I’ve long been fascinated by the idea that we need ‘bridges’: people who can translate between two domains with different mindsets.

One key gap to bridge is between science and management, as Penny describes https://talkinginfrastructure.com/2022/07/20/science-and-asset-management/ . There are other gaps that affect us in asset decision-making.

In the late 1990s two of us, now very senior IT director Christine Ashton and me, put forward the need for such active translation between IT and business users. IT has always struggled to understand what’s really needed by users, as the users themselves are poor at describing their information and information processing requirements.

Christine and I set up a special interest group in the British Computer Society – an organisation which could do with some translation in the first place – for people who work between IT and business. We had a great time discovering some very good people, who, I am happy to say, generally earned pretty good remuneration for their ability to understand what the users need and turn it into something IT techies could understand (and use). It’s still a rare and precious ability.

And it’s surely still as big a challenge as ever.

Add to that how to bridge between an engineering mindset and business. I train engineers who still radiate – why do I care what the objectives of the organisation are? My job is to do the right thing by the asset, regardless of management.

It’s fascinating in all three cases, because scientists, just like engineers and IT in their different ways, are kinda proud of their ability not to compromise with business and organisational realities.

In particular, the issue of ’embracing’ uncertainty is just so relevant to Asset Management. But we educate scientists, engineers and IT to hanker after 10 decimal places of clarity.

And, I fear, not to ask ‘so what? – or, what happens next?’ as often as they should.

Popularity can be the death of a good idea.

Make a term, or an idea, popular and any number of people will latch onto it and attach it to their own agenda – and it doesn’t matter if their agenda is diametrically opposed to yours. In fact, it might serve them better if it is.

For example, I have seen instances of the term ‘asset management’ taken over by developers, applied to office cleaning, and, of course, to maintenance itself. The one I really objected to was the developers. Figuring that their own term had come into disrepute this particular group had decided to take ours!

We see what we want to see

Another problem with communication of ideas is that we tend to see what we want to see.

Years ago the Public Accounts Committee produced a report showing how much would need to be spent on hospital infrastructure renewal IF nothing was done by way of better maintenance, accounting and planning practices (ie without better asset management). A few days later the Minister for Health, completely ignoring the intent of the ‘if’ statement (as people are sadly inclined to do) profusely thanked the PAC Chairman since this ‘proved’ he needed a larger budget!

On another occasion, I was walking in the city when the State Treasurer dashed across a busy main road to tell me enthusiastically that it was thanks to me that the State had kept its triple A credit rating! What?! I had looked at our asset base and saw a future renewal problem that threatened to dwarf the state’s budget, however the credit agencies had looked at the dollar value of our assets – which we had made visible for the first time – and, ignoring the budgetary impact of restoring the deterioration that had already occurred and would need to be attended to, saw only billions of dollars in assets. We are all subject to this restricted vision. We see what we want to see.

All of this is by way of saying that the term I used almost 30 years ago for accounting for infrastructure has long since been hijacked, and by so many, that it is unwise to continue using it. So, I want to start again with greater neutrality.

The Goal

First: let us be clear about the task – namely to develop financial metrics that drive good infrastructure management and meet the need for financial responsibility and accountability. This requires genuine dialogue between two disciplines – and a listening ear.

Let’s start with a thought experiment

There may be lots of things you like about the current way in which we account for infrastructure, but what don’t you like? Are there problems that it creates for you or your organisation?

What’s your story?

How can you plan for the unknown – when you literally cannot see your own hand in front of your face? Well, back 12 years ago, when she headed up the Strategic Asset Management Team at RailCorp (now Sydney Trains) I facilitated a scenario planning exercise for Ruth Wallsgrove. The scenario we looked at was an epidemic with an immediate impact on ridership, with everyone – although, of course, we didn’t call it that – ‘social distancing’. Now over to Ruth to look at the implications that has for us today. PB.

