SEVEN SPECIFICS OF BEING A STRATEGIST

SEVEN SPECIFICS OF BEING A STRATEGIST

We were talking about asset management – of course! – but more specifically about ‘thinking like a strategist’ when my friend and colleague, Ruth Wallsgrove, asked:

‘What would a strategist do that a professional engineer, accountant, or administrator would not?’

Now the truth is that any professional can think like a strategist, and often does. The trick to doing it better is to do it consistently, consciously, and in collaboration with others, in other words – corporately! So What does it mean to ‘think like a strategist’? Here are what I consider the 7 specifics.

- The Goal – Strategists adopt a big goal, the aims and objectives of the organisation they serve. They recognise that once the prime objective of their organisation is recognised, there may be many different ways to achieve it, in addition to those already identified – and they look!

- The Time Frame – Not ‘now’, and not ‘then’, but rather ‘from now to then’. A focus on what needs to be done to plot the path from the current situation to the desirable future. Such a path needs to be flexible and allow for adjustment as changes occur. (i.e. there is always a Plan B. C…)

- The Scope – the whole organisation and its wider social and environmental context

- The Reason – never ‘because XYZ is doing it’ or ‘because we have always done it this way’ (or even because it is new, innovative and exciting) but because, on balance and considering the options, it is the best way- for now -of achieving the goal. Always reviewing.

- The Attitude – Pragmatic (think Machiavelli), do what works, but analyse why it works. Curious. Sceptical. Analytical. Challenging.

- The Awareness – Strategists are not Superman and do not attempt to be. They know they need, and they fully appreciate, the contribution of others: professionals, tradespeople, users. The stance is one of willing collaboration.

- The Communication – understanding what drives the actions of others is key to the way in which ideas can and should be presented to be effective. People don’t fear change, they fear change being imposed on them. The art of good communication is winning hearts and minds. Strategists listen for more than words, they attune to the emotions of others (feelings of fear, trepidation, courage, hope)

The key difference between the Strategist and Other Professionals can be seen in the goals that they adopt.

Take Backlog for instance. A maintenance engineer will see the need purely in terms of the asset, its reliability and ease of operation. He will generally not see that the resources needed to achieve this reliability and ease of operation that could be used elsewhere in the organisation, and possibly achieve even greater good.

Take KPIs. An accountant may see, and even promote, rules such as debt ratios or productive staff: overheads ratios because these are manageable by her division. She may not even see the damage that is being caused to overall corporate goals by such rules.

Or take “finished staff work”. Any administrator that insists on finished staff work as the sine qua non of excellent administration has to accept old ideas thus ruling out new ones. Easier on him, but not necessarily to the benefit of the organisation.

Each of these is an instance of ‘solo thinking’

Solo thinking is ‘what’s best for me, my performance, my KPI’ – rather than ‘corporate thinking’ or what’s best for the organisation or community.

Organisations bring this upon themselves to a large degree by failing to articulate their goals, and especially their values. They also bring it on themselves by not encouraging and rewarding the strategic behaviour that would serve them better.

Thinking like a strategist, is ‘thinking holistically’ (I realise this word scares the living daylights out of many people, but it really is necessary!)

Professionals can improve their ability to ‘think like a strategist’ by moving ahead in any of these 7 specifics

Of Hammers and Nails

If the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail! But the reverse can also be true as I found this week. If you have a nail you cast around for what can be pressed into service as a hammer (A meat tenderiser works well.)

My philosophical nail is the problem of sound infrastructure decision making and it turns out that, even when I think I am taking time out to relax, the hammer search continues.

1. “13 Minutes to the Moon”

This is a new BBC podcast series that I am listening to that covers the planning and the almost decade-long lead up to the Apollo landing. The ’13 Minutes’ refers to the last 13 minutes before the landing when a number of times problems arose and it very nearly didn’t happen. Although you know the end of the story, the premise behind this podcast is that few of us really know the beginning. It is a documentary style podcast with lots of audio clips from those involved at the time. Good to listen to.

It got me thinking.

