Today’s post is by Jeff Roorda, Technology One, and Deputy Chair of Talking Infrastructure.

Is using condition to determine life a fundamental error in asset registers?

Part 1

How long does an asset last? The answer determines life cycle cost, depreciation and infrastructure planning.

Asset registers estimate useful life for every asset but which life do we use? The physical life or the economic life? Yes these are different, and often materially different. I recently was working in Queenstown NZ with Queenstown-Lakes District Council. After work, I boarded the steamer TSS Earnslaw that had been carrying passengers on lake Wakatipu since 1912, and its steam engine is still powered by coal. The Earnslaw and many steam powered transport assets around the world still have many years of remaining physical life after over 100 years of operation.

So why did we stop using steam for transportation ? Was it because the assets reached their physical life?

In hindsight we all know the answer. Because steam power is dirty and technology made steam power obsolete. OK then, so the economic life was determined by function and capacity, not by physical condition. Even though steam powered assets had many years of physical life remaining, they became obsolete relatively quickly, far more quickly than most people managing the assets predicted. How much of the infrastructure we are building right now will be obsolete well before physical life is reached? So why do we focus on the measurement of physical life using condition instead of function and capacity? The pace of change could be faster now than in the 1940’s and 1950’s when transport shifted from steam to the internal combustion engine which created the infrastructure networks we now manage.

Think about what we are building now and drivers for change.

Infrastructure based on continuing the past where everyone has to travel to the office at the same time creating peak transport loads using internal combustion engines with one person per car does not seem to be a likely future with changes in communications and energy technologies.

Part 2 coming shortly.

Just over a year ago (Jan 6 2017), I wrote about ‘Pop Up’ Prisons, more accurately called ‘rapid build’. Rapid build is used in war zones where there is a sudden and urgent need. It is extremely expensive. Overcrowding of our prisons had led to this now being considered an urgent need, but why had we not foreseen it? One answer had, in fact, been earlier suggested by Mark Neasbey in his post “Infrastructure decisions we make when we don’t think we are making any”(Aug 12 2016) where Mark had brilliantly, and entertainingly, explained how the ‘costless’ decision to put more police on the streets to combat crime had cost consequences which were not only extensive, but, unfortunately, invisible in the eyes of decision makers.

Just over a year ago (Jan 6 2017), I wrote about ‘Pop Up’ Prisons, more accurately called ‘rapid build’. Rapid build is used in war zones where there is a sudden and urgent need. It is extremely expensive. Overcrowding of our prisons had led to this now being considered an urgent need, but why had we not foreseen it? One answer had, in fact, been earlier suggested by Mark Neasbey in his post “Infrastructure decisions we make when we don’t think we are making any”(Aug 12 2016) where Mark had brilliantly, and entertainingly, explained how the ‘costless’ decision to put more police on the streets to combat crime had cost consequences which were not only extensive, but, unfortunately, invisible in the eyes of decision makers.

Now, today, comes news from America where incarceration rates have increased 500% over the last few decades. Philadelphia in Pennsylvania is even more extreme, their incarceration rates have increased 700% in the same time. But that is already changing with the appointment a few months ago of a civil rights lawyer, Larry Kranser, as the new District Attorney who is taking extreme action to reduce the cost and human damage involved. The whole encouraging story can be found on the Slate website here but I would like to draw your attention to one move which could effectively be used more widely.

“In a move that may have less impact on the lives of defendants, but is very on-brand for Kranser, prosecutors must now calculate the amount of money a sentence would cost before recommending it to a judge, and argue why the cost is justified. He estimates that it costs $115 a day, or $42,000 a year, to incarcerate one person. So, if a prosecutor seeks a three-year sentence, she must state, on the record, that it would cost taxpayers $126,000 and explain why she thinks this cost is justified. Krasner reminds his attorneys that the cost of one year of unnecessary incarceration “is in the range of the cost of one year’s salary for a beginning teacher, police officer, fire fighter, social worker, Assistant District Attorney, or addiction counselor.”

The same reasoning could be applied to just about any new rule or regulation introduced by government.

Comment?

This is a brief account of a lengthy 2014 dialogue I had with Patrick Whelan, a thoughtful architect in WA. You are now invited to join the discussion.

This is a brief account of a lengthy 2014 dialogue I had with Patrick Whelan, a thoughtful architect in WA. You are now invited to join the discussion.

Patrick: In WA, a scoring model was devised and adopted for all police buildings, It scored building fabric condition and the condition of services to determine an overall condition score. The building’s suitability for purpose was then determined by comparing scores for compliance with the Building Code of Australia and for compliance with the Police Building Code (the agency’s accommodation standards) Comparing the Condition score with the Suitability score enabled a ‘works priority score’ for the station, in effect displaying a level of service offered by each station.