The importance of planning

“Emergencies are overrated as a response mechanism. Are preparation, prevention, and planning about to become more popular alternatives? Can we nudge this? “

Planning – that is, thinking ahead and co-ordinating what we are going to do – appears to be central to dealing with Covid-19. We do not know for certain what the conclusions will be, except that South Korea seems to be doing well, and the USA not.

The nature of planning

I teach AM to a lot of people, and quite a lot of them ask how you can plan when you don’t know exactly what’s going to happen. The answer is, of course, that it is even more important to plan when you don’t know exactly what will happen. The point is to give yourself a framework for flexibility. No planning ahead at all gives you nothing to work with.

It would not have been a sensible plan to stockpile ventilators. And there was no possibility to stockpile Covid-19 test kits, because they didn’t exist. Good planning instead would be putting in place the thinking processes that would enable us quickly to ramp up production of known equipment, and to come up with new tests and vaccines.

Scenario Planning

Scenario planning seems to me to be the opposite of Planning with a capital P: the opposite of a high up committee coming up with a visionary Plan for transforming our infrastructure.

The idea of scenario planning is to look at alternative scenarios, and ask what the data tells us. It’s to consider what to do if the future doesn’t go the direction you want it to. What you can influence. How you can stay nimble to respond to what reality tells you.

The Chain of Consequences

In our scenario planning session in 2008 we were asked to consider – Could an epidemic lead to an increasein ridership?

Trains and buses are currently empty not just because people don’t want to be in a small space with many other people, but because many of us are in lockdown. Our workplaces have closed and, if we are lucky, we are working from home. (If we are not… we are out of our paying job, temporarily or permanently).

What if: people go on being nervous about crowded spaces after we go back to whatever the new normal is?

Well, one possibility is that everyone heads to their cars with a vengeance. But what if that led to impossible traffic jams, as most cities already had no spare capacity for personal vehicles?

What if: someone comes up with a neat way to avoid breathing germs on each other? This was one of our scenarios. How could the chain of consequences lead to an increase in ridership? It’s not even hard to do, once you free yourself from thinking you ‘know’ what people will do, or should do, in future.

Along with scenario planning, we also need the skills to go beyond the immediate, and ask what the knock-on impact of one event on another. Such as the basics of AM: if I build this rail line, what will that mean for operating expenditure for the next thirty years? What does it mean I can’t do, because I’ve dedicated resources to this rail line instead of that arts centre? What are possible impacts on our overall capabilities – including the environment? (There is always another Plan, but no Planet B…)

The role of Asset Management practitioners

In late 2018, when a wire down led to a wildfire that burned down a town in California, much attention was paid to control the spread and mitigate the fallout. The AM team were involved, however, not in initiatives to look at the urgent immediate risk, but rather in the important task of what to put in place to reduce such risks in the future. So often, as we know, the urgent drives out the important.

We are not emergency planners; that’s an honourable discipline in its own right. Our job is to consider scenarios and chains of consequences (“and then what?”) and building flexibility into our asset systems and our processes.

And our Question Today:

What steps can we, as Asset Managers, start taking to prepare for the next pandemic?