JFK’s decision to put a man on the moon is regarded as the classical successful mega project, not only because he did what was considered an almost impossible task but achieving it generated magnificent technology spinoffs, moving America way ahead of the world in technology. However, there was a more serious reason for the project that went beyond mere scientific curiosity. The US needed to regain the upper hand in the Space Race where the USSR had made some spectacular early gains, gains causing anxiety in the American people as well as defence concerns for the government. Americans were used to thinking of themselves as the pre-eminent ‘can do’ people of the world and these early moves by the USSR were impacting morale. So, in that sense, JFK’s announcement could be considered a successful move whether or not Apollo actually landed on the moon. (At election times, how many mega project announcements could be seen simply for their announcement value?)

I started to think of other successful mega projects, like the building of the Panama Canal. Again there were multiple layers of reasons for the project – defence, trade, global power, engineering daring do – and, of course, the use of new and untried technology to solve both anticipated and unanticipated problems.

It led me to ask the question – what are the characteristics of succesful mega projects?

2. Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Maybe it was thoughts of engineering success, or maybe the resurgence of interest in rail projects recently (the Very Fast Train, the Inland Freight Rail Track, the Melbourne Metro Loop), but my thoughts turned to the legendary Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who, amongst other things, masterminded the rise of rail in the UK. I wasn’t many pages into Steven Brindle’s “Brunel: The Man Who Built the World (Phoenix Press, 2006) before I started to see parallels with the time in which Brunel lived and where we are now.

When Brunel was born, (1806) England had just won a great naval victory against France – using wooden ships powered by wind! Most people at that time travelled by horse power and buildings were made of brick or stone. By the time he died in 1859

“ iron-hulled and steam-powered ships had arrived, pioneering new materials and methods of construction had been utilised in the fabrication of buildings that – in their scale and design – were like nothing man had ever constructed before and the road and the canal were being challenged by the new railway system with horse power gradually being replaced by steam power.” Brindle, Steven. “Brunel: The Man Who Built the World (Phoenix Press).

The Age of Disruption

The changes that occurred during the 50 odd years that Brunel lived, relatively speaking – power, transport, organisation and governance – were, at the very least, as disruptive as those that we face today. The era of steam, iron and rail was just beginning and Brunel ran with it.

What, I wonder, would Brunel be doing today?

I doubt that he would be building rail (the equivalent of the status quo wind powered wooden ships in Brunel’s time). Maybe he would be designing track for automated driverless cars and carriages, and building in solar energy access. Or maybe implementing the Hyper-Loop? In any case, would he not be advancing the state of technology?

Which brings me to ask the following questions:

-

Do mega projects need a technology advancement component to be successful, especially today, when technology is driving everything?

-

What other mega trends, if any (climate change, demographics) trump this or can/should they also feature?

-

Does a mega project require a ‘mega’ purpose – e.g. defence, global domination, economic or environmental survival?

Our Situation

The world is running out of raw materials and fresh water and is being overburdened with waste and the global construction industry is a major contributor being the largest consumer of resources and raw materials of any sector, responsible for about 33 per cent of emissions, 40 per cent of material consumption and 40 per cent of waste.

Our Challenge

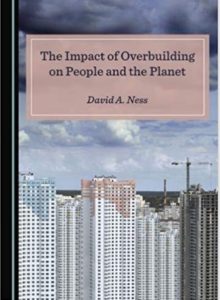

In seeking to deal with this by advocating carbon neutral cities and a “sustainable” built environment, David Ness says that all the talk is about increasing efficiency of operational energy (heating, cooling, lighting) and reducing associated greenhouse gas emissions.There is a failure to account for resource consumption and “embodied carbon” in our buildings and we need to take this problem seriously. We need to find better ways to “reduce, reuse and recycle” in the construction industry. For anyone in doubt about the seriousness of this situation, look up the Guardian’s Concrete Week, five consecutive articles about the dangers of concrete as a construction material and major landfill component.

Our Question

How can we curtail this excessive resource consumption and waste production and protect our quality of life?

