For senior decision makers, infrastructure used to be a relatively simple matter – assign different teams of engineering and finance specialists to determine if it could be built and could be afforded. Infrastructure decision making is no longer simple, more a matter of juggling many factors, each of unknown severity and immediacy. This is why I have introduced the ‘big picture’ issues now being dealt with by the world’s financial elite at the World Economics Forum, and the many practical issues essential for economic, social and environmental sustainability, that the United Nations are grappling with in the 17 SDGs, the sustainable development goals.

For senior decision makers, infrastructure used to be a relatively simple matter – assign different teams of engineering and finance specialists to determine if it could be built and could be afforded. Infrastructure decision making is no longer simple, more a matter of juggling many factors, each of unknown severity and immediacy. This is why I have introduced the ‘big picture’ issues now being dealt with by the world’s financial elite at the World Economics Forum, and the many practical issues essential for economic, social and environmental sustainability, that the United Nations are grappling with in the 17 SDGs, the sustainable development goals.

Being aware of the issues is clearly the first step, but then what?

How would you go about including these goals in your own infrastructure decision making? And how would you know when you have been successful? The Australian Senate has recently launched an inquiry into the implementation of the SDGs. Here is what they are looking at. (Note that the last 4 line items refer to Australia’s work in supporting other nations.)

Questions for Today:

- Are they the right questions for the Senate? What is missing?

- Are they the right questions for You in your own infrastructure decision making? What questions would you add, or modify?

Here is the Senate Inquiry’s Terms of Reference

An inquiry into:

- the understanding and awareness of the SDG across the Australian Government and in the wider Australian community;

- the potential costs, benefits and opportunities for Australia in the domestic implementation of the SDG;

- what governance structures and accountability measures are required at the national, state and local levels of government to ensure an integrated approach to implementing the SDG that is both meaningful and achieves real outcomes;

- how can performance against the SDG be monitored and communicated in a way that engages government, businesses and the public, and allows effective review of Australia’s performance by civil society;

- what SDG are currently being addressed by Australia’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) program;

- which of the SDG is Australia best suited to achieving through our ODA program, and should Australia’s ODA be consolidated to focus on achieving core SDG;

- how countries in the Indo-Pacific are responding to implementing the SDG, and which of the SDG have been prioritised by countries receiving Australia’s ODA, and how these priorities could be incorporated into Australia’s ODA program; and

- examples of best practice in how other countries are implementing the SDG from which Australia could learn.

Our January theme is ‘Getting Ready for Change’. One of the biggest changes is that infrastructure is no longer a national, but a global game.

Our January theme is ‘Getting Ready for Change’. One of the biggest changes is that infrastructure is no longer a national, but a global game.

In the last several posts we briefly looked at the issues being addressed at the World Economic Forum. But WEF is not Australia’s only major international commitment impacting our infrastructure decisions.