Penny: Whilst building condition and code compliance are important, they are important from the perspective of the building maintenance manager. To get at the idea of service perhaps we need to look at what the building user wants to get out of the building. A building may be in excellent condition and meet all code conditions, yet still fail to work efficiently for the user. It may be that the design is no longer suitable for the new work that needs to be carried out, or it may have the wrong capacity – either too much or too little. It may be in the wrong place!

Patrick: In the case of the WA Police, their Building Code articulates everything needed of a building to progress policing: Planning criteria, technical criteria, functional relationship diagrams, room data sheets, formulae for calculating room sizes and the number of ablutions facilities, guidelines for the compliant design of custodial facilities, etc. The Police, being a paramilitary organisation, have a very strong handle on what is needed to do the job. However, things change over time, and the building code changes with them.

Penny: Building codes are so efficient because, in the short term, people only need to respond, ‘on the dotted line’, as it were: they don’t have to think. However can what makes for short term efficiency lend itself to longer term ineffectiveness? What can be done to determine a code that is both efficient and effective?

Over to you!

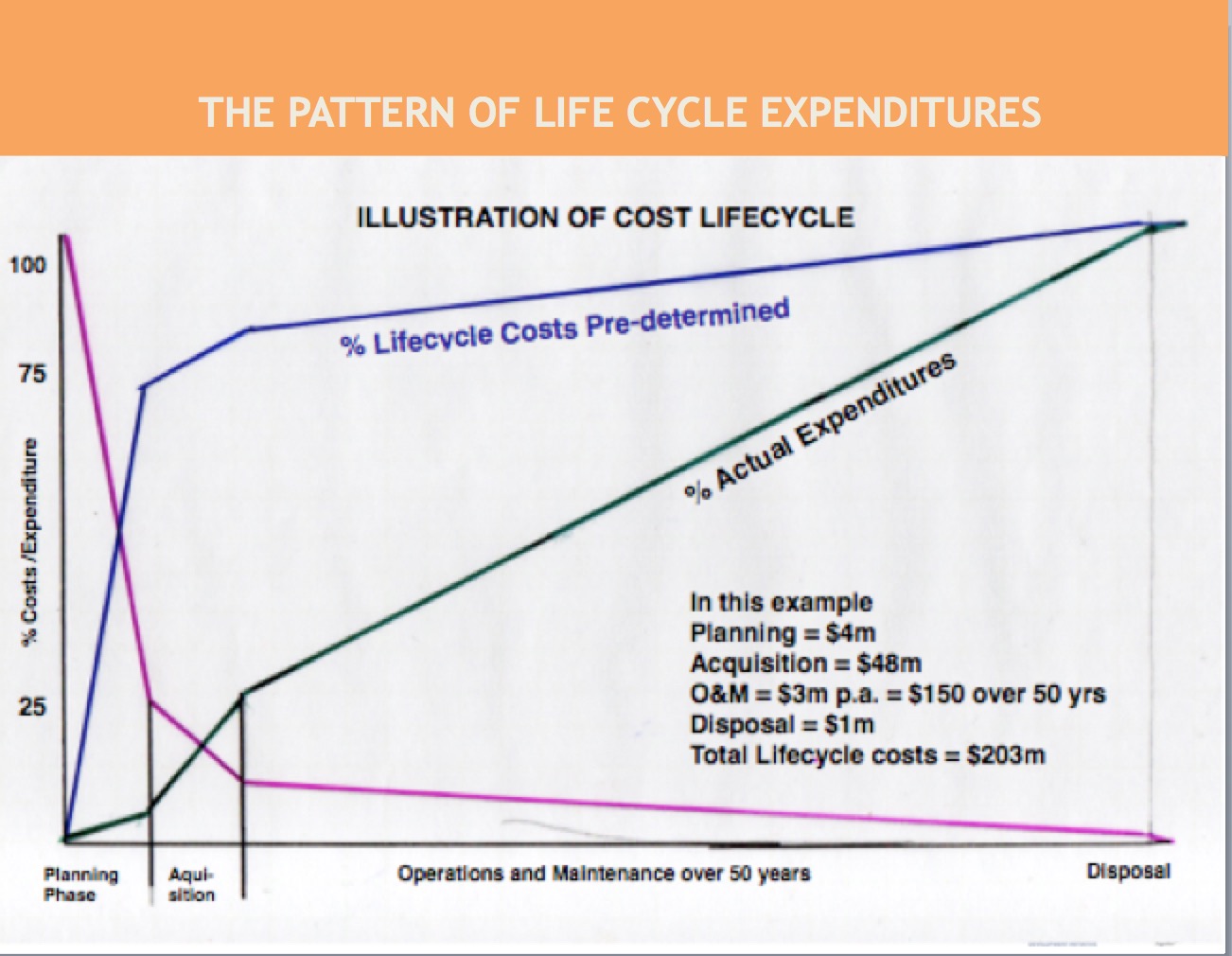

18 months ago I had the pleasure of co-designing and presenting a capacity building workshop for Auditors-General in the Pacific Islands. The subject of the workshop was auditing for the better management of public assets. We looked at the 4 stages – planning, construction,operations & maintenance and, finally, renewal or disposal – and discussion revealed that the auditors chose to spend the bulk of their time in analysing performance at the operations & maintenance stage. This made sense. It is by far and away the area where most expenses occur. However, it is not the stage where most expenses are committed. That occurs much earlier, at the planning stage. This is the stage where the nature, location and size of the project are determined and these are the primary determinants of how much will be spent later at the operations and maintenance stage.

I drew up a hypothetical schema to make the point. It showed that, by the end of the first or planning stage, only $4m of the total life cycle costs ($203m) had been spent BUT, the decisions made during this phase had already committed about 75% (and sometimes more) of the total costs. In the diagram the green line represents costs actually expended, the blue line costs pre-determined and the purple line represents the scope remaining to make a difference to total costs. This shows that by the time the plant is commissioned and operational, there is really relatively little that can then be done to improve on the overall life cycle costs.

The figures I used in this example are fictitious.

They are consistent with the theory and principles of life cycle costing as shown in the major textbooks on the subject.

I would have liked to use real figures but I couldn’t find any. So I contacted people who might be expected to know – key academic figures in asset management, experienced consultants, long time practitioners. But no, no-one could help.

