Photo by Steve Johnson from Pexels

Building an AM Team is like creating a piece of abstract art. What makes it work? The choice of colour, shape, positioning, the passion? All of this, and more! A practitioner’s eye and experience definitely counts. This month, Talking Infrastructure is running excerpts from a new USA guide to Building an Asset Management Team, co-written by one of TI’s long-time collaborators, Ruth Wallsgrove, together with Lou Cripps, who heads up the Asset Management Division at the Regional Transportation District in Denver. It will be available shortly – and we will let you know when and how to get hold of it.

One: Building an Asset Management Team

‘Building an Asset Management Team’ is intended as a practical guide for any infrastructure agency interested improving overall Asset Management. It is our response to common questions around staffing to perform the functions and competencies required to support an effective Asset Management system.

Asset Management carries the flag for good asset stewardship, the responsibility that comes with managing critical infrastructure assets. We owe this to current and future generations.

‘Planning brings the future into the present

so we can do something about it now.’

This includes understanding the intergenerational liabilities that are delivered with all longer life assets, and that once something is gone, it can’t always be replaced. We cannot take a better future for granted; we need to work hard each day to bring a better future into reality.

We have to stop making asset decisions in silos, and start to join up the dots. For example, a decision to electrify a bus fleet has to be made with the full understanding of the interdependencies between fleets and facilities. The type of propulsion system in buses isn’t a decision that can come from strategic planning or engineering alone.

A basic question for AM practitioners is: And then what? We build a shiny new rail line. What is it going to take to operate and maintain it successfully and sustainably for the next fifty years or more? We buy a new fleet: how will it interact both with the other assets and systems we already have, and with our existing skills and processes?

The Challenge

The challenge for US Transit Agencies, and other sectors wanting to implement Asset Management, is finding the right people and assigning committed resources to its delivery.

Asset Management is increasingly important – yet there are few

experienced AM practitioners, and even fewer useful resources

on how to develop an AM team.

The thirty years since Asset Management began to be established in Australia and New Zealand – and much less time in many places – is not long to establish a stream of trained and experienced people. AM is still not taught at undergraduate level, and only partially on a few post graduate courses up until now. It isn’t included in the standard curricula of business, finance, engineering, urban planning or other relevant disciplines.

The demand for Experienced AM teams is increasing

Add into these the now legislated requirements in North America for Asset Management, such as Ontario Regulation 588/17, or the US Federal Transportation Administration TAM rules, that require at least knowledge of it in those regulated organizations, and the demand wildly outstrips supply for anyone with any AM experience.

This guide is based on our personal experiences; it reflects the views of us as authors rather than representing our employers, any institution or the wider AM community. Neither of us could write this document alone.

If you are

- developing a business case for setting up an AM team,

- establishing a team,

- considering where to locate an AM team in the organizational structure, or

- wondering how to find and attract the staff you need.

this guide will be invaluable.

To come:

- Why you need an AM team

- What are the key activities of an AM team?

- What kind of people does an AM team need?

- What is required of an AM lead?

Today’s Asset Management Strategists

Today’s Asset Management Strategists need to ask new and different questions. We can no longer rely on answers that served us well in the past, nor the questions that generated those answers. We need to develop new question asking skills and explore new directions.

Over the last 30 years we have concentrated on efficient production, or ‘getting the job done right’ and done really well with that. Now we need to tackle the next task ‘getting the right job done’.

With so many technological options now opening up, and economic, social and environmental demands, as well as public and governance attitudes changing so rapidly- it may be a very, very, different job!

But it doesn’t have to be overwhelming.

We just need to know where to start.

In my last post I reflected on the public service in the late 1980s where I rejoiced in finding many others willing to co-operate in problem solving – before ‘competition’ rather than ‘collaboration’ became the ethos of the day.

However, there are now signs that the tide is again turning, so can we provide a vehicle for collaborative discussion? Let’s try!

Melbourne Workshops

I will be in Melbourne at the end of this month to conduct interviews for our podcast series and while I am there, the Talking Infrastructure Melbourne Team is organising a series of free workshops (coffee provided!) to explore new questioning techniques.

