In the late 1950s, peaking in the mid 1960s, there was a great need for infrastructure as our population was growing rapidly. This was a time of full employment. We are again looking to infrastructure to get us out of the downturn that Covid has caused. But is it the ‘right’ solution now?

A little bit of history, 1950 – 1985

With its large land mass and tiny population, Australia had long feared invasion from their crowded northern neighbour, Indonesia. So, after the war it took advantage of the opportunity to build its population by encouraging both refugees and migrants. In addition to the overseas influx, the 1950s also saw the beginnings of the baby boom. Australia’s population rose extremely rapidly in a very short space of time and quickly outstripped growth in housing. At the time, two and even three families might have to share a house.

The private sector could not move fast enough so the Commonwealth took up the challenge.At the time, it was flush with funds for with women now entering the workforce in large numbers, tax revenues were greatly increasing, and with the need for social welfare very low, it could afford to spend – and it did. It created large rental housing estates, hundreds of new suburbs, all with supporting infrastructure in water, electricity, roads, etc. And so, for over 30 years, an entire generation, we experienced rapid construction growth, we didn’t know anything else.

More history, 1985 –

But by 1985, things were changing. Population growth was slowing. The Federal Government was no longer flush with funds. It was time for construction to slow down. The large expansion of infrastructure in the past thirty and more years was also presenting demands of its own. Logically we needed to consider switching our attention from growth to maintenance and over the next ten years this was to become even clearer.

But there was resistance, and it came from three sectors – industry, where the large construction companies built up during the building boom did not wish to see demand for their services reduced; politicians, who saw growth in State GDP and constant infrastructure announcements as proof of their ability to serve the people; and the construction professionals themselves, whose numbers greatly exceeded the fledgling asset management professionals.

With the change in history, came a change in justification for construction

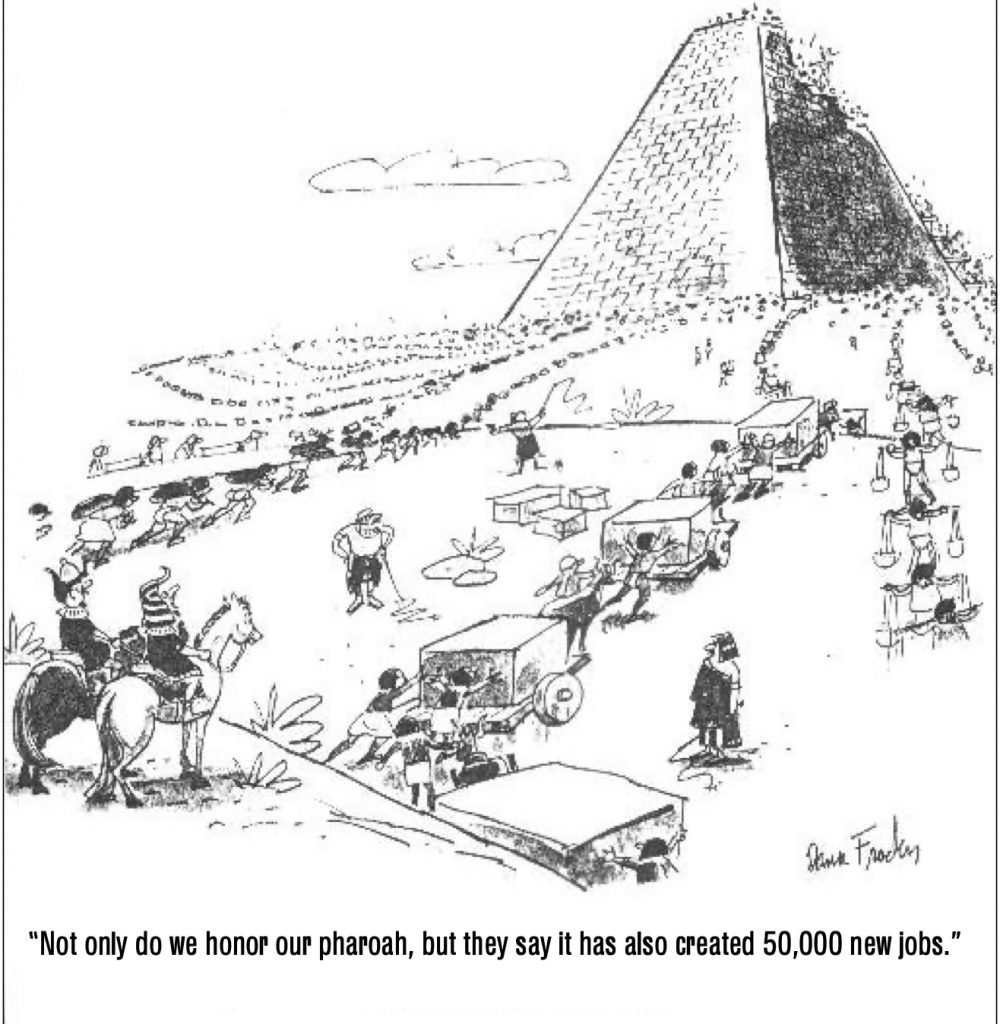

With population increase slowing, and so much infrastructure now completed, we could no longer justify major construction by reference to urgent need – so we changed the justification. It was now argued that infrastructure ‘created’ employment. Many still believe that this is so. But actually, it is public spending that creates jobs – no matter where it is spent, on infrastructure – or on services.

We are also now rethinking ‘the goal’ for infrastructure.

What do you think the goal for infrastructure should now be?

The goal of infrastructure is to serve the people. “Serve” means to provide the best service. The definition of “best” includes every conceivable measure, including affordability, longevity, maintainability, foregone opportunity, impacts on environment, future generations, amenity and culture. These measures require rigorous testing, and should be in place from the point of conception, so alternative designs and means of service provision are continually tested.

We don’t often make smart infrastructure decisions, we tend to quickly solve problems. The advance of technology has not helped us very much here. If we are designing a little piece of infrastructure, like a chip, or circuit board for a computer, then many millions of different designs will be tested, with the optimal being selected for production. For a far less technically complicated public infrastructure, like a stadia, far fewer designs are modelled, and the measures that matter the most over time, are poorly included.

I’m optimistic that as a species we will get better at making the best decisions.

The role of infrastructure is to provide for civil society, in environmental, economic and social functioning.

There are a number of implied commitments in this sentence, such as being a civil society implies a level of responsibility and good practice.

We must remember we are a civilisation not an economy.

Building something because it creates jobs ignores the long term costs of lifecycle management, but does get politicians into high vis vests and hardhats.

Thanks Gregory and Ashley. It is curious, but sad, that whilst asset managers almost always think that the goal of infrastructure is to serve the community, few others do. How do we change a self serving mindset to a community interest mindset? Perhaps more generally speaking of ‘community’ rather than ‘economy’ might help? Other ideas?