In the sharing economy (Uber, Airbnb) participants either earn income from assets that would otherwise be lying idle or benefit from access to assets that they only need for a short while. Now, what started with consumer services, is moving to business. Why own your own combine harvester when you can rent? These transactions are more complicated but possible.

In the sharing economy (Uber, Airbnb) participants either earn income from assets that would otherwise be lying idle or benefit from access to assets that they only need for a short while. Now, what started with consumer services, is moving to business. Why own your own combine harvester when you can rent? These transactions are more complicated but possible.

‘Where can we go from here?’

New possibilities arise when we combine the benefits of the sharing economy with the new technological possibilities of blockchain. For a really simple explanation of what block chain is and how it may change our future, you might want to start here (Hint: it is more than bitcoin)

Once you have read this (or if you are already au fait with block chain) then you may wish to explore how the NSW Government is putting digital driving licences on a blockchain.

Now let’s move on. In my last post I suggested that the vexed problem of transparency might be solved by a combination of our new technologies.

I can see the technology in use within our cities and rural communities underpinning local energy generation, shared facility use between commercial and community groups and significant opportunity for formal Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) where the use and consumption of the asset is clearly demarcated by micro-transactions, allowing real-time transparency.

While the technologies are being developed, the underlying elements of Blockchain and IoT are now firmly in place, the technology is not new, but finding its niche. Much like the development of laser technology.

The future will be determined by the success of these trials, and the adoption of micro-transactions by our government and institutions. Initial trials in Australia and Internationally show reason for optimism that this may be a solution for sustainable funding for many of our shared resources. Perhaps an opportunity for citizens to become “owners†of assets like bridges and tunnels, with charges being apportioned to use with greater accuracy and equity and transparency.

What do you think the future holds?

Transparency of government is the greatest tool we have for ensuring the best decisions are made by officials and functionaries and reducing corruption and poor decision making.

Legislation, guidelines and reviews surrounding Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) abound as we collectively try to find a way for government to utilise private efficiency and expertise without exposing the public to risks associated with corruption of officials and contracts that serve the private rather than public partner.

The problem with many PPPs and government business, are poorly constructed contracts. Inappropriate measures, guarantees of returns and unclear maintenance and renewal responsibilities.

In the past it has been difficult for us to measure the use of infrastructure by different groups, the consumption / degradation of infrastructure, the degree of maintenance and renewal required and applied to infrastructure.

This has lead to simplistic drafting of contracts based on unsupported estimates.

Enter micro-transactions and Internet of Things.

We now have the unprecedented ability to measure almost everything, and cheaply. We have technology that allows us to make the recording of these measurements publicly available and immutable, and we have people writing clever contracts based on micro-transactions.

By combining these things there is opportunity for us to include all aspects of infrastructure in government contracts for PPPs. Reward can flow to the Private Partner based on utilisation, maintenance, renewal of the infrastructure as well as other measurable impacts, such as improvement of performance of the infrastructure, or lessening of burdens on society and the environment.