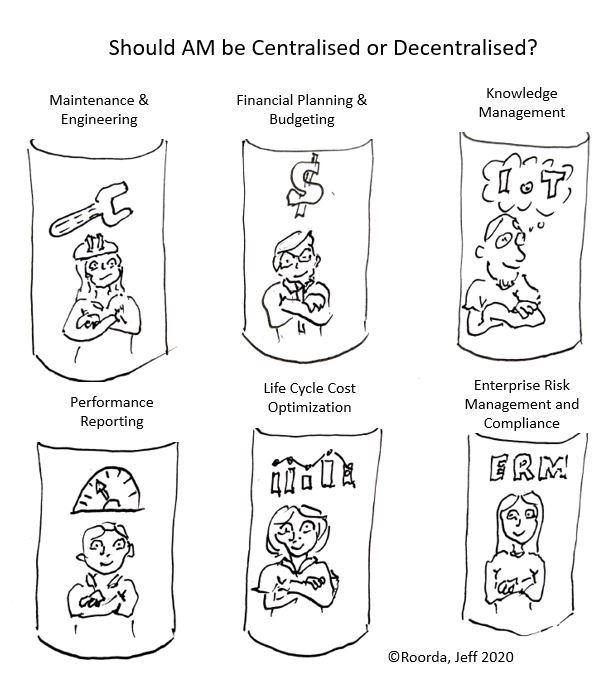

Whether asset management should be centralised or decentralised has been asked since the beginning of Asset Management (AM) as a structured activity. Many organisations have cycled through these structures, some several times. We have seen both models succeed and struggle. Before considering which organizational structure is best, we can learn from what has worked in the past.

The common primary success factors are a good asset management team leader with top management (ISO, 2014) support and commitment over the long term. Without both of these in place, fragmentation into silo’s of finance, maintenance, construction, compliance and knowledge management is the most common result. Often these silos are in adversarial competition for resources with short term horizon of less than 5 years.

The key focus of the ISO 55000 series and IIMM is the role of the AM Leader and the interaction with “top management”. Leadership is not the same as management although they are complementary and often overlap. (IIMM, 2015). A secondary, but essential success factor is at least 2 people who are proficient and have experience in asset management. (Wallsgrove, 2020)

With these success factors in place, that is, top management commitment, a good AM leader, and at least 2 people with AM knowledge and understanding, a centralised structure has a lower likelihood of fragmentation into the AM silos mentioned above.

Good communication skills are the essential attributes of a leader to communicate throughout the organization how the organizational objectives are to be converted into asset management objectives (ISO 55000 2014, 3.3.2). This manages the primary risk of fragmentation of asset management into competing silos with fragmented or inadequate skills.

Both international source documents, ISO 55000 series and IIMM are consistent in defining the roles and responsibilities of asset management in an asset intensive organization as much more than maintenance management.

References

IIMM, I. I. (2015). IIMM International Infrastructure Management Manual.Sydney: IPWEA.

ISO. (2014). ISO55000.Geneva: ISO.

Wallsgrove, R. and Cripps, L. (2020). Building an Asset Management Team .Amazon .

AMQ International’s ‘Strategic Asset Management’, ed: Dr PennyBurns, Issues 270, 298, 371

Footnotes

1. SAM 270 looks at different structures, all of which were adopted successively by an Australian Rail Company when they discovered the problems with the one they were currently using. The whole issue looks at organisational structure.

2. SAM 298 pp 3-5 ‘Four models of AM organisation within councils’

3. SAM 321 ‘A Perfect AM Organisation?’ pp 1-3

4. Roorda (JRA) was the Asset Management Consultant for BART from 2012 – 2015 and established a successful asset management programme for BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) with John McCormick and Frank Ruffa. AM Council News and Asset Management Implementation and Integration Frank Ruffa

Sometimes you ask a question and the answer is unexpected but once read, so completely obvious, you feel an idiot for not seeing it in the first place. Read this exchange on bushfires (and value) between Jeff Roorda and me – but mostly Jeff.

Jeff:

The devastating fires that have blighted Australia in 2020 have now burnt through 18.6 million hectares of land. The fires had a total perimeter of 19,235 kilometres. That’s the equivalent distance of Sydney to Perth four times over and further than Sydney Australia to Los Angeles USA.

An estimated 1 Billion animals were killed, and entire species or plants and animals may have been wiped out. 33 people died and 2,779 homes were lost.

The cost to fight large fires is very high and growing with questions about the effectiveness of reactive strategies. We have avoided putting a value on air, fire, water and earth because it doesn’t neatly fit into our built infrastructure silos.

A large fire shows not only the connections of our artificial silos, but is instructive in a better understanding of value, cost, benefit and risk. These are the inputs to asset management plans. Decisions can then be based on scenarios based on evidence, expertise and experience to come to a wisdom decision for future generations.

We understand cost and cost and value are connected. The cost to react to crisis is high and growing but cost should be based on an asset management plan that has benefit, cost, risk and value of decision scenario options.

