In the art world, knowing the provenance, or the ownership history, of a piece of art, is critical to establishing its veracity and value. The same should be true of any ‘fact’ that you wish to use to support an argument in asset management. We speak of ‘evidence-based’ decision making, but how valid or reliable is our ‘evidence’? In other words, how do facts become facts? As you think about this, consider the following:

I had been asked to review a paper about disability access and the author was keen to get my comment. As I read it, I noted his use of substantial and very favourable benefit-cost figures. Knowing how difficult it is even to conceptualise some of the benefits, let alone measure them, and finding no explanation of the figures in his paper, I ask him for the source.

“Oh, never mind that”, he airily replied, “what do you think of the paper overall?

I told him that I wouldn’t be able venture an opinion until I understood the data and, after a fair amount of applied pressure on my part, he eventually said:

“Look, I made them up! But it doesn’t matter because I am giving this paper at an international conference and someone will quote me, and then someone will quote that person – and pretty soon, it will be fact!” Unfortunately, this is a true story and he may not the only one acting in this manner.

Much of the time, however, mis-representation is not as blatant as this. It can be simply a matter of not paying enough attention to labelling the axes. Often we slap up a graph without identifying the axes and expect the audience to fill in the gaps from the context of the conversation. This is a lazy habit that is responsible for many subsequent misunderstandings. For example, what we think is a trend line showing full life cycle costs, might simply be a trend of operating costs. With very different implications!

What other examples do you have where presentations or papers, have or can be, misinterpreted with ill effects on Asset Management?

Ten years ago, after 20 years, I brought SAM to a close. I asked past contributors what the key issues then were, and what we – as asset managers – should do. What did they say – and what would you say today?

Here is that issue, SAM 400. What are your favourites? Top of the list for me was Melinda Hodkiewizc, Professor of Engineering at the University of Western Australia, who bluntly stated it was time to ante up and provide evidence to support our claims for asset management. I could not agree more, but have we done it?

Several referred to the need to make things simpler – both in terms of action and communication and Peter Way, then Chairman of the IPWEA, while recognising the difficulty, spoke of the critical need for asset managers to speak out whenever they see their political masters moving in a questionable direction. If only! After all, if we who know don’t do it, who can?

Many recognised the importance of the quality of our people in AM and the need for us to continue to think and to develop our abiliies, not mindlessly react. The ever practical Ashay Prabhu, implored us to ‘stop measuring the gap and start plugging it’.

While most focused on developed countries, Jo Parker, the only engineer I know who has had to build a bridge under duress with limited resources – whilst wearing a burka! – argued that “To spread AM to developing countries, first understand their world!” Is it ignorance or arrogance that drives so many ‘advisors’ from developed countries to assume what works for us will work everywhere?

What were the key issues then? Alan Butler, then Director of the Australian Center of Value Management, now retired, identified the following:

- depletion of core skills and the resultant dumbing down of the asset portfolio “clients” who need to be responsible for effective briefing and critical review of solutions being delivered on their behalf – the asset client must remain an informed client;

- the politicising of the public service where whole agencies are wrapped up in the short term priorities of the incumbent colour of government at the expense of strategic, portfolio-wide context – impartial advice, without fear or favour must exist;

- changing the procurement models that place specialist consultants in a position of technical influence where smaller solutions or non-build solutions are not in their commercial interest to present to the engaging “client” – no matter whether the arrangement is called an Alliance, Strategic partnership, Design & Construct, the “non-asset” or smaller solution must always be sought and tabled for real consideration;

- not understanding what “value for money” means for each client – these words are written everywhere including White Papers, policy, business cases and project briefs with very little understanding or ability to explain, measure or demonstrate what levels are sought and achieved – We have the tools and institutions to address this.

I think that this was a pretty good list for the time. What are the most critical issues we should now address? Thoughts?

