Mama

It was 2016 and I was engaged to train Auditors-General in the Pacific area in how to approach infrastructure performance audits. Their audit offices, like their countries, were not well resourced and they could ill afford to waste time and resources. It was important that they focused on the key issues and got their messages across to decision makers. With my colleague, Kerry McGovern, I spent a week in Port Moresby. At the closing party I was honoured with the title ‘Mama’. I thought this was simply a recognition of my age, but no, “mama” meant a wise woman who leads a village. I was enchanted! Who would not want to be wise and lead a village? And is this not what councils do?

So when approached last week to help the UN who are preparing a manual to assist local governments in under-developed countries struggling to adopt AM, I was happy to oblige. I spoke with Kerry and we prepared out ‘top dozen’, as follows.

What needs to be added?

- Build with your own labour and your own local materials. This will ensure you have the skills and ability to maintain what you build.

- Learn to say ‘No’ when donors offer to build something for you with their labour, or to use imported materials when local alternatives are available. Always seek out alternative practices that use local. Welcome financial assistance if, and only if, it strengthens the ability of your own people in the construction, operation and maintenance of the new assets. That is necessary to ensure that the assets will remain functional.

- Prioritise. Do not accept ‘nice to have’ assets, such as sports stadia or entertainment centres, even as donations, if you have more critical requirements in power, water, roads or communications.

- There is no such thing as a ‘free asset’. Every asset costs you. Not only does it require continuous operational costs such as lighting/heating/cleaning, but it will distract the attention of high level decision makers away from other issues.

- ‘Best practice’ and ‘high tech’ can be deceptive. The real ‘best practice’ is the one that you have the skills and abilities to apply over the longer haul. The same for ‘high tech’. The more complicated the technology the more chances are that something will go wrong and that you will be unable to fix it without outside help. And that help may not be available when needed.

- Give your Auditors-General responsibility for auditing the performance of all public infrastructure for both effectiveness and efficiency – and fund and train them in the ability to do so.

- Be clear on what is to be achieved. Assist the Auditors-General by ensuring that all infrastructure proposals – whether with local or donated funds – state clearly the expected outcomes, in addition to cost and time.

- Identify who is going to operate the asset, who is going to maintain the asset – both scheduled maintenance, and unscheduled maintenance and the costs of enabling the operation and maintenance over the entire life of the asset. Then, with that estimate to hand (and preferably arrived at with input from the people who are going to do it) identify the source of funds to pay for all this.

- If using loan funds to pay for the asset, add interest and redemption payments to the operating and maintenance costs. Ensure you factor in the administrative costs of meeting lender requirements, including the cost of training staff to meet them.

- You may need to train workers to operate and manage the asset. Negotiate with the education department to find out what is involved in ensuring a supply of skilled people, able to operate and maintain the asset and administer loans / grants for the asset.

- Consider how the country is going to set up the support systems to enable the asset to function as intended. For example, if a road, what vehicles will be using the road? where will people obtain these vehicles? how will they be maintained and operated? Who will pay for that? What income streams will cover the costs of the asset PLUS using the asset in your country.

- Plan for the safe treatment of waste generated by the asset (in both construction and use – eg. disposal of old cars, mitigation of petrol fumes, unused bitumen, water run off, etc.)

Your suggestions? (add in the comments box below)

Irina Iriser, wikicommons, pexels.com/photo/tilt-shift-lens-photo-of-blue-flowers-673857/

Is it our job to defend resources and projects for the things we fancy doing?

Two encounters in the past month got me thinking about business cases. Names have been changed to protect the guilty.

One was being asked by a team to prove they need more resources; the other was from a team desperate to defend the resources they have, post Covid-19. Both are perfectly understandable impulses. But not, I think, necessarily good Asset Management.

In the first example, a small group had been putting in place some good, basic AM foundations – sound techie things, like proactive maintenance. They want to go further, but they are having trouble persuading top management to support them. “All the exec cares about is finance, so we have to make the case by showing how much operating cost they can save immediately through Asset Management.”

They wanted us to give them hard evidence of maintenance savings, based on fully quantified examples from not only their own sector, but from organisations exactly like theirs. And full details of how those other organisations had achieved them.