Our Guide to Action

And make no mistake, the size of this problem and the extent of the misery that we will experience if we do not solve it, means that we must all take action – as consumers and producers, as users of buildings and infrastructure and as those who write the policies that allow continued abuse or generate potential improvements.

In ‘The Impact of Overbuilding on People and the Planet’ (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019) David A. Ness provides a guide to action, following the recommendations of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg, 2002, ‘which affirmed that all countries should promote sustainable consumption and production patterns by establishing a “sound material-cycle society”, in which the consumption of natural resources is reduced and environmental impacts are minimised. In both developed and developing countries, the key to achieving this was seen to be the promotion of the 3Rs (i.e. reduction, reuse and recycling of waste) in addition to ensuring the sound disposal of waste.’

David’s ideas are backed by years of research in Australia, Asia and especially China – and they are new, innovative, but also practical! “If we can make use of and adapt existing building and infrastructure stock, we save new carbon and resources,”

Practical Application

“We also need to design any new structures for ease of disassembly, adaptation and reuse, as part of a ‘circular’ built environment.” And to put this into practice he has been working with Arup. .

In 2017, the UniSA research team, of which David is a lead player, was awarded the Arup Global Research Challenge to further pursue his ideas. Part of the New Royal Adelaide Hospital was selected as a test case, with radio frequency identification tags attached to potentially reusable building components such as partitions, ceilings, doors and facade panels, and information such as location, size, type, and age of those components uploaded to a database. This successful ‘proof of concept’ opens the way to the next step – some commercially viable applications. It shows there’s an opportunity here to re-use systems that were previously sent to landfill or at best recycled for their raw materials,

The project has allowed the team to take advantage of relatively new technologies like BIM (Building Information Management) systems and cloud-based database storage systems to help track, categorise and organise building elements in a way that was never before possible.

What can you do?

There are many ideas in this book that you can combine with the latest technology if you are research inclined. But for me, the major impact of the book is on global mindsets. What we have for long taken as natural, normal, and indeed beneficial – that is, ever more building and construction – ‘more cranes in the skyline’ – are not natural, and we need to consider carefully whether the benefits they provide are worth the damage that they inevitably cause. This is not to say we should not build more, just that we need to do more to establish whether any particular proposal is of NET benefit.

For all who have a social and environmental conscience and concern, read

The Impact of Overbuilding on People and the Planet’ by David A Ness.

Hobson’s choice

Saturday before last as I stood in line to vote, the woman next to me said she did not believe that either of the major parties had policies that were helping Australia. I said that view was widely shared. Between us we decided to vote for the Party that fielded a local female representative and also a federal female representative on the basis that if we had enough women we could moderate the most egregious of profit seeking decisions and instead focus on proposals that helped people. The election results were hardly cheerful in that regard.

Yet the sun still shines, the leaves turn russet and gold, and we continue to do our best. I cannot complain. Any week in which you reconnect with an old friend and also solve a month’s long problem has to be a pretty good week.

David Ness – and the impact of overbuilding

I am a member of Research Gate, an academic organiation that keeps track of citations of your articles so you know who is using your work and what they are doing. Even though I ceased to be an academic years ago, every week I get one or two citations and this past week I discovered that David Ness, one of my first PhD students, and now an Adjunct Professor at the University of South Australia, was launching his first book ‘The Impact of Overbuilding on People and Planet” published by Cambridge Research Scholars. We had lost contact with each other years ago as both of us busied ourselves in our own work and David travelled extensively in Asia whilst my own travel was mostly Europe and North America. I rang to congratulate him and we met for coffee and talked for hours. A happy time. I will tell you about his work in my Wednesday post.

A problem solved.

A couple of months ago while I was in Melbourne to promote the ideas we were developing in Talking Infrastructure, Sally Nugent (the former CEO of the Asset Management Council) had suggested that if we wanted people to think more seriously about infrastructure decision making we would do well if we could develop a framework that others could use, and also find a way so that the fruits of their application of the framework coud be made widely available so that all can share in the learning. I had to agree it was a great idea, but at the time I could not think of how we could do it. So it sat on the back of the head as ideas do.