Here is what is on offer – Two hour workshops will be held at the Istana next to the Queen Vic Markets between Saturday 27 and Wednesday 31 – In the comments section, tell us what interests you and we will send you session times and more detail.

1. Inverse Hypotheticals

In an ordinary hypothetical a hypothetical story is created and panelists are asked questions. In an inverse hypothetical, a story is again created BUT it is the panelists who get to ask the questions. The set up is this: A review group has to consider a certain infrastructure proposal or situation. The panel are advisors to this review group and feed them the questions they feel relevant. The facilitator may throw some unexpected new items into the mix as the discussion develops.

2. Development Session: Exploring the role of the Future Asset Management Strategist

If you know the technique of ‘Beyond Bullet Points’, this is a great opportunity to practice. If not, it is a great opportunity to learn. And to produce something valuable in the process.

3. Exploration Session: “The 2020 Infrastructure Challenge”

Those of you who have been involved in asset management for a while will remember The International Asset Management Competitions which took place between 1996 and 2000. They were designed to put asset management, if not on the map, at least high on the priority list of CEOs. And it was very effective in giving asset management greater traction at that time. The 2020 Infrastructure Challenge is looking at how we might do the same for the new infrastructure decision making we will need as we transit for 20th to 21st century infrastructure.

4. Open Discussion Session

Key concerns of asset managers today, Come with your question and/or come to get involved in the ideas of others.

Not in Melbourne?

Workshops are being planned for other cities. At the moment we are looking at Sydney in mid August (while I am over Sydney way to give the opening keynote to the Asset Management for Critical infrastructure Conference, August 20th)

There is something about wet and windy overcast conditions that brings on reflection, which, if we are not careful, can lead us into melancholy. Avoiding this risk requires us to take action – and so I am. Read on to see the reason – and the action.

The way things were

In 1982 I moved from the University where academics were closely focused on their own projects, to the state water authority where – at that time – the focus was improved community outcomes. If I had an idea for improvement, it was not difficult to find half a dozen bright, well intentioned others, to willingly and co-operatively work through it with me. And, equally, there were many others willing to involve me in their ideas for improvement. The Public Service was a great place to be in the early 1980s. It changed, of course, with the introduction of modern commercial management ideas. And, ultimately, not for the better.

The way things are

This started the exodus of those who believed in community service and of the intelligent who could easily secure positions outside the government. Today, with short term public service contracts, there is no devotion to improved community outcomes – how can there be when one’s own short term outcome is so precarious, so insecure? There is also no corporate knowledge and information to draw upon. The community has lost out. The public service has lost out. Who has benefitted from this much vaunted ‘improved management’ shift?

The way things can be

Clearly I am not advocating for greater inefficiency, but I think we could do with improved effectiveness. I miss those days when community focus was the norm amongst the brightest and best. A time when, if I had an idea for allowing unprofitable irrigation farmers to sell those most valuable asset – access to water – to others who could make better use of it; or if I wanted to see whether the hype about the value of the Grand Prix could be proved, I could draw on the expertise of others simply by asking for it. That was how we started a review of irrigation water licences and put together academics and public servants to produce ‘The Adelaide Grand Prix’ – an analysis of the first Grand Prix in Australia in 1985. This was the first serious analysis of the impact of a Special Event, it has been cited in every publication on Special Events since then, and our approach was adopted by the Commonwealth Government in their grant assessments for many years – despite the hyped up arguments of some of the top management consulting companies. It prevented our State Government from following its earlier wish to contend for the Commonwealth Games – and thus avoided the ‘white elephant’ structures associated with these events.

Action now

Is it possible to replicate today those productive, well intentioned, discussions that served the greater good? I think it is. The growing strength on the non-private, non-government ‘Civil Society’ supports this. I also think it is essential that we develop a core of intelligent strategists to help manage the infrastructure shifts that will be necessary as we transit into a digital, increasingly complex, future.

Talking Infrastructure is looking to provide opportunities for those of you, from whatever disciplinary background, who aspire to be these future strategists, to physically get together with like-minded others for the purpose of sharing your ideas for improvement and assisting them in theirs – and in general developing your strategic ability to assist your organisations face the future. Does this interest you?

