Douglas Bartlett, Manager Asset Planning, City of Kalamunda, and a member of the Perth City Chapter is our blog poster for the next four posts. Here he looks at how we might define sustainability. Do you agree? Doug welcomes your responses

In considering what ‘sustainable asset management’ means we first need to recognise that ‘sustainable’ is poorly understood. It implies a quasi-positive future benefit but is usually not defined. How else can we express ourselves if not using the word sustainable?

In considering what ‘sustainable asset management’ means we first need to recognise that ‘sustainable’ is poorly understood. It implies a quasi-positive future benefit but is usually not defined. How else can we express ourselves if not using the word sustainable?

Thomas Rau of Turntoo (http://turntoo.com/en/) is a designer, architect and thinker who is exploring a wider view of the selection and use of materials for buildings (or for any purpose). The idea is that every piece of material should be used, as long as possible, and then used again, not recycled. This includes practices such as:

- Having the United Nations adopt a Declaration of Materials Rights that prevents throwing anything out,

- Reusing existing old buildings by giving them new functions and extensions,

- Deliberately taking the building materials and parts (bricks, windows) and reusing them, but also ensuring their original design is to be reused without generating waste, and

- Asking for light, not lights. This means it becomes the supplier’s responsibility to supply the specified level of lighting for say 15 years. The supplier wears the costs of any failures so is pushed to manufacture lights that last the longest and require the least maintenance.

We could define a sustainable asset as being an asset that lasts forever and provides its service forever, with no net expenditure of energy (resources). But nothing lasts forever, so a sustainability statement is needed that defines sustainability in terms of time and resources, while continuing to provide the specified service (Lighting is sustainable if provided at the specified level, for 15 years, at agreed cost, where cost represents the energy consumption and any waste at end of life). Perhaps our asset management plans should include a definition of sustainability in terms of the assets in this manner.

Some years ago, for SAM, Ype Wijnia and Joost Warners, both then with the Essent Electricity Network in Holland, argued asset management was a strange business. Consider, they said:

Some years ago, for SAM, Ype Wijnia and Joost Warners, both then with the Essent Electricity Network in Holland, argued asset management was a strange business. Consider, they said:

A typical Asset manager works with an asset base that is very old. For example, at Essent Netwerk the oldest assets in operation are about 100 years old, and the average age of the assets is about 30 years. Each year about 3% of the asset base is either built or replaced. Typical maintenance cycles have a period of about 10 years. So, about 13% of the asset base is touched on a yearly basis.

This means our basic job is more like staying clear of the assets and letting them perform their function than it is like actively doing something with them, as the term Asset Management suggests. Therefore it might be wiser to call ourselves asset non-managers.

The strangeness of Asset Management increases further if you look at the portfolio of asset and network policies. From long experience with managing assets, most policies have reached a high level of sophistication and they address not only the general situation but all kinds of possible exceptions which have been encountered over the period since the policy was put in place. Those exceptions have exceptions of their own, requiring further detailing of the policy.

In the life cycle of a policy, attention therefore drifts from the original problem to managing exceptions. This means that as the sophistication of the policy grows, the knowledge about why the policy was developed in the first place diminishes.

Exaggerating a little bit you could say that Asset Managers do not manage most of the assets, and in case they do, they haven’t got a clue why they are doing what they are doing. You would expect a system that is managed this way to collapse very soon, but somehow it does not, as the electricity grid in Europe has a reliability of about 99.99%.

However, this way of managing assets can only work in a stable environment with stable or at least predictable requirements for the assets. Unfortunately, the world we live in is nothing like stable.

Thoughts?

In our current data driven environment, there is still a role for common sense

In our current data driven environment, there is still a role for common sense

A few years ago, using its renewal model, a council was advised that its buildings were 60% overdue for replacement. This came as a great surprise to the Council – but should it have? If true, one would have imagined that there would be many visible signs of major deterioration – non-habitable buildings boarded up for safety, signs of breakdown in buildings still in use (e.g. lifts, plumbing or HVAC not working), union demonstrations, protest movements, etc. If true, this should not have been any surprise to council, their own user experience would have told them that it was true. So what is happening here?

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.” Statistician George Box.

Jeff Roorda, in his post asked ‘why focus on the measurement of physical life using condition instead of looking at function and capacity?’ A very sound question. Function and capacity determine economic life, or useful life (how long we can expect the asset to be of use to us) rather than how long it will physically last. His question is part of a wider range of questions about how we use models.

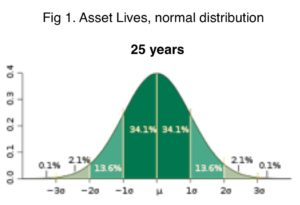

The first thing to note is that renewal models are financial models. They are based on averages of a group and say nothing about the time to intervene (i.e. replace) for any individual asset. When we say that an asset, or an asset component, has a useful life of 25 years, what is really to be understood is that assets of this type may fail at 15 years or even earlier and perhaps as late as 40 years or more but that when we take them as a whole, their useful lives will average out to about 25 years. This is a guide to financial planning.

