In May 2018, Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda wrote here about three ‘revolutions’ in Asset Management – later renamed ‘waves’, because that captures better the idea that one wave doesn’t supersede another.

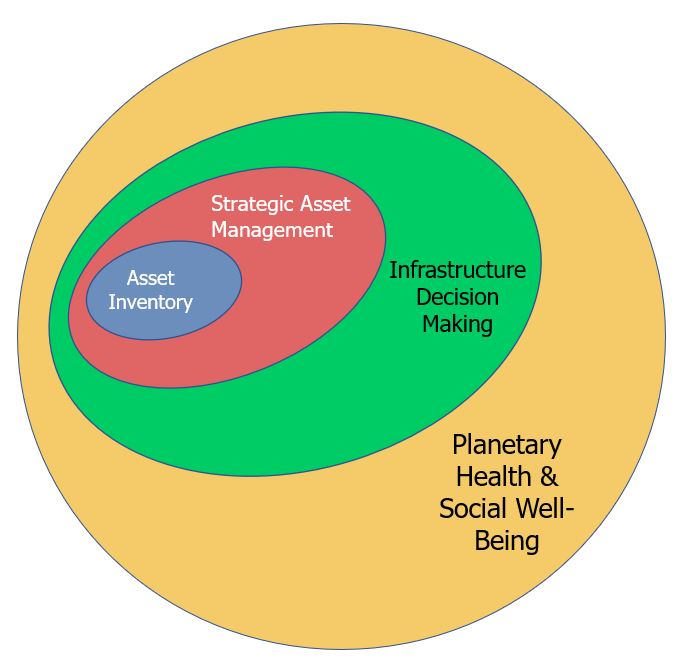

Since then, we have discussed with each other and many others how Wave 1, ‘Asset Inventory’, is more successful if you already have in mind the vision of Wave 2, ‘Strategic Asset Management’ and how you are going to use all of the information you collect.

We have looked at what Asset Management practitioners need to develop to move on from this, to be able to look beyond our own organisations, to a bigger role in supporting our communities. We called this Wave 3, supporting better ‘Infrastructure Decision Making’.

We have even begun to imagine Wave 4.

As Penny puts it: whereas Wave 1 looked at WHAT we had, and Wave 2 looked at HOW we needed to manage it, Wave 3 started to ask WHO we were serving by our efforts. This has brought us now to start thinking more deeply about this question and about the next move, looking at the critical question of WHY.

As Asset Management practitioners, we have to ensure we are in the right positions of influence to be able to challenge existing infrastructure assumptions, which is what I think Wave 3 is all about. To look ‘up and out’, as Lou Cripps of RTD puts it.

But we can already spot that there is no point in being able to ask hard questions, if we don’t have the right questions to ask….

What do we mean by ‘better’?

I teach people about Asset Management – up to 1000 a year – and I get to see a wide range of reactions. Best is when someone in class decides Asset Management is what they have been looking for their whole career, its mixture of technical and people and business challenges exactly right for them. Or the maintenance guy who, by the end of the course, was explaining to everyone else to “do the math” for optimal decisions.

For some, on intro courses, it’s mildly interesting, at least as long as their leaders tell them it is.

Sometimes, however, people resist.

I taught a class of design engineers a few years ago, who argued the toss on everything, and failed the exam afterwards. I think we can take it that they didn’t get it because they didn’t want to. (I have also taught a class to project engineers who had understood AM was the way forward for them personally and had got together to sign up for it.)

Recently, I was working with an organisation – an early-ish adopter in the USA – where they were keen enough on AM to create a series of jobs for ‘Asset Manager’. Not necessarily what I, personally, would call Asset Managers, but rather engineering roles to develop priorities by asset class for replacement capital projects.

The way we teach AM, following the lead of Richard Edwards and Chris Lloyd (two very smart UK pioneers) is top down. If strategic AM is aligned to organisation priorities and levels of service targets, we start with what those targets are, with external stakeholders interests, the role of top management, and demand forecasting. In other words, context and goals. I warn everyone about this right at the start – and also make it clear that nothing else matters if we don’t understand what we want the assets for in the first place.

