Yesterday I was asked what question I could put before political candidates in the federal election. I sent this.

The next Global Financial Crisis

Last Friday the US 1-10 year yield curve inverted, meaning that people are now willing to accept a lower return on ten year bonds than on immediate 1 year lending, the reverse of what we would naturally expect and what is normal. This is an indication of gross market angst. Over the last 50 years, such an inversion has always been followed by a US recession within the next 24 months or so.

Such a recession could trigger global debt defaults and since debt levels are much higher now than they were at the time of the last financial crisis we can expect that the impacts will be more severe – significantly on employment, on inflation and on house prices. Whatever triggers it, we can expect that there will be another global financial crisis.

Mistakes we made last time

In the last financial crisis we attempted to control the worst effects by investing in infrastructure and construction packages, but fast tracking infrastructure led to gross wastage through hasty and poor decisions being made, and the Government later scrambled to claw back the money it had spent by reducing operations and maintenance funding – leading to further losses. We did come out of the last GFC reasonably well, but at a significant cost.

So my question for political candidates, particularly any who aspire to the position of Treasurer, is:

” What do you plan to do to stabilise the Australian dollar in the event of the next financial crisis?”

Infrastructure is more than a collection of projects

When we are faced with a GFC, the sooner we intervene, the smaller the intervention needs to be. So anything with a sizeable gestation period – like infrastructure – is a poor answer. It is often suggested that we hold a stock of ‘shovel ready’ projects (to use the American term). This is easy, but we don’t do it. And I would argue, nor should we!

Thinking in terms of ‘projects’ rather than ‘infrastructure systems’ is wasteful and unproductive. Wise infrastructure decision making is not about roads, it is about our transport systems; it is not about a hospital, but about our health systems. Infrastructure decision making requires careful planning and time to ensure that the correct integrations are made.

All of which suggests that infrastructure is NOT a good answer to short-term, stop gap, financial crises – of the local or the global variety.

So what is? Almost anything else! Anything that gets more government money into circulation and received directly by those most disadvantaged, who need to spend it straight away. Teacher’s Aides or similar would be good, for little training or equipment would be needed to get them into work, and recovery money would not be siphoned off into exports.

Thoughts?

This is the last in our ‘words matter’ series by Douglas Bartlett, Manager Asset Planning, City of Kalamunda, and member of the Perth City Chapter. Is this how you would interpret growth and prosperity for all? Doug welcomes your responses and alternatives.

Growth is a concept based on natural systems and leads to efficient forms (such as living creatures). Aside from the biological growth, there is also the ability for an individual to grow in experiences, learning, and skills, which may or may not have limits. Growth in populations can be geometric and uncontrolled, limited by resources with ‘natural’ controls via food, space, reproduction rates, predators.

Growth is a concept based on natural systems and leads to efficient forms (such as living creatures). Aside from the biological growth, there is also the ability for an individual to grow in experiences, learning, and skills, which may or may not have limits. Growth in populations can be geometric and uncontrolled, limited by resources with ‘natural’ controls via food, space, reproduction rates, predators.

Using the context of the growth of the living creature, can we change the language or philosophy behind AM ‘Growth and Demand’ such that our community and its assets is considered to be a living organism which grows to create its most efficient form? This implies that the eventual form is matched to the limit in resources. This language would replace the mathematical population growth models, that are theoretically without limit. In our modelling of course, we must place a conceptual limit to growth because at some level we are unable to imagine the size of the population.

Mexico water shortage. Filling up from water trucks.

Prosperity can include concepts of equity, opportunity for a job, a business, to eat, learn, have shelter, recreate. Prosperity is a present state measure and is measured against historical states or other communities. There is no future focus so if we adopt ‘Prosperity’ as the objective:

- we may struggle or suffer from a lack of perspective of future impacts/threats, and

- we may not be able to react to change.

When considering the change of word from growth to prosperity we must also remember that AM looks at ‘Growth and Demand’ not just growth. ‘Demand’ introduces an economic perspective whereby the price increases until the demand and price are balanced within the marketplace. In terms of AM this means people will demand more (quantity, quality, time, less cost) until a point that the service exceeds their desire to pay for it. But in reality the point we try to each is where people become comfortable (with what they have) and no longer seek or expect more. Also the community is not directly exposed to the cost of things, as they pay taxes and receive services but there is almost no direct connection between them. So: we are trying to determine the demand for services, and demand is met once people become comfortable.

Putting these ideas together: growth in a living organism, ensuring we keep a future focus, and demand reaching a level of comfort: the service provided by assets needs to be modeled so that the service is expected to grow and change form, metamorphosing into a new service that is more efficient for the community: The new butterfly effect.

‘Just the facts, ma’am’ – was a catchphrase made popular by Detective Joe Friday in the TV detective show, Dragnet. The implication was that it was he, the detective, who would interpret the facts, for we do not make decisions based on the facts, but rather on our interpretation of the facts.

‘Just the facts, ma’am’ – was a catchphrase made popular by Detective Joe Friday in the TV detective show, Dragnet. The implication was that it was he, the detective, who would interpret the facts, for we do not make decisions based on the facts, but rather on our interpretation of the facts.

Interpretations can vary widely. In 1987 when the PAC revealed for the first time, the full extent of the cost of replacing all of South Australia’s public infrastructure in South Australia, I interpreted this as a liability to be planned for so I was unprepared for the State Treasurer to thank me most sincerely for ensuring that the State retained its triple A rating! A triple A rating when it was facing a quadrupling of its asset renewal within the next 15 years and had no idea of what to do about it, how was that possible? Simple: the ratings authority had been persuaded (as, unfortunately, so had the government itself) to interpret the replacement cost of assets as the ‘value’ of the assets and, since this value exceeded the measured value of the debt (ignoring future replacement considerations), all was considered to be well.

