Thinking about Waves 3 and 4 of Asset Management, this quote from a recent novel struck me:

“It is difficult for anyone born and raised in human infrastructure to truly internalize the fact that your view of the world is backward.

“Even if you fully know that you live in a natural world that existed before you and will continue long after, even if you know that the wilderness is the default state of things, and that nature is not something that only happens in carefully curated enclaves between towns, something that pops up in empty spaces if you ignore them for a while, even if you spend your whole life believing yourself to be deeply in touch with the ebb and flow, the cycle, the ecosystem as it actually is, you will still have trouble picturing an untouched world.

“You will still struggle to understand that human constructs are carved out and overlaid, that these are the places that are the in-between, not the other way around.”

– Becky Chambers, A Psalm for the Wild-Built (Monk & Robot Book 1), 2021

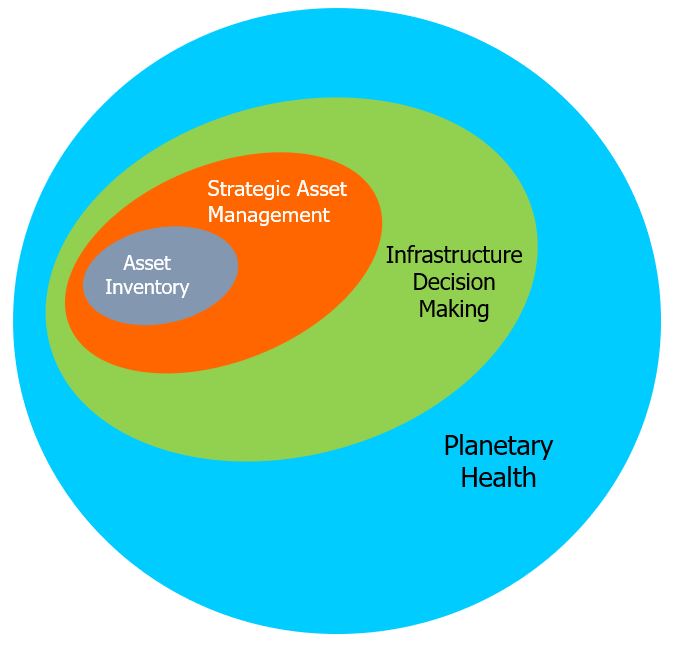

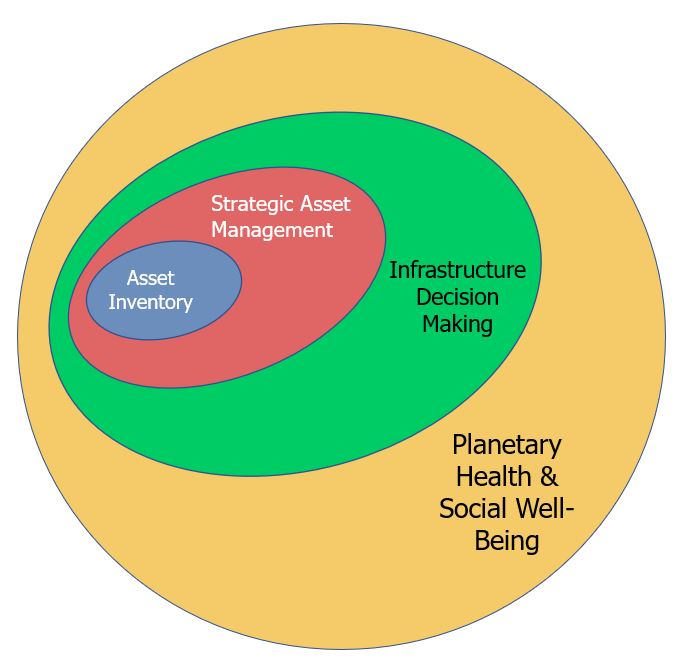

In a previous post, there was a diagram showed how each of our ‘waves’ could also be conceived of as particles, embedding and building on each other. .This is our latest version, to capture the ideas of ‘grey assets’, as opposed to green and blue assets.

For the last 40 years the economic focus has been on growth.

And so infrastructure decisions have also focused on growth. But now this growth focus is changing as we realise the damage we are causing – and so asset management and infrastructure decision making needs to change, too.

We are now at a pivot point.

We have been at pivot points before. This is what Talking Infrastructure’s THE ASSET MANAGEMENT STORY is now documenting.

At each pivot point in Asset Management (the beginning of each wave), we have expanded our understanding of the world we operate in. Starting from simply maintaining and recording in Wave 1, we moved, in Wave 2 or Strategic Asset Management, to using this information to optimise decisions concerning our existing portfolios.