Meanwhile I had met Kate Quigley (at a bus stop!) a visiting American who was teaching Civil Aviation Management at the local campus of the University of South Australia. We discovered we shared an interest in teaching the art of creating good questions and she asked me if I would speak with her students. I agreed, and in designing an approach that I thought would be both educational and entertaining I thought of the hypothetical I had created for EAROPH in Brisbane and designed a question version that would lend itself to classroom teaching. As I thought about this it seemed to me that it also fitted Sally’s requirements. With Laura Mabikafola,General Manager, Skills Lab, (a Sage Group company), we are now in a testing phase, but it definitely seems to have promise for application not only in a lecture theatre but also within organisations or associations. Early days yet, but I will post more after we have done our testing.

Reading

David Ness: ‘The Impact of Overbuilding on People and Planet”

The Senate Inquiry – and Political Reactions

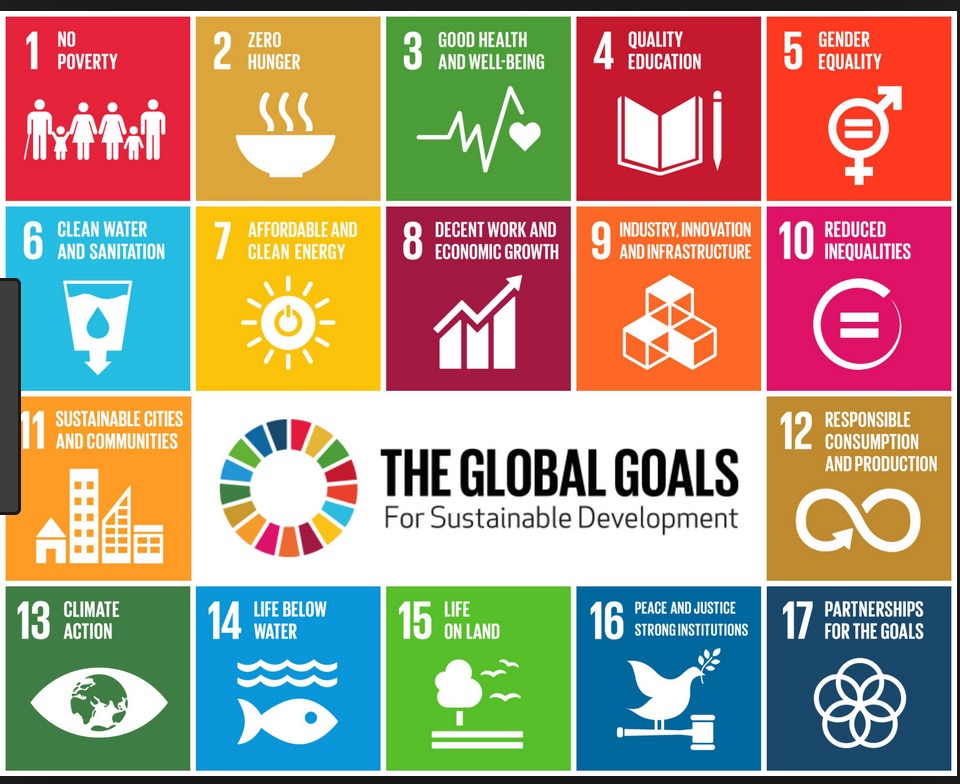

A few weeks ago in Brisbane I ran my first hypothetical. Its focus was the implementation of the United Nation’s 17 sustainability development goals. These goals, known as the SDGs, are for basic things like clean air and water, reducing hunger and poverty, increasing the quality of education, reducing gender inequalities and, in general, making life better for all Australians.

The results of the Senate Inquiry into the SDGs had just been released with a majority report (by Labor and the Greens) that said that the SDGs were important, we should be doing more, and recommended actions we could take. There was also a dissenting report (by the Liberal/National Coalition) that said, in effect, we were already doing everything and nothing would be served except more paperwork and anyway we don’t like the UN because it criticizes us unfairly (I’m not kidding about this last bit, this is what they said!) – and it concluded by saying ignore all the recommendations in the main report. So, there was not a lot of bi-partisan agreement there!

