Among my personal highs and lows of 2024, the standout experience was going to Japan.

I am sorry to say I have never encountered a Japanese Asset Manager, but thanks to GFMAM I got to hear a rep from the Japanese maintenance societies at the IAM UK conference in London last month.

Despite what we hear about its economy, the country is still doing very well on total maintenance and quality in manufacturing. Some days it seems every other car on our roads is a Toyota.

And my overriding sense of Japan? That along with the incredible food and gardens and manufacturing, it’s simply the most sensible society I have ever seen.

Starting with the toilets at Tokyo airport when we arrived.

I have long suspected the most important thing about Asset Management is that it is sensible. Don’t spend where you don’t need to, but do what you must to sustain what we need to thrive. Don’t preach growth for its own sake, and be wary of ‘innovation’ (think of ‘the Maintainers’ and their 2020 book The Innovation Delusion*). What does the evidence tell us? What risks are we really running with our assets? Cut through the lobbying and classical economics – and make sensible decisions.

Sensible is not necessarily glamorous; AM is not glamorous. It doesn’t pander to fantasies, of engineering or entrepreneurs.

As several Western countries seem to lose the plot, even caught up in what can only be described as fascist dreams, it was wonderful to experience somewhere that has a much stronger sense of its limits. A lot of people in a limited space, and some of that physical space quite dodgy: how can we organise food, rub along with millions of strangers without pulling guns on each other, love nature (trees!), create beautiful things? Value education, and don’t take our gods too seriously.

Take what we need, and reject what we don’t.

Yes, I am hopelessly romantic about Japan, ever since my father worked there when I was a child. But I didn’t expect to come away with sensible.

PS not sure I will ever be happy with cold toilet seats again.

* The Innovation Delusion: How Our Obsession with the New Has Disrupted the Work That Matters Most

Note: Japan, like many countries including the UK, USA, China and France, not to mention Germany and Russia, has some dismal history. Unlike some of those countries, it appears to be able to learn from its past, but this is not to excuse its treatment of Korea and China and prisoners of war in the past.

Note: Print copies of The Story of Asset Management are available, go here and choose the direct Amazon link for your location. (and my thanks to Matthew Hughes who drew my attention to the fact that this was not at all obvious.)

A writer for the Guardian described ‘The Story of Asset Management’ as the ‘inside story of a major change’. She said: “While discussions about government reforms make take centre stage, the behind-the-scenes processes of problem-solving and innovation remain less documented” and this is very true.

I am grateful to her for this insight, for it tells me that this story of how AM grew, can also be used as a rough guide to growing any idea. I can’t say that I knew this at the beginning, but looking back, I think that there are three keys to growing an idea. 1. You have to be fully committed to your idea which doesn’t mean knowing exactly how to do it, but rather having, and believing in, a direction you want to move in. 2. You can’t expect others to do the work, you have to be prepared to do much of it yourself. 3. But while you are doing this, you must actively share the excitement, fun – and the credit – as widely as you possibly can.

As you read the many anecdotes in this story I would be interested to hear from you whether you believe this to be true. I hope you enjoy the story, simply as a story, our story. But I would be very pleased if you were able to use it fo further an idea of your own, either in asset management or elsewhere.

Penny

With the beginning of a new year, most of us are thinking about what we plan to do in 2023 – we consider our aims, objectives, goals and targets.

I am reminded of a conversation, some years ago, between Françoise Szigeti, who was then Vice President, International Centre for Facilities, Ottawa, Canada and Helen Tippett, then Emeritus Professor, Faculty of Science, Victoria University, New Zealand.

Françoise observed that the same words tended to be used to convey totally different meanings, and Helen came up with the following that she uses to help her students keep the meanings straight.

- “You AIM for the stars.

- Your OBJECTIVE is to land on the moon.

- Your GOAL is to build a rocket with enough fuel to get you there at an affordable cost.

- Your TARGET is be ready to launch in two years.”

Got It?