At least if the facts are clear, we can debate the interpretation (see Evidence based decision making). But what if the facts are wilfully distorted?

The ABC reported last Thursday (June 14) that 40% of infrastructure spending is now ‘off-budget’. This translates to being invisible for most. Even Saul Eslake (the former ANZ chief economist and member of the Parliamentary Budget Office’s panel of expert advisors) is reported to have ‘only noticed the scale of such spending days after the budget lock-up, as he went through the finer details in hundreds of pages of Treasury papers”. The ABC says that he isn’t the only one now paying attention – and perhaps we all should!

The Government is effectively treating this infrastructure as a ‘financial investment’ which implies a financial return. A case of wilful blindness since most of its infrastructure spending not only will not provide a financial return but will require further commitment of resources to manage and maintain.

We need to see the facts as they are, not how they have been massaged to appear. This can happen in major cases such as the above, but also in smaller ways in our own organisations.

With infrastructure, what we choose to see – and choose NOT to see- may have serious impacts for many generations to come.

This is a case to follow.

See

The Budget 2018 Sliced and Diced.

The 2018 Budget contains hidden investment time bomb

Our January theme is ‘Getting Ready for Change’. One of the biggest changes is that infrastructure is no longer a national, but a global game.

Our January theme is ‘Getting Ready for Change’. One of the biggest changes is that infrastructure is no longer a national, but a global game.

In the last several posts we briefly looked at the issues being addressed at the World Economic Forum. But WEF is not Australia’s only major international commitment impacting our infrastructure decisions.

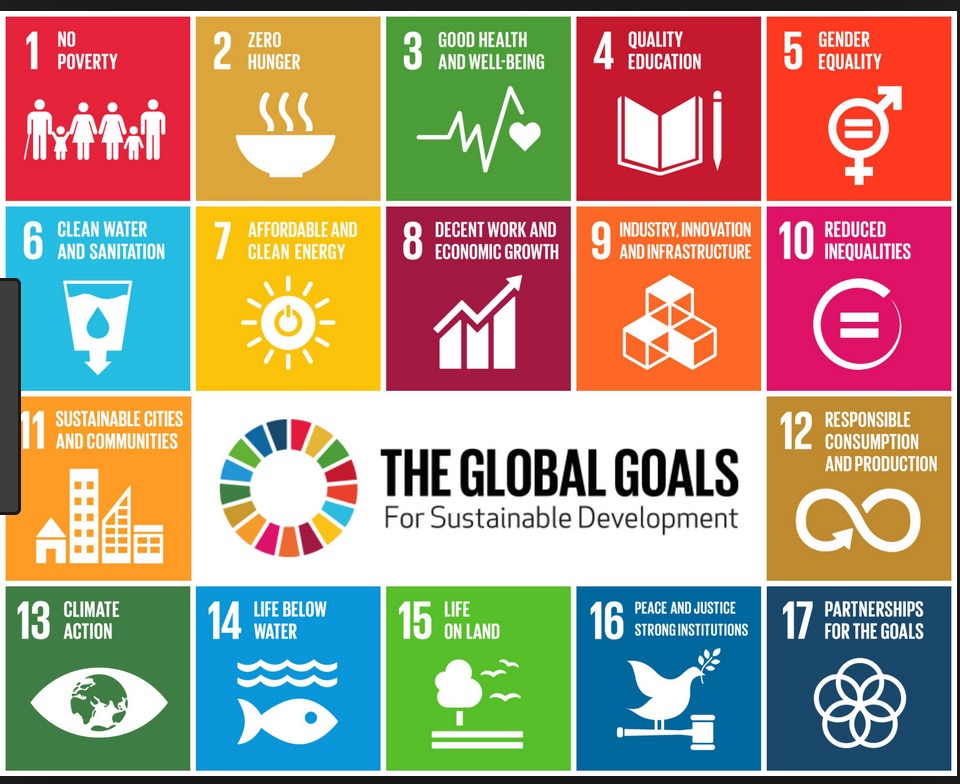

The Australian Government is also a signatory, along with over 190 other countries, to the United Nations 17 sustainable development goals, or SDGs. This requires the co-operation of all levels of government, all business and really all individual Australians. Yet how many of us are even aware of these goals?

The Senate has recently opened an inquiry into the implementation of the SDGs and we will look at this next few posts. But first, consider the goals themselves. Unlike the United Nations’ earlier Millenial Goals which focussed on developing countries, the SDGs apply to all, developing and developed alike.

One of the first steps is getting ready for change is to be aware of the global game we are now playing in.

So Three questions today:

- On an individual level: how many of the goals apply to consumption choices you make?

- On an organisational level: how many of the goals apply to the work your organisation does?

- On a government level: how many of the goals apply to the decisions our governments make (at all levels)?

If you would like to share your thoughts on these issues, please do – just click in the menu above the item ‘leave a comment’.

Filling up from water trucks. Courtesy: Planet Thoughts.

In Australia, our regional cities are struggling for lack of activity and our capital cities are at risk of becoming disfunctional, particularly on the fringes, because of too much activity! The activity I speak of is infrastructure investment.

Why are we so hell-bent on developing mega cities? Big does not mean strong. It does not mean resilient. There is a lot of evidence world wide. Consider:

A horror story – current and continuing

The problems of Mexico City. See Mexico City, parched and sinking, faces a water crisis, an interactive report by the New York Times.

Now ask yourself, what lessons could we learn from this – and how many of the problems being faced there are exacerbated, even created, by high urban densities. And if water is not enough of a problem for you, consider transport, social and environmental issues. How many of our problems do we bring on ourselves? And how could we better manage by re-directing our growth efforts?

Recent Comments