My last post examined Thomas Kuhn, who gave us the language of paradigm shifts, here, I’d like to look at a book by Michele Wucker* who gave us the image of the Gray Rhino: a massive, obvious threat we can see coming but still fail to confront.

Where Kuhn focused on how systems break and are replaced, Wucker draws attention to the crises we recognize but still choose to ignore.

Asset Management exists at the intersection of these two frameworks.

Asset-intensive organizations are surrounded by gray rhinos. Infrastructure gaps, aging systems, climate vulnerability, workforce attrition, regulatory pressure: these are not surprises. They are slow-moving, well-documented challenges that, if left unaddressed, will overwhelm the system we rely on.

Yet for all their visibility, these threats rarely trigger the level of change they demand. Instead, they are absorbed into routine. Budget cycles roll forward. Work orders are prioritized by urgency rather than consequence. The language of Asset Management is invoked, but its paradigm is never fully adopted. We name the problem but struggle to act on it.

Asset Management offers an approach precisely designed to engage these looming risks. It asks us to plan, to prioritize, to see beyond the emergency response. It invites organizations to realign their values, moving from reactive service delivery to deliberate, long-term stewardship.

But as Kuhn would note, this requires a change in the underlying logic, a shift in how organizations understand value, success, and time.

Until that shift happens, Asset Management remains vulnerable to reinterpretation. The system continues to operate within the old paradigm, where short-term efficiency trumps long-term value, and where the urgency of today erodes the preparation for tomorrow.

This is not a failure of awareness. It is a failure of transformation. We see the gray rhino, and we have a framework for responding to it. But our systems, both technical and cultural, are still optimized for a different reality.

So, what do we do with this tension?

We start by recognizing that paradigm shifts don’t come from force. They come from readiness.

And readiness grows in moments of discomfort, when the cracks in the current system become too wide to ignore. When organizations feel the weight of the gray rhino pressing closer, they become more open to doing things differently.

Asset Management must be positioned as more than a practice. It must become a way of seeing the world around us. Using a lens where the familiar takes on new meaning and is a guide for what to do when the warning signs are no longer abstract.

Most importantly, Asset Management needs its champions. People who can not only name the gray rhino and frame the conversation but offer a path forward that is both pragmatic and bold.

Change can be slow, but it is also inevitable. Those that prepare will be the ones best positioned when the shift finally takes hold.

The gray rhino is here. The question is whether you will continue to ignore it or finally take action to avoid being trampled.

*The Gray Rhino: How Recognize and Act on the Obvious Dangers We Ignore, Michele Wucker, 2016

Julie and I produced this after a recent discussion with Ruth. I think it’s a discussion we’ve been having for years.

Todd Shepherd & Julie DeYoung

Once upon a time, or so the story goes, Asset Management started to take sprout at our organizations with a bold promise. It came to guide us toward long-term thinking, to help us look beyond next year’s budget and into the decades ahead. It came with principles and frameworks, a philosophy that assets are not isolated items, but interconnected parts of a whole. The decisions we make today shape the quality of life for future generations. It was a different way of seeing how investing in the right place, at the right time, could save money, and public trust.

But then Asset Management met The System. And The System did what it always does: it absorbed the new idea and bent it back into something familiar.

Instead of being a strategy for long-term stewardship, Asset Management became a new label for what we were already doing. We turned it into a more refined version of the same habits: squeezing the last bit of life out of aging assets, reacting quickly to failures, and deferring investment until the next crisis hit. We framed these actions as efficiency, as cost savings, as smart business. But they were just survival tactics. And so, when Asset Management started to bloom, it was quietly, subtly, reshaped.

What was meant to be transformational became transactional.

Long-term planning? That would have to wait. We needed to fix the latest failure, explain the recent cost overrun, patch the emergency before the news cycle caught wind. The capital planning calendar was full of yesterday’s fires. Asset Management was drafted into service as a better way to react.

Rather than change The System, Asset Management was absorbed by it. It was translated into the language of short-term cost savings and immediate returns. “Get more life out of your assets” became a directive, not to optimize lifecycle value, but to defer replacement as long as humanly possible. And The System applauded. Budgets tightened. Work orders increased. Failure response times improved…until they didn’t.

This isn’t a failure of individuals. It’s what happens when a new idea runs headlong into The System. The System reward firefighting over fire prevention. It promotes leaders who solve today’s crises, not those who quietly prevent tomorrows. It allocates resources to what is visible, immediate, and politically expedient. And so, Asset Management is quietly reshaped until it fits.