So my question today is:

Why do we have so little actual data about this very key and critical stage of decision making? And how can we improve our knowledge – and thus our performance?

In the last post “The Infrastructure Quiz” I asked what the ‘purpose’ of infrastructure is. What did you choose? If you ask this question of most people, the answer is obvious – it just isn’t the same answer for everyone!

Have a look at the following possibilities:

- For asset managers, the answer is obvious – it is to provide needed services that underpin the economy and society well being.

- For economists in the Treasuries, the answer is equally obvious – it is to kickstart the economy. (For many years we had a stop-go policy for infrastructure. Whenever the economy got overheated, governments would cut back on infrastructure spending, and whenever it slowed down, they would spend more. There was a period in the early 2000s when this was recognised for the damage it caused. But now it seems to be back again.)

- Politicians and Think tanks are the ones likely to claim that infrastructure – ‘increases productivity’ and ‘raises the standard of living’ (but they seldom spell out exactly how, for it is all regarded as self-evident.)

- For the general public (most of whom could not give any examples of infrastructure beyond roads, if that) the answer is that the purpose of infrastructure spending is to ‘create jobs’.

- Military and strategic planners often see the construction and location of infrastructure as a strategic control problem. Many politicians do the same.

- The construction industry and its lobbyists strongly believe that we not only need infrastructure to keep the industry afloat but that we need to forecast what infrastructure and where in order to enable them to plan.

So, many purposes – all ‘self evident’!

In the last post Jim Kennedy, Asset Management Council, looked at what it took to construct a ‘defensible budget’. He argued that stakeholders (customers, community, government, employees) are everything but he wondered whether organisations really understood what they were promising. In other words were they really clear about the consequences of their decisions and promises made?

In the last post Jim Kennedy, Asset Management Council, looked at what it took to construct a ‘defensible budget’. He argued that stakeholders (customers, community, government, employees) are everything but he wondered whether organisations really understood what they were promising. In other words were they really clear about the consequences of their decisions and promises made?

Capability to deliver

For example, had they turned these promises into the capability to deliver (technology, plans, people, facilities, information systems, logistics, support systems).

This has two aspects: there is an ‘enabling or inherent capability’ and an ‘organisational design, or organisational capability’. In other words, the equipment may be able to deliver, but has the organisation the right people in place?

Studies have shown that where someone was sent in to fix a problem who did not know what needed to be done, was not familiar with the asset or problem, or was not fully competent to do it, the level of competence was only 50% . This led to the job needing to be done 5 (!) times more often than if a competent knowledgeable person had done the job initially with 100% competence.