I’m not complaining here about the argument about maintenance – I have moaned enough about that often enough. What struck me was this group’s belief that only immediate opex savings would convince their top management, because ‘everyone knows’ top management only thinks about money. But the AM team itself was not interested in any case based on the medium and longer term.

When we asked them if they had any reason to believe their organisation was currently wasting money on the wrong maintenance, or had more maintenance people than they needed, the team was very offended. They did not, themselves, care about costs; they just wanted to do some more cool AM-y things.

They wanted to be handed a business case for what they already wanted to do.

Without looking at the data in their own organisation; without being made to think about the real business priorities, which didn’t much interest them.

The other example was a capital projects department putting forward their reasons why the team – developed to design and construct major growth assets – should stay the same as their organisation cuts back on any growth in response to a calamitous lose of income from Covid-19. I was amused, if that is quite the right word, by how they used the language and principles of whole-life Asset Management to justify no cuts to engineering. When what they really care about – is building shiny new things.

As I said, I can understand both motivations. But – I believe – it’s focusing on what you want to do, fun techie things, and then coming up with a justification for it afterwards in whatever ‘business’ language you can find to hand, even if you personally don’t believe it, that plagues our infrastructure decision-making.

And exactly what good Asset Management should not be doing, right?

Photo from commons.wikimedia.org, Escaping the jaws of a Banzai Pipeline wave

In the third part of our audio series on the Waves of Asset Management, we move on to talking about time.

Because effective Asset Management practitioners are time travellers, working with past, present and future: understanding where we are now, using historical experiences and data, in order to model the future.

What can Asset Management bring to better future planning? What must we bring? And what tools do we need to do this?

Part 3 of a discussion between Penny Burns, Ruth Wallsgrove, and Lou Cripps, in our new Thinking Infrastructure Aloud series. Please let us know what you think!

The wonderful ‘Big Picture’ animation from the Institute of Asset Management ends on a fascinating note:

Once we have optimised all our asset decisions to deliver our organisational goals – we can move on to asking about “the very reasons for the organisation’s existence”.

In part 2 of our audio series on the Waves of Asset Management, we explore alignment, a core principle of the Second Wave, or, Strategic Asset Management.

Hard as alignment is to achieve in practice – all those 1000s of asset decisions that have to add up in a co-ordinated, integrated way, now and into the future – it can raise an even bigger challenge for Asset Management practitioners. What are we aligning to?

What is the real purpose of my organisation?

And how can Asset Management help define it?

Part 2 of a discussion between Penny Burns, Ruth Wallsgrove, and Lou Cripps, in our new Thinking Infrastructure Aloud series – enjoy!

And let us know what you think!

Photograph by Andréa Farias Farias, Herdi no pedaço., CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=83076806

In 2018 Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda suggested we describe our history in revolutions; a month ago, Penny proposed the history of Asset Management is more like Waves.

The First Wave of AM was to establish an asset inventory. We needed to know what we had to manage before we felt we could do anything else.

The Second Wave was to do something useful with this information: Strategic Asset Management, or better decisions to get a better answer in terms of cost, risk and performance. Of course, once we started actually using the data, we became much more aware of data quality and coverage. The need for good information didn’t go away. The best Asset Management practitioners are mostly still in Wave 2 – but already looking beyond it, for example in response to Covid-19.

The coming Third Wave is what Talking Infrastructure is all about. How to use what we have learned – all that data, sure, but more what’s involved in making better asset decisions – and look ‘up and out’ to the questions of what infrastructure our communities really need now, and into the uncertain future?

In March this year, after lockdown began, three of us – Penny Burns, Ruth Wallsgrove, and Lou Cripps of Denver Area transit agency RTD, across three continents – took the framework of the Three Waves and explored what this means to us in practice. Talking Infrastructure is happy here to deliver Part 1 of the recording, the first in an on-going series called Thinking Infrastructure Aloud that we intend not merely as audio downloads but public podcasts.

You get to be the pilot for this, and so: it is even more vital that you comment, and give us feedback on our move into sound!