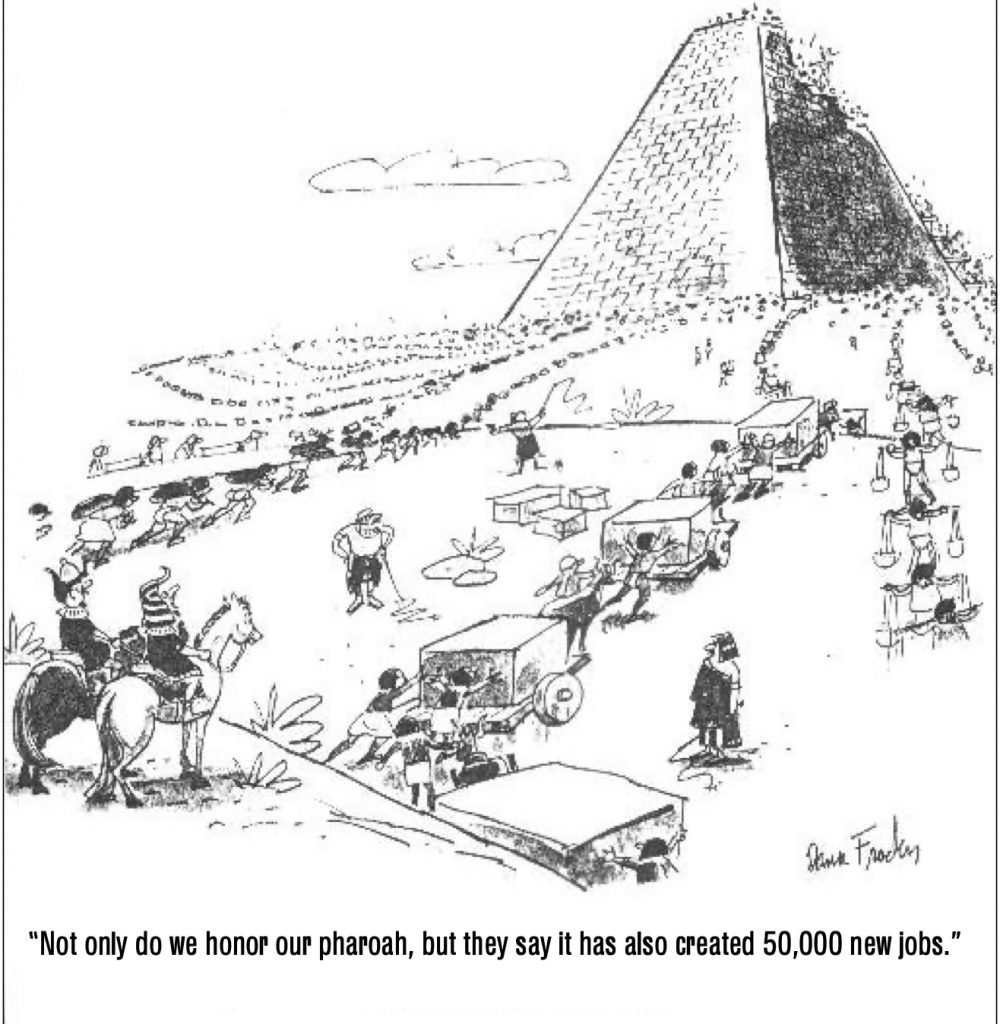

In the late 1950s, peaking in the mid 1960s, there was a great need for infrastructure as our population was growing rapidly. This was a time of full employment. We are again looking to infrastructure to get us out of the downturn that Covid has caused. But is it the ‘right’ solution now?

A little bit of history, 1950 – 1985

With its large land mass and tiny population, Australia had long feared invasion from their crowded northern neighbour, Indonesia. So, after the war it took advantage of the opportunity to build its population by encouraging both refugees and migrants. In addition to the overseas influx, the 1950s also saw the beginnings of the baby boom. Australia’s population rose extremely rapidly in a very short space of time and quickly outstripped growth in housing. At the time, two and even three families might have to share a house.