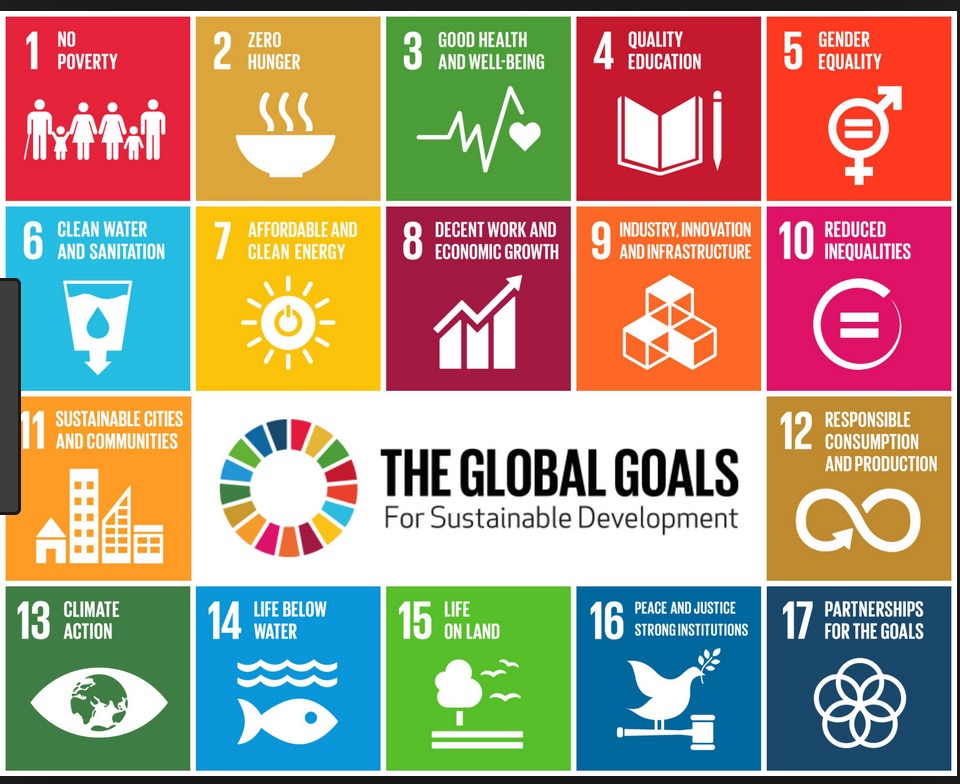

The Australian Government is also a signatory, along with over 190 other countries, to the United Nations 17 sustainable development goals, or SDGs. This requires the co-operation of all levels of government, all business and really all individual Australians. Yet how many of us are even aware of these goals?

The Senate has recently opened an inquiry into the implementation of the SDGs and we will look at this next few posts. But first, consider the goals themselves. Unlike the United Nations’ earlier Millenial Goals which focussed on developing countries, the SDGs apply to all, developing and developed alike.

One of the first steps is getting ready for change is to be aware of the global game we are now playing in.

So Three questions today:

- On an individual level: how many of the goals apply to consumption choices you make?

- On an organisational level: how many of the goals apply to the work your organisation does?

- On a government level: how many of the goals apply to the decisions our governments make (at all levels)?

If you would like to share your thoughts on these issues, please do – just click in the menu above the item ‘leave a comment’.

‘Experts’ have been taken to task for being ‘close focussed’, thinking only of their own area and not connecting with the wider world. If infrastructure decisions are to improve our world, they need to take in the wider context. How difficult this will be is, I think, indicated in the following statement of purpose for the World Economic Forum that begins this week in Davos.

‘Experts’ have been taken to task for being ‘close focussed’, thinking only of their own area and not connecting with the wider world. If infrastructure decisions are to improve our world, they need to take in the wider context. How difficult this will be is, I think, indicated in the following statement of purpose for the World Economic Forum that begins this week in Davos.

Creating a Shared Future in a Fractured World

“The global context has changed dramatically: geostrategic fissures have re-emerged on multiple fronts with wide-ranging political, economic and social consequences. Realpolitik is no longer just a relic of the Cold War. Economic prosperity and social cohesion are not one and the same. The global commons cannot protect or heal itself.

Politically, new and divisive narratives are transforming governance. Economically, policies are being formulated to preserve the benefits of global integration while limiting shared obligations such as sustainable development, inclusive growth and managing the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Socially, citizens yearn for responsive leadership; yet, a collective purpose remains elusive despite ever-expanding social networks. All the while, the social contract between states and their citizens continues to erode.

The 48th World Economic Forum Annual Meeting therefore aims to rededicate leaders from all walks of life to developing a shared narrative to improve the state of the world. The programme, initiatives and projects of the meeting are focused on Creating a Shared Future in a Fractured World. By coming together at the start of the year, we can shape the future by joining this unparalleled global effort in co-design, co-creation and collaboration. The programme’s depth and breadth make it a true summit of summits.”