Because 25 is an average (and assuming we have a normal distribution and not one that is severely skewed) then we can expect that half of these assets will fail before the age of 25 and half will fail after the age of 25, as shown here in figure 1. Thus we cannot assume that just because an asset is greater than 25 years that it is ‘due for replacement’

This is the mistake made by the council, and why it came as such a surprise to the Councillors.

Our instincts may not be infallible but when intuition clashes with the results of a model, it pays to check both our understanding – and our interpretation of the model.

While we eagerly await Jeff’s next episode, let’s consider the following example of City West Water that realised that ‘strategic’ and ‘operational’ didn’t have to be in opposition. This happened many years ago, but the message is just as relevant today.

While we eagerly await Jeff’s next episode, let’s consider the following example of City West Water that realised that ‘strategic’ and ‘operational’ didn’t have to be in opposition. This happened many years ago, but the message is just as relevant today.

When Melbourne Water was broken up into a headworks company and three distribution companies, City West found itself the owner of the central and oldest part of the network. One of the earliest problems it had to deal with was the repair/ replace decision. Clearly it could not afford to replace every ageing asset that was giving it problems.

On-the-ground decisions had to be made taking into account not only the condition of the asset but future rehabilitation programs and a range of other strategic considerations. This meant that maintenance crews found themselves assessing the condition of the asset, determining the problem, but unable to operate until the information had been fed up the line and assessed by the strategic asset managers. This was costly, delayed action and frustrated the maintenance crews.

The Strategic Asset Manager decided that in the ‘need to know’ context, the maintenance crews needed to be aware of the strategic decisions that affected their actions. So he ran a series of sessions in which he explained not only the strategic decisions that top management had come to – but why they had made these decisions.

Discussion was apparently quite lively. He answered all the men’s questions and then went with the men out on site. He asked the crews to assess the situation and then recommend the action required, in the light of top management strategic thinking. Within a short period he found that they were making the decisions that he would have made

– and then he let them run with it.

Comment?

We all know early option analysis makes sense so why don’t we do it?

We all know early option analysis makes sense so why don’t we do it?

Maybe there is a desire to ‘get runs on the board’, to be able to show the media, as well as government sponsors and promoters, that ‘something is happening’ and that the team assigned to the task are not dragging their feet. While a project is in the early options appraisal phase it requires a lot of flexibility – and time – from senior executives, who are the only ones who can determine when sufficient evidence is presented to enable a choice to be made as to the direction to be taken. Once the direction is chosen the work can be passed to lower levels or consultants to construct the ‘business case’. Experience with the Victorian Investment Logic Mapping work confirms the difficulty of getting senior executives to spend the necessary time on this high level decision making.

Danger of default to ‘the infrastructure solution’

In 2000, according to the UK Institute’s Report “What’s Wrong with Infrastruture Decision Making”, there was an analysis of the environmental impact of intermittent discharges of storm sewage into the Thames. They concluded that “The main problem with the early options analysis was that a mixed solution (using a combination of smaller measures to address storm sewage) was not considered in detail . This is an example of the seeming preference within government for large projects.”

The tunnel, now under construction, has a total cost of £4.2bn and will add an estimated £15-25 a year to London water bills until 2023/30. Critics say that the cost is unnecessarily high and that cheaper alternatives were never explored properly. The Institute argues that decision makers on the project may have fallen prey to perceived political risks, staff fears of expressing disagreement and decision-making processes sceptical of innovation, which made decision makers reluctant to turn back after making an early commitment.

So our inquiry today is:

-

Why don’t we do, what commonsense says we should?

-

What experiences have you had that illustrate a too quick default to the infrastructure option.

-

And what can we do about it?

Roads are a major asset, probably the major asset, of every council, so ‘doing different’ here can make a real impact. So, following on from our earlier post (Feb 6) by Rebecca Brown, here is another angle on road recyling, this time by Con Rimpass, Pavement Analysis, who looks at not just partial use but 100% recycling of roads with cold asphalt, improving on the ‘cradle to grave’ notion, by extending it to perpetual life! Both authors are presenting their work at the 2018 IPWEA State Conference, Perth, March 21st to 23rd.

Roads are a major asset, probably the major asset, of every council, so ‘doing different’ here can make a real impact. So, following on from our earlier post (Feb 6) by Rebecca Brown, here is another angle on road recyling, this time by Con Rimpass, Pavement Analysis, who looks at not just partial use but 100% recycling of roads with cold asphalt, improving on the ‘cradle to grave’ notion, by extending it to perpetual life! Both authors are presenting their work at the 2018 IPWEA State Conference, Perth, March 21st to 23rd.