The private sector could not move fast enough so the Commonwealth took up the challenge.At the time, it was flush with funds for with women now entering the workforce in large numbers, tax revenues were greatly increasing, and with the need for social welfare very low, it could afford to spend – and it did. It created large rental housing estates, hundreds of new suburbs, all with supporting infrastructure in water, electricity, roads, etc. And so, for over 30 years, an entire generation, we experienced rapid construction growth, we didn’t know anything else.

More history, 1985 –

But by 1985, things were changing. Population growth was slowing. The Federal Government was no longer flush with funds. It was time for construction to slow down. The large expansion of infrastructure in the past thirty and more years was also presenting demands of its own. Logically we needed to consider switching our attention from growth to maintenance and over the next ten years this was to become even clearer.

But there was resistance, and it came from three sectors – industry, where the large construction companies built up during the building boom did not wish to see demand for their services reduced; politicians, who saw growth in State GDP and constant infrastructure announcements as proof of their ability to serve the people; and the construction professionals themselves, whose numbers greatly exceeded the fledgling asset management professionals.

With the change in history, came a change in justification for construction

With population increase slowing, and so much infrastructure now completed, we could no longer justify major construction by reference to urgent need – so we changed the justification. It was now argued that infrastructure ‘created’ employment. Many still believe that this is so. But actually, it is public spending that creates jobs – no matter where it is spent, on infrastructure – or on services.

We are also now rethinking ‘the goal’ for infrastructure.

What do you think the goal for infrastructure should now be?

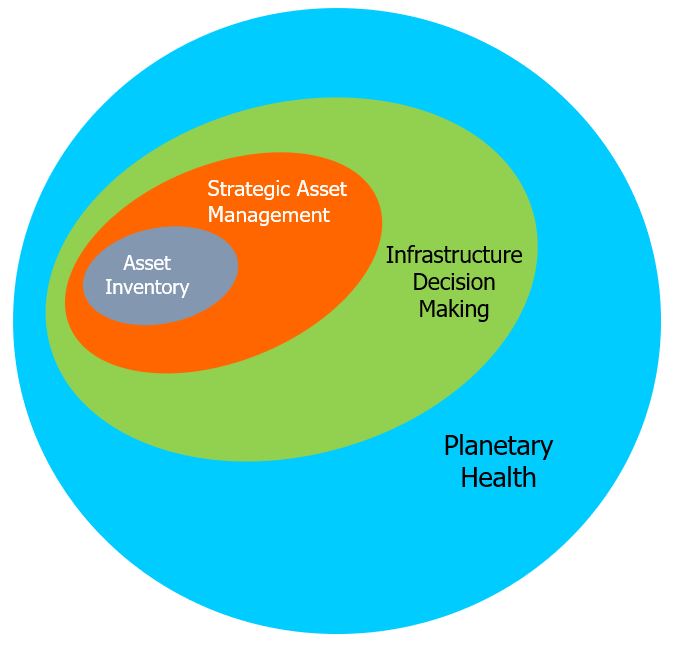

In a previous post, there was a diagram showed how each of our ‘waves’ could also be conceived of as particles, embedding and building on each other. .This is our latest version, to capture the ideas of ‘grey assets’, as opposed to green and blue assets.

For the last 40 years the economic focus has been on growth.

And so infrastructure decisions have also focused on growth. But now this growth focus is changing as we realise the damage we are causing – and so asset management and infrastructure decision making needs to change, too.

We are now at a pivot point.

We have been at pivot points before. This is what Talking Infrastructure’s THE ASSET MANAGEMENT STORY is now documenting.

At each pivot point in Asset Management (the beginning of each wave), we have expanded our understanding of the world we operate in. Starting from simply maintaining and recording in Wave 1, we moved, in Wave 2 or Strategic Asset Management, to using this information to optimise decisions concerning our existing portfolios.

