As a board member of several boards I learnt to be suspicious of a ‘one-off’ reason/excuse for failure. Especially if the same problem returned but was ‘explained away’ with a different ‘one-off’ answer. It was always worth drilling down for the root causes, always worth examining the process.

As a board member of several boards I learnt to be suspicious of a ‘one-off’ reason/excuse for failure. Especially if the same problem returned but was ‘explained away’ with a different ‘one-off’ answer. It was always worth drilling down for the root causes, always worth examining the process.

A poor outcome can be used as an opportunity to improve a process. You will find that the trust in you and your processes will increase if you do, as illustrated in the following two stories:

1. The Quality Control Manager of a large white goods industry tells how sales considerably increased when he took the trouble to explain to sales staff what problems had occurred in the past and what had been done to ensure that they would not happen again. The sales staff used these stories in their conversations with potential buyers who were impressed by the quality improvement processes involved. They bought into the process – and the product. But even more interesting, he told me that if customers had had an initial problem with a product butit was fixed promptly and courteously, they became more loyal customers than those who had not had a problem at all! The reason is that with their good experience of correction, they now trust the process.

2. This is a personal story: I was working on a report, one of a series, for the South Australian Public Accounts Committee, and discovered a flaw in the modelling – at the 11th hour! The Committee had approved it and the House had been advised we would be tabling but when we sat down to write the press release it became evident something was wrong. Worse, I had no idea how to put it right.This presented somewhat of a problem as the rules are that once the Committee commences an investigation, it must publish its findings. Nobody had noticed, and perhaps nobody would, but I knew it was there. We could not let it go ahead and had to advise the House that there would be a delay. In the event I was able, after much further and anxious work, to find the solution. But I was convinced that after this embarrassing hiccup the Committee would never trust my judgement again and I was prepared for a hard time when I presented the next report in the series. It never came. In fact, they were less, not more critical and searching. I was very puzzled. The Committee Secretary grinned: “Why should you be surprised? They now know that the process can be trusted, for when the going gets tough you will protect them from embarrassment at the cost of your own”. That poor outcome had, paradoxically given me an advantage! With the chance to refine and demonstrate the strength of our checking procedures, trust levels went up!

Question: Could this be an answer to our decision-maker’s dilemma’s (Oct 21 and Oct 25)?

It happens a lot! A senior staff member visits another country, sees something new, comes back full of enthusiasm to have the system installed here. His idea is new and exciting and it is given consideration. Time passes, the protagonist commits all his energies to getting the new project accepted and he is successful. In the meantime, over in the original country, experience with the new system is already throwing up a great many problems. Already the original country is starting to regret adopting the idea and is making excuses for the problems that have already arisen. The protagonist and his team, of course, hear about these problems.

It happens a lot! A senior staff member visits another country, sees something new, comes back full of enthusiasm to have the system installed here. His idea is new and exciting and it is given consideration. Time passes, the protagonist commits all his energies to getting the new project accepted and he is successful. In the meantime, over in the original country, experience with the new system is already throwing up a great many problems. Already the original country is starting to regret adopting the idea and is making excuses for the problems that have already arisen. The protagonist and his team, of course, hear about these problems.

Now they have a decision to make. Do they bring these problems to the attention of their superiors? If they do so, their position on the most innovative departmental project team, which is bringing them lots of interest and kudos, is at risk. Besides the directors, department chiefs and even the Minister have already made favourable noises about the project. Not so much that it could not be quietly shelved, but still it could be a bit of an embarrassment. Do they risk embarrassing their seniors or go ahead with the project despite the serious objections now being raised overseas?

This problem is not confined to the public sector, and is certainly not avoided by contracting out the work to the private sector.

Questions:

- What are the arguments in favour of change in these circumstances?

- What are the arguments in favour of doing nothing?

- Would a change in the system help? If so, what?

In his October 11 post, Gregory introduced the trolly problem and asked whether it is ethical to not take action when by doing so you could save a life. It is a tricky problem, a real ethical dilemma which is why the trolly problem has lasted so long in the literature. It might seem that as advisors on asset decisions we are never in such a dire life-or-death decision, yet is this really so? Consider the Railway Signalling Project.