More information to come.

“Private firms efficiently finance their operations or they fail”

Clifford Winston, Brookings Institution.

There are a lot of implied assumptions here! Where do we start?

A major implication is that private firms must therefore be more efficient than public firms, but this makes a massive assumption – namely that the losses to the community from those private firms that fail is of lower consequence to the community than inefficiencies of public sector organisations that are not allowed to fail.

Where has this ever been rigorously and neutrally examined? And if it had – why would we have persisted so long, throwing good money after bad, at the UK private sector firm, Carillion? Carillion, which employed 43,000 people to provide services in defense, education, health and transport, collapsed in January, becoming the largest construction bankruptcy in British history. It left creditors and the firm’s pensioners facing steep losses and put thousands of jobs at risk

We tend to regard as heroes those entrepreneurs that go bankrupt – perhaps many times – and then come back and make a fortune. That latter fortune, however, is financed (involuntarily) by many small entrepreneurs and their families, some of whom may well have gone out of business because the work they did for our bankrupt hero was never paid for.

There have recently been a number of very large and very public failures in the banking system that have created enormous public havoc. These banks cannot ‘go bankrupt’ but can – and are – bailed out by the public, which is the equivalent. Without this ‘safety net’ and the incentive to make a profit ‘no matter what’, would a public banking system, such as we once had, have fallen prey to the sub-prime mortgage debacle?

Have the so-called ‘efficiencies’ created by a private banking system been systematically weighed against the costs? I suspect that this is an area where we are acting in ‘blind faith’. It has to be blind because there is so much to the contrary that we can see if we but look.

Another aspect of this faith is the presumption that anything that we may say in favour of private sector or ‘market‘efficiency’, still holds true when the private sector is propped up by government contracts (e.g.public toll road contracts).

I am not arguing that there are not problems in the public sector. There are. But would it not be an idea to address these problems directly rather than advocate private provision where there are also problems – but they are less amenable to correction?

When are we going to get that definitive examination of Carillion and hold them responsible?