Con says: There is nothing new about cold mixed recycled asphalts, they have been around, particularl in France, since the mid 1970s and known as cold mix asphalt & grave-emulsion and they have been manufactured from either new or recycled material or a combination. Cold mixed asphalt and bitumen stabilisation are used in the renewal of both pavement structures (bases) as well as for surface wearing courses and have proven economic, environmental and safety benefits.

As Perth has grown in population so too has its length of roads and these aging roads now have to withstand heavier traffic with large loads on high tech tyres pumped to very high pressures, creating a huge increase in strain on the pavement structure. Perth has a network of road pavements that have had two or more asphalt overlays without any structural improvement to support layers and there is evidence that some money is being wasted on rehabilitations that are not providing satisfactory lives.

It is not possible, or economical, to continue to just resurface road pavements for ever without stiffening the support and it is important to try and recycle as much of the existing pavement materials as possible. The government is aware of this and are encouraging the use of recycled materials.

Asphaltech, in partnership with Pavement Analysis and collaboration and support from French experts have developed a process which makes it possible to 100% recycle and strengthen pavements with minimal disruption to traffic and exposure of workers to the safety aspects of working on live roads.

For those unable to hear Con at the conference, please enter your questions in the comments section (click the ‘add a comment’ tag in the menu above) and he will be happy to respond.

Our theme this month is ‘doing different’. But it pays to ask ‘Why’? – and what may be the consequences of not paying attention to this question.

Our theme this month is ‘doing different’. But it pays to ask ‘Why’? – and what may be the consequences of not paying attention to this question.

The human mind is hardwired for novelty. We seek out what is different and exciting. And it has served us well. It has been the source of our greatest inventions. But it can also lead us astray. When I left the University to work in the public service back in the early 1980s, every heavy engineering organisation (rail, ports, power, water, telecommunications) was headed up by an engineer – a guy (and they were all guys) who knew how to get things done. At this time, ‘stewardship’ was the word most accorded to those who ‘took care of’ assets, asset management was still in the future. But as the administration gradually moved from stewardship into management, we saw a different face at the top. And these different faces were finance and accounting. These guys (again!) knew what things cost. Under this leadership, we focussed on efficiency rather than effectiveness, or, in practice, ‘getting costs down’. This was when we introduced outsourcing, later to be followed by corporatisation and privatisation. The next move at the top was to ‘content free management’, these were people who were not engineers who knew how to get things done, and not finance who knew how much things cost, they were people trained in nothing more than ‘management’ itself. And now we started to see more female faces at the top. We also started to see something else. Whereas previous heads had worked to ‘keep the show on the road’, this new crop of managers were keen to ‘do something different’. The more radical the difference, the greater the publicity that they could expect. The publicity they garnered was sufficient to move them on to the next top job. Few stayed around longer than a few years to cope with the damage they caused.

We continue to exhalt difference for its own sake. ‘Disruptive’ is the joyful current buzzword. As if disruption itself was the benefit. How many times do you find new ideas presented at conferences – and how few are the times when those same presenters return a few years later to tell you honestly what the outcomes were? In fact, In our haste to move on to the next new and shiny thing, how much time and effort do we put in to make the last change succeed?

I still believe that we need to ‘do different’ – but not for its own sake!

My question today is: If not for its own sake – what IS the purpose of ‘doing different’?

This opens up a whole realm of possibilities for using environmental science and illustrates the importance of thinking of traditional infrastructure solutions as a ‘last resort’ rather than a first! This post is by Chris Adam, Director of Strategic AM Pty Ltd, Brisbane, Queensland

Nitrogen (TN) creates problems in the ecosystem due to the tendency to create algal blooms that can disrupt the food chain. Thirty years ago point source loads (e.g. Sewerage Treatment Plants) were a problem. Who can forget the Sydney beaches of the 1980s when the wind turned onshore? Over the last 20 years we have made huge inroads into resolving these issues. More could be done but we are getting close to the top of the economically rational return to scale. So what ELSE can we do?

Nitrogen (TN) creates problems in the ecosystem due to the tendency to create algal blooms that can disrupt the food chain. Thirty years ago point source loads (e.g. Sewerage Treatment Plants) were a problem. Who can forget the Sydney beaches of the 1980s when the wind turned onshore? Over the last 20 years we have made huge inroads into resolving these issues. More could be done but we are getting close to the top of the economically rational return to scale. So what ELSE can we do?

Queensland Urban Utilities

Queensland Urban Utilities have piloted a couple of nutrient offset projects in which riverbank stabilisation and remediation (leading to a reduction in sediment runoff and therefore TN into the bay). These projects have performed really well (in fact, in the recent torrential rainfall from the tropical low that was once Cyclone Debbie, the sites not only stood up to the challenge but captured sediment!!).

