More than a decade ago, Chris Lloyd and Charles Johnson wrote in the Seven Revelations of Asset Management that we must “embrace uncertainty”.

This year we want to build on good practice to help our profession do this.

Let’s cut to the chase: our role as asset managers is to develop plans for the future, and yet the future, even next week, is uncertain. (Particularly at the moment.) We can’t not plan because we don’t know everything. In fact, uncertainty makes it even more essential to have plans.

Chris and Charles were right: we have to leap in.

It’s better to be roughly right than perfectly wrong. And there is no other option. Aiming for certainty is how we would ensure we are adding little value to asset decisions.

Board member Todd Shepherd has worked in North American power and water to develop a better approach to infrastructure risk and uncertainty, based on good practice in other professions and sectors. It’s not about a new tool, not software, but a more fundamental understanding of what managing uncertainty requires.

It requires not even trying to get a perfect answer.

Because the cost of perfect information is infinite – impossible. And good decisions don’t need it. What’s needed from us is practical ways to reduce our organisations’ uncertainty.

We’re currently drafting a much longer piece about how we make better decisions through better estimating and grasp of probabilities. And how it is, in the end, easier to deal with uncertainty than some of the weird things we do in infrastructure at the moment.

Are you in with us?

(We’d love to hear from you on risk.)

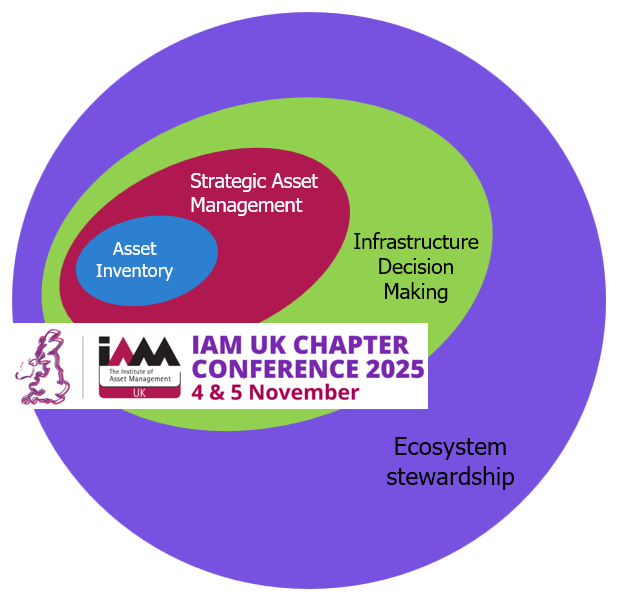

Our mission at Talking Infrastructure is to promote the good practices of Asset Management Wave 2 and develop thinking on Waves 3 and 4.

It’s an evolutionary model: you need the solid processes of whole life costing, sophisticated risk thinking, and longer-term asset planning both for the sake of your own organisation’s ability to deliver and to underpin (to ground) decisions on new infrastructure and new types of assets.

So we plan to:

- Continue to promote better strategic Asset Management, Wave 2, through re-emphasising the core AM tool of longer-term asset planning as well as development of more sophisticated asset risk and decision-making concepts

- Develop a guidebook to the AMP, to restate and update Penny’s original vision for the changing contexts of the 2020s, with case studies such as Grant County PUD

- We would also like to see campaigning for infrastructure regulators to have more teeth through AMP requirements and audits to encourage agencies to plan ahead

Plan for work on Wave 3, infrastructure decision making especially on new and renewed assets includes:

- Promote work already done, such as the UK Projects and Infrastructure Project Routemap module on Asset Management, https://projectdelivery.gov.uk/library-product/project-routemap-asset-management-module/ and our latest book Legacy: A Decision Maker’s Guide to Infrastructure

- There is a still a long way to go to shift from a construction delivery and short-term profit focus to planning the right assets and asset strategies in the first place. Shout out to Louise Hart working on how to succeed at infrastructure megaprojects (linkedin.com/in/louisehart750), and Johannes Paradza of Infrastructure Asset Management South Africa on how asset managers help meet the challenge of Cape Town’s infrastructure.

Resources on Wave 4, starting with Jeff’s work as Director of Infrastructure and Biodiversity at the Blue Mountains City Council

For all of these, we aim to build on friendly alliances with like-minded people and organisations.

Your input, please, on:

- In your experience, in what ways is Wave 2, strategic Asset Management, still not yet where we should be?

- Anything you already know of on Wave 3, better infrastructure decision-making in our communities?

- Inspiring examples on resilience, biodiversity, radically sustainable thinking on assets – away from grey assets?

What’s in your plan for 2026?

Just because it reminded us of the computer in the original BBC Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

This year, Asset Management turns 42. And we all know what that means…

Is there one, main thing we can do in organisations that will lead to good Asset Management?