A discipline focused on resilience and long-range value becomes a sophisticated way to do what we’ve always done: squeeze, stretch, defer, and repeat.

Asset Management, instead of being a disruptor, became domesticated.

The truth is, Asset Management requires a paradigm shift. It requires a new way of thinking about value, responsibility, and time. It asks us to see past short-term wins and start building for long-term resilience. It asks leaders to stop managing symptoms and start addressing root causes. It asks organizations to measure success not by how fast they respond to failure, but by how rarely failure occurs at all.

That’s a hard shift to make. It means unlearning habits, changing incentives, and having the patience to invest in what won’t pay off this quarter. It means making space for new voices, new metrics, and sometimes uncomfortable truths.

But if we want Asset Management to be more than a buzzword, we need to protect it from the status quo. We need to give it space to grow before we ask it to perform. And most of all, we need to let it change us before we change it.

To do that, leaders must become designers of systems, not just managers of outcomes. They must ask: What behaviors are we rewarding? What stories are we telling? Are we building a future, or just managing decline?

Asset Management didn’t fail. It simply wasn’t given a chance to take root. But the story isn’t over. It’s still being written. And if we’re willing to change the system, we might just change the ending.

My team makes use of premortem thinking: as part of planning action, immediate or long term, consider how it might go wrong. We think ourselves into the future looking back at a project (or a meeting). Humans are surprisingly good at this time-travelling.

For me, this is part of a principle Asset Managers should embrace: the principle of reversibility. It’s not just about understanding the consequences of our decisions, but also about planning for the ability to undo or reverse their effects if needed. Sure, you can’t un-ring a bell, but we can find ways to get as close as possible to the pre-action state and minimize the impact if we think about it right from the start.

Do our plans have exit strategies or an undo button? None that I have seen, why not?

This is especially crucial in infrastructure projects, where large investments and long lifespans magnify the potential impacts. How would they be delivered differently if that was required? Would that requirement cause us to better maintain the infrastructure we currently have? I think so.

Let’s face the hard questions: Can we put rare earth metals back in the ground? Can we undo the energy consumed in building something new?

By embracing the principle in Asset Management and infrastructure decision-making, we can strive for resilient and adaptive systems that serve the present while safeguarding the future of generations to come. We navigate challenges with eyes wide open.

We ask tough questions, anticipate consequences, and face the answers with truth – and then we create our plans and strategies.

Is this the AM curse? Every election year we are presented with some impossibly expensive infrastructure project which generates great excitement – and acceptance. Invariably these projects are unaccompanied by any detailed analysis, for it is the idea itself that is so compelling, and so analysis just spoils it.

Is this the problem with AM? Are we trying to sell the detail, when all that is wanted – indeed all that can be absorbed by the general public – is the vision? This is not to say that detail is not needed but without an exciting vision, why will people listen?

I am looking for examples of good AM ‘visions’. Do you have, or know of, one?

In the early 1990s asset managers were so absorbed in the culture conflict between engineers and accountants that we gave short shrift to another conflict, that between scientists and management. If asset managers are now to effectively deal with the climate and environmental issues around infrastructure today this is an issue that we need to address. For this, I don’t think that we can do better than start with the excellent article by marine ecologist, Peter Cullen – also dating from the early 1990s.

In this article, Peter looks at the reasons for conflict between scientists and managers and suggests that there are three major reasons why it is difficult for scientists and managers to ‘get on’

- Friction between scientists and managers is often the result of misunderstandings about the culture within which each works.

- Many of the question that both are trying to solve are value questions not scientific ones or management ones.

- Managers often misunderstand science and expect it to deliver a truth that is nonarguable. They fail to understand the very process of science demands no such truths, so that assumptions, methods and conclusions can always be challenged.

He believes that the answer to this problem is to develop a ‘broking role’ – for people who understand both the scientific and management approach to provide a translation.

His argument about managers expecting science to provide a ‘truth that is non-arguable’ is an important one – and those who are currently disputing the ‘truth’ of global warming would be well advised to read and think about this short but powerful article.

However, I want to draw attention to what he has to say about cultures.