1. How do our experiences match your own?

2. How to ride these Waves into the future?

3. And do you like this audio?

NOTE: Part 2 of The Waves Podcasts is also now available at www.TalkingInfrastructure.com

Homo Sapiens is a pattern seeking species

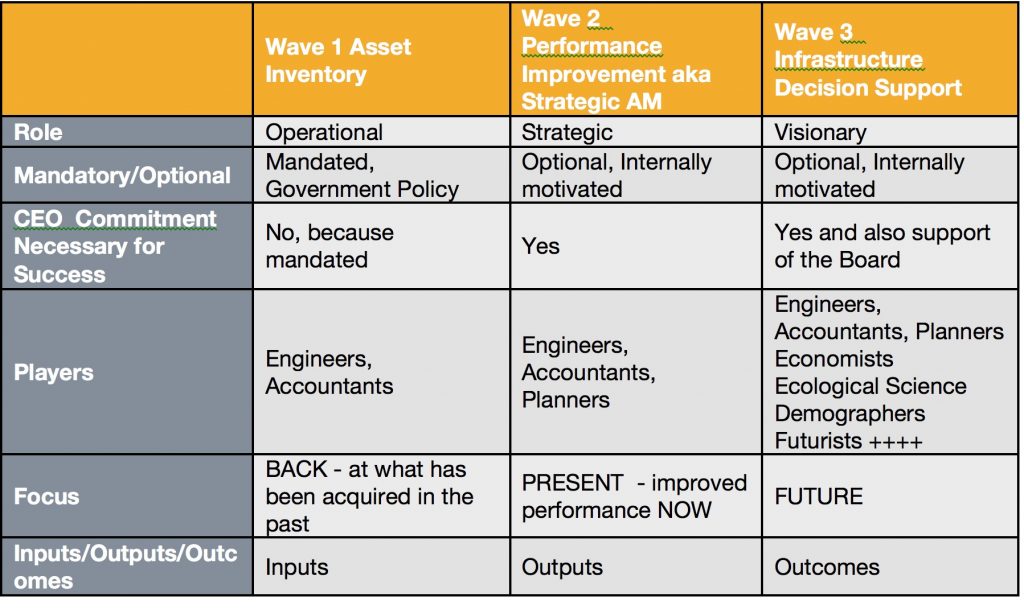

it is how we advance. We seek patterns to find meaning. Me, I look for patterns in AM development. I seek the characteristics of the different stages (that I now think of as waves rather than as revolutions, as explained in the last post) and how each builds on the one before and takes us further. This helps me to see not only where we have been but also where we can go. Each wave has its own focus, viewpoint, key players and sources of support as well as constraints. Below is a table illustrating some of the characteristics of the first three waves that I see. What do you think?

Where we have been and where we are

Waves 1 and 2 you will readily recognise, for they reflect where we have been and where we are. Wave 3 is where we need to go next. This is the visioning stage where asset management teams, use their appreciation of ‘line of sight’ or the necessity for asset actions to support organisational objectives to guide decisions on both new and existing infrastructure. This is where AM teams need to anticipate, communicate, and prepare for the inevitable shifts in attitudes, governance and demand, that are now occurring and will continue to occur as demographics, climate and technology change. Turning around large infrastructure portfolios is not an overnight task. It takes intelligent planning and communication. This is Wave 3.

Where we are going

Communication, anticipation, action. In Wave 3 AM teams help their corporate managements to explicitly recognise that the asset portfolios and management practices they have now are a reflection of the past, and that the future will be very different from the past and will involve new thinking. This may seem obvious, but it is not necessarily happening at the moment. Sometimes it seems that it is easier to assume that nothing will change very quickly so we can continue doing what we have always done. And sometimes the lure of the new and shiny leads to adoption of the new without sufficient examination.

The Wave 3 challenge is not to jump straight into the new and exciting, but rather to determine how best to reduce the twin dangers of changing too early, and of moving too late.

The biggest change will require us to ask what changing circumstances and future communities will DEMAND of us, what the new needs will be, and not to look at new technology as merely an opportunity to change the way we SUPPLY the current needs of our customers and community.