Then, in Wave 3, we look to take on a bigger role, infrastructure decision making, where we go out into our communities to work on whether the size and shape of our portfolio is what it needs to be. Wave 4 extends our understanding of our asset portfolios to the impact we are having on society and planetary health, and actively seeks to improve these impacts. The task in Wave 4 is to make all infrastructure decisions ‘future friendly’.

Wave 4 is the challenge that Talking Infrastructure was surely set up to address.

It is our most critical pivot point yet in asset management. This is the challenge that Talking Infrastructure CEO, Jeff Roorda, is leading at the Blue Mountains City Council where he is Director of Economy, Place and Infrastructure services. The city’s focus is on Planetary Health and Social Wellbeing. And we will be reporting what the City, and others with whom it is working, learns so that everyone can move in a saner direction than we may have done in the past.

If this interests you, watch this space, for a new series of blogs about infrastruture and biodiversity.

And, of course, become an active part of the dialogue on Talking Infrastructure.

In May 2018, Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda wrote here about three ‘revolutions’ in Asset Management – later renamed ‘waves’, because that captures better the idea that one wave doesn’t supersede another.

Since then, we have discussed with each other and many others how Wave 1, ‘Asset Inventory’, is more successful if you already have in mind the vision of Wave 2, ‘Strategic Asset Management’ and how you are going to use all of the information you collect.

We have looked at what Asset Management practitioners need to develop to move on from this, to be able to look beyond our own organisations, to a bigger role in supporting our communities. We called this Wave 3, supporting better ‘Infrastructure Decision Making’.

We have even begun to imagine Wave 4.

As Penny puts it: whereas Wave 1 looked at WHAT we had, and Wave 2 looked at HOW we needed to manage it, Wave 3 started to ask WHO we were serving by our efforts. This has brought us now to start thinking more deeply about this question and about the next move, looking at the critical question of WHY.

As Asset Management practitioners, we have to ensure we are in the right positions of influence to be able to challenge existing infrastructure assumptions, which is what I think Wave 3 is all about. To look ‘up and out’, as Lou Cripps of RTD puts it.

But we can already spot that there is no point in being able to ask hard questions, if we don’t have the right questions to ask….

What do we mean by ‘better’?

A new world, new questions

Today is the 5th Anniversary of Talking Infrastructure. It was created in July 2016 to consider the new world we are now in – and the new questions this world and its challenges requires.

It is now massively evident that whereas a focus on competition to secure the success of individuals and individual companies has generated much that we enjoy today, it has also generated serious problems, of which climate change and social inequity are just the most visible.

Infrastructure – problem or solution?

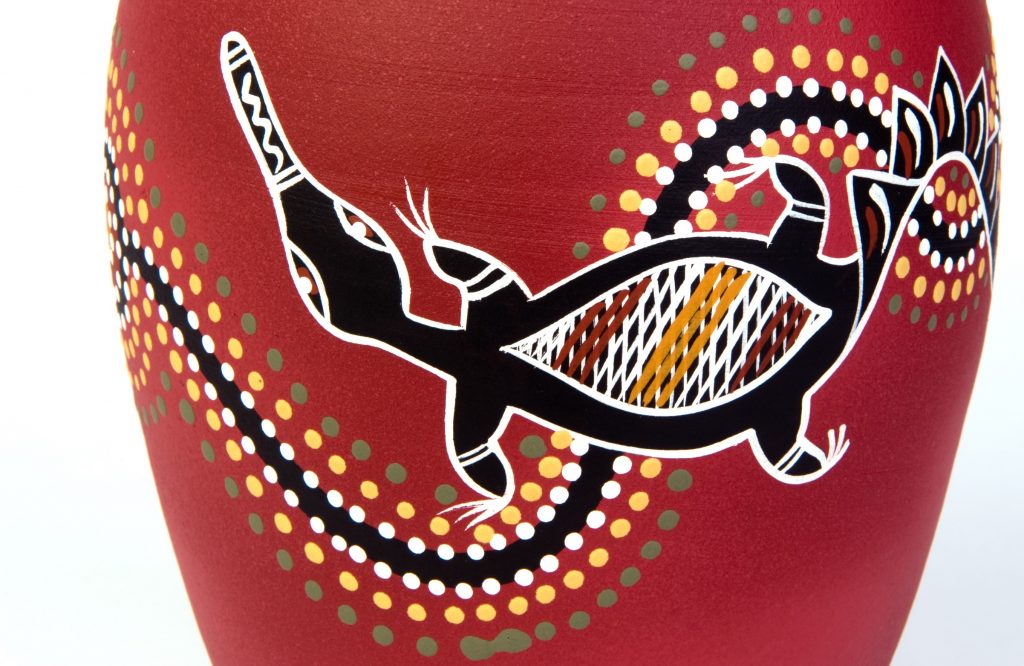

While we may be reluctant to admit it – infrastructure has been a large part of the problem! Every infrastructure does considerable environmental damage. And not every infrastructure generates commensurate community benefit. A few months ago, I said’ Goodbye to our Talking Infrastructure Guy’, – and explained what was wrong with our current attitudes to infrastructure. Today he is formally replaced as our icon.