Understanding the cultures

“It is necessary to appreciate that the cultures pervading science are quite different from the cultures that pervade management. Without appreciating these cultural differences we will continue to be frustrated at the inadequate communication in both directions. Within professional ranks there are various mind sets inculcated during training and professional socialization. They can be parodied.

- Engineers don’t care why it works as long as they think it does.

- Scientists don’t care if it works or not as long as they understand why.

- Economists don’t care either way if the internal rate of return is OK.

- Managers don’t know unless someone bothers to tell them.

- Planners know how it should have turned out.”

The culture of Scientists

This includes sharing and openness through publication, conference presentations, travel;

honesty limitations of data/evidence;

emphasis on peer review;

organized scepticism;

peer rewards from quality of insights, experiments, analysis;

peer rewards for ability to select appropriate problems that have intellectual difficulty rather than immediate usefulness;

low status of data collection unless it is to test some hypothesis;

higher status for explanatory theories over empirical models;

some independence about what problems scientists will work upon.

The culture of management

- Managers have as their goal the delivery of benefits to some group. These might be abstract or generalized (policy) or specific (service delivery).

- Managers make decisions in order to reduce risks and they make pragmatic decisions to try to achieve this.

- Decisions are normally made with imperfect information and there is little pressure to review subsequently the assumptions in the light of effectiveness.

- There is often pride in the ability of managers to make decisions with little knowledge, and a culture which does not encourage quantitative evaluation and accountability.

- Technical skills are not directly valued in organizational hierarchies, and professionals have to become managers if they seek advancement to higher levels.

The Source of Conflict

Science is valued as a weapon in the ongoing conflict with other interest groups or agencies for power, influence and resources. Scientific outcomes, and the kudos of success, may be less important than staking out the turf to keep other players at bay. Public sector management appears to be undergoing a paradigm shift at the moment, and so there are two conflicting models.

(a) The bureaucratic model. The bureaucratic model has rules that are made to be followed. Following procedure is more important than particular outcomes. These systems are characterized by due process and formal procedures, rule books, secrecy and avoidance of performance review. The system rewards rule conformity, error avoidance and attention to detail.

(b) The managerial model. The managerial model is characterized by quantifiable outcomes that are more important than following set processes. Services are seen as products to be delivered to customers. There are devolved responsibilities within an externally set cost framework, and managers are assessed through cost-effectiveness reviews. Hence economic rationality replaces the legal and procedural framework of the bureaucratic model. The organization is seen as a tool in the hands of the executive manager or Minister, and is responsive to short-term political agendas. Rewards are for achieving output targets and nonachievement may be punished. Creates an environment where there must at least be a facade of progress, so if a problem is intractable there will be attempts to abandon it so at least the impression of progress can be created by moving on to new and relevant problems” .

What action do we need to take?

As Asset Managers we often get frustrated and annoyed when our ideas of what needs to be done runs counter to what others want to be done. Unfortunately a common response is to consider the others wrong, ignorant or even malicious. But let us first understand what they need to do to achieve their desires and see if we can’t work together.

Your comments?

If you have science colleagues, please share this with them for their ideas for a joint solution.

Footnote; Peter Cullen “The turbulent boundary between water science and water management”. Freshwater Biology, Vol 2. Issue 1, August 1990. He was described as ‘provocative, constructive, brave and always grounded in good science’. Peter was an Adelaide ‘Thinker in Residence’ in 2004. Sadly, he died in 2008. His ideas, however, live on.

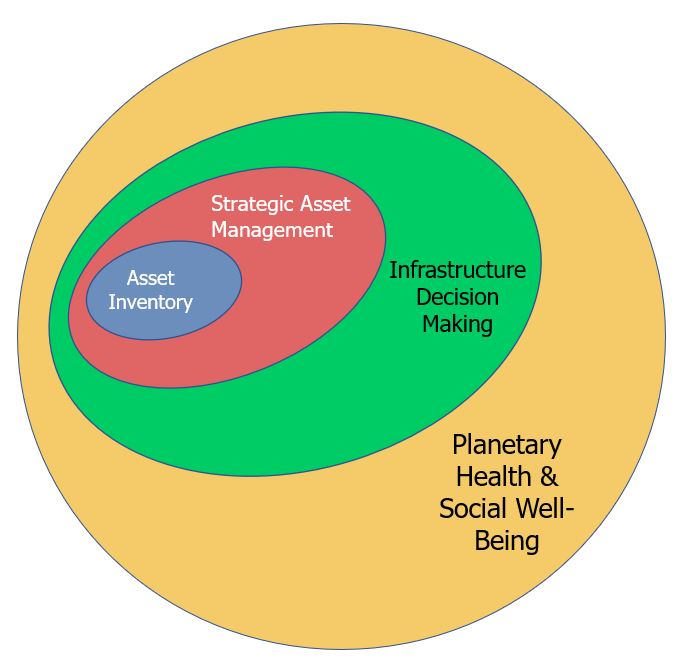

In May 2018, Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda wrote here about three ‘revolutions’ in Asset Management – later renamed ‘waves’, because that captures better the idea that one wave doesn’t supersede another.