Me at my favourite coffee shop

Most mornings I have coffee in my favourite coffee shop and have a chat with George, the barrista. I like George and I want his coffee shop to remain viable – difficult in these times of rising prices – so, in addition to the pleasure of the coffee itself, I get satisfaction from knowing that I am contributing in a small way to his continuing income. I could have spent my $6 in another coffee shop or not on coffee at all and then those dollars would contribute to someone else’s income and job sustainability so I know that my expenditure is not increasing the number of jobs in total, I am simply impacting (admittedly in a very small way) where the jobs are being created or preserved.

But let us consider this same type of transaction – purchasing something for money – on a far larger scale. The government decides to build more infrastructure, say for a billion dollars, and it justifies that expenditure on the grounds that it is ‘creating thousands of jobs’. Let us set aside for a moment that the number of jobs is usually greatly exaggerated, never validated, and many of them may last only a few weeks or months. The real question is: are these jobs ‘additional jobs’, which is the way we are expected to view it and generally do, or have we simply changed the type and location of the jobs?

The government could have spent that one billion on community services (doctors, nurses, teachers, police etc or, indeed – if infrastructure is so important – on the maintenance of existing infrastructure ), or it could have left it in your pay packet instead of raising taxes to fund its infrastructure spend, but it chose to spend it on bricks and mortar. We like the idea of ‘more’ jobs being provided. We are less thrilled about the idea of jobs being lost. Fortunately for our peace of mind we do not see the jobs that are lost and although we do experience the lack of services that results we do not necessarily associate the two. So let us look at a typical project.

In December 1985 when the Adelaide Casino was established by the state owned Lotteries Commission, there was much hype about how many jobs would be ‘created’ by the Casino. And indeed, for the first six months, there was great excitement about this novelty. People flocked to it, abandoning their usual venues. It was the first Casino in the state and many went there to drink or eat, and some to gamble and the Casino employed many. After a while, however, the novelty wore off, fewer people went and the number of service people employed by the Casino declined. Customers sought to return to their previous venues but some of these, having to cope with reduced incomes in the interim but still pay high city rental prices had gone broke and moved out. Trouble was, in calculating the increase in jobs, no attention had been paid to where the new Casino customers were coming from or how long they would remain customers. The lovely little coffee shop I frequented in the city, which provided chess sets and boards for its customers, was sadly one of those that went out of business.

The moral of this story is when thousands of new job are vaunted, stop, look closer.

My team makes use of premortem thinking: as part of planning action, immediate or long term, consider how it might go wrong. We think ourselves into the future looking back at a project (or a meeting). Humans are surprisingly good at this time-travelling.

For me, this is part of a principle Asset Managers should embrace: the principle of reversibility. It’s not just about understanding the consequences of our decisions, but also about planning for the ability to undo or reverse their effects if needed. Sure, you can’t un-ring a bell, but we can find ways to get as close as possible to the pre-action state and minimize the impact if we think about it right from the start.

Do our plans have exit strategies or an undo button? None that I have seen, why not?

This is especially crucial in infrastructure projects, where large investments and long lifespans magnify the potential impacts. How would they be delivered differently if that was required? Would that requirement cause us to better maintain the infrastructure we currently have? I think so.

Let’s face the hard questions: Can we put rare earth metals back in the ground? Can we undo the energy consumed in building something new?

By embracing the principle in Asset Management and infrastructure decision-making, we can strive for resilient and adaptive systems that serve the present while safeguarding the future of generations to come. We navigate challenges with eyes wide open.

We ask tough questions, anticipate consequences, and face the answers with truth – and then we create our plans and strategies.

In case you haven’t caught up with it yet, ALGA’s ‘2024 National State of the Assets Report: future proofing our communities’ was released a week ago. You can download a copy of the Summary and Technical reports here:

Sometimes reviewing a report is a chore. This was a pleasure. It ticked all the boxes: it was very readable; honed in on the important issues and provided useful, verified data. It would be impossible for anyone to read this report and not gain a great appreciation for the pressures being faced by all councils, but especially smaller and regional councils, as they face the combined effect of asset ageing, climate change, increasing consumer expectations and more stringent regulations – and very little access to funding.