So welcome our new icon – the Australian platypus – symbolic of the collaboration we so badly need. The platypus was originally regarded as a joke, for it was considered an impossibility, being so many different animals all in one. And this version of the platypus reflecting our aboriginal culture is particularly appropriate. The Australian aboriginals are the oldest civilisation in the world sustaining the land for over 50,000 years. That’s resilience! And they have done it by a focus on community, rather than self, and a veneration for the land that supports us.

If we want a future that will support our children and theirs, we need to embed these iconic qualities of community, resilience, and sustainability in all of our decisions – and especially in our long term infrastructure decisions – from new and renewal to ongoing maintenance and even to eventual withdrawal.

What questions do we now need to ask ourselves in order to secure this future?

Hint: They are not the questions that we started with in asset management and which I discuss in volume 1 of our series, The Story of Asset Management. Consider the ten questions I pursued in the first 10 years (1984-1993) which you can find here Or, to see the questions in context, see “Asset Management as a Quest – contents”.

After you read these questions, consider to what extent we have already solved (or at least know the solution to). Then ask yourself what the questions for the next ten years should be.

And, if you would like to see how I came up with these questions to start with, you may enjoy the first chapter of “Asset Management as a Quest” which you can find here. The full volume will be available in the New Year.

What do you consider the most important questions? Please add them below.

Dreamstime.com/ 187958062 © Meg Forbes

The world of infrastructure Asset Management has had the benefit of an evolutionary model for several years: the ‘Waves’ of Penny Burns, to make sense of how organisations seem to have to go through a period of focus on basic information (Wave 1, Asset Inventory) before they really look at how to use it to make better decisions, to start optimising (Wave 2, Strategic Asset Management).

Before that, I confess, I struggled to express what was going on: how could people get stuck in data and databases? I don’t know that I fully understand, still, but I least I recognise it now – that having a list of all your assets, simple facts like install date and location, and a big dumb database to put it all in preoccupied so many of us for so long.

Penny herself seems not to have spent too much time worrying about this, but always had a vision way beyond it. She assumed we would have a grip on lifecycle costs, thinking longer term, and planning ahead, and get down to acting smarter on our asset decisions.

And now, as we work together to capture our collective history and development, we are really looking forward to the next Wave. To really so much better infrastructure decision making that is fit for purpose, through the rest of this turbulent century.

Look out for celebrating our history on July 29th!

Dreamstime.com/ 38357225 © Bogdancaraman

One thing that puzzles me in the world is the desire of many to be more excited by what technology could do to emulate people than about people themselves. Why are Asset Management conferences packed with papers about data, and usually silent about what human beings bring to decision-making?

Even those who should know better (because they have been there) talk about ‘data-driven’ processes; and organisations pour far more money into dumb databases than getting a better understanding of their assets.

I suspect this is partly the fetish for capital over on-going costs – and, frankly, ideological faith that it’s better to invest in ‘innovation’ than labour costs. Anything that promises to cut staff is good, no matter how much it costs to try to replace them.

Now, I am a big sci-fi fan, which generally accepts the forward march of technology. But then again, it also warns about how it can wrong, at least in the stories I read. I am not at all sure replacing people with robots benefits anyone, and not the 99% of us that don’t control how automation is used. I am not especially optimistic.

However, there is one thing I am pretty certain about, even in embracing uncertainty about the future: no-one really has any clue about how we can replace experience in managing physical assets.

I remember when I first noticed that investment in things like work management systems, or even more basic computerised processes, could lose sight of how things really work. Big IT in the 1990s in asset-world was sold as replacing some administration costs – mostly part time, middle aged women, who cost almost nothing as they were paid very little, who managed the monthly reporting, knew where the data was, what it meant to asset decision makers, and what to do with it. And the local nerds who programmed in Fortran in their spare time, and wrote routines for their next door colleagues to do any analysis or maths required.

At least we might try to learn the lessons from the history of IT: where did it work, and why?

Which, to me, includes the question of how to think of technology as a tool to assist skilled people. Why would we even want to see ourselves replaced?

In writing Building an Asset Management Team, Lou Cripps and I looked at the skills an effective Asset Management team requires – both technical and business understanding, good grasp of front-line experience, both system and structured thinking, a longer term perspective, emotional intelligence and communication skills, embracing uncertainty and the tools to think about risk, integrity, and enough leadership ability to get others to buy into a new way of working.