The Senate Inquiry – and Political Reactions

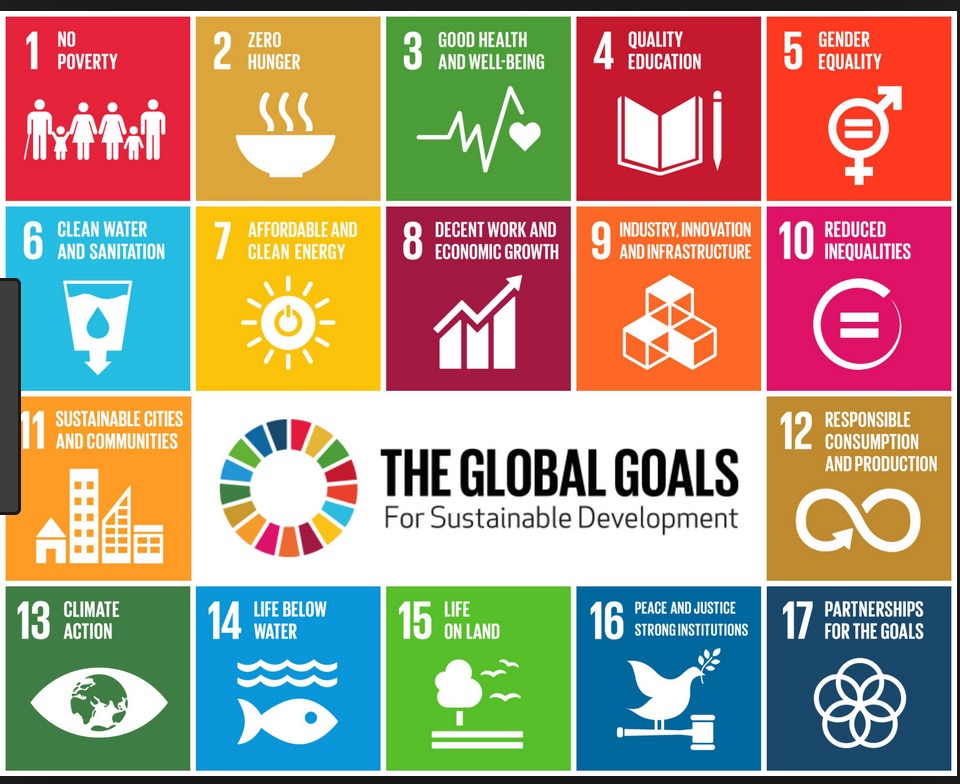

A few weeks ago in Brisbane I ran my first hypothetical. Its focus was the implementation of the United Nation’s 17 sustainability development goals. These goals, known as the SDGs, are for basic things like clean air and water, reducing hunger and poverty, increasing the quality of education, reducing gender inequalities and, in general, making life better for all Australians.

The results of the Senate Inquiry into the SDGs had just been released with a majority report (by Labor and the Greens) that said that the SDGs were important, we should be doing more, and recommended actions we could take. There was also a dissenting report (by the Liberal/National Coalition) that said, in effect, we were already doing everything and nothing would be served except more paperwork and anyway we don’t like the UN because it criticizes us unfairly (I’m not kidding about this last bit, this is what they said!) – and it concluded by saying ignore all the recommendations in the main report. So, there was not a lot of bi-partisan agreement there!

Well. who has the right of it?

Are we doing everything already or do we need to do more? According to a recent report by the Griffith Centre for Sustainable Enterprise, that looked at how the SDGs were being addressed (or not) in the policies of ten political parties.

“Australia’s ranking of 37 on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) dashboard indicates that for a developed country there are aspects of Australian society that need to be altered if it deserves to be placed in the top 20 OECD countries”.

Australia has signed up to achieve the UN goals by 2030, however if the minority report correctly reflects the view and intentions of the Liberal/National coalition, we will not be able to rely on Government. Australian progress will need to be driven by concerned individuals and groups – our growing CIVIL SOCIETY, of which Talking infrastructure, along with many professional associations and NGOs, is a part.

Where to start?

The first thing to understand is that most people are unaware of this thrust by the United Nations. Ask anyone! Few know what they are. Many think that they don’t apply to us, but are for developing countries only. This is likely because of the UN’s earlier millenial goals which did apply only to developing countries.

The second thing is that there are 17 of these goals, with 169 specific targets. This is far too much for most of us to get our head around. Fortunately we don’t have to. Pick one or two that you feel strongly about and work to improve those! (just be aware of the others and mindful that what you do might impact another goal.)

Talking Infrastructure is now working with participants in the Hypothetical – all of whom were sent as representatives of their associations – to discuss what next steps can be taken since all of 17 goals either impact, or are impacted by, the infrastructure decisions we make.

Add your ideas to the hypothetical

The set up is this

” Six months have passed and the new government urgently wishes to address the issue of implementing the SDGs. Moreover it has realised that it has major leverage that has so far been little discussed – its power of the purse!

The Federal Government funds national infrastructure projects and provides substantial support to State and Local Government projects. The best and brightest (YOU) have been gathered together to explore how to take advantage of this.

Write some rules for evaluating infrastructure proposals so that they support the SDGs and Australia’s wellbeing.

Footnote: Thanks to EAROPH Australia for their courage in letting me play with this idea for them at their AGM

I have long been interested in one particular aspect of the history of asset management. Why was it that agencies would so often progress to the stage of being the envy of all others in terms of their asset management – only to collapse and have to rediscover everything they previously knew? I suspected that there must be something inherently unstable about asset management – and there is! Here I explain what the problem is and how you can make sure it doesn’t happen to you.

You are going to come across a lot of definitions of asset management. Maybe you already have. All have validity. But the one that I favour at the moment has a focus not on what asset management does – but rather on what we get out of doing it!

I look at asset management as ‘a series of process and information improvements that enable organisations to see not only the likely consequences of the decisions taken today – but also of the actions not taken.’ You can argue with this definition, but bear with me, because you will see how it can help.