My overwhelming reaction, and it may be yours too, was to realise that better asset management is unlikely, by itself, to be sufficient. And this may be the most important take away. Asset Management is often presented as a panacea, it is not – but it is where we must start, for if we cannot manage effectively what we already have, how can we ask for more?

The good news is that this ALGA report indicates improvements are being made. How we express data has a major effect on how it is received. I particularly appreciated having infrastructure costs expressed per ratepayer. There was a time when we felt that large aggegate numbers had more impact and everybody tried to make their future costs as big as possible ‘to be impressive’, but expressing costs on a small personal scale, i.e. per ratepayer, enables greater understanding. We are more able to feel it. I also like the way that averages were dealt with. When I started work on life cycle renewal costs, realising that averages concealed more than they revealed, I put a lot of effort into calculating full age distributions. But ALGA has realised we don’t need to do all that work if we supplement the average with an indication of the extent of the most urgent of renewals. Very sensible. Indeed the entire report is very sensible. There is a lot of data, but it is carefully designed not to overwhelm.

It is a useful base for arguing for change. Change in the way we fund councils, change in the way we record and use depreciation figures are the first two that come to mind. What else would you like to see changed?

Penny and Ruth at AM Peak gala dinner, April 16 2024

Since I last posted I have spent a month celebrating 40 years of Asset Management in Australia with Penny, Jeff and Gregory; gone to one of my favourite conferences in Minneapolis; taught an advanced AM course to some sophisticated AM practitioners in Calgary, as well delivering to as a post ISO 55000 certification client in California.

I have been thinking about where AM needs to go next, at the same time as worrying that things have not moved far enough.

And it just keeps coming back to: We Need to Raise our Game. And not because what Penny kicked off four decades ago hasn’t made a huge difference already.

But I want us to do more.

First, to effect what Penny set out to do through Talking Infrastructure: to look up and out, to make a difference to key decisions on what infrastructure we really need.

Secondly, as I start to unwind from delivering basic AM training – something I have loved doing for nearly 14 years now – I reflect on our competencies.

This kicks off a series of questions and reflections on what we want to change, and how to do it.

How to interest existing AM practitioners in upskilling on risk, data analysis, culture/ system change, persuasion, strategic thinking?

How to find people who want to challenge the status quo on infrastructure projects?

What can we best offer from our collective experiences to support better decision-making?

I am looking forward to this!

“ It was great to celebrate Asset Management’s 40th year with many old friends and new, a celebration that started with AM Peak in Adelaide and finished with the IPWC Conference in Melbourne. At both ot these gatherings about 30% of the attendees were women, mostly young women, such a very good sign for the future of AM. Also good signs of ethnic diversity. I recalled the beginning of both associations and so had occasion to reflect on how they have grown and developed over the years.

In between these events I was able to spend time in Brisbane and meet with AM friends and colleagues of #Chris Adam at Stantec and #Joe Mathew at QUT, while enjoying the company of my long time friend #Kerry McGovern. Then it was on to the Blue Mountains to meet #Lis Bastian and to stay with #Jeff Roorda, Infrastructure Director with the BM City Council. This was shortly after a major landslide had caused the collapse of the only road into Megalong Valley. A new temporary road was built within days but was only able to cope with light traffic putting Jeff in the position of dealing with simultaneous environmental, economic and social disasters in this very beautiful and highly sensitive area. Then just a day ago came news of a sink hole in a Sydney suburb, the result of heavy rains and it is likely that many more of us will be dealing with triple disasters soon.

The truth is that across the country we are facing major challenges and major change and much that we think we know now needs serious reconsideration. I am now taking a Sabbatical or “Time Out” for the next six months to research and reflect on what those of us in the Infrastructure and Asset Management game can do, but I am happy to receive your ideas If you are also concerned.

