From script by Lou Cripps

Infrastructure schemes tend to suffer from optimism bias: assuming everything will work as planned.

Focusing on benefits and forgetting some costs is one reason infrastructure projects tend not to be as good as their business cases.

But there’s a parallel problem with risk and time.

Hofstadter’s Law: It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.*

The UK TV programme Grand Designs comes to mind in relation to projects. It doesn’t seem to matter how many years the programme has been running, or the presumption that people who appear on it will have actually watched previous episodes.

In ambitious projects for houses, there seems to be a McCloud Law at work. People will always plan to be in by Christmas, unless they are expecting a baby (in which case they want to be in just before it is born).

In the UK, that means they are probably rushing to weatherproof the house in November, so they can get to work on the interior. And this in turn means they are invariably dependent on it not raining until the roof and windows are installed.

So the question is, is it likely to rain in the UK in November?

There is a technical corollary to this: that the glass for the windows will be delivered late, in any case. Apparently all builders know this.

*Coined by Douglas Hofstadter in his book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (1979). McCloud after Grand Designs’ presenter Kevin McCloud.

This week my oldest and dearest friend, Bob Ritchie, the Secretary of the PAC, died after a valiant fight against Leukemia. I was able to see him just a few days before he passed on Tuesday last week. His influence on AM was immeasurable, but largely untold.

It was Bob who recognised, 40 years ago, the potential of the work I had done for predicting the likely cost and timing of water and sewer infrastructure renewal to be applied to all major state infrastructure and who convinced the Parliamentary Committee to engage me to do a research project where they had never done one before. He worked with me on all eight reports to Parliament and saw, where I did not, the opportunity of a vaguely defined job vacancy in public works to be converted to, as he put it, ‘anything I wanted’, which I interpreted as the opportunity to spread the AM message Australia-, and indeed, world-, wide.

A few years later he was my major support in developing the International AM Competitions and then again when I started Talking Infrastructure. He was always there, encouraging, supportive. So much he contributed! Yet hardly anyone in the AM community would know his name. True, he featured in ‘The Story of Asset Management‘ as he should, and I am glad I had the opportunity to say Thank You before he died.

Vale Bob Ritchie. 01.02.1942 – 11.03.2025

125348823 | Our History © Jakub Krechowicz | Dreamstime.com

More than a decade ago, Penny Burns set up an AM history group in LinkedIn. Her idea was firstly to collect people’s own stories, of how they came to be involved in Asset Management.

Last year Talking Infrastructure published Penny’s own history, of how she came to create Asset Management in 1984 and her first decade working with it. (The Story of Asset Management.)

From when AM really took off in the 1990s, it’s much harder to collect all the strands, and the stories include many other people. That’s why volume two of the history would look very different.

I am still fascinated by the personal journeys – not least because it brings out what distinguishes AM from other disciplines (why do people leave engineering, for example?)

I also have things when I teach about the wider history, but these really come from the people I have met, that I have happened to meet. And what I remember of what they said twenty or twenty five years ago, that they may not even agree with (or remember in the same way).

And the internet, even with AI, doesn’t cover most of it. We erase it when we rewrite a website, unless we consciously refer to what came before (or look up old sites in an archive project). I cannot find that old LinkedIn group, even though I don’t think anyone actually removed it.

Perhaps it’s natural that some only really think about history, and legacy, as they come to the end of their working lives. When you first meet a topic like Asset Management, you just know it’s there, not where it came from.

But it seems to me that asset managers ought to be interested, because we must have a good sense of time and change to do our jobs. “If you don’t know your history, you don’t know where you’re coming from,” as Bob Marley nearly put it. Understanding what’s happened before is the base material for having any sense of what may happen next, in ideas as well as deterioration curves.

Volume 2 is not yet a project. But Talking Infrastructure is planning longer articles on key topics such as planning and risk, and how to mine SAM newsletter material. Not the final word on anything, probably, but the next word, or part of the picture. A resource that can help us remember.

Watch this site for some more notes on our collective history.

And share your own story and memories of how it evolved for you.

From script by Lou Cripps

The lifecycle-based Asset Management Plan was Penny’s solution to the issue of short-term thinking.

In particular, she wanted us all to look ahead at budget requirements for renewals – replacements and refurbishments of aging assets.

But planning and lifecycle thinking are needed for other challenges, too.

For me, the fundamental point is the importance of thinking ahead. Of being proactive rather than reactive, of exploiting what we already know about our assets to stop being surprised by things we can work out ahead of time.