Penny:

Fires do not confine themselves within council boundaries, or even State boundaries and this was amply demonstrated in our recent (indeed still current) fires. Asset management plans are necessary but they are, sadly, not sufficient. How do we go further?

Jeff:

If any future event is identified then there are options to mitigate that event. Examples are a large fire, reliable energy or water or infrastructure congestion or under utilisation. Not making a decision or not having an evidence based asset management plan with possible scenarios is actually a decision to run to fail.

This often happens because we think we can’t reliably measure value. But when we get to the point of run to fail we can measure cost. In 2017, the NSW Government invested $38 million over four years for three Large Air Tankers to be used in firefighting efforts. In December 2019, the Federal Government announced $11 million on top of the annual $15 million. Add to this State and Local Government Costs and the opportunity cost of over 72,000 members just in NSW.

So there is a connection between cost and the value we put on something. Concepts such as deprival value and service potential become useful. Cost is a proxy for the value of what we lost, human lives, houses, businesses, over 1 Billion animals died and some flora and fauna may be extinct. A better concept of value is essential to making long term decisions for future generations.

“Private firms efficiently finance their operations or they fail”

Clifford Winston, Brookings Institution.

There are a lot of implied assumptions here! Where do we start?

A major implication is that private firms must therefore be more efficient than public firms, but this makes a massive assumption – namely that the losses to the community from those private firms that fail is of lower consequence to the community than inefficiencies of public sector organisations that are not allowed to fail.

Where has this ever been rigorously and neutrally examined? And if it had – why would we have persisted so long, throwing good money after bad, at the UK private sector firm, Carillion? Carillion, which employed 43,000 people to provide services in defense, education, health and transport, collapsed in January, becoming the largest construction bankruptcy in British history. It left creditors and the firm’s pensioners facing steep losses and put thousands of jobs at risk

We tend to regard as heroes those entrepreneurs that go bankrupt – perhaps many times – and then come back and make a fortune. That latter fortune, however, is financed (involuntarily) by many small entrepreneurs and their families, some of whom may well have gone out of business because the work they did for our bankrupt hero was never paid for.

There have recently been a number of very large and very public failures in the banking system that have created enormous public havoc. These banks cannot ‘go bankrupt’ but can – and are – bailed out by the public, which is the equivalent. Without this ‘safety net’ and the incentive to make a profit ‘no matter what’, would a public banking system, such as we once had, have fallen prey to the sub-prime mortgage debacle?

Have the so-called ‘efficiencies’ created by a private banking system been systematically weighed against the costs? I suspect that this is an area where we are acting in ‘blind faith’. It has to be blind because there is so much to the contrary that we can see if we but look.

Another aspect of this faith is the presumption that anything that we may say in favour of private sector or ‘market‘efficiency’, still holds true when the private sector is propped up by government contracts (e.g.public toll road contracts).

I am not arguing that there are not problems in the public sector. There are. But would it not be an idea to address these problems directly rather than advocate private provision where there are also problems – but they are less amenable to correction?

When are we going to get that definitive examination of Carillion and hold them responsible?

Yesterday I was asked what question I could put before political candidates in the federal election. I sent this.

The next Global Financial Crisis

Last Friday the US 1-10 year yield curve inverted, meaning that people are now willing to accept a lower return on ten year bonds than on immediate 1 year lending, the reverse of what we would naturally expect and what is normal. This is an indication of gross market angst. Over the last 50 years, such an inversion has always been followed by a US recession within the next 24 months or so.

Such a recession could trigger global debt defaults and since debt levels are much higher now than they were at the time of the last financial crisis we can expect that the impacts will be more severe – significantly on employment, on inflation and on house prices. Whatever triggers it, we can expect that there will be another global financial crisis.

Mistakes we made last time

In the last financial crisis we attempted to control the worst effects by investing in infrastructure and construction packages, but fast tracking infrastructure led to gross wastage through hasty and poor decisions being made, and the Government later scrambled to claw back the money it had spent by reducing operations and maintenance funding – leading to further losses. We did come out of the last GFC reasonably well, but at a significant cost.