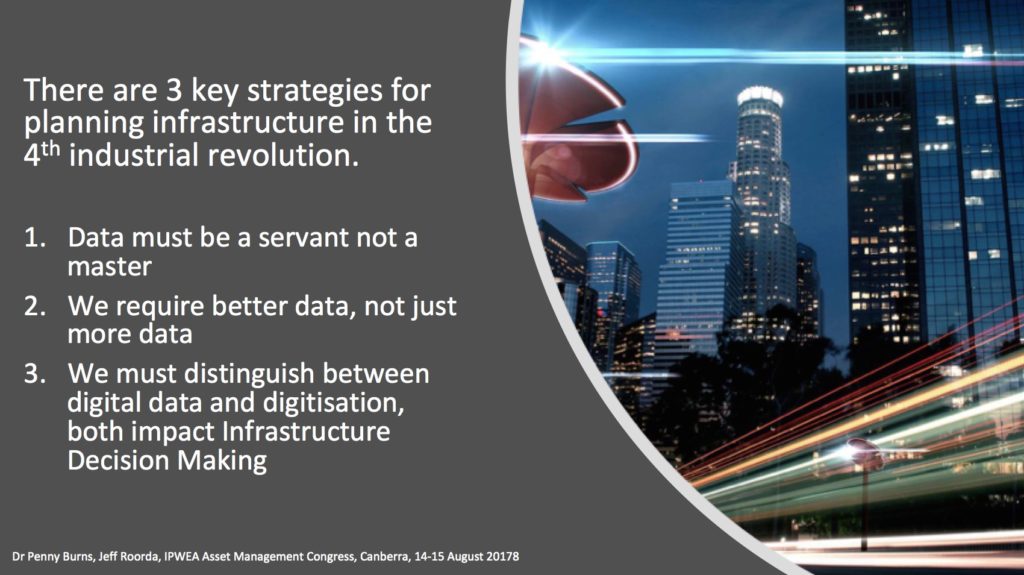

The possibilities of big data are impressive but let us not get carried away.

Not only is there the danger of trusting in the results of data manipulation that we do not understand (cf the many studies showing the dangers of ‘private’ algorithms that are not open to analysis), but there is the greater danger that we put our faith in aiming at ‘data’ outcomes (e.g. KPIs) rather than people outcomes.

So let us put our effort into better measurements of what really matters – better (i.e. more relevant) data. This will inevitably mean using non-dollar measures – and judgement.

Discussion today tends to conflate the benefits of greater use of digital data and digitisation itself. Both are valuable, and both impact infrastructure decision making, but they are not the same.

There is currently much discussion of loss of work opportunities through the use of robots. If our decisions are driven purely by data, then robots can do a great job. But if we want our decisions to include values such as kindness, compassion, and fairness, then we need people.

We appreciate the benefits of big data but do we really want to live in a world without kindness, compassion and fairness?

Infrastructure spending is often justified on the grounds that we are ‘building for the future’. If we truly believe this, and if we are concerned to provide a safe and prosperous world for our children to inherit, then we are running out of time. This is the conclusion of “No Time for Games: Climate Change and Children’s Health’ by Doctors for the Environment Australia where they describe the many ways in which periods of excessive heat, disease carrying flood waters, storm events and rising sea levels are seriously impacting the physical and mental well being of our children. This is not a hypothetical. It is happening now. And the recent NEG decision to support coal under the guise of providing ‘reliability’ for renewables is, unfortunately, symptomatic of the hypocrisy of the time.

Infrastructure spending is often justified on the grounds that we are ‘building for the future’. If we truly believe this, and if we are concerned to provide a safe and prosperous world for our children to inherit, then we are running out of time. This is the conclusion of “No Time for Games: Climate Change and Children’s Health’ by Doctors for the Environment Australia where they describe the many ways in which periods of excessive heat, disease carrying flood waters, storm events and rising sea levels are seriously impacting the physical and mental well being of our children. This is not a hypothetical. It is happening now. And the recent NEG decision to support coal under the guise of providing ‘reliability’ for renewables is, unfortunately, symptomatic of the hypocrisy of the time.

We can regret the loss of leadership as David Shearman did in his excellent article in the ABC Adelaide news this morning “Climate change is World War III, and we are leaderless” and urge our elected members to do more, and we should do this.

But maybe we need to DO more? Maybe in our leaderless world we need to take leadership into our own hands? In the past we have tended to leave large scale infrastructure decisions to others. Perhaps this now needs to change? No Time for Games has this to say about Infrastructure:-

Infrastructure and risk reduction

‘Protecting children’s health also requires risk reduction in sectors other than health such as housing, agriculture, urban planning and transportation. Improvement in urban and regional planning design such as relocation away from areas at risk from natural disasters or sea-level rise, or better housing design to reduce heat impacts, are examples of reducing the risk of climate health impacts to children.