In a week when many of us are trying not to think about WW3, we know we don’t know everything about the future. But we need to make better use of what we do know.

The problem, 40 years on, is that so many organisations don’t.

Here are just some of the questions I would wish – fairy godmother style – everyone to be able to give better answers to.

- 101, if we think we need to build some new infrastructure asset, what will it cost to maintain and operate it?

- What are the different realistic solution options – and what opportunities will we lose in choosing any of them?

- What’s the evidence that we have understood the problem and scoped our preferred option correctly? What else has to be considered in with the capital cost – like the cost of new facilities when we buy new electric fleet, for example?

- What costs and disbenefits should we also cost into the materials we choose, such as embodied carbon or damage to other communities?

- What costs and disbenefits will continue long after the physical asset is gone (think the loss of species or habitats, long-term damage to communities)?

- Do we really have any fact basis for the costs, risks and benefits of something new, as opposed to sustaining what we have?

All of these are elements of whole life cost modelling. Too bad many organisations still don’t even use basic lifecycle costs for their budgeting or strategies.

The underlying problem… is a system that doesn’t plan for the future. Is it lack of the right skills in the right place, or vested interests? Laziness??

One thing I am pretty sure is that it isn’t a lack of available information.

What do you think: just how bad, on a scale of 1 to 10, are our current infrastructure business cases?

Further good reading: Penny’s Infrastructure: we can afford to buy it, can we afford to keep it? Louise Hart, Procuring Successful Mega-Projects: How to Establish Major Government Contracts Without Ending up in Court. Joseph Berechman, The Infrastructure We Ride On: Decision Making in Transportation Investment.

If Asset Management is to deliver better asset planning, we have a challenge. Are we living up to it?

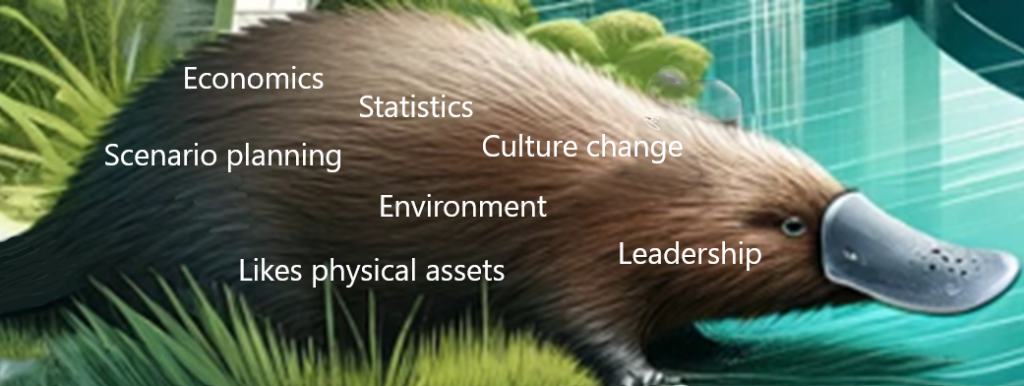

The most obvious thing about AM is that it’s about physical assets. And for most of its history, the assumption has been that the main quality of an asset manager is that they need a background in those areas most concerned with physical assets: that is, engineering, operations, or maintenance.

Who else knows or cares about physical assets? And without that interest, AM might be unmoored: a branch of finance or corporate planning that simply doesn’t know or care enough.

The dilemma is that we need other skills that don’t come for free with delivery backgrounds.

Worse, we need perspectives that definitely go against what we learn in engineering school, or the motivation of operations.

- How do we nurture a profession of people who really like the realities of physical assets but think in a new way about them?

- How early do we need to reach potential asset managers?

There are some good signs – Dr Monica Beedles’ Street Smarts and Biz Smarts, for example, and the Canadian Network of Asset Managers (CNAM) work on AM competences. (And shout out to pioneers of new ways of getting to undergraduates – hello, Valerie Marcolengo!)

But, as CNAM points out, we have a chronic shortage of asset managers.

And many who struggle in post without the tools of effective asset management planning.

How do we reach those with the environmental, analytical, process, culture change and bigger picture skills we need?

What is your ideal undergraduate syllabus to grow the next generation of asset managers?

Thanks to the British Columbia South Island AM Community of Practice for the opportunity to discuss competences this week!

From script by Lou Cripps

What’s the responsibility of Asset Management? In my mind, there’s no question.

The output from an effective Asset Management system is a better allocation of resources to physical assets. It’s all about allocating $ and people where they are most needed, and not to spend or do where that is not needed.