Then, in Wave 3, we look to take on a bigger role, infrastructure decision making, where we go out into our communities to work on whether the size and shape of our portfolio is what it needs to be. Wave 4 extends our understanding of our asset portfolios to the impact we are having on society and planetary health, and actively seeks to improve these impacts. The task in Wave 4 is to make all infrastructure decisions ‘future friendly’.

Wave 4 is the challenge that Talking Infrastructure was surely set up to address.

It is our most critical pivot point yet in asset management. This is the challenge that Talking Infrastructure CEO, Jeff Roorda, is leading at the Blue Mountains City Council where he is Director of Economy, Place and Infrastructure services. The city’s focus is on Planetary Health and Social Wellbeing. And we will be reporting what the City, and others with whom it is working, learns so that everyone can move in a saner direction than we may have done in the past.

If this interests you, watch this space, for a new series of blogs about infrastruture and biodiversity.

And, of course, become an active part of the dialogue on Talking Infrastructure.

For your weekend reflection over a cold beer – or libation of choice.

In 1999 my friend and colleague, @KC Leong, organised the first AM conference in Malaysia. It was held in Kuching, Sarawak. Not only was asset management very new but even the concept of an asset was pretty new so that the Minister opening our conference felt that he needed to explain what an asset was. ‘An asset’, he said, ‘is anything of value’. Then he paused, thought for a moment, and added ‘ and also anything not of value’ for, he explained ‘ it could become of value later’!

But what does it mean to be ‘of value’ ? This is something that we started exploring last weekend. I learnt a lot from our discussion and sincerely thank @Adam.Lea-Bischinger, @Gosh Jacewicz, @Ruth Wallsgrove, @Gregory Punshon, @Christopher Silke for their contributions. What this showed, is that we cannot simply assume that all infrastructure is (a) ‘of value’ and (b) certainly not ‘of equal value’. So how do we decide what projects should get our attention?

Today I would like to take this further by considering some of the arguments presented by Mariana Mazzucato. Mariana is an Italian-American economist whose research into the eocnomics of innovation and the high technology industry revealed that far from the private sector being the wellspring of all innovation, nearly all of the significant innovations that are now in common use (and just about all of the features of the iPhone) were actually developed in the public sector. She does not detract from what the private sector has done with these innovations but she does bring out the importance of state investment, which has featured so heavily, especially in the early, high risk stage, so necessary to subsequent development. In her first book ‘The Entrepreneurial State’ she debunks the myth that the State is merely a dull and stodgy administrator and shows that much of the real innovative work is done in the public sector.

Consider Australia’s own CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation). From its development of wifi using complex mathematics known as ‘fast Fourier transforms’ as well as detailed knowledge about radio waves and their behaviour in different environments, to Aerogard developed way back in 1938 and now used by Mortein to protect us from disease producing insects. Its research beginning in 1968 resulted in the world’s first plastic banknote which protects against forgery. This basic research was carried out by the CSIRO as part of the public sector. Now required to finance itself, the CSIRO has less scope for basic research (which is expensive and so hard to fund in the market) and has instead to focus on applied research. Which is all well and good, but where are the next basic research breakthroughs to come from? Is this an example of short run gain at the expense of long term loss?

A similar problem arises if we focus on the infrastructure that ‘supports the market’ rather than infrastructure that ‘supports the community’. In her 2017 book ‘The Value of Everything’ Mariana argues that modern economies reward activities that extract value rather than create it and that this must change to ensure a capitalism that works for us all. For those of you who would like a quick insight into her work, I would recommend the article in ‘Wired’(with thanks to @Rohan Fernandez who introduced me to her work via this article). She also has some fascinating TED talks on Youtube.

I have selected just three questions today from Mariana’s 2019 Ted Talk ‘What is economic value and who creates it?’ (which is worth watching, she packs a lot into 18 minutes), but you may add (and answer) other questions that you think relevant to infrastructure decisionmaking. The important thing is that we thing about these things, because if we don’t the choice will not be ours, and may be to our dis-benefit.