From Supply to Demand. In the past most of the information we have needed for our decision making in asset management has been internally generated and recorded in our Asset Information Systems. This has been solely supply side information. We still need our supply side information. But this will not suffice. Knowing what we CAN do is not enough. We need also to look at what we MUST do. For this, we will increasingly require the ability to understand and anticipate future demand change. This is why our our asset management teams will need to expand to include the talents of many other professionals, as I have suggested in the table above.

Is your Asset Management Team prepared?

Is your Asset Management team prepared to tackle the third wave? If you are not sure, then a good place to start would be with “Building an Asset Management Team” by Ruth Wallsgrove and Lou Cripps. This will help you recognise not only requirements but also the many new possibilities. Here is a short excerpt “What kind of people does an AM team require?”

Note: When you buy “Building an Asset Management Team” you not only get the very latest thinking in AM teamwork, but you pave the way for future developments, for Ruth and Lou are donating all their proceeds (ALL, not just profits) to Talking Infrastructure.

So go ahead, click this link to get your copy. You can get a Kindle version for less than $10. In this case value greatly exceeds cost. It’s priced low to maximise the number of teams that can gain access. Spread the word!

I was wrong. Movement from maintenance to asset management, to strategic asset management is NOT a revolution. Why not?

In 2018, for the IPWEA’s online journal, Jeff Roorda and I sketched out what we saw as the general pattern of these individual journeys and what this suggested about where we would go next. At the time there was a lot of discussion about the third (and for some) the fourth industrial revolution. We needed a sexy title for our paper so we called it ‘The third AM Revolution’.

We saw AM moving from the pre-AM stage of maintenance only to the first stage of data collection, or ‘asset inventory’, to the second stage of performance and alignment, or what we call ’Strategic asset management’ – the stage we believe most of Australia is now in – to a new third stage, our ‘third revolution’ that we are calling ‘infrastructure decision support’.

We now see that ‘revolution’ was the wrong word.

Revolutions have connotations of what was previously important getting the chop – quite literally in the French Revolution! Although each of the three stages we identified are still important because they represent different mindsets and approaches, different groups of players and different techniques, they do not discard what went before. Instead they increase our understanding of their value and make them stronger.

Let’s see how that works.

0. Before AM there was maintenance. Maintenance specialists firmly believed in the value of their work, and they were right. Unfortunately they were unable to convince others, especially finance. When AM came along it provided a framework to demonstrate that not only was maintenance able to fix what was currently broken – it could also help prevent more breaking down in the future. That is why so many maintenance engineers were keen to see AM adopted by their organisations.

1. The first stage of AM, naturally, was to establish an asset inventory. We needed to know what we had to manage.

2. With enough basic data we were enabled to take the next step use the data collected for performance improvement. When we did this, we became much more aware of data quality and coverage. That first stage of data collection did not get the chop, now we wanted more. Instead of data being required simply for a mandated balance sheet (e.g. a storage location) it was increasingly seen as necessary, indeed essential for progress, and so demand for more data, and for data of a higher quality with greater coverage has continued.

3. The coming third stage is what will bring all of these stages – maintenance, data collection and performance improvement or strategic asset management – together, for it is at this third stage that asset managers finally reach the stage that they have desired for a long time. Asset management is able to get (and worth a) place at the board table!

So not a revolution. But what?

We could simply call them ‘three stages’ and be done with it. This, however, would not show the connection between them, how each builds on what went previously, so we are calling them waves, for like waves they build on each other and get stronger.

Why is this important?

Because now that it is so easy to access detailed information about the second wave of strategic asset management or performance improvement (IIMM, PAS55, ISO 55,000) there is a temptation is to dive in at this level. But without attention to the first wave of data collection and without strengthening the pre-AM stage of maintenance, such attempts lead to failure. Under-developed countries wanting, and needing, to do fast catch up with the developed world are at particular risk.

They are being pressured ‘to do asset management’ in order to get the strategic asset management, second wave, benefits but the importance of funding and training at the earlier stages, particularly maintenance is not being recognised and dealt with. Every stage – maintenance/pre-AM, data collection/asset inventory, and strategic asset management/performance improvement or alignment – requires a different focus, different tools, different groups of players.