So my question for political candidates, particularly any who aspire to the position of Treasurer, is:

” What do you plan to do to stabilise the Australian dollar in the event of the next financial crisis?”

Infrastructure is more than a collection of projects

When we are faced with a GFC, the sooner we intervene, the smaller the intervention needs to be. So anything with a sizeable gestation period – like infrastructure – is a poor answer. It is often suggested that we hold a stock of ‘shovel ready’ projects (to use the American term). This is easy, but we don’t do it. And I would argue, nor should we!

Thinking in terms of ‘projects’ rather than ‘infrastructure systems’ is wasteful and unproductive. Wise infrastructure decision making is not about roads, it is about our transport systems; it is not about a hospital, but about our health systems. Infrastructure decision making requires careful planning and time to ensure that the correct integrations are made.

All of which suggests that infrastructure is NOT a good answer to short-term, stop gap, financial crises – of the local or the global variety.

So what is? Almost anything else! Anything that gets more government money into circulation and received directly by those most disadvantaged, who need to spend it straight away. Teacher’s Aides or similar would be good, for little training or equipment would be needed to get them into work, and recovery money would not be siphoned off into exports.

Thoughts?

A reoccurring theme in our questions is the discussion of the unknowns, how do we go about making the right infrastructure decisions, what are questions we need to ask and find answers to.

A reoccurring theme in our questions is the discussion of the unknowns, how do we go about making the right infrastructure decisions, what are questions we need to ask and find answers to.

We can use as an example the recent and exciting debates over the efficacy of tearing down and rebuilding various stadia in NSW. Setting aside the significant politicking associated with announcements, defending decisions, backflips and the like; the following is clear:

The policy(1) of the NSW government state:

“[W]orld class facilities and ensure Sydney remains the major events capital of Australia.”

“[C]ritical to attracting big-ticket events and visitors, maintaining a strong NSW brand and generating social and economic benefits.” The cost-benefit ratio for the projects hover around 0.6, meaning there is a net cost to the community for generating the benefits.

“[E]nables NSW to bid for and host a wider range of events.” Also at net cost to the community.

The residents of NSW did not believe these are worthy goals, certainly not at the anticipated cost. A petition for reviewing the decision gathered over 200,000 supporters including the Lord Mayor of Sydney (2).

It is certainly not clear how these projects “support liveability for the people of NSW.”, another stated benefit of the projects.

An additional interesting item is reported that “When cabinet first approved the government’s policy of building two stadiums at a cost of more than $2 billion last November, ministers were told the BCR for Allianz was 0.6; potentially up to 0.8 if the value of the asset when it was not being used was counted.” (3) From an Infrastructure Decision Making perspective this is troubling as it indicates that the asset is significantly idle, but more importantly, that ministers may be encouraged to think of cost benefit analysis as flexible, that an idle asset returns value to the community.

Sydney’s Lord Mayor is also reported as stating “she still had not seen a comprehensive business case for rebuilding or remodelling the stadiums.” (4)

From the reaction to the announcements and the public response it is clear:

- The decision-making process for replacing the stadia was not sufficiently robust to withstand the weight of cursory public scrutiny.

- The achievement of benefits that exceed the cost of the project is not a significant motivator for decision makers.

- Claimed financial benefits from policy could not be substantiated.

My question, posed by Rob Didcoe, is “What information can we provide that will allow politicians to make the best possible decisions on behalf of the community?”

1. https://sport.nsw.gov.au/aboutus/OOS/SIG/nsw-stadia-network

2. https://www.change.org/p/premier-berejiklian-stop-nsw-government-wasting-2b-rebuilding-sfs-olympic-stadiums

3. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/state-politics/gladys-berejiklian-crunching-the-numbers-for-stadiums-rebuild-funding/news-story/4c830abd5b2087047c0a3d28d956c972

4. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-03-29/nsw-government-backs-down-on-stadiums-backdown/9600654

The third in our series on ‘words matter’ by Douglas Bartlett, Manager Asset Planning, City of Kalamunda. Do you agree? As usual, Doug welcomes your responses and alternatives.