I was struck, this time, by the lack of curiosity the class had. No-one knew what their level of service targets were, they stumbled to think about who their key regulators were, where demand was heading, even who might have a legitimate interest in what assets were being replaced, outside of engineering and operations. It wasn’t just that they didn’t know, they also didn’t much care. They were not stupid.

I was struck by how weird it is, really, that we have to teach anyone about alignment. That smart people working with assets don’t stop to ask what their organisations are really doing with those assets.

What a good Asset Manager really needs more than anything is curiosity – asking all the questions about why and how and how we can do it better in future.

But some people just aren’t very curious, for some reason. They are not much fun to teach!

Dreamstime.com/ 187958062 © Meg Forbes

The world of infrastructure Asset Management has had the benefit of an evolutionary model for several years: the ‘Waves’ of Penny Burns, to make sense of how organisations seem to have to go through a period of focus on basic information (Wave 1, Asset Inventory) before they really look at how to use it to make better decisions, to start optimising (Wave 2, Strategic Asset Management).

Before that, I confess, I struggled to express what was going on: how could people get stuck in data and databases? I don’t know that I fully understand, still, but I least I recognise it now – that having a list of all your assets, simple facts like install date and location, and a big dumb database to put it all in preoccupied so many of us for so long.

Penny herself seems not to have spent too much time worrying about this, but always had a vision way beyond it. She assumed we would have a grip on lifecycle costs, thinking longer term, and planning ahead, and get down to acting smarter on our asset decisions.

And now, as we work together to capture our collective history and development, we are really looking forward to the next Wave. To really so much better infrastructure decision making that is fit for purpose, through the rest of this turbulent century.

Look out for celebrating our history on July 29th!

Dreamstime.com/ 191317844 © Lefteris Papaulakis

It’s always an interesting question: why do things arise when and where they do? Why Asset Management in Australia in the 1980s, when plenty of other useful asset ideas came from other places and times – reliability engineering in US commercial airlines post-war, for instance?

And when I explain where much best practice comes from, why is New Zealand such a paragon? There are very good reasons, when you ask about the when and the where.

There is something about fundamental ideas that makes understanding the specifics important. An approach that seems like such a good idea as Asset Management – why wasn’t it more obvious, earlier, to more people? A fabulous clue as to how what seems like an obviously sensible mindset, required something major to shift. A chink in older assumptions, even culture, that let someone, something start to question, to let a new light in.

I suspect a lot of us struggle about why people resist what seems backed by logic, evidence and good sense. But I don’t want us to go down the deep, dangerous rabbit hole that is conventional economics, making a simplifying assumption that people are ‘rational’ the way they define it – a definition which doesn’t really care why people do what they do, or how what seems ‘obvious’ in one situation doesn’t work in another, or anywhere.

And that is partly why I love physical infrastructure. One size really doesn’t fit all* – a good strategy for one kind of asset would be barking wrong for another, and even for an identical asset in a different context. And it all depends on what you are trying to achieve, specifically.

Physical assets are the opposite of idealised generalisations. Yes, there are generally good questions; but not universal good answers, at least not in my experience.

Infrastructure Asset Management is the epitome of the full appreciation of time and place.

Watch here for the publication of the first part of Penny Burns’ history of Asset Management, from its beginnings in South Australia….

*Thanks to a Bay Area shoestore billboard, and Robyn Briggs ex Pacific Gas & Electric, for this!

© The Walt Disney Company

Appealing though it might be to be a secret hero*, like Fedora Perry – cool hat! – even this misunderstands platypuses. The internet has plenty of cute images of things that are labelled platypuses but aren’t.

In particular, many cartoons (like Perry) show them with a beaver tail*. They are sort of like an Australian beaver, so we assume they look like them. Even the robot platypus has a beaver tail. But platypuses have furry tails.

Once someone put a beaver tail on a platypus, it was easier for people to copy than check a photo of a real platypus*.