Since then, we have discussed with each other and many others how Wave 1, ‘Asset Inventory’, is more successful if you already have in mind the vision of Wave 2, ‘Strategic Asset Management’ and how you are going to use all of the information you collect.

We have looked at what Asset Management practitioners need to develop to move on from this, to be able to look beyond our own organisations, to a bigger role in supporting our communities. We called this Wave 3, supporting better ‘Infrastructure Decision Making’.

We have even begun to imagine Wave 4.

As Penny puts it: whereas Wave 1 looked at WHAT we had, and Wave 2 looked at HOW we needed to manage it, Wave 3 started to ask WHO we were serving by our efforts. This has brought us now to start thinking more deeply about this question and about the next move, looking at the critical question of WHY.

As Asset Management practitioners, we have to ensure we are in the right positions of influence to be able to challenge existing infrastructure assumptions, which is what I think Wave 3 is all about. To look ‘up and out’, as Lou Cripps of RTD puts it.

But we can already spot that there is no point in being able to ask hard questions, if we don’t have the right questions to ask….

What do we mean by ‘better’?

“The worst misunderstandings sometimes happen between different teams within the supposedly same ethnic group, particularly if they [come] from different locations or had different professional training (say, IT workers mingling with engineers)” – Gillian Tett

I have long been fascinated by differences in approach between engineers and Asset Management professionals – how AM is not just another variety of engineering. And, for that matter, why Operations managers don’t think like AMps, or how IT teams look at the world. For instance: what is it that motivates people in IT teams? (Not, I think, the pleasures of making users happy.)

In my own life, I seem to have sharply favoured working with maintenance, or ex-maintenance people, rather than Engineers with Capital E. Because they were very different experiences.

It is not that there have not been engineers who are massively important to me, such as my brother, or my parents’ best friend Ed – but then again, they never acted like typical engineers, and were not very polite about such ‘grey men’ (Ed’s phrase) themselves. That engineering does have its own cultural norms, some quite odd, has been a question for me for many decades.

So my eye was caught by the review of a book by Financial Times editor Gillian Tett, Anthro-Vision: How Anthropology Can Explain Business and Life. About trained anthropologists such as Tett who have found themselves working in businesses, such as Google or GM, or what they would advise governments on dealing with COVID-19.

She describes how anthropology is about both investigating what’s strange, other, exotic, and about the tools to see our own culture/s, to understand what is weird (or even WEIRD) about it. The book has plenty of interesting examples – about Kit Kats in Japan become an indispensable good luck charm for school exams, about dealing with Ebola or ‘CDOs’, as well as more effective advertising and work practices.

But it particularly made me think of how to understand the oddities of current engineering – why is so often tends towards the short term, to silos and uncoordinated stupidity, even resistance to data. Surely none of those attitudes are ‘logical’ – so what is really going on? I take it as given that, like IT, there is a coherent motivation, a vision of what it means to be a good engineer. So how come… that doesn’t play nice with Asset Management, so often?

And then again… what is the culture of Asset Management, developing before our eyes?

Because I also take it that if you don’t try to understand the water you swim in, you also don’t really understand what you are doing – how it might need to change or evolve – and why it gets up the nose of others who don’t share your basic values.

There is always culture, always weird to someone outside it, and managing infrastructure involves several different ones. So we must have anthropology in our Asset Management toolkits, too!

Next: Ethnographic approaches we might use in practice?

Any maintenance or asset manager knows that the longevity of assets is critically dependent on how well they are maintained. And you don’t have to be a maintenance manager to know that your car needs regular servicing. It is kind of obvious! Yet, when it comes to the important public infrastructure on which we all depend, maintenance is considered dispensable and is the first to be cut in times of financial stringency.