In his October 11 post, Gregory introduced the trolly problem and asked whether it is ethical to not take action when by doing so you could save a life. It is a tricky problem, a real ethical dilemma which is why the trolly problem has lasted so long in the literature. It might seem that as advisors on asset decisions we are never in such a dire life-or-death decision, yet is this really so? Consider the Railway Signalling Project.

The signalling system was part of a larger redevelopment of the railway station and had taken many years to design and develop and to pass all the various hurdles that such large scale public developments require. It had also languished a long while with the cabinet sub-committee entrusted with making such decisions. Now, during this time it had become perfectly obvious to all the departmental protagonists that there was a far better signalling system now available, one that would be cheaper, easier to install and maintain and far more reliable. The question was: Do we issue an amendment to the original design to take account of this new development which would invitably slow the already lengthy procedure even more, but would save considerable money and, quite possibly, lives because of the greater reliability of the new system?. The ease of installation of the new system would allow us to recoup some of the extra planning time involved. Or, now that we are so close to the finish line and have spent so very much time in deliberation already, do we simply run with the inferior system and say nothing?

The organisation chose the latter course of action and the railways thus ended up with a more costly and worse performing system than it could have had.

Question: Were they right to have done so? What would you have done?

“When the first attempts at systematic weather forecasting were made, one idea was to look back through the records for a day where the weather was much the same as the day when the forecast was being made. The assumption was that the weather on the following day would be the same as the weather on the following day in the historical past. But surprising events are always occurring to disrupt this sort of forecasting.” (from Len Fisher’s talk on the ABC’s Okham’s Razor, 11 May 2016.

“When the first attempts at systematic weather forecasting were made, one idea was to look back through the records for a day where the weather was much the same as the day when the forecast was being made. The assumption was that the weather on the following day would be the same as the weather on the following day in the historical past. But surprising events are always occurring to disrupt this sort of forecasting.” (from Len Fisher’s talk on the ABC’s Okham’s Razor, 11 May 2016.

We laugh now at the absurdity of these first weather forecasters. However, many in the stock market still analyse charts of past stock prices to predict future changes (this is a bit more complicated, perhaps, but it still seeks to find answers to the future from the past) At least, if you get it wrong with stock prices, you lose a bit of money but can try again tomorrow. But if you apply these ‘looking back’ ideas to future infrastructure investment decisions that will impact our communities for decades, that is a very different matter.

Thirty years ago when I became interested in infrastructure planning, it was common to take a rising trend and simply extrapolate it and although it often resulted in major oversupply, we still did it. And we are still doing it! We just use more complicated algorithms.

But if not extrapolation of the past, what techniques are available for anticipating a changing future?

Here is a story about looking forward that you might enjoy.

Here is a story about looking forward that you might enjoy.

Many farmers use windmills to run bores for stock watering but pumps allow water to be extracted from much deeper resources. It is critical, however, that the pumps work or the stock dies. A friend had set up a business in selling – and servicing – pumps to farmers and his business was flourishing. He would routinely drive out and check all the pumps to ensure that they were working well.

Then he had the idea of buying a drone to do his survey work for him, but not a $500 hobbyist model, he decided on a top of the line model from the leading drone producers in Israel. He sent off his $27,000 cheque – only to have it returned to him! The Israeli government said it was not prepared to sell it to him for security reasons!

This was about 8 months ago. Not to worry, he said, soon there will be satellites I can connect to and I will be able to check the pumps using my smart phone!

This is a fellow who is keeping his eye on the rapid rate of technology change.

No specific question today – just enjoy!

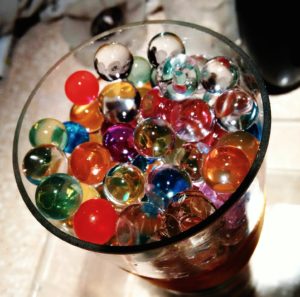

“General equilibrium”, an economics colleague explained, “is like a bowl of marbles, move one and we have to reckon with a change in every other one. Depending on the location of the original marble, the change will be large or small, but there will be always be a change.”