And that can mean only one thing. AM – the system, not the team – should be the major input to the budgeting process for asset-intensive sectors such as power. And a major input wherever there is a significant amount of budget at stake.

The Asset Management input to the budgeting process is what Penny originally called the AMP. Given that ISO 55000 didn’t quite get it, I wonder if we should now spell it out – the asset management planning process (AMPP). One integrated, co-ordinated process that looks across the whole asset base with consistent principles on which to base decisions about priorities for the medium and long term.

We should expect – hope, indeed! – that this will over time have a major impact on business budgeting. That asset-related budgets will change significantly when we have a more optimising system, to make better use of information and plan further into the future.

The focus is not individual decisions, but the wider decision processes.

- What are the priorities for asset renewals, that is major work to replace or refurbish assets?

- What is the appropriate level of planned maintenance to optimise cost, risk and performance?

- Given the current state of the asset base, what is a realistic level of allocation to reactive work going forward?

- How do any growth or new assets fit within the overall strategy (and how important are they in relation to sustaining the assets/ services we already have)?

And this is not planning just about the physical assets. Both the money and the resources have to be considered: there is little point in arguing for money if there is not also a realistic plan for the people to deliver the work.

If we agree this is what Asset Management has to deliver, that also tells us what the main job of a dedicated AM function is and its key relationships with other functions. We can work through what kind of skills and capabilities we require, and where AM sits in the organisation.

It’s why I don’t consider Asset Management in any sense a sub-branch of Engineering – or the capabilities what we teach on current engineering degrees. It’s also not Finance, or HR, or Procurement, though it involves all of these.

And the bigger the amount of dollars at stake, the more vital that we do good Asset Management.

Talking Infrastructure is looking again at the AMP and the asset planning we require for future-friendly infrastructure. If you would like to be involved, contact us!

44169003 © Shea R Oliver | Dreamstime.com

Regulation can be an admission of failure – failure of a sector to do what it should do.

And the realisation that many organisations only take Asset Management seriously because some branch of government tells them they must can seem like our failure, failure to convince them AM is for their own benefit.

And some stop doing it when they are no longer pushed…

What incentivises someone in a position of some power in a public agency to do the right thing? More particularly, what encourages them to think longer term?

CEOs and other senior managers have several kinds of short-term incentives: personal annual targets and maybe bonuses. Local politicians with their own short-term ambitions for re-election. Immediate approval or disapproval from their communities.

Public-sector managers can pick up assumptions about their careers from the private sector. Moving onward and upward by moving organisations – or moving on before anything catches up with you.

On the other hand, whatever their views on their own careers, people in government regulations are normally set the objective of improving the efficiency and effectiveness of what they are regulating over time.

Of course there are poor regulations, and poor regulators. One urgent concern is governments depriving regulators of teeth and funding to enforce the regulations – the UK Environmental Agency’s ability to enforce the law on sewage releases into rivers, for example.

But overall, their incentives are far more aligned to longer-term Asset Management than the average manager. They realise they can’t change things overnight, that it’s about processes and competences and a longer-term perspective. The regulators I have known are generally firm, but patient. They know they have to be.

Infrastructure is too important to be left to ambitious executives alone.

Are we working closely enough with the regulators?

From script by Lou Cripps

Sometimes, it feels too much to do it all step by step.

Most organisations I work with don’t yet have any asset plans beyond five years. Some still only have annual budgets. How do you add in changing requirements for the longer term if you don’t even ask past five years?

And how many years ago did asset managers realise you can’t plan if you don’t think about where you want to get to? (At least 20, because strategy comes before planning in BSI PAS-55 published in in 2004.) But almost no-one has properly strategic ‘asset strategies’. They literally don’t know where they want to take their assets.

Bit by bit – and maybe getting nowhere fast.

But there is an alternative, maybe. Can we describe a compelling vision of where we want to be, first?

Can we even leapfrog some of the gradualist things we currently do?

Gradualism may be personal preference, or professional training. We haven’t always been bold about our mission. Some of us are detail people.

How would it be if we really believed we have a duty of care to make a big difference to the, frankly, fairly dumb way we’ve conventionally managed infrastructure?

Todd Shepherd and Julie DeYoung describe this as a system thing. What we have is a system, or paradigm, which resists change – so tinkering at the edges doesn’t work, because the old system will just bounce back as soon as you stop pushing.

This is, of course, quite a different concept of ‘system’ from the parts and pieces idea of a ‘quality management’ approach such as ISO 55000, which instead encourages a bit by bit, start with AM policy or SAMP. Better than thinking the first step has to be IT – but possibly no more ‘sticky’.