I will talk about Wave 3 – where we go next – in a later post.

Q: Does this development pattern make sense to you?

Can you recognise it in your own organisation or others? Is it obvious, or do you see an alternative pattern to your own asset management journey?

Coming Next: The Three Waves

Why understanding them can help you move closer to your ultimate goal.

Ten years ago, on LinkedIn’s Asset Management History Forum, I asked “Why bother with history?” It was the most animated discussion on the forum. Now, with ten more years of history behind us, have we learnt more or do you agree with Jan Korek’s view that history is irrelevant?

This was Jan Korek’s opening statement:

“I have never subscribed to the suggestion that you need to know where you’ve been, to know where you’re going! History, to me, is little more than a badly-drawn representation of the past, based on an exaggerated impression of successes….. and an amnesia of the failures.

Having been deeply fascinated by Asset Management for a score or more years, and am still working at the blunt edge of the process, I have had to change, adapt, forget much and learn more along the way. So what do practitioners, or the process, gain from a knowledge of when (or why) some obscure government department became notionally interested in the stewardship of infrastructure assets? I would suggest very little.

Anyone who has been in Asset Management for a period of time will have grown their own unique history based on any number of influences. So what is to be achieved in distilling each individual story into an homogenised, badly-drawn fiction? Experience shows that we even fail to avoid the mistakes of the past, even when we know the history involved. The news, each day, is full of such examples.

What seems more important is the future, “Where are we now”, and “Where to from here”? Or to put it another way, you need to know where you are now, to know where your going.”

A compelling set of arguments.

Opening for the other side was John Hardwick.

Wow!

What a start to the year you go away for a couple of days and a great discussion begins. I can only say that everything i have implemented has come from others.

I have implemented knowing what worked and what didn’t. I have used this to significantly change the way my organisation does Asset Management. I am only new in comparison to many of you but it is your collective knowledge i have used.

Also I have used your history and stories that have helped many other companies not make the same mistakes. I am a strong believer that we learn from our mistakes and not to make them again.

If this is the case it is critical for new organisations implementing Asset Management to have access to some of the good the bad and the failures.

I have given more then 20 organisations access to my staff and myself over the last twelve months to learn from what we have done and the mistakes we made. The best part is I learnt so much in return it has been amazing.

History allows us to tell stories that help others conceptualise their path to hopefully a more successful future.

Also a compelling set of arguments.

What’s your view?

How has your understanding of AM history enabled you to be a better asset manager?

We are about supporting AM Leaders!

Here’s the situation we face:

We are moving into a “perfect storm” where our natural and built assets move into states of uncertainty and instability. We must rapidly build an understanding of the integration between our ecology and built infrastructure because rapid changes will increasingly challenge or capacity to foresee and manage risks. We are already seeing the initial evidence or these risks in major fire and flood events and likely pandemic events.

Growth boom infrastructure is approaching end of life, ageing population requires infrastructure realignment, climate, environment and virus risk changes start to move from debated possibility to clear and present dangers. Technology is the wild card with the potential to provide new solutions or exacerbate existing problems. Where we allocate our resources is more important than ever before.

The decisions made by this generation will determine the quality of life of future generations. A future that could be bleak and fearful or exciting, prosperous and filled with hope. Our current decision-making framework and decision support processes, systems and assumptions need rapid overhaul to support our current leaders guide us to the future we want and the following generations deserve. We can avoid reacting to preventable or manageable disasters by developing integrated rather than fragmented strategic plans.

What do we want for our future?

Talking Infrastructure’s Vision is a world in which decision makers understand and care about the cumulative consequences of their decisions and their constituencies understand the trade-offs involved in those decisions.

What do we have to stop doing?

We need to stop thinking of ‘infrastructure’ as a panacea for all economic ills, but rather to consider individual infrastructure projects and their individual contributions to general wellbeing – economic, social, and environmental. What questions do we need to ask of all projects to make sure that we are ‘future friendly’? What do we need to know about the relationship between future change and infrastructure? What changes do we need to make to current decision processes to achieve this goal? Could these resources be better allocated to prepare for future foreseeable risks.