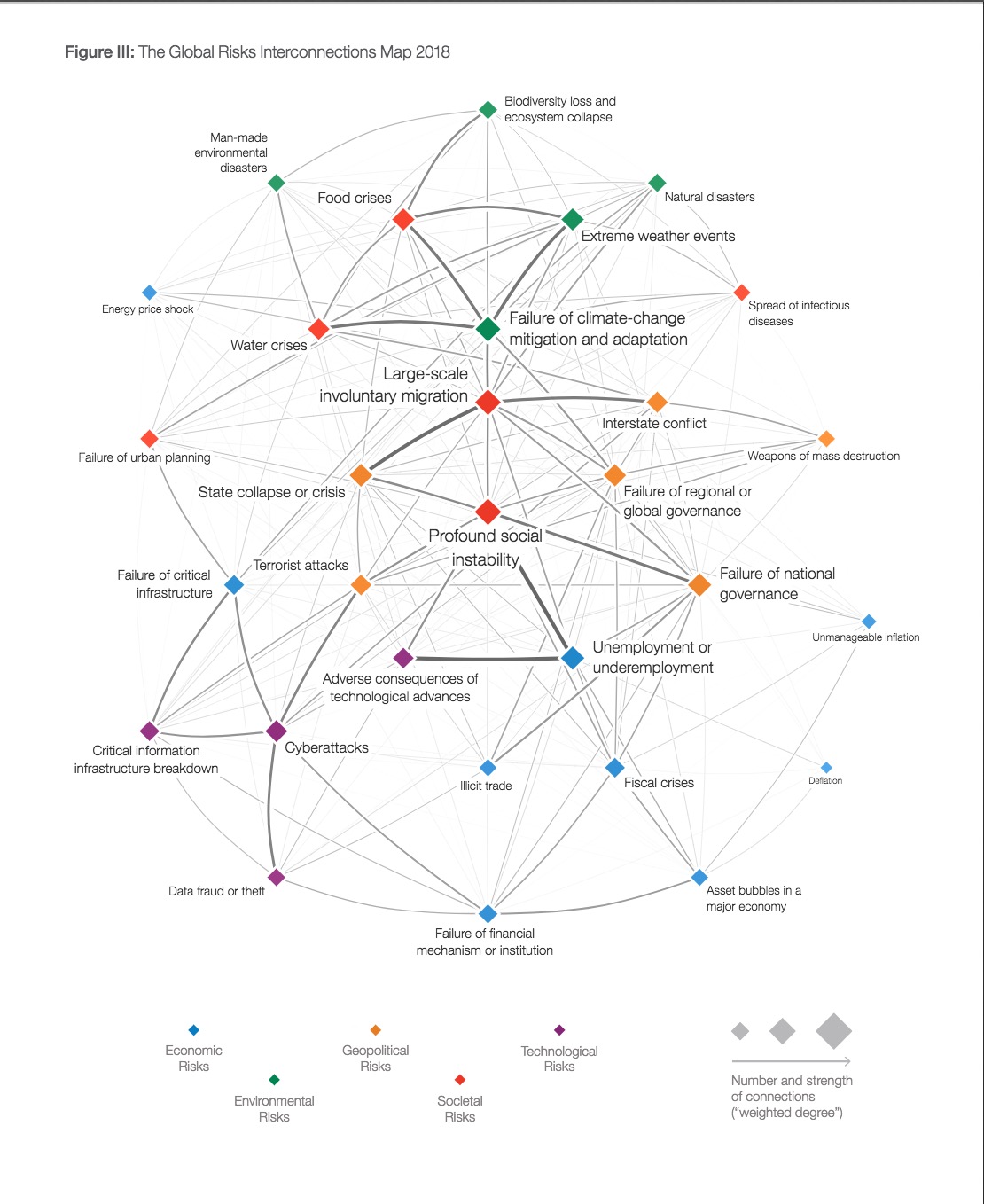

Next week Australia will join world leaders, big business and international institutions at the World Economic Forum in Davos. Ahead of this meeting WEF has released its Insight Report “The Global Risks Report 2018”. It is worth reading – and fascinating! This is the world for which we need to make future infrastructure decisions. Here is a glimpse.

Next week Australia will join world leaders, big business and international institutions at the World Economic Forum in Davos. Ahead of this meeting WEF has released its Insight Report “The Global Risks Report 2018”. It is worth reading – and fascinating! This is the world for which we need to make future infrastructure decisions. Here is a glimpse.

Also of interest for future planning is the section of the report that contains a chart showing how the risk profiles have changed year on year.

Thoughts?

Penny: We talk a lot about change today but as Chris Adam, Director of Strategic AM Pty Ltd, Brisbane, Qeensland, points out in this post, change has always been with us – and we have survived. But consider our reactions to the changes that have occurred within the last 100 years. Have we really done much better than just blunder through? And, can we do better now? Indeed, “how” do we ‘rethink the future’.

Do we just fight fires?

1. The Inevitability of Change

We need only reflect on the last century to recognise the inevitability of change:

- The second decade of the 20th century was defined by “the war to end all wars” which brought destruction and dislocation on a scale never before experienced

- The 1920s were a decade of social and economic change finishing with the most disruptive stock market crash of all time;

- The 1930s yielded the depression with further social and economic dislocation on a grand scale;

- The 1940s was defined by WWII with death, destruction and dislocation on a scale that dwarfed our previous efforts;

- The 1950s were a massive social and economic challenge as the world rebuilt and millions immigrated;

- The 1960s sexual revolution;

- The 1970s energy crises;

- The 1980s “greed is good” decade;

- The 1990s with the “dot com bubble”

My point is not to undermine the idea that current forces are not indeed a major challenge but to demonstrate that change is inevitable and, as a species, we have a proven capability to respond to such challenges

2. How do we “Re Think” the Future?

We tend to see change as a threat and prefer it didn’t occur, so how do we address this challenge and avoid a “head in the sand” attitude?