“General equilibrium”, an economics colleague explained, “is like a bowl of marbles, move one and we have to reckon with a change in every other one. Depending on the location of the original marble, the change will be large or small, but there will be always be a change.”

Thinking now of energy, a breakthrough in battery storage development would be the equivalent of moving a marble at the very bottom of the bowl. Anyone following the technical developments in batteries, and the vast resources now being devoted to this exercise, would expect to see this happening within the next five years (and probably sooner rather than later). In other words a breakthrough in the length of life and the economics of solar energy (and wind energy) storage is an almost certainty. But what then?

As important as technological innovations are, they are not the end of the story. In fact they are just the beginning. When battery storage possibilities improve, here are some of the impacts we can expect to see – a change in social attitudes towards energy usage; changes in manufacturing to take advantage of this; a great increase in the demand for solar panels; an increase in the willingness of some to go completely off grid; but also an interest of many more in adapting the present distribution network to serve localised production and sharing of power. Localised power production and distribution will enable greater security from events such as the recent power outage in South Australia and future impacts from climate change, as well as attacks on our critical infrastructure.

However, the change in demand for distribution networks will present a business model challenge for network owners which is why ‘economic innovation’ is now needed. No change will take place unless a profit can be made from it. Profit is not a dirty word. It is essential to good resource allocation.

So my question today is: what do we know of research into new business models that can promote and support the adaptation to distributed production and distribution that solar and wind power combined with good battery storage can make possible?

By now, every Australian would know that the entire state of South Australia experienced a power system failure as severe storms with high winds uprooted 22 high voltage power pylons cutting off a major part of system generation at Port Augusta. For about 10 hours on Wednesday, we all effectively went ‘off grid’. Rolling blackouts or brownouts are not uncommon but this was the first time that an entire state has been without power.

By now, every Australian would know that the entire state of South Australia experienced a power system failure as severe storms with high winds uprooted 22 high voltage power pylons cutting off a major part of system generation at Port Augusta. For about 10 hours on Wednesday, we all effectively went ‘off grid’. Rolling blackouts or brownouts are not uncommon but this was the first time that an entire state has been without power.

At 3.30pm light and power was cut to my office. The desk top computer stopped – the laptop, however, continued working for another 5 hours. The land line phone connection ceased – but the mobile did just fine. Televisions stopped but information got out to everyone via Facebook on mobile connections. Power was mostly resumed at 1.10 am Thursday but, for ten hours, the battery was king!

Those in government responsible for the future of our infrastructure might well have asked themselves whether climate change might not engender future storms like this and, reflecting on the fact that the statewide blackout was caused by the necessity to protect the integrated system, perhaps they might also have asked themselves whether the efficiency benefits of integration might not come at a cost? They might then have considered whether a more disintegrated system of power generation and distribution, such as is now available with the growth of renewables such as wind and solar might not have mitigated the impact? After all, when the system goes down, those who are not reliant on it benefit. So it is curious that the Prime Minister and assortment of others antagonistic to wind and solar should blame renewables for the failure!

Or perhaps not so curious if the aim is to protect incumbent power and distribution networks? The electricity industry is well aware of the threat of wind and solar to its generation and distribution networks when long lasting batteries are developed, which is now, perhaps, not more than five years away.

Our Question today: Given that battery development will represent a major disruption to power production and distribution what should be the intelligent, forward looking, attitudes of our government – to block, or to adapt?

Recently at a workshop of asset managers I suggested that the role of Strategic Asset Managers in today’s environment will be to anticipate the changes that are affecting their organisations policies and be ready to address them. I asked them to come along prepared to discuss the key trends affecting their organisation and what they were planning to do about it.

Recently at a workshop of asset managers I suggested that the role of Strategic Asset Managers in today’s environment will be to anticipate the changes that are affecting their organisations policies and be ready to address them. I asked them to come along prepared to discuss the key trends affecting their organisation and what they were planning to do about it.

The key trend identified was diminishing or uncertain funding. No surprises there.