Quicker, and less heartache, to go for undermining the whole thing with strategy and long-term planning from the start?

from script by Lou Cripps

Just a thought about current Asset Management practice.

One core tool used by many is the maturity assessment or gap analysis. See, for example, the Institute of Asset Management’s SAM+ tool.

The concept here is to audit an organisation against a standard, recognise its shortfalls against that standard, and recommend actions to close the gaps – in an implementation plan often referred to as the Asset Management roadmap. The standard could be ISO 55000 series, or perhaps more usefully the 39/now 40 subjects in the GFMAM Asset Management Landscape.

ISO 55000 has some oddities (don’t get me started here on the terms ‘SAMP’ and ‘asset management plans’), but the involvement of far more people in the revision in 2024 probably makes its coverage more realistic.

The problem with the world of AM assessments and roadmaps isn’t fundamentally which topics we assess.

It’s that we simply don’t take our own principles seriously.

Alignment with organisational objectives is surely the key organising concept in ISO 55000. And yet we still propose AM implementation against standards – rather than our corporate priorities.

We also have a history collectively of ridiculous outputs, roadmaps that detail 70 or 130 different actions, for AM teams of perhaps 2 or 3 people to implement in the next 2 years – as though we had no experience, no common sense of what it’s like to implement major change. Almost as though we aren’t taking the AM Landscape ‘red box’ Organisation & People into account at all.

In Asset Management, there isn’t a ‘right’ way to do everything. That’s engineer talk. The optimal way forward is the best realistic option for us, for where we are now, for what our organisations are trying to achieve.

Sure, there are some things which are probably always a bad idea to do, and some that are usually good. But it’s not about a set of rules. Not a template we can fill in, leaving our brains in a jar somewhere.

Whatever we call it, a top-level strategy for Asset Management is essential. But it only makes any sense as a case for how AM will contribute to our organisational targets and challenges. And the practical actions that will do most to support the overall business strategy.

Yeah, the answer is almost always going to be a better planning process for our assets.

But if we start by taking something from inside AM, like ISO 55000 or GFMAM 40 Subjects, and use that as a basis to propose priorities for implementation, we are doing what asset people have too often done before.

Ignoring the business priorities. Not being aligned, right from the start.

Instead, the first thing is to make sure we really understand the organisational challenges, by talking with the people at the top. They won’t always be crystal clear, but that’s the right terrain to start with. Perhaps we’ll even be able to assist in articulating the challenges.

Then talk about what we can realistically do with AM to meet them.*

The gap assessment we require is the gap between what AM could usefully do for our organisation and what we are actually achieving at the moment.

*In my mind, there is very little chance that the corporate priorities for infrastructure won’t require good Asset Management, urgently. We are definitely not at risk of talking ourselves out of a job.

From script by Lou Cripps

Bad news for techies, but infrastructure is mostly money, business and politics.

Yes, Asset Management is about making better decisions on our physical assets. But not just any decisions: the wider, longer-term, strategy and co-ordination that organisations struggle with.

Operations already take care of immediate responses. Engineers are more than happy to focus on the technical details. Finance counts the money – but struggles to do more because it doesn’t get the honest information about the assets that it needs.

The gap that Penny Burns identified in 1984 was, first of all, planning for capital renewals to maintain the infrastructure base we already have, beyond the next year. A need most people didn’t even notice, let alone take on to fill.

In the forty years since, Penny has talked extensively about decisions for new infrastructure as well. About how the overall system needs to change to meet changing demands for service. And the impact of physical assets on the economy, the environment, our communities.

In other words, Strategic Asset Management.

In the past few years I have been asked to develop webinars and other support for better asset strategy and planning. My fundamental message is A. Strategy and planning are not the same, and B. they are complementary, and we need them both.

Over the next few weeks, we’d like to explore them both further. Starting with understanding why organisations are so bad at them.

- Asset Management planning is about the allocation of budget and resources. It therefore has plenty of opponents who only care that their own projects and assets get the money.

- Asset Management strategy requires standing back to think strategically, which many people (including CEOs) are not good at doing.

- There isn’t a formula, or a template. There are good questions, but some of them are hard, and many of them require saying no to some things, and some people. Not going along with the political clamour for simplistic solutions.

- There are vested interests – some of it bordering on corruption (who will make money from this decision?) And more who feel challenged on how they have done things in the past. Even on what they were trained to do.

What are your experiences of asset planning? What works – and what gets in the way?

Is any of it really a technical problem we can solve at our desks?

Recent Comments