We need to take the future seriously but predicting the future is problematic. With the possible exception of WWII, practically no-one forecast the massive changes that characterised each decade of the 20th century. Current predictions that IT will lead to massive unemployment as machines take over reflect the exact same claims in the 1990s where it was forecast that traditional retail was “dead” as people would abandon shopping (as an inefficient and limited way to produce what we want and need).

3. So, if we can’t predict the future, how do we “take the future seriously”?

Ideas?

Penny: Today’s post is by Hein Aucamp, Director, WA Integrated Asset Management, and member of our Perth City Chapter, WA, He considers what infrastructure decision making today might gain from what he has learnt from years in the volatile area of Information Technology.

I spent many years developing Engineering and mapping related software. Rapid change, which is becoming apparent in infrastructure, has always been a feature of Information Technology, where the knowledge half-life is said to be 2 years. I trust that Infrastructure Decision Making will never become as volatile as that but it will certainly be less stable than it has been in the past.

I spent many years developing Engineering and mapping related software. Rapid change, which is becoming apparent in infrastructure, has always been a feature of Information Technology, where the knowledge half-life is said to be 2 years. I trust that Infrastructure Decision Making will never become as volatile as that but it will certainly be less stable than it has been in the past.

Here are my suggestions of translatable lessons. One can cope much more easily with a volatile discipline by dividing it into two broad categories: first, timeless principles; second, current methods to achieve the timeless principles. We need to be able to distinguish between them, to hold tightly onto the timeless principles, and also to be lightly invested in what is temporarily useful.

Timeless Principles

To get our thinking started, I suggest that these are some of the timeless principles:

• Infrastructure must solve a human need. This sounds as if it is stating the obvious, but think about a situation where infrastructure solves a narrow need but creates a broader pernicious problem: environmental damage, economic hardship for generations, etc. The timeless principle here is a healthy understanding of the service needs we are trying to solve, and the trade-offs involved in our proposed solutions – and indeed a calculation about whether in some cases it would be better to live with the problems.

• Infrastructure creates a long-term responsibility, with unforeseen obligations that might emerge only over time – arising through legislation, reporting requirements, or safety issues. Think for example of the difficulties of managing asbestos, which was once very much in favour. Once built, society will tend to want to renew infrastructure.

• Infrastructure will always have a political aspect. Public infrastructure requires funding by governments and will be attractive during electioneering. Suggestion: an independent central banking system has immunised monetary policy from most aspects of political influence except commentary. Are some lessons for infrastructure possible here? I am of course not suggesting a command economy, but perhaps a broad consistent policy climate could be created – analogous to the way objective renewal programs are supposed to stop jockeying for resealing of roads for influential people.

Current Methods

On the other hand, here are some of the temporary, current methods at our disposal to deal with the timeless principles. We know they are capable of adjustment, because they have been adjusted in the past.

• Funding mechanisms.

• Contrasting promises during elections.

• Technology.

• Legislation.

• Best practices.

Comment?

Do you agree with this division? With the ‘timeless principles’?

How can we apply these lessons from Information Technology?

What other areas might we draw upon for valuable lessons?

Welcome to 2018 and our January theme – “Get Ready for Change”.

Welcome to 2018 and our January theme – “Get Ready for Change”.

Who is this for?

To get ready for change we need to take it seriously. Over the years, as professionals, we have studied and built up an enormous wealth of practical experience. This experience has served us well, and much of it will continue to serve us well. But some won’t.

Sorting out what was valid, from what is still valid, requires us to challenge practically everything. This not only takes effort, it takes courage. What we know becomes part of who we are, so that challenging what we know seems as if we are challenging, even disowning, ourselves. Moreover, for those who are brave enough to challenge themselves, there is still the problem of disenfranchising friends and colleagues who are content to stay with the way things have always been.

For those who want to take up this challenge, to move ahead and ready themselves for the issues and opportunities to come, but who want to do so without offending colleagues and friends – try out your ideas here! This is a ‘safe zone’. Only those who are seriously thinking about the future comment here. Not everyone agrees, but everyone is prepared to think, to put forth their ideas, challenge those of others, and to be challenged in turn.

Re-thinking

Challenging what we know is an exercise in re-thinking. Here are some of the issues that we will be addressing:

- Re-thinking the aim of infrastructure investment (e.g. what do we mean by ‘public value’ and how do we create it?