‘Protecting children’s health also requires risk reduction in sectors other than health such as housing, agriculture, urban planning and transportation. Improvement in urban and regional planning design such as relocation away from areas at risk from natural disasters or sea-level rise, or better housing design to reduce heat impacts, are examples of reducing the risk of climate health impacts to children.

Reducing socioeconomic disadvantage in children and improving baseline health, food security and education are fundamentally the best form of climate change adaptation due to their role in making children and families more resilient and better prepared for the environmental risks brought by climate change’

We can all have a say in promoting these changes, directly where we are able, and in voting for measures which improve them and against those which don’t.

That the increasing health effects of climate change disproportionally affect children challenges the most fundamental call of humanity, to nurture its young.

Failure to act is a major intergenerational injustice

My thanks to Ian Spangler for drawing my attention to this.

When computerisation first appeared on a large scale, we eagerly adopted it – and used it to carry out the same processes we had used bc (before computerisation). It was many years, in some cases, decades, before we realised that the real value of computerisation was to adopt completely new processes for new outcomes. Today the power of digitisation for connection is still being recognised. We eagerly embrace ‘smart technology’ in our cities – but are slower to recognise that connection can be used to bypass the city. That is we are increasingly able to ‘live, work and play’ in the suburbs, or the country, improving our lifestyle opportunities and reducing environmental costs. But first we have to see it.

INFRASTRUCTURE DECISION MAKING (IDM) IN PICTURES

DON’T MISS ANY OF THIS NEW AND IRREGULAR SERIES, JOIN THE TALKING INFRASTRUCTURE COMMUNITY (it’s free) AND RECEIVE OUR FORTNIGHTLY NEWSLETTER TO KEEP YOU UP TO DATE

There was a time when I would be in and out of an art gallery in 30 minutes, bored. I looked, but did not engage. Then at a Picasso Exhibition, i found paintings that I really liked, but also many that turned me off completely. After viewing all, I went back and studied these two groups and asked Why? Now galleries are no longer boring. I apply the same process to conference talks. I note all the new ideas, the new linkages that really please me and write them down so that I can think more about them later, and I also note those statements that drive me nuts, and I think about these as well. No prizes for guessing what category the ‘heretical questions’ in the last post fell into.

There was a time when I would be in and out of an art gallery in 30 minutes, bored. I looked, but did not engage. Then at a Picasso Exhibition, i found paintings that I really liked, but also many that turned me off completely. After viewing all, I went back and studied these two groups and asked Why? Now galleries are no longer boring. I apply the same process to conference talks. I note all the new ideas, the new linkages that really please me and write them down so that I can think more about them later, and I also note those statements that drive me nuts, and I think about these as well. No prizes for guessing what category the ‘heretical questions’ in the last post fell into.

But the IPWEA Congress this week, ‘Communities For the Future, Infrastructure for the Next Generation’ was far richer in yielding good new ideas, thoughtful linkages, and new ways of expressing accepted ideas so that they come to life and are taken out of the realm of platitudes. These deserve a far wider coverage, and so, with the support of our podcast partner, the IPWEA, we will be bringing you these ideas, and many others, in our forthcoming podcast series. Watch for it!

Or better still, join the Talking Infrastructure Community (click here) (its free!) and you will be the first to know when we launch.

A closing note: At an after lunch session in Parliament House many years ago, the talk was so boring I found it a hard job to keep my eyes open. Yet my colleague was riveted! He was listening intently and taking notes. At the end I sighed and said ‘That was a really boring talk’. ‘Absolutely’, he agreed. Surprised I responded ‘But you were riveted, paying great attention, taking notes, how come?’

His reply? ‘To make so boring a presentation, there must be many things he was doing wrong. I just wanted to figure out what they all were!’ Be engaged!

A heresy is a belief or opinion contrary to the orthodox (usually for religion, but applicable more generally) Here are some heretical questions in the asset management/infrastructure decision making field.

A heresy is a belief or opinion contrary to the orthodox (usually for religion, but applicable more generally) Here are some heretical questions in the asset management/infrastructure decision making field.