Good infrastructure Asset Management requires a tricky combination of attributes.

Lou came up with the image of the platypus, that is very rare and not to be found on most continents.

Instead of searching for an amphibious, duck-billed, otter-footed, egg-laying, venomous mammal that locates prey through electroreception, it’s easier to provide all the qualities we need through a complementary team.

But we still love platypuses. Watch out for more of them in the next ten days!

The Innovation Delusion: How Our Obsession with the New has Disrupted the Work That Matters Most, Lee Vinsel and Andrew L Russell (September 2020)

Is this the first ‘popular’ book on Asset Management & Infrastructure Decisions? You wouldn’t necessarily know from the title.

But maintainers and asset managers are the, well, not heroes here: Vinsel and Russell describe ‘infrastructurers’ as something better than heroes. ‘The people who care about things’, as Lou Cripps puts it. And infrastructure in terms of human rights.

The book is a sustained attack on ‘bright, shiny new things’, especially when they really are not worthy of the name innovation, and when they will land communities in debt and ‘deferred maintenance’ for many years.

“Although you wouldn’t know it from histories that fixate on innovation and inventors, much of human history is, in fact, stories of stability: of how societies coordinate labor to maintain the large-scale public systems we’ve relied on since ancient times.”

But the authors are not simply academics, or popularisers. With Jessica Myerson, the authors have set up The Maintainers, https://themaintainers.org/connect. Their vision is:

“Through collaborative efforts across an interwoven network of communities, we pursue our mission of maintaining self and society through reflection, research, and advocacy in the hopes of achieving a more caring and well-maintained world.”

The book itself is a good read, using the current ‘popular’ non-fiction style of stories around individuals: everything you’ve ever worried about with poor rail track maintenance and failing water systems, and some good people trying to sort them.

I suspect it’s generally true that, when you know the inside story, things are not always quite as simple as written. I was a ‘fly on the wall’ at PG&E over the time of Camp Fire, and I don’t buy that wildfires should be blamed on ‘somebody else’, or one company’s profits alone, for example.

But, with honourable mentions for reliability engineers, Ursula K Le Guin, Melinda Hodkiewicz, and even ISO 55000 – and even computerised maintenance management systems! – this is my kind of territory.

Your reviews of it are most welcome here.

And what do you think about essential infrastructure as a basic human right?

Jos van Ouwerkerk, pexels.com

People like us who are responsible for managing public infrastructure assets always leave a legacy. Good or bad, that depends on how well we do our jobs now.

Famously politicians, along with billionaires, are attracted to the idea of a shiny new asset with their name on it. They see themselves remembered and honoured every time anyone drives down a road named for them. But this is often not true.

Firstly, if the road is poorly designed and badly maintained, no-one will be honouring your memory.

Secondly, if this puts the community into long-term debt, or wrecks other community benefits such as a stream or potential for other services – anything that will prevent them from doing what is needed in future: this is a poor legacy. Even if not everyone remembers it was your doing, they will not think kindly about whoever was responsible for such short-sightedness.

Thirdly, by definition, it is a poor public servant who puts their own ego against the needs of their community.

What would be a good legacy?

What would you like to leave for future generations?

Photo by Marcus Spiske, from unsplash.com

‘I wish it need not have happened in my time,’ said Frodo.

‘So do I,’ said Gandalf, ‘and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.’*

What do envy and the attitudes of some people responsible for infrastructure at this time have in common?

Wishing things were different, instead of getting down and actively working to change things.

This was prompted by a conversation last week with an Asset Manager struggling to get their executive to stop moaning about how unlucky it all is, and start planning for what’s going to be needed going forward from Covid-19. People paid a goodly amount of money to take responsibility, who instead are acting like victims: everything would have been ok, if only….

Wanting the world on your own terms is not a strategy. Managing assets is for life, not just for Christmas, not just the good times.

It made me think again how vital the principle of honesty is for good infrastructure management. Chris Lloyd and Charles Johnson in their Seven Revelations of Asset Management (Assets, May 2014) put it like this: Asset Management demands openness about past performance. We have to face up to what’s gone on before, how well (or how badly) the assets are doing.

But we also have to honestly face up to change – even when it looks calamitous. That is what responsibility means.

Even discussing the deadly sins soon comes round to Asset Management!

The serious point is how we build up that sense of responsibility, in ourselves and in top management, to do our level best with what we have taken on. To commit to be better informed, better trained, to learn from best practice and to live it.

No-one forces anyone else to involve themselves in crucial infrastructure. You do not have to apply to be CEO of a public service, or run for election to the Council – but, having made that choice, it’s not a cushy number.

*J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

Recent Comments