- Re-thinking the players – who should be involved in the decisions? How do we involve more points of view? How do we ‘think forward’? (e.g. Citizen’s juries)

- Re-thinking the decision processes (tracking progress)

- Re-thinking the way we measure? (beyond the dollar?)

What else?

What are the issues that you consider we should be looking at in our attempts to get ready for change?

What is to come?

This is the last post for this month, and for our current theme on Adaptability in Infrastructure, but it is clearly not the end of the issues that we need to consider on this subject and so we will return to it later in 2018. Some of the issues remaining include:

Adaptability v Flexibility? Are they the same? Mark Neaseby suggests that it is dangerous for us to think of these terms as interchangeable. Flexibility has connotations of deciding now what may occur in the future and ‘building it in’. I think of the technical college in the UK that, allowing for a potential future need for super tall machines, built one of its instructional areas with extra high ceilings. The need never eventuated, but the cost of heating that building in the cold UK winters greatly increased their operating costs and reduced the use that could be made of that space. Adaptability does not mean that we decide NOW what will be needed in the future, but rather that we design so that WHEN we know what is required, we are easily able to change.

Adapting v Adaptability? Adaptability is a functional characteristic, and one that is going to be essential for future infrastructure design. Adapting is an action, and there is going to be considerable need for this as well, as we cope with infrastructure that is no longer suitable for its designed task, or where its designed task no longer exists.

Questions now include:

- What are the other key questions/ issues that you would like to discuss?

- What examples of successful Adaptation or Adaptability in design do you know of?

- Please share with us, who is working in this area and what are they doing.

Wishing everyone a most prosperous and exciting 2018! Please rejoin us January 9 as we now take a short seasonal break.

It still works!

‘Sure, the infrastructure is overdesigned/excessive at present but, with growth, it will be adequate in the longer term’. Thirty years ago, this was the accepted theory underlying much building construction, particularly in electricity generation. When you have grown up with a particular mindset, it is hard to shift it. Even when all the evidence points in the other direction.

At my first presentation on infrastructure renewal in 1987 I had a keen audience and question time went for over an hour. Then one fellow asked ‘With the technology we now have, surely we could make our buildings last for 300 years’. My response brought question time to a sudden close. What I said was. ‘My goodness! Why would we want to?’ Peter Erkelens, of the Eindhoven University of Technology, is one professional who has been considering this problem for more than a decade now and he has developed the ‘lifespan approach’. His view is that we should design and select the components and their connections in such a way that they function in accordance with the wanted lifespan.

He suggests we think in terms of the relationship between the economic (or functional) lifespan and the technical lifespan and that we look at three scenarios:

A. Economic life span < Technical life span.

The components of this infrastructure should be re-usable and/or recyclable

B. Economic life span = Technical life span.

The components should be recoverable and then recyclable

C. Economic life span > Technical life span.

The components of the infrastructure should be replaceable and recyclable

Peter Erkelens argues that ‘the design efforts should be such, that the resulting products are sustainable. This requires thinking about environmental effects and should include options for re-use, replacement and recycling’.

To see detailed ideas about how this concept can be applied to buildings, both offices and housing, See Peter Erkelens

Hein Aucamp, Director, WA Integrated Asset Management, and member of our Perth City Chapter, WA, continues his exploration of adaptable infrastructure.

The linear scarring of a redundant road and the tons of aggregate mean that the disposal cost is significant. So we tend to resist discussing that such a situation would benefit from adaptation; our problems begin in earnest when people agree with us and want to know how to do it.

The linear scarring of a redundant road and the tons of aggregate mean that the disposal cost is significant. So we tend to resist discussing that such a situation would benefit from adaptation; our problems begin in earnest when people agree with us and want to know how to do it.

I can offer a tentative suggestion in another direction, but applications may prove elusive. The most adaptable infrastructure is that which supports the services with the greatest degrees of freedom. For example, compare air transport with road transport.

Consider air transport. The physical infrastructure to connect Australian States by air is a small length of runways, some sophisticated buildings, and an expensive fit-out of smart electronic equipment with highly trained personnel. Every aspect is reconfigurable by procedures and routing schedules except for the landing and take-off points: and even these can be by-passed.

On the other hand, the physical infrastructure to connect Australian States by road is a byzantine spider’s web of expensive roads and bridges of varying degrees or repair. Compared to air travel, nothing is reconfigurable by policy except speeds or standards when reconstruction is done.

It is not always possible to transport goods and services by air rather than road; we will probably always need both.

But my tentative suggestion is that where possible, choose services with the greatest degrees of freedom, and build the infrastructure to support those services. Provide virtual library services. Choose wireless or satellite services rather than cable services.

Recent Comments