And I guess they were the inspiration for Fantastic Beast the niffler – and now nifflers show up in seaches for platypus images.

And since almost no-one has ever seen a baby platypus*, fake pictures circulate (and there’s a furious debate about what they are even called).

Yes, platypuses are widely misunderstood, when people have even heard of them.

What does a good infrastructure Asset Manager really do*?

*Hint: not a lone hero, not a construction engineer, not necessarily what people think, and they don’t spring fully formed from college…

Dreamstime.com/ 38357225 © Bogdancaraman

One thing that puzzles me in the world is the desire of many to be more excited by what technology could do to emulate people than about people themselves. Why are Asset Management conferences packed with papers about data, and usually silent about what human beings bring to decision-making?

Even those who should know better (because they have been there) talk about ‘data-driven’ processes; and organisations pour far more money into dumb databases than getting a better understanding of their assets.

I suspect this is partly the fetish for capital over on-going costs – and, frankly, ideological faith that it’s better to invest in ‘innovation’ than labour costs. Anything that promises to cut staff is good, no matter how much it costs to try to replace them.

Now, I am a big sci-fi fan, which generally accepts the forward march of technology. But then again, it also warns about how it can wrong, at least in the stories I read. I am not at all sure replacing people with robots benefits anyone, and not the 99% of us that don’t control how automation is used. I am not especially optimistic.

However, there is one thing I am pretty certain about, even in embracing uncertainty about the future: no-one really has any clue about how we can replace experience in managing physical assets.

I remember when I first noticed that investment in things like work management systems, or even more basic computerised processes, could lose sight of how things really work. Big IT in the 1990s in asset-world was sold as replacing some administration costs – mostly part time, middle aged women, who cost almost nothing as they were paid very little, who managed the monthly reporting, knew where the data was, what it meant to asset decision makers, and what to do with it. And the local nerds who programmed in Fortran in their spare time, and wrote routines for their next door colleagues to do any analysis or maths required.

At least we might try to learn the lessons from the history of IT: where did it work, and why?

Which, to me, includes the question of how to think of technology as a tool to assist skilled people. Why would we even want to see ourselves replaced?

In writing Building an Asset Management Team, Lou Cripps and I looked at the skills an effective Asset Management team requires – both technical and business understanding, good grasp of front-line experience, both system and structured thinking, a longer term perspective, emotional intelligence and communication skills, embracing uncertainty and the tools to think about risk, integrity, and enough leadership ability to get others to buy into a new way of working.

Good infrastructure Asset Management requires a tricky combination of attributes.

Lou came up with the image of the platypus, that is very rare and not to be found on most continents.

Instead of searching for an amphibious, duck-billed, otter-footed, egg-laying, venomous mammal that locates prey through electroreception, it’s easier to provide all the qualities we need through a complementary team.

But we still love platypuses. Watch out for more of them in the next ten days!

“The worst misunderstandings sometimes happen between different teams within the supposedly same ethnic group, particularly if they [come] from different locations or had different professional training (say, IT workers mingling with engineers)” – Gillian Tett

I have long been fascinated by differences in approach between engineers and Asset Management professionals – how AM is not just another variety of engineering. And, for that matter, why Operations managers don’t think like AMps, or how IT teams look at the world. For instance: what is it that motivates people in IT teams? (Not, I think, the pleasures of making users happy.)

In my own life, I seem to have sharply favoured working with maintenance, or ex-maintenance people, rather than Engineers with Capital E. Because they were very different experiences.

It is not that there have not been engineers who are massively important to me, such as my brother, or my parents’ best friend Ed – but then again, they never acted like typical engineers, and were not very polite about such ‘grey men’ (Ed’s phrase) themselves. That engineering does have its own cultural norms, some quite odd, has been a question for me for many decades.

So my eye was caught by the review of a book by Financial Times editor Gillian Tett, Anthro-Vision: How Anthropology Can Explain Business and Life. About trained anthropologists such as Tett who have found themselves working in businesses, such as Google or GM, or what they would advise governments on dealing with COVID-19.