When armed with a knowledge of likely consequences you can make better decisions. You may not have enough money to do everything, but if you understand the consequences you can be reasonably confident that the things you are doing are at least of greater value to your organisation or community than the things you are not. Even more importantly, you can demonstrate this to others.

Asset management protects you. If you are a councillor, it protects you from pressure by lobbyists and those who would have you spend council resources in ways which you know are sub-optimal. If you are an administrator, it enables you weigh up different uses of your limited resources. If you are a manager responsible for assets, it enables you to know what to do that will best meet the service needs of the community.The key word is ‘consequences’.

When you can tell what is likely to happen next as a result of the actions you take today – and of your inactions – you are able to make better decisions and make them with confidence. And when you are able to demonstrate this to others and gain their confidence, life becomes much more enjoyable.

Driving in the Dark

Driving in the Dark

Without asset management, you are operating in the dark. It’s like driving at night with your headlights showing you just a few metres of the coming road. You are only able to see a little way ahead, and all of your decision making, whether on short or long term goals, is constrained by having such a limited view. So you have to move cautiously, never quite sure what those shadows mean, or what is coming next. And you can easily miss your turning and have to make time wasting course corrections. Or at worse, run into something with expensive, maybe fatal, results.

Introducing asset management is now like switching on your high beam.

Introducing asset management is now like switching on your high beam.

Suddenly, with a better view of the likely consequences of your actions, you can now see a long distance in front. You can move forward more confidently, make better decisions, and avoid potential problems, because you understand the likely consequences of actions and inaction.This is very exciting and it is not difficult to see why asset management creates evangelists. Many of you will have experienced this in the early stages of asset management, when, perhaps for the first time, you now have an overall view of your asset base, a better understanding of what you have, what condition it is in, and what its value is. This gives you a completely different view of what you can do – and it is pretty heady stuff.

But a word of caution!

What I have learnt is that when you reach this stage, you must not stop. The High Beam stage is unstable. When you are on the road, any approaching vehicle can force you to switch them off. Similarly when you are starting asset management, and you adopt generic assumptions about asset lives and desired service levels to get yourselves started, you get a ‘great leap forward’. This is the ‘switching on the high beams’ stage. It enables you to make progress quickly.

As in all things, easy come – easy go!

When things get tough – the asset management equivalent of the oncoming traffic – you can no longer rely on those generic assumptions and service levels. In times of trouble, such as missed grants, unexpected and unfunded asset renewals, in fact any difficulty, your staff and your ratepayers need to have full confidence in the reliability of your system and this means that you need to move on from the generic data and develop information that is credibly yours. In other words, you need to customise, to make the service levels and associated asset lives your own.

To do this you need to work with your community to develop service levels that are widely understood and accepted and can withstand criticisms.

Your asset data needs to reflect these service levels and to demonstrate the reliability that comes from documented, efficient, update mechanisms. Your asset lives need to reflect your own local conditions and known maintenance histories. And you need robust processes to ensure that all new asset acquisition reflects your strategic directions.

This takes effort, commitment – and time.

However, once you have done this, you are largely failure proof. By the time you have developed a good understanding throughout your staff from field staff to CEO, board or councillors, by the time you have good, up-to-date data, and by the time you have the confidence that this brings, then your asset management is secure.