- Who are the value creators? Who is not creating value? (e.g. who are just extracting value, or taking it from someone else; and who are actually destroying value?) Who are these people?

- What is the difference between productive and unproductive activity?

- When agriculture was the dominant output, land was considered to be the major ‘source of value’, when we reached the industrial revolution, capital became the dominant source. Now as Mariana shows when we focus on ‘preferences’ the source of value becomes rather vague. How does this impact our infrastructure decisions?

What other questions do you think we need to think about when considering value?

I look forward to hearing your ideas

Have a great weekend!

Photo by Tembela Bohle from Pexels

As we head into another hot January weekend in Australia, here is something to ponder while you drink that cold beer! (or something warmer if you are in the Northern Hemisphere!) Does Infrastructure HAVE value? Does it CREATE value?

What is value?

In 1981, at the height of the Michael Field’s Labor Government’s attempt to bring Tasmania back from the brink of financial catastrophe caused by excessive over borrowing, I was approached by a Minister with a request. He expressed it most diffidently. ‘If you are not too busy, could you tell me what is value?’ I gave him a mini economics tutorial on the subject which he clearly understood, but equally clearly, it did not get at his real problem. For the rest of the week I pondered on this question for it was particularly intriguing that he had prefaced his question by the statement ‘A number of us in the house have been wondering’. Now, one minister asking about value is interesting, but a whole group doing so struck me as quite unusual.

The Source of value?

After a few days, I figured the stimulus for the discussion of value at a time when major cuts were being made to all portfolios, could be that each Minister was simply trying to establish that his department was ‘too valuable’ to have its budget cut. So I wrote a small, humorous, playscript in which various Ministers (of invented portfolios to avoid angst) argued for being the major ‘source of value’ – calling on economic, historic and social support for their case. My Minister was delighted and distributed it to his cabinet colleagues. I had concluded that script by observing that ‘fragrance free soap’ could fetch a higher price than that with fragrance and looked at ways in which each minister could increase value without imposing a cost to the budget simply by removing elements that had ‘negative value’.

Relevant Again

I had not given more thought to this question in the almost 20 years that followed until recently reading Mariana Mazzucato’s work on ‘The Value of Everything’. Just as an understanding of value was critical to that financially strapped Tasmanian Cabinet, so it is also critical to those of us involved in deciding on the shape of future infrastructure and we will look at Mariana’s ideas from this viewpoint in future posts. But, just to get the ‘little grey cells’ working, here are some basic questions to consider.

- What do you understand by value? How do we measure value when considering infrastructure projects?

- Can something that has no price be ‘of value’? For example can private education (with a price) be valuable, yet public education (free) not be? (Some years ago the Head of a major accounting association declared that private schools were assets yet public schools liabilities – purely on the ability to make a cash return. What do you think of this?)

-

Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian

Can something that has a high price not be ‘of value?’ E.g. recently a banana stuck to a wall with a piece of ducktape at Art Basel in Miami Beach was sold at a price of $120K -and not once but three times. It has created a firestorm of comment and brings to the forefront the idea of ‘value’.

- Can cost be a good proxy for value? And if we substitute a more costly (although not necessarily more effective) component, does this really represent an increase in value – as distinct from simply an increase in cost?

- Pharmaceutical companies like to price their products in terms of outcomes -such as the value of better health? Should they be allowed to appropriate all of the beneficial outcomes. Why or Why not?

Do add your comments and we will examine them further next Friday.

Enjoy your weekend!

Just before my father died, he drove to visit me, then cheerfully walked down the road to have a haircut. He had been mostly bedridden for over a year and it was hard to recognise in this strong and happy man, the person I knew to be so ill. Within days he was in hospital and a week later he was dead. I found out later that this last burst of energy from a dying person is not at all unusual.

As with people, also with ideas?