Heretical Question 1. Spend better or spend faster? An economist speaking at the IPWEA Congress in Canberra recently, argued that a greater spend on infrastructure was better ‘performance’. But is it? Jeff Kennett, former Victorian Premier, complained that 26% of funding allocated for capital construction had not been spent. He blamed over cautious bureaucrats. Both are focused on the size of the spend – and not what the money is being spent on. Is this really in the community interest? Or is this attitude (not confined to Australia) a contributing factor to the increasing evidence that infrastructure funds are poorly planned and many demonstrably lacking in justification? (cf Joseph Berechman ‘The Infrastructure we Ride On’ 2018)

Heretical Question 2. What is the purpose of infrastructure? And what should it be? Wearing our ‘better angels’ halo we say we are building for the future, but is this really true? If we were, would we not have a well developed vision of the future that we wished to create, and an infrastructure decision process that enabled us to plan to achieve it – and to adapt those plans as changes occur? Where is that vision? Where are those decision processes?

Heretical Question 3. The pipeline. An economist spoke of waves of capital expenditure and was concerned at the lack of a pipeline of projects that would maintain construction activity in the near future. Another speaker commented to the effect that Australia should ‘prioritise infrastructure’. But should it? Why? A pipeline of construction projects will ensure work in the construction industry. But the construction industry represents only about 10% of total employment. Why should we spend massive amounts of capital to ensure the jobs to privilege such a small section of the economy?

Heretical Question 4. Multipliers. You might argue that construction expenditure generates much more by way of multipliers – three times as much according to one speaker. Really? Where is the evidence for this? Many people blithely quote figures such as this, but cannot justify them. Construction expenditure does create jobs. ANY expenditure creates jobs. If the people who receive the income go out and spend it, other people benefit. This much makes sense. But how much of a large construction contract goes to the rich who may save rather than spend, and how much of the rest goes to workers who do not know where their next job is going to come from, and thus will tend to save more than spend? Wouldn’t a permanent maintenance job do more good for the economy than a short term construction contract. Or the same amount of money spent on nurses or teachers?

Heretical Question 5. Supply driven infrastructure. Jeff Kennett argued that we would do well to follow up projects with more projects to take advantage of the, now unemployed, workers completing the first job. In other words build infrastructure to provide jobs. Is this sensible? Tasmania in the late 1980s came to grief over this. With little employment in the North, infrastructure projects were created to provide jobs. The projects not only provided work for the unemployed in the north, but they attracted others from around the state so that when the project finished, there was now a bigger pool of unemployed, demanding a bigger project – and so on. Now most of the Tasmanian population is in the South so the infrastructure was largely underutilised. As a result of this expenditure, the state came close to bankruptcy. So, is this really a sensible idea?

Heretical Question 6. Vision/Plan. We have a tendency to use these words interchangeably, but is this sensible and safe? A plan is a set of actions designed to secure a goal or objective. A vision is an idea of some future state that we would like to achieve. Affordable healthcare could be a vision. A set of projects including asset and non-asset solutions could be in a plan. As technology, demographics, environment, governance and public attitudes change and information is acquired, we would have a succession of plans, all adapting to the current circumstances but addressing the vision. The vision may be a 50 year vision (even a 7th generation vision) but we would surely not wish to commit ourselves to a 50 year set of projects conditioned by only what we know now.

Feel free to add your own heretical questions.

Media articles often leave infrastructure questions dangling. QUESTIONS ARISING is an opportunity for those of you who read widely and keep their eye on what is happening to identify these articles and the questions that need to be answered. These can then be addressed in our forthcoming podcast series, so get involved – add your questions to those listed here, suggest possible lines of development, add new media articles along with the questions they raise. Sources may be the daily journals, the web, podcasts, radio, TV. Plenty of scope!