But what is the organisational implication of this? To ensure that you have the right level of competence ready when needed, you have to have highly competent (and thus well rewarded) people under-occupied so as to be available when needed. As we cut back on training because it is expensive, and aim to have everyone fully engaged all the time in order to ‘achieve efficiencies’ – what is the real cost? If we cannot demonstrate the benefits of organisational capability in a ‘defensible budget’, costs will increase and quality decline.

Comment?

We often take pride in our ability to ‘make do’ when the situation is not as we would have liked. This particularly applies to those occasions when we do not get the budget we requested. We grizzle – but we ‘make do’. But what message does this send? Jim Kennedy, speaking at an Asset Management Council Chapter Meeting in Adelaide warned of the dangers of this ‘make do – can do’ culture. When we ‘make do’ (usually by cutting corners, or deferring activity that results in larger costs later) we are telling the finance section that our budget request was overblown. When Finance subsequently provides less than requested (working on the basis that the initial request was ‘gold plated’) and the recipients subsequently ‘make do’, that does more than confirm the initial Finance suspicion, it creates a lack of trust on both sides. Budget proposals are now ‘boosted’ to allow for the inevitable cuts. Finance reduces the budget request and as it goes on, budgets lose their informational, decision-making, value.

We often take pride in our ability to ‘make do’ when the situation is not as we would have liked. This particularly applies to those occasions when we do not get the budget we requested. We grizzle – but we ‘make do’. But what message does this send? Jim Kennedy, speaking at an Asset Management Council Chapter Meeting in Adelaide warned of the dangers of this ‘make do – can do’ culture. When we ‘make do’ (usually by cutting corners, or deferring activity that results in larger costs later) we are telling the finance section that our budget request was overblown. When Finance subsequently provides less than requested (working on the basis that the initial request was ‘gold plated’) and the recipients subsequently ‘make do’, that does more than confirm the initial Finance suspicion, it creates a lack of trust on both sides. Budget proposals are now ‘boosted’ to allow for the inevitable cuts. Finance reduces the budget request and as it goes on, budgets lose their informational, decision-making, value.

Jim proposes that the value proposition for Asset Managers should be “How to protect your leader against political opposition” and his answer to this question is a ‘defensible budget’.

So what is a ‘defensible budget’? Jim describes it as follows:

- Fact and Risk Based

- Fully traceable to the asset’s output requirements.

He reckons these two are really sufficient but could be bolstered by showing that the budget is

- demonstrably good practice and in accord with national standards; *compliant with statutory and regulatory imperatives;

- implemented by competent (certified) staff;

- supported by verified technology (information decision systems);

- transparently and verifiably costed (which builds up trust between the technicians and finance; and

- deliverable in the agreed time frame (don’t promise what you cannot deliver).

Good stuff! – but, and here’s the rub – developing good practice, ensuring competent (certified) staff, establishing sound information decision systems, demonstrating transparency and ensuring deliverability does not happen overnight. It takes years of consistent management attention and good leadership.

Question this week: Do you know where your organisation stands on each of these facilitators of sound and defensible budgets? Is there a program to improve it? Comment?

Editor: You can find earlier posts on budgets, by using the search function, and all posts by Mark by selecting his name.

Further to my earlier posts about asset budgets, I couldn’t help but want to have another go at this by asking a slightly different set of questions. These relate to the principle of transparency.

Further to my earlier posts about asset budgets, I couldn’t help but want to have another go at this by asking a slightly different set of questions. These relate to the principle of transparency.

By transparency I mean:

Is there a clear and documented basis for the estimates upon which the asset budget has been based?

- Are the estimates based on ‘simple’ or ‘averaged’ projections of expenditure rather than ‘modelled’ projections that emulate realistic timings and patterns of expenditure for the nature of the works involved and how they will be procured?

- Is it based on estimates for all assets over the full period that the budget is meant to address? By all I really mean a schedule that lists all of the assets, including those for which a $NIL expenditure is forecast for the relevant period. (I ask this as a check that all assets have been given consideration.)

- Are the underlying assumptions documented and made clear to those being asked to approve the budget – especially the reliability / sensitivity of rates used and associated finance costs?

- Are the priorities inherent and sequencing / pace of the proposed works also made clear and demonstrably aligned with corporate business and services priorities for the forecast period? How does this align with projected cashflow requirements and funding availability? (A projection showing a skewed acceleration of expenditure towards the final quarter must raise concerns – not only about reliability of delivery, but also in relation to business and services priorities being effectively supported, and in relation to getting value for money from what is going to be spent.)