As I watch the attempts of politicians to promote the use of coal fired generation, I think the same may apply to ideas. The fight for the dying idea of fossil fuel generation is so strong with some that it seems to outweigh all the death indicators, like the facts that solar is now far cheaper as well as environmentally more sustainable, that banks are not interested in supporting new construction and insurers are withdrawing their support.

And Rail?

What other examples can we see around us? I am a train buff. I enjoy travelling on trains, especially the London and Sydney tube lines, and my library contains many books of rail journeys and videos documenting the development, operations and maintenance of underground rail, so it hurts to think that this latest burst of rail construction might be another death rattle. However with the arrival of trackless trams, automated driving, and potentially reduced demand with greater use of video conferencing, and increases in the number of people working from home rather than central city offices (despite increased populations), one has to ask the question. On any rational assessment the need to cope with a rapidly changing future would seem to argue in favour of transport infrastructure that is lighter and more adaptable.

And yet the rapturous reaction to the proposal of a Melbourne Suburban Rail Loop, with hardly a voice raised in opposition, challenges this rationality. How much of this support is fuelled by the heady expectation that, with the rail loop, Melbourne will become another ‘London’ with all the status that implies? How much is it because we are familiar with this means of transport and therefore can easily visualise such a future whereas other options are perhaps still in science fantasy land? At this stage, these are just questions.

Professor Graham Currie

So I am greatly looking forward to my interview this Friday with Professor Graham Currie on the Melbourne Suburban Rail Loop. Professor Currie is Director of Monash Infrastructure, Chair of Public Transport, and Professor in Transport Engineering. He is a renowned international Public Transport research leader and policy advisor with over 30 years experience. He has published more research papers in leading international peer research journals in this field than any other researcher in the world.

(I don’t know whether this impresses you, but it impresses the heck out of me!)

Professor Currie is also founder and Director of the Public Transport Research Group at Monash University which was identified as the 3rd top academic research group in the world in an European independent review of the field in 2015.

I could go on about his numerous best paper awards and countless other achievements, but you get the picture. This is a person who knows what he is talking about when it comes to public transport.

You will be able to hear this interview on the September episode of our podcast.

YOUR CHANCE TO ASK YOUR QUESTIONS

If there are questions that you would like me to put to Professor Currie – be quick, put them in the comments section and I will do my best.

PS For those in Melbourne

If you would like to join us for AM exploration on the theme of how AMgrs can support their organisations in a changing future, be advised that Monday and Tuesday morning are now full but we have three spaces left Tuesday afternoon, 30th July. Email me at penny@TalkingInfrastructure.com – but do it quick!

“Private firms efficiently finance their operations or they fail”

Clifford Winston, Brookings Institution.

There are a lot of implied assumptions here! Where do we start?

A major implication is that private firms must therefore be more efficient than public firms, but this makes a massive assumption – namely that the losses to the community from those private firms that fail is of lower consequence to the community than inefficiencies of public sector organisations that are not allowed to fail.

Where has this ever been rigorously and neutrally examined? And if it had – why would we have persisted so long, throwing good money after bad, at the UK private sector firm, Carillion? Carillion, which employed 43,000 people to provide services in defense, education, health and transport, collapsed in January, becoming the largest construction bankruptcy in British history. It left creditors and the firm’s pensioners facing steep losses and put thousands of jobs at risk

We tend to regard as heroes those entrepreneurs that go bankrupt – perhaps many times – and then come back and make a fortune. That latter fortune, however, is financed (involuntarily) by many small entrepreneurs and their families, some of whom may well have gone out of business because the work they did for our bankrupt hero was never paid for.

There have recently been a number of very large and very public failures in the banking system that have created enormous public havoc. These banks cannot ‘go bankrupt’ but can – and are – bailed out by the public, which is the equivalent. Without this ‘safety net’ and the incentive to make a profit ‘no matter what’, would a public banking system, such as we once had, have fallen prey to the sub-prime mortgage debacle?