Grenfell Tower Fire June 2017

Risk management, when taken to its root cause, is about the potential harm to an individual. But not just any individual, it is the harm to the person assessing the risk. We are all, by nature, selfish and will always assess and measure things against ourselves (no matter how gracious and service oriented we may be). If I assess the risk of a Bike Plan failing to deliver its outcomes, I can talk about how the community won’t get the health benefits or maybe safety improvements that it needs, but whether these things happen or not is irrelevant to me unless I (personally) can be affected by it. I can be affected by getting blamed for the failed outcomes, or by losing reputation. So the core perception of risk comes down to how the individual perceives the threat of harm.

Risks are ‘managed’ by introducing practices that are thought to decline the level of risk. Risks (in terms of AM planning) are typically recorded only for significant events, and treatments are also typically not analysed in detail. So the activity of risk management in AM may suffer from a lack of detail, and also may suffer from the assumption that management practices will manage the risk.

In my job, I am uncertain on a day to day basis. I am uncertain when I reply to a request for a new path, because I can’t be sure if the path is really needed. I am uncertain when a developer wants to discharge stormwater into the drain pipe, because despite the calculations and standards there are a huge number of assumptions being made. From an analytical and statistical perspective, I am uncertain most of the time.

So which term is more useful? In consideration of our selfish natures, is it more harmful to me to be uncertain or to try to manage risk? I am uncertain on a day to day basis and it does not appear to be causing me harm. By implication then I won’t try to change practices where they appear to be working (no matter how uncertain they may be). So, I think Risk is the better term as it will drive a reaction from the individual.

‘Just the facts, ma’am’ – was a catchphrase made popular by Detective Joe Friday in the TV detective show, Dragnet. The implication was that it was he, the detective, who would interpret the facts, for we do not make decisions based on the facts, but rather on our interpretation of the facts.

‘Just the facts, ma’am’ – was a catchphrase made popular by Detective Joe Friday in the TV detective show, Dragnet. The implication was that it was he, the detective, who would interpret the facts, for we do not make decisions based on the facts, but rather on our interpretation of the facts.

Interpretations can vary widely. In 1987 when the PAC revealed for the first time, the full extent of the cost of replacing all of South Australia’s public infrastructure in South Australia, I interpreted this as a liability to be planned for so I was unprepared for the State Treasurer to thank me most sincerely for ensuring that the State retained its triple A rating! A triple A rating when it was facing a quadrupling of its asset renewal within the next 15 years and had no idea of what to do about it, how was that possible? Simple: the ratings authority had been persuaded (as, unfortunately, so had the government itself) to interpret the replacement cost of assets as the ‘value’ of the assets and, since this value exceeded the measured value of the debt (ignoring future replacement considerations), all was considered to be well.

At least if the facts are clear, we can debate the interpretation (see Evidence based decision making). But what if the facts are wilfully distorted?

The ABC reported last Thursday (June 14) that 40% of infrastructure spending is now ‘off-budget’. This translates to being invisible for most. Even Saul Eslake (the former ANZ chief economist and member of the Parliamentary Budget Office’s panel of expert advisors) is reported to have ‘only noticed the scale of such spending days after the budget lock-up, as he went through the finer details in hundreds of pages of Treasury papers”. The ABC says that he isn’t the only one now paying attention – and perhaps we all should!

The Government is effectively treating this infrastructure as a ‘financial investment’ which implies a financial return. A case of wilful blindness since most of its infrastructure spending not only will not provide a financial return but will require further commitment of resources to manage and maintain.

We need to see the facts as they are, not how they have been massaged to appear. This can happen in major cases such as the above, but also in smaller ways in our own organisations.

With infrastructure, what we choose to see – and choose NOT to see- may have serious impacts for many generations to come.

This is a case to follow.

See

The Budget 2018 Sliced and Diced.

The 2018 Budget contains hidden investment time bomb

Recent Comments