Media articles often leave infrastructure questions dangling. QUESTIONS ARISING is an opportunity for those of you who read widely and keep their eye on what is happening to identify these articles and the questions that need to be answered. These can then be addressed in our forthcoming podcast series, so get involved – add your questions to those listed here, suggest possible lines of development, add new media articles along with the questions they raise. Sources may be the daily journals, the web, podcasts, radio, TV. Plenty of scope!

Here to introduce our first QUESTIONS ARISING are two items identified by our Business Development Manager, Ian Spangler.

1. The Economist’s Intelligence Unit’s recent report on “Preparing for Disruption: technological readiness ranking, 2018”, places Australia in the top ten for the historical priod (2013-2017) BUT it forecasts that in the next five years, Australia, Singapore and Sweden will take over as the top-scoring locations. The ranking is based on the number of mobile phone connections and internet access.

Questions arising.

- Is this enough to ensure technological readiness?

- What else should we be looking at to test readiness?

- Australians, who are not easily overawed by authority, may well joyfully take up the idea of disruption, but to what end?

- How can we tell whethe our innovation is well directed?

- What else? Add your comments below.

2. The small homes project was recently launched in Melbourne. The RACV reports that “from the 1950s, Australia’s average house size more than doubled to 248 square metres at its peak in 2008-09. Then last year something strange happened: the size of new builds dropped. Over the past 20 years, median house prices across the country have gone up by more than 300 per cent while weekly wages have only increased 121 per cent. Rising cost-of-living pressures are also draining our bank accounts, with the average annual energy bill in Victoria now around $1667. Building and running a big house is not cheap and it is not great for the environment.”

Questions arising

- The ability of the demonstration small home to provide so much convenience in such a small space is its use of 4G and 5G connectivity. How do you see this affecting futur constructions?

- Will we continue to reduce the size of our dwellings? If so, what factors may come into play? If not, why not?

- If our dwelling size does decline markedly, what impact might this have on other infrastructure?

- Other Questions

Three great days in Melbourne in which I met with many asset managers for talks over coffee (or the hard stuff).

Three great days in Melbourne in which I met with many asset managers for talks over coffee (or the hard stuff).

The benefits of a podcast series addressing future change and its impact on infrastructure decisions today was readily recognised and the ability of the podcast to draw from the perspectives not only of those who are responsible for the supply of public infrastructure, (decision makers, analysts, managers and advisors) but also those who rely on infrastructure to achieve community and commercial outcomes was seen as something that people wanted to be involved in. Think those who supply and those who rely!

I was able to meet with Anne Gibbs, the current CEO of the Asset Management Council, who has been extremely helpful in providing follow up material, and with Sally Nugent, the former CEO, as well as a number of active AMC members including Andrew Sarah, Greg Williams and Kieran Skelton. I also had a very positive meeting with Jaimie Hicks, Business Development Manager of the Water Services Association, Australia.

Lara Morton-Cox of the Victorian Treasury drew my attention to innovative work they are doing to encourage future thinking to be built into agency asset management plans. It was also a pleasure to catch up with new friends and people I had not seen for some time – Roger Byrne, Claudia Ahern of Creative Victoria, Christopher Dupe now Manager, Capital Works Programs at Museums Victoria, Brenton Marshall, Shellie Watkins, Thomas Kuen of Melbourne Water, Steve Verity of TechOne, Roger Harrop, Ian Godfrey, Gary Rykers, Dr Nazrul Islam, David Francis, and Greg Williams,

On Friday morning I was able to catch up with Robert Hood, who is now working with Asia Development Bank developing asset management expertise and believes that our infrastructure decision making podcast may have relevance to their work. I also met Robert’s wife, Cherry, from Capital Works Planning at the University of Melbourne who had some interesting ideas and we will talk in October about student involvement in our podcasts.

In the afternoon, a magic time with Ashay Prabhu and his fantastic team of energetic, imaginative and committed young people at Assetic. And finally, a leisurely and interesting conversation over wine with Tom Carpenter, trainer and CEO of the Institute of Quality Asset Management.

I will be back in Melbourne mid October, so if you missed out this time, let’s catch up in October.

Recent Comments