It is all to do with how we account for infrastructure assets. Below is the problem – and how we can overcome it using your asset management plan and condition based depreciation (CBD).

The Problem

It pays to know a little history. When government departments and agencies adopted accrual accounting practices and had to bring infrastructure assets to account for the first time, (In Australia, from 1989) naturally they turned to the private sector, where this had been the practice for many years. And this is where the first problem arose since private sector assets such as plant and machinery are depreciated over their predetermined lifespan until they reach zero or some predetermned salvage value and then they are completely replaced.

Infrastructure assets are different. This does not happen with infrastructure assets which can be kept in service for an indefinite time by piecemeal, if somewhat lumpy, component renewal. What is the age of an asset which may have some components 100 years old and others that were renewed yesterday? What is the life of an asset that can be kept in service as long as you want it to? These are unanswerable questions. They go to the heart of the difference between infrastructure and non-infrastructure assets and require a different accounting approach.

However when infrastructure assets were first brought to account, there was no alternative accounting approach for infrastructure assets, so rather than account for the entire infrastructure system, it was decided to assign each component a definite life and depreciate it as if it were an independent asset. It seemed a practical solution to a difficult problem. But in the process it completely ignored the key characteristic of infrastructure assets which is the interdependence of the components, where the life of a component, and thus the need to renew, is dependent on the other components with which it interacts. In other words, the life of components is indefinite, as is the life of the system as a whole. This does not mean infinite! It just means that you cannot define a life of a component until it reaches the stage of renewal. So depreciation in this case doesn’t work.

You will also notice something else about this approach. The economic life of any asset, as we stated at the beginning, depends on how well it is maintained, and yet maintenance does not feature in this accounting process. This is what makes it so easy for organisations to cut maintenance, since cutting maintenance does not affect the life of the asset, at least not in the accounting system – only in the real world!

The Solution

We need a better system, one that takes equal account of maintenance (minor and major) and renewal, i.e.everything that we need to spend to maintain the functionality of the asset. (In practice ‘maintenance’ and ‘renewal’ are really just different points on a continuum.)

Why do we depreciate assets at all? It is so that we can represent reduction in asset value in any particular period (asset value = its store of future services)

Is there a better way of doing this that recognises the distinct character of infrastructure assets? There is! What better way can there be of valuing the using up of asset services than the cost of making it good again? This is what is called Condition Based Depreciation (CBD). And it is available to any organisation that has a sound, and audited, AM plan as a costless spinoff. Put simply, the condition assessment of your assets that tells you what you need to spend over the planning period to maintain service function and that is in your AM Plan. It covers maintenance, minor and major and renewal and is the cost of making good the consumption of the asset over that period. You choose your planning period and it is updated on a rolling annual basis. The cost of ‘making good’ over the planning period is then expressed as an annuity to give you an annual cost and is the best estimate of real depreciation.

Second history lesson: When the UK water industry was being privatised in the early 1980s the argument was put forward that their assets should not be depreciated because the assets were continously maintained. This was rightly rejected by the accounting profession who said, in effect, ‘prove it’ and that is what a sound, audited AM plan does. Unfortunately some do not recognise the distinction between this and the AM plan backed CBD.

CBD was introduced in 1993 and has been well received by maintenance and asset managers and by practising accountants. It was adopted by the NSW Roads authority and by about a half of NZ’s councils for about ten years (until their accounting society called a halt). It is even provided as the ‘modified’ approach in GASB 34, the standard that introduced accrual accounting into the USA in 1999 but it was rejected by the Accounting Standards Board in 2004 and nothing much happened for the next 13-14 years!

Now it is back into contention because of problems with asset valuation giving depreciation figures that are artificially high and causing councils to be deemed non-viable. These councils are now scrambling to make cuts to their budget, eliminating services and sacking staff – and all at a time of Covid 19! So fictional figures are giving rise to real – and negative – physical effects. We can do better, much better!

Would CBD help bring your maintenance to the fore?

Extra references on CBD

Condition based depreciation for infrastructure assets, 1993

Depreciation of infrastructure assets

Condition based depreciation – the questions

- Extra information is provided here.

- Ask any questions you like and I will answer all of them.

To ask questions and to find out more about a national forum to develop support for adoption of CBD, use the comments section below. (There is global interest in this subject, so we might extend it to a global forum.)

In the last post I suggested that it might be time we changed our thinking on major issues like nuclear disarmament. But perhaps it is also time we changed our ideas on how we try to convince anyone to change anything!