On the one hand, 39, now 40 subject areas, ISO 55000 clauses, and AM maturity assessments with tens if not hundreds of questions all suggest there are many things we have to do.

On the other, some of us suspect AM is a paradigm which may only need one assumption to be thoroughly overturned to flip the system.

If I had to bet, it would be the concept of an asset lifecycle model – a model not really about money, but what we need to do to an asset, or an asset class, to effectively manage it over time to meet demand.

However, the evidence for this is more, as they say, in the breach: most infrastructure organisations haven’t yet got explicit whole of life models. Have not tried this switch.

But watch this space…

Next comes a blog summarising what Talking Infrastructure needs to do in 2026. How about you?

Happy New Year from the Talking Infrastructure Board!

In our ongoing campaign to educate everyone about platypus tails: forget Perry the Platypus, they do not look like beaver tails!

Platypuses have furry prehensile tails, in other words they can grasp objects with them. This still from a reel isn’t very clear, but she is carrying twigs.

“When female platypuses are making nests, they will grab bunches of vegetation with their flat little prehensile tails and drag the foliage into their burrows.”*

Yet more platypus versatility.

Another reason they are my totem animal and symbol of Asset Management at work.

Seasons’ greetings and a very happy 2026 to all platypuses & Asset Managers

*See podcast Ornithorhynchology (PLATYPUSES) by Alie Ward for more platypology

ID 26212151 | Child In Shallow © Pavla Zakova | Dreamstime.com

When we look back at the history of Asset Management, there is one curious feature.

In a world in which many people go on about data, many act like the revolution of AM is the discovery of asset data.

Why?

Penny many years ago made the point – well, that the point is making better long-term decisions about assets. Wave 1, ‘asset inventory’, only has any value when we use such data to make better decisions, in Penny’s Wave 2: strategic asset management. As Penny says, when you focus on the decisions, you have a much clearer idea of what data you actually need. Wave 2 improves Wave 1.

But there must be some kind of reason why organisations seem to have to go through Wave 1, collecting and organising data, first.

Cynically, we might think it’s because it’s easier than questioning decision-making: something middle level asset managers can do without challenging business at the top level. Or, and/or, there are plenty of suppliers willing to sell you help in collecting data or implementing the transactional IT systems to put it in. Few that actually know how to make better decisions.

But I come to suspect that, weirdly, asset-centric data is more radical than it sounds. What suggests this is how hard other teams kick and scream about collecting and handing on asset inventory, the very basic data on what assets we have where. (Capital projects, IT, even some maintenance teams.)

It doesn’t seem to help to stress that we cannot manage what we don’t know we have. Is the problem that they don’t understand that we do have to continue to manage assets into the future?

Or is it – back to basics – that the whole concept of an asset is the first revolution?

Other people manage projects, budgets, sites, even value on the balance sheet. Only Asset Management believes the fundamental unit of management is the operational asset.

Can we rewrite the advice on implementing Asset Management to get us to decisions faster?

Are too many organisations still not making that very first leap into the water?

Memorial to Jules Verne, Amiens, ID 381624172 © Linda Williams | Dreamstime.com

One way to put my life in context is: when I was born, Robert Heinlein was king of science fiction.

Not that I knew this until ten or so years later, when I started to read my family’s collection of sci fi Penguins. We, naturally, also favoured British writers, who, if not noticeably more female or non-white, were at least less American gung-ho.

Now, the world of the future is very different, with some ‘non-binary’ writers, Afrofuturism, and radical ecologies. And good aliens, my favourite.

Between then and now, there have been a lot of post-apocalyptic dystopias, which I tend to keep away from. Post-scarcity anarchism is much more my thing (see Ursula K LeGuin, and Iain M Banks’ ‘Culture’, for example).

And hope.

If one defining feature of good Asset Management is developing longer term planning, and infrastructure urgently requires a future vision, can hopeful science fiction help us?

What’s your most inspiring example of a fictional future?

And a vision of future infrastructure?

Just after Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda wrote about the revolutions or ‘waves’ of Asset Management in 2018, I realised how useful this was for surviving Asset Management conferences.

Sitting through yet another presentation about asset data, I thought: too many of us are still stuck in wave 1, asset inventory. Oh, for more papers on wave 2 and actually using information for making better strategic asset decisions! It’s not just my problem!

I had the great pleasure of attending a conference this month when not only did I not sit through anything on data, BIM, digital twins or AI, but we actually looked forward to waves 3 and 4.

The IAM UK conference, curated by Ursula Bryan – I really have to give her the credit – including an AM professional talking about how to use AM to solve Cape Town’s infrastructure challenge. That is truly wave 3 looking up and out. And another presentation about using AM to redefine coasts: a vision of wave 4.

At the conference I only addressed wave 2 with my US AM mob, about how most organisations still have to implement lifecycle based longer term planning.