- Are the risks that are inherent to the portfolio and the proposed program delivery made clear and ‘current’ for the immediate and forecast context of the program and its delivery?

If these aspects are not transparent to the decision-makers then there is greater risk that the program will not be delivered and the budget will be nowhere near accurate

A hole in your budget needn’t be the end of the road!

In the previous post we looked at a city council’s response to a sudden $60m hole in its budget – and the consequent media storm. Could this have been treated differently?

Put yourself in the City Council’s situation. Faced with a sudden $60m hole in your budget through external circumstances, what are your options?

- You can cut back on services (but these are services that the community want and that you have already prioritised into your budget)

- You can borrow (and borrowing might be a short term option to maintain service continuation but only if there were expectations that the external cut would be reversed in the near future or that other revenue increases could be anticipated)

- OR, and this is the option that the City adopted, you could withdraw the funds from your fully owned subsidiary – in this case BC Hydro – in exchange for a city asset portfolio (city street lighting).

BC Hydro now needs to make a return on the assets it has bought and so it engages in a forward contract to maintain, operate and supply street lighting services to the council.

Bear in mind, that any profit made by BC Hydro reverts to its shareholder – the City Council. If the costs of the contract are greater than the costs that would have been incurred by the City if it had retained ownership of the assets, then this will be reflected in a larger profit made by BC Hydro. Conversely if the contract costs are less than the City would have otherwise paid, it saves on ratepayer funds but (unless BC Hydro can run the streetlighting more cost effectively) it will receive a lower return on its BC Hydro shareholder funds.

OK, so these are the financial facts. The transaction enables the City to continue providing all the services that its ratepayers want and expect in the face of a sudden hole in its budget caused by the withdrawal of provincial funding. Out of one pocket into another but the same city coat! This being the case, why did the question of how much that was paid for the contract become the major story?

I would suggest that there are a number of lessons to be learnt here:

- The City could have sold this as a smart solution to the problem of continuing needed community service in the face of sudden withdrawal of funding by the Provincial Government. It could have promoted the idea of BC Hydro being in a better position to cost effectively manage street lighting given its expertise in lighting and power generally. It could have used this problem to market the value of its ownership of BC Hydro. In other words, on a PR basis, it could have got out in front of the story. But it didn’t. Instead it hid the contract details for 5 years before eventually acceding to Freedom of Information requests. Whatever the facts of the case, this action itself makes the council guilty in the eyes of the public.

- The public generally have very little understanding of the ratio of ongoing operations and maintenance costs to the initial capital costs. If we don’t tell them – in ways that they can understand – their natural reaction is to see the annual payments in the light of (exhorbitant) interest payments.

- The time to generate this greater understanding is BEFORE you need to use it to substantiate council decisions

- In all likelihood, the councillors (and perhaps senior staff members) did not understand the full import of operations and maintenance costs either. Their reaction in hiding the costs from public view suggests that they did not believe they were defencible.

Lesson 1 may not apply to you now, but Lessons 2-4 will always apply.

Comment: What are you doing to ensure this level of understanding of O&M is generated in your council and staff (or in your senior management and board)

Should I jump?

In 1993 a very successful American bond trader gathered together a few of his disciples and a handful of super-economists and set up a new hedge fund company that promised to be different from anything that had gone before. The new company apparently genuinely believed that their ingenious computer models would allow them to bet on the future with near mathematical certainty. Because their team had some high powered players – including two who were to be future Nobel Prize winners – investors believed them. The company portfolio grew quickly to $100 billion when a default in Russia set in train a sequence of events that the models had not anticipated. This placed the whole financial system at risk and the Federal Reserve quickly called in Wall Street’s leading bankers to underwrite a bailout. Roger Lowenstein in “When Genius Failed” (Fourth Estate. 2002) tells the whole fascinating story.

How could anybody – let alone the super intellects in that hedge fund company – possibly believe that a computer model, no matter how finely tuned, could predict ‘with near mathematical certainty’ future stock markets (which, after all, reflect the volatility that Keynes referred to as ‘animal spirits’). How could investors clever enough to have amassed the funds to invest, believe them!

Pondering these questions, I thought of the managers I have met who so passionately believe in their models that they brook no doubt, no exploration of better ways, no questioning – and I thought of the problems that this causes. Possibly it starts because to get financial backing in the first place, either from your organisation or from the market, you need to assume and project confidence.

However, confidence is one thing, blind confidence completely another.

So my question for you today is: How do we transit from the confidence we need to be persuasive before the project is adopted, to the level of confidence we need, after the project is adopted, that allows some room for doubt enabling resilience when the world changes (as it certainly will)?

Recent Comments