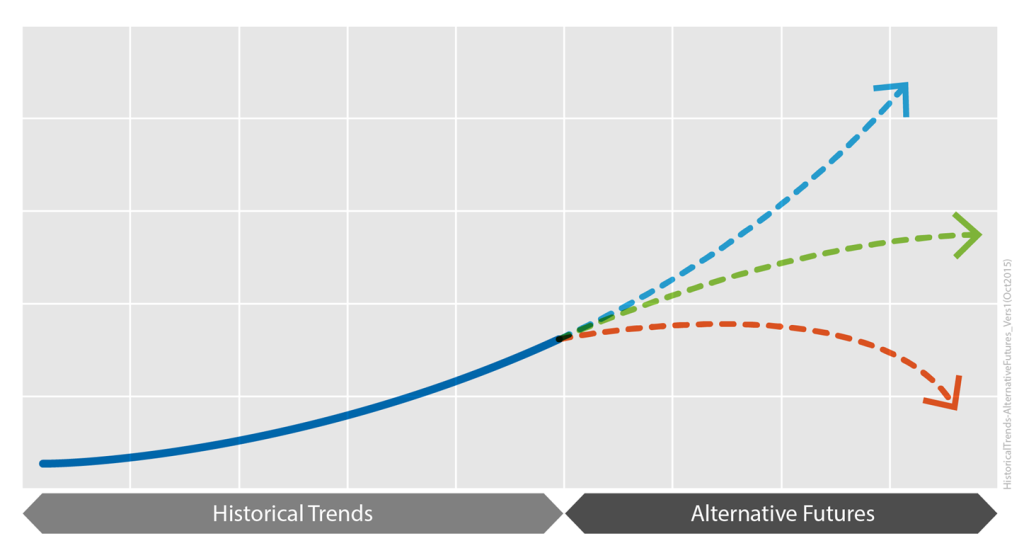

It is not a straight line into the future, where we set assets in motion and let them go. Longer term thinking, long-termism, has to think in cycles.

*Almost certainly it was Todd’s brainwave, which I managed to catch up with.

Thanks to my brother Bill Wallsgrove

Board member Lou Cripps and his team at RTD are great Asset Management practitioners – and that is largely because of their attitude to time.

For example, the team prepares carefully for meetings with key stakeholders, not just the CEO but engineers, IT, maintenance, HR. They think carefully about what they want to effect through the meeting – their objectives – and then project forward what the possible response/s of the others will be, based on their previous interactions. They can then work on what will most connect and make a win:win outcome likely.

Lou’s team also makes full use of red-teaming and pre-mortems, to imagine what could go wrong with an initiative so they can prepare not to go there. Risk assessments and risk plans, essentially, but exploiting the human ability to project forward and then ‘look back’ in our minds. (“Imagine it’s six months’ time and we are doing a post-mortem on what went wrong.”)

Lou refers often to ‘future me’ and ‘future us’: that is, stepping in the shoes of himself in a year or ten years’ time. This is not just to feel how fed up he might be then about what he failed to do now, but also to consider what future him would care about more widely. It is empathy with a future self. And it does not even need to be yourself. What about someone in the community in a hundred years?

This is good Asset Management for infrastructure, in particular, as infrastructure decisions we make now should always be assumed to have lasting implications. The assets we build now may still be in use in a hundred years. And the things we don’t build because we’re building something else. The lost opportunities, and future debts. What we fail to maintain, so will have to be built again…

Lou’s team last year relentlessly analysed the data to work out the likely costs – the total costs, now and into the future – for a proposed project to buy more electric buses. They worked out that this particular set-up would cost their transit agency approximately $2 a mile extra on every electric route for the next 50 years. It wouldn’t even save on carbon, because the electricity supply proposed was fossil fuel burning generation. (It was not a good proposal, and the Board duly turned it down thanks to their analysis.)

To build and not think ahead is a dereliction of duty. Principle number one for an Asset Manager: always ask, “And then what?”

Making full use of the past, in order to think ourselves into the future.

How do you this in your team?

In 2024, Asset Management turns forty.

One key question for me this year as an Asset Management practitioner is time itself, and how we act with the future in mind.

The innovation of Asset Management is very largely about time. Penny Burns created AM to look forward in time and consciously choose whether we needed to renew like-for-like, or should manage our assets differently in future.

Forty years ago, we were not thinking about climate catastrophe, and we were only just at the start of the IT revolution. (I had only just seen my first PC, and the world wide web, smart phones and terabytes of data storage for $50 were barely pipedreams.)

But the question of longer-term thinking has in some ways gone backwards in our societies since then, not forwards.

The vast majority of infrastructure organisations still only have very short term asset plans, and almost no asset strategy. More have, must have, 3- or 5-year plans now, thanks to AM as much as anything. But the 15 to 20 years plus strategic view that Penny proposed is still a challenge.

And shockingly few agencies even use life cycle modelling to project the very basic realities about the timings for replacements, let alone a mindset of always asking ‘And then what?’ of our day to day and year to year asset decisions.

I fear as a community we are still underskilled, underprepared for the future: for embracing uncertainty and identifying with the future.

And so, as we celebrate, look back and learn from the last 40 years, Talking Infrastructure plans to act like the future matters.

Starting with a time series of blogs to ring in the New Year. Your contributions most welcome!

Recent Comments