We want to avoid infrastructure waste. Stranded assets are assets that are now obsolete or non-performing and recorded in corporate books as a loss of profit. Current estimates vary but run into the many trillions of dollars. Climate, technological and demographic changes all contribute to this problem. But so do we – when we construct infrastructure better suited for the 20th than the 21st century. Every year we use up valuable resources and add to environmental damage and often social damage, constructing long-living assets destined to end on the stranded assets scrap pile. Resources that could be used to mitigate more urgent foreseeable risks.

We believe we can do better

In the past, governments have tended to see infrastructure as an expenditure ‘blob’ – useful for soaking up unused corporate savings to ‘kickstart’ the economy or as a generic ‘source of jobs’. These are the attitudes that have got us where we are now. We believe that if we focus on ‘future friendly’ projects, that takes future change into account and specifically designs for it, we can avoid unnecessary waste and manage future risks.

This requires us not to think of ‘infrastructure’ as a panacea for all economic ills, but rather to consider individual projects and their individual contributions to general wellbeing – economic, social, and environmental. What questions do we need to ask of all projects to make sure that we are ‘future friendly’? What do we need to know about the relationship between future change and infrastructure? What changes do we need to make to current decision processes to achieve this goal?

This is what Talking Infrastructure is about!

Do you also believe we can do better?

JOIN TALKING INFRASTRUCTURE

to keep up with latest thinking and doing and join us in our work towards wiser infrastructure decision making,

go to top of the right hand column.

It’s free and you will be part of a growing number of professionals from all disciplines: planners, strategic asset managers, financial specialists, environmental scientists, economists, sociologists, administrators and many others who share the realisation that to really benefit from the many changes that now surround us, all decisions need to undertand the past, act in the present ,and be open to the futures now emerging, so

Get Involved! Members receive our monthly newsletter containing brief synopses of what we have posted during the month and opportunities for you to share your knowledge and ideas with others.

The Scene

It was twenty years ago and I was in the office of a regional council CEO. I led with an open question “How important do you think that AM is?” He was a nice fellow, he didn’t want to hurt my feelings but clearly he was not enthusiastic about the subject. “I guess it is valuable, but we aren’t going to do it!” “OK” I said, curious, “Why not?” “Well, look it’s this way, if that section of Carter’s road gets washed out in the next flood, that is where I am going to have to put my money, not into some future renewal fund!” “Entirely right”, I replied. “That will be your first priority. Can asset management do anything to help avoid that flooding problem? Can it, at a minimum, reduce your overall asset maintenance expenses to free up the funds you need?” It was clear that he had not seen asset management in this light, that is as a solution. He had equated AM with a renewal forecast, a problem. And too many still do that – CEOs and Asset Managers both!

The Story

There was the Asset Manager who presented his renewal forecast to the board and told them that they would have to double their asset expenditures. The board sacked him. And they were right to do so! That fellow was not doing his job. He was simply stating the problem and expecting others to take action so that he would not have to.

The Point

A future renewal forecast is not the end point of an Asset Manager’s task – it is the beginning. It states the problem, as accurately as can be done. But it is still only the problem. Now a solution has to be found. The task of the asset manager is to find that solution. Not to be like a certain US President who expects to be praised for doing nothing to solve the problem whilst making it worse. Indeed by not immediately taking action to find a solution that Asset Manager was making the renewal problem worse.

The Future?

Asset managers often ask how they can sell asset management to the board or senior executives. The answer is obvious (although not necessarily easy): it is to tell them how AM can solve their problems. The first step is to find out what their (not your) problems are. What do their customers, their clients, their regulators want of them? Most often when I ask asset managers what are their organisation’s key issues, they answer in terms of their own issues instead. At asset management conferences I hear people claim they want to make their organisation an outstanding asset management organisation. That is OK but it is not why your organisation is in business!

Lou Cripps, co-author with Ruth Wallsgrove of ‘Building an Asset Management Team’ ( highly recommended and available from the Talking Infrastructure website) summed it up this way.

Recent Comments