Well. who has the right of it?

Are we doing everything already or do we need to do more? According to a recent report by the Griffith Centre for Sustainable Enterprise, that looked at how the SDGs were being addressed (or not) in the policies of ten political parties.

“Australia’s ranking of 37 on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) dashboard indicates that for a developed country there are aspects of Australian society that need to be altered if it deserves to be placed in the top 20 OECD countries”.

Australia has signed up to achieve the UN goals by 2030, however if the minority report correctly reflects the view and intentions of the Liberal/National coalition, we will not be able to rely on Government. Australian progress will need to be driven by concerned individuals and groups – our growing CIVIL SOCIETY, of which Talking infrastructure, along with many professional associations and NGOs, is a part.

Where to start?

The first thing to understand is that most people are unaware of this thrust by the United Nations. Ask anyone! Few know what they are. Many think that they don’t apply to us, but are for developing countries only. This is likely because of the UN’s earlier millenial goals which did apply only to developing countries.

The second thing is that there are 17 of these goals, with 169 specific targets. This is far too much for most of us to get our head around. Fortunately we don’t have to. Pick one or two that you feel strongly about and work to improve those! (just be aware of the others and mindful that what you do might impact another goal.)

Talking Infrastructure is now working with participants in the Hypothetical – all of whom were sent as representatives of their associations – to discuss what next steps can be taken since all of 17 goals either impact, or are impacted by, the infrastructure decisions we make.

Add your ideas to the hypothetical

The set up is this

” Six months have passed and the new government urgently wishes to address the issue of implementing the SDGs. Moreover it has realised that it has major leverage that has so far been little discussed – its power of the purse!

The Federal Government funds national infrastructure projects and provides substantial support to State and Local Government projects. The best and brightest (YOU) have been gathered together to explore how to take advantage of this.

Write some rules for evaluating infrastructure proposals so that they support the SDGs and Australia’s wellbeing.

Footnote: Thanks to EAROPH Australia for their courage in letting me play with this idea for them at their AGM

It has been a momentous week in Australia with our Federal Elections and the death of Bob Hawke (perhaps the last Prime Minister who was almost universally liked and respected – even by those who voted the other way) But throughout it all, each of us has got on with their life and work. This was my week. It started with a problem.

The Podcast

We had recorded our first podcast with many contributors. Gregory Punshon, our IT Director, had done a sterling job on the production side in between repairing major storm damage to his property and a run of internet outages, so that, with the exception of a small section we wished to re-record, our first episode was almost ‘in the can’. Happiness all round! Then we discovered we had been gazumped! AECOM had launched a podcast of their own called ‘Talking Infrastructure”. It was a sister podcast to ‘Talking Cities” that they had launched last year. It wasn’t focused on infrastructure decision making but it did have our name.

It took much of the week, but what initially appeared to be a serious problem, eventually resolved itself. We changed the name and in the process, developed a unique, stronger, clearer focus. Happiness returned. It just means a delay whilst we re-adjust – and, yes, re-record! More to come.

The Hypothetical

A few weeks ago, I ran a hypothetical for EAROPH Australia’s AGM, following the release of the Senate Inquiry Report into the implementation of the United Nation’s 17 Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs). Given that the Liberal minority report to the Senate inquiry hardly reflected enthusiasm, despite the fact that Australia has signed up to implement these goals by 2030, it looks as if the task of making Australia both fairer and stronger will fall to the Civil Society ( professional associations, community groups and NGOs) of which Talking Infrastructure is a part. I have written up the work done in Brisbane so that others can join in the fun of the hypothetical. I will post this on Wednesday.

Hope for the Future

The happiest conversation of this past week was two hours spent with a 19 year old barista at our local coffee shop. Chelsea is articulate, bright, cheerful, confident and, when not working, is studying criminal psychology. She is well informed about issues of the day and passionate about taking action to combat climate change. I have high hopes for this generation – provided that we do not damn their future by selfish infrastructure decisions made today. Let us not too blithely assume that just because we can ‘create jobs’ today, it is worth our young people having to pay the cost later. .