She describes how anthropology is about both investigating what’s strange, other, exotic, and about the tools to see our own culture/s, to understand what is weird (or even WEIRD) about it. The book has plenty of interesting examples – about Kit Kats in Japan become an indispensable good luck charm for school exams, about dealing with Ebola or ‘CDOs’, as well as more effective advertising and work practices.

But it particularly made me think of how to understand the oddities of current engineering – why is so often tends towards the short term, to silos and uncoordinated stupidity, even resistance to data. Surely none of those attitudes are ‘logical’ – so what is really going on? I take it as given that, like IT, there is a coherent motivation, a vision of what it means to be a good engineer. So how come… that doesn’t play nice with Asset Management, so often?

And then again… what is the culture of Asset Management, developing before our eyes?

Because I also take it that if you don’t try to understand the water you swim in, you also don’t really understand what you are doing – how it might need to change or evolve – and why it gets up the nose of others who don’t share your basic values.

There is always culture, always weird to someone outside it, and managing infrastructure involves several different ones. So we must have anthropology in our Asset Management toolkits, too!

Next: Ethnographic approaches we might use in practice?

When I managed a small subsidiary company in the 1990s, I read a book by ex ICI chair John Harvey Jones on values. He said – and I am paraphrasing wildly – that any useful organisational value must have an opposite which would work in other circumstances, otherwise it’s so much mom-and-apple-pie stuff you can’t disagree with, but which does not motivate or drive very much, either.

When my team tried articulating our collective values, we all agreed on loyalty – which the marketing men said was not an appropriate marketing slogan, so I knew we were on to something. What could be (in other contexts) a useful opposite? Impartiality, for example. Loyalty was something we felt, and it also turned out to be something our clients could feel (and appreciate). Someone else could contribute impartiality.

As we face a puzzling current widespread refusal of North American infrastructure agencies to set clear SMART targets, we have wondered aloud if it’s because they don’t want anything they could fail at. I begin to wonder if it’s worse than this, a lack of clear purpose or value at all.

I think I have just spotted the worst yet: a transportation agency that’s adopted ‘We Make People’s Lives Better’. Their top leadership are very proud of it, since who doesn’t want to Make People’s Lives Better? The detail of what counts as better, which people, how we will do this – and what we do if one lot of people want something that would adversely affect another group of people? Well, don’t be negative, we can work that all out later. (And don’t even bring up all the critiques of naïve utilitarianism.)

Do we want a bus company to ‘make our lives better’, or do we just want them to concentrate on running an efficient and comfortable bus service?

For the moment, we asset managers can play the game of what, if anything, would not fit under this rhetoric. How could it even in theory rule out a bad option?

Yeah, it was a high-priced consultancy that facilitated this, but why does this even feel right to the executive, apart from being a meaningless feelgood statement?

Is it a triumph of the marketing men, or a complete dereliction of duty?

Some days, it all feels quite hard. We know that infrastructure Asset Management requires a change in attitudes, in culture, and that’s no fun to anyone who just wants to get on and manage assets well. I teach AM, and always say that the tricky bit is attitudes, using co-operation and longer-term thinking as two culture shifts we need if we don’t have them.

But some days it seems more than this. Why does IT think IT assets are special, and so shouldn’t be subject to the same AM planning and prioritisation processes? Why doesn’t engineering care about information – not just as-built, but the need for any evidence for their decision processes. (“How do we know what benefit we will get from better information?”, an engineering department wrote recently in opposition to a data improvement initiative.) Why is Urban Planning not interested in any conversation about the current state and utilisation of the physical assets, and how did they come to despise maintenance (why does anyone despise maintenance)? Why do operations, executives think they don’t need KPIs? What do they think they are arguing for?

AM is on the side of good, evidence-based rationalism: wanting to do the right thing based on logic and facts. It is very hard for us to deal with people who are not.

Some days it feels rather like attempting to argue with an anti-vaxxer, or a Trump supporter.

Obviously, when they look at us, they don’t see champions of logic and good sense. Maybe they see a threat – but what do they tell themselves? Answers, please….

Recent Comments