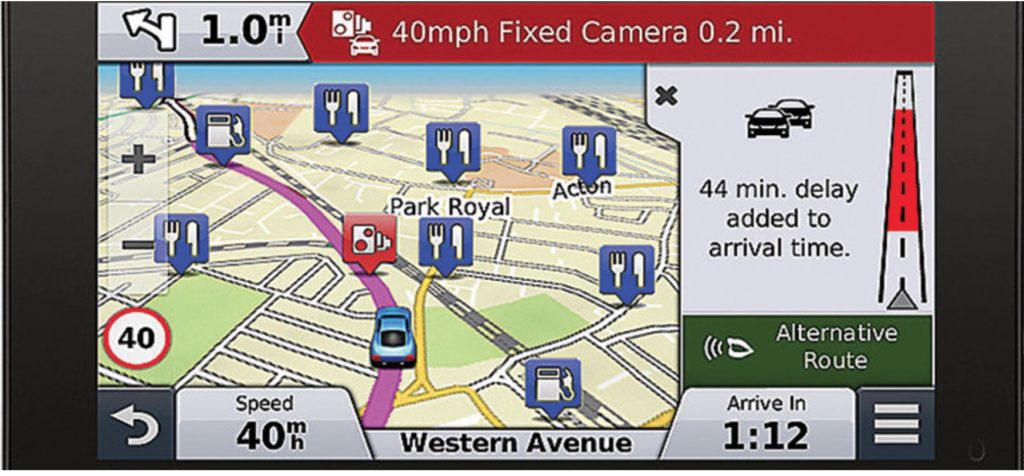

You have successfully navigated the instability phase and come out safely on the other side. This stage of asset management is like adopting a Satellite Navigation System. Now you can analyse all the options and choosing the optimum course is easy.

Moreover, when you get here you won’t want to stop. Now, asset management improvement for the benefit of your community will simply be the way you do business and you will enjoy always seeking to do better. The Road Ahead is now clearer and you travel it with confidence.

Questions?

- Where are you on the road to sound, reliable asset management?

- Are you still at the stage where you are using general purpose asset lives, gleaned from somewhere else? Or have you customised?

- Have you established accountable service levels? And are these service levels clearly and transparently connected to your asset life data? Do they inform your understanding of effective age and time to renewal?

- Have you reviewed, updated and streamlined your asset management practices?

Think this is too much work?

Then be sure to read next week’s post where we look at the danger not only for your assets, but for your staff ,of not getting to this stage of asset management.

Next Week: AM Protects – your staff!

Transparency of government is the greatest tool we have for ensuring the best decisions are made by officials and functionaries and reducing corruption and poor decision making.

Legislation, guidelines and reviews surrounding Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) abound as we collectively try to find a way for government to utilise private efficiency and expertise without exposing the public to risks associated with corruption of officials and contracts that serve the private rather than public partner.

The problem with many PPPs and government business, are poorly constructed contracts. Inappropriate measures, guarantees of returns and unclear maintenance and renewal responsibilities.

In the past it has been difficult for us to measure the use of infrastructure by different groups, the consumption / degradation of infrastructure, the degree of maintenance and renewal required and applied to infrastructure.

This has lead to simplistic drafting of contracts based on unsupported estimates.

Enter micro-transactions and Internet of Things.

We now have the unprecedented ability to measure almost everything, and cheaply. We have technology that allows us to make the recording of these measurements publicly available and immutable, and we have people writing clever contracts based on micro-transactions.

By combining these things there is opportunity for us to include all aspects of infrastructure in government contracts for PPPs. Reward can flow to the Private Partner based on utilisation, maintenance, renewal of the infrastructure as well as other measurable impacts, such as improvement of performance of the infrastructure, or lessening of burdens on society and the environment.

In the last post I took up Eli Goldratt’s contention that most of us are focussed on efficiency (doing what we are currently doing but doing it better) because that is what we feel we have most control over. I asked what was missing. But another way of looking at this problem is not at what is missing – but at what should be! Policies or practices that we have hung onto that are no longer serving us well in the new environment we are trying to instigate. Let’s again turn to Goldratt who argues that

In the last post I took up Eli Goldratt’s contention that most of us are focussed on efficiency (doing what we are currently doing but doing it better) because that is what we feel we have most control over. I asked what was missing. But another way of looking at this problem is not at what is missing – but at what should be! Policies or practices that we have hung onto that are no longer serving us well in the new environment we are trying to instigate. Let’s again turn to Goldratt who argues that

“Technology can be beneficial if, and only if, it diminishes a limitation.”

This may be a limitation that we are so used to we take it as the way that life is. For example 200 years ago, travel was so slow that it was not feasible to work a full day AND also travel ten miles. This meant that if you got a job in another town you moved to that town. Today many travel much further. Workers 200 years ago would likely not have seen travel time as a constraint, it was ‘just the way that life is’. The iPhone and the Ipad were great innovations but many of us were not consciously aware of the limitations they diminished – until we got them!