Have the so-called ‘efficiencies’ created by a private banking system been systematically weighed against the costs? I suspect that this is an area where we are acting in ‘blind faith’. It has to be blind because there is so much to the contrary that we can see if we but look.

Another aspect of this faith is the presumption that anything that we may say in favour of private sector or ‘market‘efficiency’, still holds true when the private sector is propped up by government contracts (e.g.public toll road contracts).

I am not arguing that there are not problems in the public sector. There are. But would it not be an idea to address these problems directly rather than advocate private provision where there are also problems – but they are less amenable to correction?

When are we going to get that definitive examination of Carillion and hold them responsible?

Our Situation

The world is running out of raw materials and fresh water and is being overburdened with waste and the global construction industry is a major contributor being the largest consumer of resources and raw materials of any sector, responsible for about 33 per cent of emissions, 40 per cent of material consumption and 40 per cent of waste.

Our Challenge

In seeking to deal with this by advocating carbon neutral cities and a “sustainable” built environment, David Ness says that all the talk is about increasing efficiency of operational energy (heating, cooling, lighting) and reducing associated greenhouse gas emissions.There is a failure to account for resource consumption and “embodied carbon” in our buildings and we need to take this problem seriously. We need to find better ways to “reduce, reuse and recycle” in the construction industry. For anyone in doubt about the seriousness of this situation, look up the Guardian’s Concrete Week, five consecutive articles about the dangers of concrete as a construction material and major landfill component.

Our Question

How can we curtail this excessive resource consumption and waste production and protect our quality of life?

Our Guide to Action

And make no mistake, the size of this problem and the extent of the misery that we will experience if we do not solve it, means that we must all take action – as consumers and producers, as users of buildings and infrastructure and as those who write the policies that allow continued abuse or generate potential improvements.

In ‘The Impact of Overbuilding on People and the Planet’ (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019) David A. Ness provides a guide to action, following the recommendations of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, Johannesburg, 2002, ‘which affirmed that all countries should promote sustainable consumption and production patterns by establishing a “sound material-cycle society”, in which the consumption of natural resources is reduced and environmental impacts are minimised. In both developed and developing countries, the key to achieving this was seen to be the promotion of the 3Rs (i.e. reduction, reuse and recycling of waste) in addition to ensuring the sound disposal of waste.’

David’s ideas are backed by years of research in Australia, Asia and especially China – and they are new, innovative, but also practical! “If we can make use of and adapt existing building and infrastructure stock, we save new carbon and resources,”

Practical Application

“We also need to design any new structures for ease of disassembly, adaptation and reuse, as part of a ‘circular’ built environment.” And to put this into practice he has been working with Arup. .

In 2017, the UniSA research team, of which David is a lead player, was awarded the Arup Global Research Challenge to further pursue his ideas. Part of the New Royal Adelaide Hospital was selected as a test case, with radio frequency identification tags attached to potentially reusable building components such as partitions, ceilings, doors and facade panels, and information such as location, size, type, and age of those components uploaded to a database. This successful ‘proof of concept’ opens the way to the next step – some commercially viable applications. It shows there’s an opportunity here to re-use systems that were previously sent to landfill or at best recycled for their raw materials,

The project has allowed the team to take advantage of relatively new technologies like BIM (Building Information Management) systems and cloud-based database storage systems to help track, categorise and organise building elements in a way that was never before possible.

What can you do?

There are many ideas in this book that you can combine with the latest technology if you are research inclined. But for me, the major impact of the book is on global mindsets. What we have for long taken as natural, normal, and indeed beneficial – that is, ever more building and construction – ‘more cranes in the skyline’ – are not natural, and we need to consider carefully whether the benefits they provide are worth the damage that they inevitably cause. This is not to say we should not build more, just that we need to do more to establish whether any particular proposal is of NET benefit.

For all who have a social and environmental conscience and concern, read

The Impact of Overbuilding on People and the Planet’ by David A Ness.

Recent Comments