Making a very long story short, the cost of these schemes seem to be in the order of $25,000 per tonne of TN. The current cost of treatment for all EXISTING Wastewater Treatment Plants is in the order of $13,000/Tonne (no surprises here – the return to scale of the existing network is the most cost effective option for removing nutrients). However the cost of augmentation of treatment plants starts at $50,000/tonne. So, what does this mean? We sweat the existing treatment plants (even overloading them hydraulically if necessary) as that’s the cheapest nutrient removal option. However, the next best option seems to be nutrient offsets through land remediation.

There are challenges here in that the regulator will currently only allow offsets against wet weather flow (this is based on the logic that the offset program only removes sediment during rain events which is an assumption that we could debate). The “least best” option is augmentation of the plants (i.e. “hard engineering” that locks in a centralised service model and ignores potential technical obsolescence of the plant itself).

The US EPA have gone further and have set up nutrient trading markets as a mechanism to manage/minimise TN discharge across point and non-point sources of pollution. A similar scheme has been in operation in Lake Taupo in NZ and there are schemes (in the early stages of development) being piloted for the Great Barrier Reef).

What this means is that the water services engineer of tomorrow will definitely have to think beyond the traditional “engineered” solution and understand the issues across a much broader range of inputs/outcomes. It’s very interesting times .

Thoughts?

Our post today – with thanks – builds on an idea by Rebecca Brown, Manager Waste & Recycling at WALGA, who will be presenting at the March WA State Conference of the IPWEA. (details below).

The first stage to ‘doing different’ is to imagine!

Rebecca says: “Imagine a road that is made from completely sustainable products and when it wears out will be used as the input into another road or project. All the materials will circle through the system again and again. This is the aim of the circular economy and the direction our State is going. Instead of the current linear economy model – dig, use, dispose, in the Circular Economy approach no materials go to waste, everything is an input into another process.

That may seem like an unattainable goal, given WA currently generates about 2 tonnes of waste per household/year, but for civil works this aim is completely achievable. Using old roads for new, using innovative materials and sourcing high quality construction and demolition materials all provide us with a way to move towards achieving a circular economy in WA.”

At the forthcoming WA State Conference of the IPWEA, “Rebecca Brown, Manager Waste & Recycling at WALGA will provide a brief overview of the Circular Economy approach and how it fits into the State Government’s new direction, provided by an updated State Waste Strategy. Drawing on lessons from over 10 years of experience using a range of recycled materials, Colin Leek, an industry expert, will share his experience and present case studies of how to use these materials to close the loop. Dave Markham, Chair of the Waste Management Association C&D Working Group will explain the processes in place to ensure that high quality process.”

The second stage to ‘doing different’ is to extend.

In other words to see if we can apply what we have learned in one situation – for example, as in the above, for renewing existing roads – to totally new situations.

Can we imagine a situation where, instead of accruing more and more roads, we are able to decommission an existing road in favour of a more relevant route – return the road to arable, residential, or park lands – and re-utilise the road materials in the new location?

What would it take to make this idea reality?

A new month – and a new theme. This month we are looking at ways of ‘doing different’. To introduce this theme, what better than to use the Ted Talk presented in 2009 by adman Rory Sutherland (kindly drawn to my attention by Hein Aucamp, one of our regular contributors).

A new month – and a new theme. This month we are looking at ways of ‘doing different’. To introduce this theme, what better than to use the Ted Talk presented in 2009 by adman Rory Sutherland (kindly drawn to my attention by Hein Aucamp, one of our regular contributors).

In this talk Rory argues that the role of advertising is to create intangible value (or perceived, subjective, or ‘badge’ value). His opening story tells of a group of engineers who, some ten years previously, were asked how to improve the train trip from London to Paris. The engineers come up with a solution requiring the construction of new rail tracks to the coast, costing 6 billion, to cut 40 minutes off the then 3.5 hour travel time. Rory considered this a particularly unimaginative solution and presented his alternative – employ the world’s top male and female supermodels to walk up and down the train handing out free Château Pétrus. “You’ll still have about 3 billion in change, and people will ask for the trains to be slowed down!” In other words, we can improve the trip by making it more enjoyable rather than simply making it shorter. His whole TED talk, which you can find here, is a great example of this – so enjoyable, you wish it were longer! It is also full of ideas that may be used to help change focus and produce better results – by ‘doing different’.

So this month we are looking for examples of ‘doing different’

– examples that will improve outcomes (social, environmental and economic) by reducing the draw on scarce resources, a ‘less is more’ approach to infrastructure and construction. Your inspiring examples welcome. Please send them to me at penny@TalkingInfrastructure.com

And don’t forget that you can join in discussion on earlier blog posts.

The posts are designed as conversation starters. Show your appreciation by adding your perspective, your suggestions, your experience.

Recent Comments