Researching :

Green infrastructure

Reading

Oren Klaff: Pitch Anything

Recommendation:

Worth exploring if you are a woman, employ a woman or want to support women in infrastructure Leadership. Criterion Conferences’ “Women in Transport and Infrastructure Leadership Summit” 19th – 22nd August 2019, Rydges on Swanston, Melbourne.

Yesterday I was asked what question I could put before political candidates in the federal election. I sent this.

The next Global Financial Crisis

Last Friday the US 1-10 year yield curve inverted, meaning that people are now willing to accept a lower return on ten year bonds than on immediate 1 year lending, the reverse of what we would naturally expect and what is normal. This is an indication of gross market angst. Over the last 50 years, such an inversion has always been followed by a US recession within the next 24 months or so.

Such a recession could trigger global debt defaults and since debt levels are much higher now than they were at the time of the last financial crisis we can expect that the impacts will be more severe – significantly on employment, on inflation and on house prices. Whatever triggers it, we can expect that there will be another global financial crisis.

Mistakes we made last time

In the last financial crisis we attempted to control the worst effects by investing in infrastructure and construction packages, but fast tracking infrastructure led to gross wastage through hasty and poor decisions being made, and the Government later scrambled to claw back the money it had spent by reducing operations and maintenance funding – leading to further losses. We did come out of the last GFC reasonably well, but at a significant cost.

So my question for political candidates, particularly any who aspire to the position of Treasurer, is:

” What do you plan to do to stabilise the Australian dollar in the event of the next financial crisis?”

Infrastructure is more than a collection of projects

When we are faced with a GFC, the sooner we intervene, the smaller the intervention needs to be. So anything with a sizeable gestation period – like infrastructure – is a poor answer. It is often suggested that we hold a stock of ‘shovel ready’ projects (to use the American term). This is easy, but we don’t do it. And I would argue, nor should we!

Thinking in terms of ‘projects’ rather than ‘infrastructure systems’ is wasteful and unproductive. Wise infrastructure decision making is not about roads, it is about our transport systems; it is not about a hospital, but about our health systems. Infrastructure decision making requires careful planning and time to ensure that the correct integrations are made.

All of which suggests that infrastructure is NOT a good answer to short-term, stop gap, financial crises – of the local or the global variety.

So what is? Almost anything else! Anything that gets more government money into circulation and received directly by those most disadvantaged, who need to spend it straight away. Teacher’s Aides or similar would be good, for little training or equipment would be needed to get them into work, and recovery money would not be siphoned off into exports.

Thoughts?

Integrative Asset Management in Holland

Rob Schoenmaker, currently with Delft University, has been appointed to the position of Professor of Asset Management at HZ University of Applied Science. This is a brand new program, not part of engineering, business studies but entirely independent. The aim, in line with the integrative principle of asset management, is to span the boundaries between various disciplines. So he is involved in (civil) engineering, industrial engineering and management, data science, economics and international business management. The lot!

His role is to focus on research, to create long-term relationships with public and private organization, to get real life situations that can be studied and used in the various curricula. All with the end in mind: toeducate the professionals of the future using real problems and challenges.

User Stories

One of the first reaps of the harvest of spanning the boundaries between disciplines is the technique of ‘user stories’. Data scientists use this technique within their CRISP-DM[1]method to determine data mining requirements or goals. This technique has proven to be very useful to get to the core of what asset management professionals need to know.

User stories in ‘software speak’ can seem quite remote. Here it is in simple English. The official format of a user story is:

As <my role> I want <action/characteristic> in order to <reason>.

For example:

As a maintenance engineer I want to know the number of defects of component x in week y to understand the performance of the system.

It starts with a priming question –

What do you want to know/to do but never got the opportunity to find out/to do?

Professionals in this position can readily come up with dozens of questions covering what they really want to know – and why they want to know it. Rob then takes his harvest of questions, creates some order out of the chaos of stories and sorts them into certain categories, which in turn become input for the next discussion.