I am indebted to Kerry McGovern for the following idea. She spoke of a friend who had argued that when introducing a new and controversial idea, 3% of the population are already of this opinion and do not need you to tell them, 7% are almost there and can be easily convinced, and about 30% recognise that they don’t know enough but are prepared to find out, the next 30% are too busy doing other things, and the last 30% are going to oppose you no matter what. Her advice is forget that bottom 60% and concentrate first on networking with the 3%, bringing in the 7% and then, as a group addressing the next 30%. I don’t know the source of the figures but the general idea is attractive. Moreover, working on these figures, once we have captured the 37%, assuming that the middle ‘busy’ 30% are neutral, we now have a majority on our side!

So often, we focus on the bottom 60% and see the issue as an ‘us and them’ antagonistic confrontation. But what if we were to look instead at the top 40% and see the issue as one of collaboration? Would not that be generally happier and more productive?

Last year I took part in a ‘Ban the Bomb’ march. Many organisations were involved, including WILPF (The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom), and the photo above is thanks to the keen eye of WILPF’s International Treasurer, Kerry McGovern, who noticed it in an Instagram feed of hundreds of photos to celebrate the fact that the UN had reached the milestone of the 50th ratification of the UN Global Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty.

Here’s the situation

With the Honduras, 50 countries have now ratified the UN Global Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty and there was much celebration. There are 84 signatories, so 34 are still to ratify. None of the 84 have nuclear weapons. Meanwhile countries that do, like the USA, Russia, the UK, France and China, India, Pakistan and North Korea (and likely Israel) have not signed. Australia also has not signed. It does not have nuclear weapons but it does possess the uranium which makes them possible. So effectively those that have signed, even if they haven’t yet ratified, are those who have everything to gain and nothing to lose.

We are now just a few months away from the end of the ten year agreement between the USA and Russia to limit nuclear research and testing.

No wonder the world is getting nervous!

But is treating nuclear disarmament as a moral issue the most effective way forward?

It certainly is a moral issue, and ‘Ban the Bomb’ marches such as the one that I took part in last year, keep the issue in the public mind, but is this the most effective way to bring about change?

When we look at the issue clear eyed we can see that it is those who have nuclear weapons who are the most at risk, both physically and morally. They are the ones who have the difficult decisions to make, not the 84 signatories from the non-nuclear countries. And after the experience of Ukraine, a country that did have nuclear weapons but ceded them to Russia in the breakup of the USSR and then suffered the consequences, it is not surprising that those who currently possess nuclear arms are in no hurry to dispossess themselves.

So is it not time to invert our thinking?

Instead of collecting masses of signatories from non-nuclear nations, which only serves to make us feel we are doing something, when we really aren’t, perhaps we would be more effective if world organisations thought about how they could make things safer for nuclear weapons countries to dispossess, particularly for Russia and the USA.

I realise that thinking of nuclear armed nations as needing protection, rather than us being protected from them, is not the normal way of looking at the problem. But this ‘inverted’ thinking might serve us well in all of our encounters with others. It puts us all on the same side, rather than in ‘us v. them’ opposition. This idea can be used everywhere.

LATE BREAKING NEWS (FRIDAY 30 OCTOBER)

The Russian Mission in Vienna has just issued a 4 tweet communiqué which you can find at https://twitter.com/mission_rf/status/1321815042384449538?s=09 . Its complaint is valid and the results are just what you would expect when you set up an antagonistic, ‘Us v. Them’ framework. See what you think!

The 4 tweets read

- On January 22, 2021 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons will enter into force. It was negotiated without Russia or other nuclear-weapon states. (We regret) this development for the following reasons:

- We don’t see any legal gaps in disarmament process for #TPNW to fill in. It was negotiated w/out taking into account fundamental principles of #NPT. Those principles should be applied consecutively and w/out distortion

- #Disarmament should be addressed only through consensus of all parties, including nuclear-weapon-states as per #NPT. #TPNW conceptual framework is unacceptable. It ignored strategic context & addressed #disarmament separately from existing international security environment.

- (We stand) for stands for nuclear weapons-free world & respects those sharing this view. But this process can’t be forced. We reaffirm our individual & collective #NPT commitments, but #TPNW is a mistake. It creates a rift btw states & harms #NPT. We won’t support, sign or ratify it.

Recent Comments