But it was fantastically heartening to put this in the context of more ambitious Asset Management. Shout-outs to Johannes Paradza of Infrastructure Asset Management South Africa, and the always visionary Joe Inniss and Ashley Barrett of their Centre for Asset Studies!

See ‘Amphibious Infrastructure’, https://www.centreforassetstudies.co.uk/articles

Excavation at Star Carr in Yorkshire, bbc.com

If I had the brain capacity, I’d write a book called something grandiose like Infrastructure and Civilisation. To bring out just how important working infrastructure is to us.

You can’t have ‘civilisation’ – people living in towns and cities – without it. How did it grow, from the earliest actions to build shared causeways? We are handy, but it must be more than that.

I just read an interesting book called Inheritance: The Evolutionary Origins of the Modern World. It’s by Harvey Whitehouse, an anthropologist who also conducts psychology experiments on small children and co-compiled a database of hundreds of cultures already studied by anthropologists and archaeologists to analyse for key factors – as I said, interesting.

It made me reflect that both modern society and physical infrastructure require two things: co-operation between people (to build and maintain far larger social and physical structures than one person or even family could do) and sanctions, in other words ways to get people to do, or not do, things.*

Both have their origins well before homo sapiens, of course. Primates are largely social co-operators – and have strong views of what’s not fair, that they will go out of their way to punish. Sanctions for anyone not behaving well don’t have to involve written laws or dedicated police: for a social animal whose life depends on co-operation, disapproval works well on its own.

I grew up with a just-so story about competition being the motive force of progress, but it is much, much more interesting to look at how people work together.

It’s certainly my experience of infrastructure. 99% co-operation with some rules and regulation to force social-mindedness where necessary.

(And my current read is Progress, A History of Humanity’s Worst Idea!)

What’s the required balance of co-operation and rules for sustainable infrastructure?

*Whitehouse talks about why slavery did not in the end work out – why it’s more effective to get people to co-operate, when you grasp our basic psychology.

30199342 | Happy © Michal Bednarek | Dreamstime.com

They say you should not have favourites among your children. But I found it impossible not to have favourite clients.

I always enjoyed some individuals, some asset managers in particular. More than being nice people – which they were – it was about understanding each other, speaking the same language. Many others I worked with over 30-plus years simply didn’t get what we were saying.

In another lifetime, I would love to figure out why I warmed to some regions more than others: why I loved asset managers in Indonesia, Malaysia, some Canada, west coast USA – and New Zealand, of course.

But favourite clients also include organisations run by the more visionary executives.

I did not always get near the C suite, or councillors. But my fondest working memories now are for those who were engaged. Taking me back to almost my earliest discussions about Asset Management change, about what is and is not possible unless there is a CEO who gets it.

Sometimes there were executives who almost got it, and those are not such happy memories. Some of them even know who they are, because I got to the point when I said this out loud, that they were not succeeding at Asset Management because of the bizarre choices they made. That they were the problem.

Happier to think about how much is possible if the top guys get it.

As opposed to industry sectors which believe in rapid turnover of CEOs who don’t stay around long enough to care about longer term plans.

Makes me think the ‘high reliability’ thinkers got it right about commitment.

How much real improvement on Asset Management is possible unless there is long-time leadership that cares?

I always taught that the international standard ISO 55000 was a milestone achievement for the profession of Asset Management when it was published in 2014. A consensus across many sectors and countries, when it’s clear not everyone sees the same things in AM.

It’s really about AM as a quality management system – do what you say, say what you do.

And it does acknowledge the issue of senior management, the decisions makers – the importance of leadership actively supporting the management system.

However, plenty of organisations have not felt a great need to be certified against it, even if it addresses basically sensible management practice.

I want to think about two aspects of this.

First, they don’t need certification because it’s not anything they feel especially held accountable for. A couple of bodies, such as Ofgem the UK power regulator, have considered making it a legal or licence requirement, but have been resisted.

Second, even if it were in some way enforced, it doesn’t address big decisions. Somehow, it doesn’t say anything about how an organisation, or a government, decides to spend millions on an infrastructure project – how to avoid wasting the money, or anything they should do after they have a failed project on their hands. It doesn’t really address budgeting at all.

It’s pitched at middle management processes. Yes, lower asset decisions need to be aligned with overall organisational goals – and in some way signed off by top management.

But about the decisions top management makes itself, not so much.

I am not asking for an amended standard in ISO terms. More something like higher standards in public service (and infrastructure is always a service to communities, even when controlled by commercial companies).

What should we do instead, in addition?

- How to get the organisations themselves to think more carefully about their big, long term decisions – it that possible through internal audit-type mechanisms? (Such as, are they following their own asset strategies and long-term planning and budgeting processes?)

- And how much do we, the public, need more formal mechanisms like third party audits, and tougher regulators, to hold them accountable for how they make the big money infrastructure decisions?

What can we, as Asset Management professionals, as middling managers, do about this?

Recent Comments