Behind finding the answers to the user stories lies the paradigm of ‘data-based, evidence-based’ and Rob says the real fun is to combine asset management with data science techniques.

“ What we intend to do, is to get long term relationships with public and private asset owners/managers in our region. We will do research on their areas of interest – this requires a budget, mind you – and we have lecturers-researchers work on the project, together with students. The lecturers-researcher can integrate the projects they are working on in the modules/courses.

Another way of working together with the asset owners/managers, is to define projects and apply for (NL/EU) subsidies. Once awarded this also results in a multi-year collaboration.

As an example: Together with my colleague of Data Science, we are now in the process of writing a proposal for risk-based, data-based AM in municipal sewage system management. This area is facing a lot of rehabilitation work in the coming decades, plus challenges caused by heavier rainfall, longer periods of dry weather, tighter budgets, pressure for transparency, etc.

Smaller municipalities often don’t have the budget for R&D, lack capacity (and often capabilities) to apply complicated AM techniques. And don’t know how to use the data they are sitting on. What we intend to do is to create a ‘fit-for-purpose’ (sorry: couldn’t find a better phrase) AM toolbox and incentivise inter-municipality collaboration. Again, asset management is doing this in close cooperation with data science – and we started off several months ago with collecting user stories.”

Universities in Australia have also been developing graduate courses in practical research methods and case studies as described by Rob Schoenmaker, but using ‘user stories’ for this purpose and feeding information back into curricular development is innovative.

This is question asking at its finest – providing both learning and teaching.

Talking Infrastructure has used a modified form of Rob’s ‘question and response’ format to establish what it is that our own multi disciplinary listeners want to know about infrastructure decision making. Responses are now being collated and you will be able to see the results in our first podcast episode “What do you want to know?”

[1]CRISP-DM:Cross Industry Standard Process for Data Mining (Chapman et al., 2000)

Without a way of understanding the nature of a ‘better question’ this is mere tautology. If we get a better answer then it must have been a better question! However, since we will not know until after the event, this is not a useful way of determining the nature of a ‘better question’.

I asked Talking Infrastructure Vice Chair, and Technology One Super Star, Jeff Roorda, for his view. This was his response.

-

Better questions are those that explore the future possible impacts of today’s decisions.

-

Better questions are those that recognise that the future is uncertain and do not seek to provide false comfort by claiming certainty in the assumptions we make and the outcomes we predict.

-

Better questions look at the things that could happen, and their costs and consequences, so that we can develop scenarios that act as a guide to the way we need to react as the world changes and as we get more information and more feedback.

-

Better questions recognise that we can choose the futures we want, and provide us the means to achieve them.

-

Better questions enable us to put in place a future accountability for present decisions.

These questions have 2 types of power and here Jeff focuses on the constructive power.

If we view the universe as a place of abundance and love then these 5 questions engender hope, gratitude and joy. These are the thoughts of creativity, invention and collaboration. The opposites are scarcity, greed and fear and both joy/gratitude and fear/scarcity are perceptions that are real in ones mind. They are a choice. Leadership is a choice for creativity, invention and collaboration, therefore joy/gratitude. Control and desire for power is the opposite and also a choice.These 5 questions shine a light of truth on perception so we can see what is in error.

If someone says “this infrastructure project will provide these benefits” then this must be tested now and in the future. In a spirit of joy/gratitude we recognise that our understanding is imperfect so we are not afraid to admit the uncertainty of our project/solution. We invite better ideas. Criticism and attack have no meaning – if someone has a better idea we welcome it and test it in the same way our idea was tested.

How does this square with your idea of ‘a better question’? We not only invite better ideas – we warmly welcome them. Your thoughts help us to do a better job. Please comment.

An idea worth exploring.

Two suggestions:

- Read Tina’s article in Fast Company, “How Reframing a Problem Unlocks Innovation,”

- And watch for our forthcoming podcast where we will have fun – and you will too – exploring questions.

Recent Comments