PS. I have today done what I should have done weeks ago and that is to upload all the remaining chapters of Norman Eason’s “Maintenance and Asset Management Information Systems“. Now this link will get you the lot! Do have a look. I am sure that you will be surprised by how much you can still learn from work that was written 25 years ago! Then the idea was to develop understanding so we tackled the ‘why’ of different issues. Today the emphasis has been on the ‘how’. But the ‘Why’ is still critically important – because likely different .

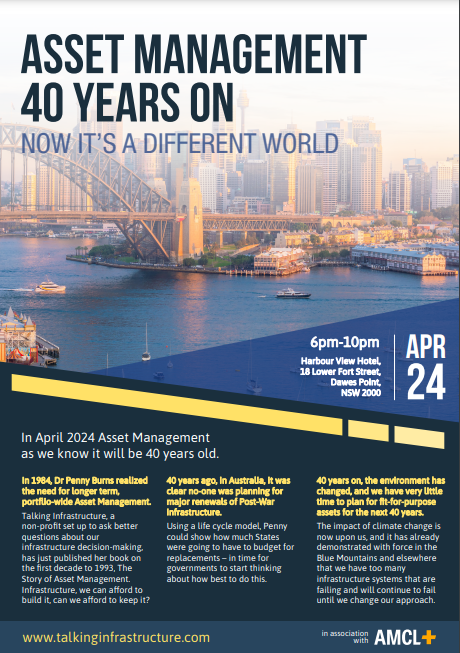

Come and meet Penny and Talking Infrastructure in person! Watch this space for additional details, but here’s the programme so far:

April 15 & 16 AMPeak, Adelaide. Penny and Ruth will be at AMPeak.

April 18, Stantec, Brisbane

April 19, PACoG, Brisbane. Asset Institute, QUT, 11am- 12.30, followed by lunch. Join Joe Mathew and Kerry McGivern along with Penny and Ruth to discuss what we’ve learnt in 40 years – and look forward to the next 40. Includes a look of what is happening with asset management internationally, in this big year for AM.

April 23, Blue Mountains City Council, Katoomba, 10am to noon. Seminar with Jeff Roorda on Blue Mountains City Council planetary health and disaster recovery experience, plus update on the new advocacy project underway by IPWEA Roads and Transport Directorate (IPWEA RTD – NSW/ACT), on Lessons Learned from Disaster Recovery, to assist NSW Councils work with Local, Strate and Federal Government Agencies.

April 24, Sydney event, Dawes Point. 6-10pm Harbour View Hotel, 18 Lower Fort Street, Dawes Point, NSW 2000. Using the recent experiences of the Blue Mountains City Council, Talking Infrastructure is holding an event in central Sydney to call for urgent changes in all of our asset mindsets and tools to ensure planetary health, biodiversity and climate change resilience. Meet with Penny, Jeff, Gregory and Ruth, plus local IPWEA. Food provided thanks to AMCL.

April 30, IPWE, Melbourne. Presentation by Penny. Penny and Ruth will be at IPWE until May 3. There will also be a dinner out in Melbourne for TI friends and colleagues – please let us know if you would like to join us. And bring along your copy of Penny’s book to get signed!

If you are planning to attend our Sydney celebration, please RSVP to: amis40@talkinginfrastructure.com so we can keep an eye on numbers – limited to the first 60! Event is free, includes food and discussion with Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda and a whole heap of old friends and colleagues.

Full update of the 40th year celebration events shortly!

Join us at the Harbour View Hotel in the Rocks and help celebrate with finger food and drinks – plus Penny and Jeff on what we have learnt from the last 40 years to help us meet the challenges of the next 40.

Many thanks to Richard Edwards, Lynn Furniss and Matt Miles of AMCL

Recent Comments