The importance of limitations is that humans are intelligent. When we have a limitation we develop work arounds, rules that help us manage. But if we do not change the rules (e.g. our work practices, our policies, our regulations) we cannot get the full benefits of the innovation.

Which leads him to ask 4 questions that might be useful for you.

- What is the power of the new technology or innovation?

- What limitation does it help alleviate?

- What is the cost of the work around rule for that limitation?

- What is the new rule? and its cost?

These questions are not easily answered, especially the last one, but the more I look at them, the more critical they seem to be.

Thoughts?

The reason why we focus on efficiency is because we can. Doing what we are currently doing – only doing it better, cheaper, faster – is not only within our capabilities it is also within our responsibility levels. Effectiveness requires going beyond, looking at how what we are doing interrelates with what others are doing. Doing our thing better will fail to achieve real benefits unless we do. So while efficiency is desirable, it is not enough. Here is a case in point.

The reason why we focus on efficiency is because we can. Doing what we are currently doing – only doing it better, cheaper, faster – is not only within our capabilities it is also within our responsibility levels. Effectiveness requires going beyond, looking at how what we are doing interrelates with what others are doing. Doing our thing better will fail to achieve real benefits unless we do. So while efficiency is desirable, it is not enough. Here is a case in point.

The asset management team proposed that the government build an asset register that would provide information to enable the transfer of property from departments that no longer had need for the resources to those that did. This, they argued, would enable great savings in both capital and maintenance funds. So the asset register was built. It took a number of years and cost many millions of dollars and when completed it did exactly what it was intended to do – it showed where property was underutilised and where capacity was under strain.

The expected benefits, however – the transfer of surplus property saving both capital and maintenance funds – did not arise. Why not? Because information by itself is not enough. We also need people and processes that want to and can make use of the information.

In this case no department with surplus property was willing to admit it and hand it back to the Treasury. It knew that if their demands should increase in future, getting expansionary funds would be very difficult, so there was an incentive to disguise and minimise the true extent of under-utilisation.

There was no organisational mechanism. Departments needing to expand would make the case to their Minister, usually done by proposing a specially designed facility. On approval, these departments had no incentive to settle for hand-me-down space and there was no organisational means to make it happen.

QUESTION: What project benefits have failed to materialise not because of what you did, but because of what others didn’t?

“We can’t let politicians make decisions, they are so irresponsible!” This was the reaction by a group of academics to the suggestion that politicians should be free to allocate their own weights to various criteria (cf last post on multiple criteria decision making)

“We can’t let politicians make decisions, they are so irresponsible!” This was the reaction by a group of academics to the suggestion that politicians should be free to allocate their own weights to various criteria (cf last post on multiple criteria decision making)

I was first introduced to multiple criteria analysis when a UK researcher presented his work on the third Heathrow runway to a university staff seminar. The presentation was enlightening – and so was the reaction of those present. The senior public servants, who needed to get elected members focussed on the issues, were enthusiastic about the potential to present clear information not artificially constrained by dollar equivalents. But the academics were truly horrified when the presenter argued that elected members should allocate their own weights. As the people’s representatives – it was their objectives that were key.

In the last post, I asked who should be deciding on the weights. This is not a trick question but it is a difficult one. It bedevils serious public servants everywhere, staffers who desire to produce good quality ‘finished staff work’, to be able to anticipate all the problems, all the issues, all the questions, that decision makers could ask, and ensure that they have been addressed.

But this can then slip into believing that, having done all the analysis, the staffer now knows best what option should be selected and so we get the three card trick – presenting the decision makers with only three options, two of which are obviously out of consideration for cost or other reasons, so that effectively the decision makers are forced to choose what the staffer has determined.

Multiple criteria analysis, presented honestly without weights, allows decision makers to seriously and knowledgeably to consider the issue. The final decision may not be so predictable but it is likely to have their greater long term support.

On 9 September I wrote a post “Are Politician the real decision makers?” which attracted more comment than most other posts and the commentary was good. Have a look.

Also see Kim Geedrick’s comment on the last post

QUESTION TODAY IS GENERAL – YOUR THOUGHTS?

Recent Comments