What I found interesting, however, was the way that almost all of them were coping with this situation. It was to place a greater focus on the ‘customer experience’ and to broaden the scope of their activities. A university asset manager said that they were seeking to provide staff, students and researchers with ‘desirable experiences’. The airport manager was looking to extend the airport facilities to attract not only passengers and those who came to greet or see them off, but people who would come to the airport for the events or activities it provided, rather than for the intention of flying. The asset manager from the electricity authority said that they now saw themselves, not in the electricity business but in the energy business. He too, saw the need to focus on customer experience. In fact, he recognised that in this new environment that ‘asset management’ and ‘marketing’ had to come a lot closer, for they had a common goal.

Infrastructure management and marketing! An interesting combination.

So my question for today is: Is this the way you see infrastructure moving?

I am often told that I should be targetting ‘Talking Infrastructure’ at the politicians because they are the real decision makers. But are they?

I am often told that I should be targetting ‘Talking Infrastructure’ at the politicians because they are the real decision makers. But are they?

Politicians are like a jury. The lawyers make their best case and the jury chooses between them. The result depends on the skill of the lawyers who have to examine the facts before them, assess their validity, make a case and then present it as persuasively as they can. Now the lawyers may not have all the facts, or the jury may be influenced by matters other than the facts – the look of the defendant, perhaps. It may be that the guilty go free, or the innocent are convicted. No reasonable person could think that this is ‘fair’ or ‘right’, but it is the way we discover the truth under the legal system we have. Importantly the jury is chosen deliberately for its representativeness, not analytical skills. To get better results from our jury system we therefore work on improving the system – and the quality of the lawyers who analyse and present the information.

Politicians are like a jury. Infrastructure analysts examine the issues, collect data, analyse it, make a case and present it. They are like the lawyers. The politicians then have to take a stand. The analysts MAKE the case. The politicians TAKE a stand. That is why I refer to the analysts as ‘infrastructure decision MAKERS’ and the politicians as ‘infrastructure decision TAKERS’. Semantics perhaps, but a useful distinction.

It is also why I am targetting this Talking Infrastructure Blog at the analysts and not at the politicians. It is the analysts who can make a difference.

Whether a proposal ‘gets up’ depends on

- the merits of the proposal itself,

- the skill with which it is presented, and

- the match between it and the needs of the politicians

All of these (yes, even the last) are within the capacity of the analyst – the infrastructure decision maker – to improve. End of manifesto!

Question for today: Do you believe we need to better understand the needs of politicians. Why or why not?

In his post on August 12, Mark Neasbey of the ACVM spoke about the infrastructure decisions we make when we don’t think we are making any. Dangerous! If you haven’t read it yet, it’s worth it! Click here. And here is another example of unconscious decision making.

In his post on August 12, Mark Neasbey of the ACVM spoke about the infrastructure decisions we make when we don’t think we are making any. Dangerous! If you haven’t read it yet, it’s worth it! Click here. And here is another example of unconscious decision making.

At his last school, surplus capacity was up around 45-50% and the school principal approved the use of one of the vacant classrooms as a drop in centre for parents and carers.

Now he was also on the council for another school, one his own children attended. This school was in a growth area and had no surplus capacity, but when he spoke of his drop-in centre, the other council members thought it a good idea and since school extensions were being designed at the time, the second school agitated to have a drop in centre designed into the new building.

The designer liked the idea and in the next school design he was involved in, he automatically included a drop in centre.

Now what had begun as a good use of surplus capacity, a “one off”, had become a new standard. Who approved the ‘new standard’? In all likelihood, no-one. When was a conscious decision on the new standard taken? In all likelihood, never. Was the corporate level (in this case the Education Department) even aware of the change? In all likelihood, not at all!

This is infrastructure or service level creep. Everyone defends it. Why wouldn’t they? A better service at no cost is what we should all aim at. But what is ‘no cost’ when we already have surplus infrastructure, becomes very costly indeed when the extra space is being deliberately built in.

This is not to argue against drop-in centres, per se. They can be a great addition to a school and to the community. But rather to suggest that the decisions be taken advisedly. To do this we must first be aware of it!

Question: What examples of infrastructure creep (or service level creep) can you think of?

Recent Comments