Some years ago, for SAM, Ype Wijnia and Joost Warners, both then with the Essent Electricity Network in Holland, argued asset management was a strange business. Consider, they said:

Some years ago, for SAM, Ype Wijnia and Joost Warners, both then with the Essent Electricity Network in Holland, argued asset management was a strange business. Consider, they said:

A typical Asset manager works with an asset base that is very old. For example, at Essent Netwerk the oldest assets in operation are about 100 years old, and the average age of the assets is about 30 years. Each year about 3% of the asset base is either built or replaced. Typical maintenance cycles have a period of about 10 years. So, about 13% of the asset base is touched on a yearly basis.

This means our basic job is more like staying clear of the assets and letting them perform their function than it is like actively doing something with them, as the term Asset Management suggests. Therefore it might be wiser to call ourselves asset non-managers.

The strangeness of Asset Management increases further if you look at the portfolio of asset and network policies. From long experience with managing assets, most policies have reached a high level of sophistication and they address not only the general situation but all kinds of possible exceptions which have been encountered over the period since the policy was put in place. Those exceptions have exceptions of their own, requiring further detailing of the policy.

In the life cycle of a policy, attention therefore drifts from the original problem to managing exceptions. This means that as the sophistication of the policy grows, the knowledge about why the policy was developed in the first place diminishes.

Exaggerating a little bit you could say that Asset Managers do not manage most of the assets, and in case they do, they haven’t got a clue why they are doing what they are doing. You would expect a system that is managed this way to collapse very soon, but somehow it does not, as the electricity grid in Europe has a reliability of about 99.99%.

However, this way of managing assets can only work in a stable environment with stable or at least predictable requirements for the assets. Unfortunately, the world we live in is nothing like stable.

Thoughts?

In our current data driven environment, there is still a role for common sense

In our current data driven environment, there is still a role for common sense

A few years ago, using its renewal model, a council was advised that its buildings were 60% overdue for replacement. This came as a great surprise to the Council – but should it have? If true, one would have imagined that there would be many visible signs of major deterioration – non-habitable buildings boarded up for safety, signs of breakdown in buildings still in use (e.g. lifts, plumbing or HVAC not working), union demonstrations, protest movements, etc. If true, this should not have been any surprise to council, their own user experience would have told them that it was true. So what is happening here?

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.” Statistician George Box.

Jeff Roorda, in his post asked ‘why focus on the measurement of physical life using condition instead of looking at function and capacity?’ A very sound question. Function and capacity determine economic life, or useful life (how long we can expect the asset to be of use to us) rather than how long it will physically last. His question is part of a wider range of questions about how we use models.

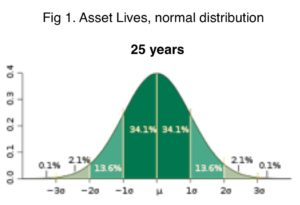

The first thing to note is that renewal models are financial models. They are based on averages of a group and say nothing about the time to intervene (i.e. replace) for any individual asset. When we say that an asset, or an asset component, has a useful life of 25 years, what is really to be understood is that assets of this type may fail at 15 years or even earlier and perhaps as late as 40 years or more but that when we take them as a whole, their useful lives will average out to about 25 years. This is a guide to financial planning.

Because 25 is an average (and assuming we have a normal distribution and not one that is severely skewed) then we can expect that half of these assets will fail before the age of 25 and half will fail after the age of 25, as shown here in figure 1. Thus we cannot assume that just because an asset is greater than 25 years that it is ‘due for replacement’

This is the mistake made by the council, and why it came as such a surprise to the Councillors.

Our instincts may not be infallible but when intuition clashes with the results of a model, it pays to check both our understanding – and our interpretation of the model.

While we eagerly await Jeff’s next episode, let’s consider the following example of City West Water that realised that ‘strategic’ and ‘operational’ didn’t have to be in opposition. This happened many years ago, but the message is just as relevant today.

While we eagerly await Jeff’s next episode, let’s consider the following example of City West Water that realised that ‘strategic’ and ‘operational’ didn’t have to be in opposition. This happened many years ago, but the message is just as relevant today.

When Melbourne Water was broken up into a headworks company and three distribution companies, City West found itself the owner of the central and oldest part of the network. One of the earliest problems it had to deal with was the repair/ replace decision. Clearly it could not afford to replace every ageing asset that was giving it problems.

On-the-ground decisions had to be made taking into account not only the condition of the asset but future rehabilitation programs and a range of other strategic considerations. This meant that maintenance crews found themselves assessing the condition of the asset, determining the problem, but unable to operate until the information had been fed up the line and assessed by the strategic asset managers. This was costly, delayed action and frustrated the maintenance crews.

The Strategic Asset Manager decided that in the ‘need to know’ context, the maintenance crews needed to be aware of the strategic decisions that affected their actions. So he ran a series of sessions in which he explained not only the strategic decisions that top management had come to – but why they had made these decisions.

Discussion was apparently quite lively. He answered all the men’s questions and then went with the men out on site. He asked the crews to assess the situation and then recommend the action required, in the light of top management strategic thinking. Within a short period he found that they were making the decisions that he would have made

– and then he let them run with it.

Comment?

Today’s post is by Jeff Roorda, Technology One, and Deputy Chair of Talking Infrastructure.

Is using condition to determine life a fundamental error in asset registers?

Part 1

How long does an asset last? The answer determines life cycle cost, depreciation and infrastructure planning.

Asset registers estimate useful life for every asset but which life do we use? The physical life or the economic life? Yes these are different, and often materially different. I recently was working in Queenstown NZ with Queenstown-Lakes District Council. After work, I boarded the steamer TSS Earnslaw that had been carrying passengers on lake Wakatipu since 1912, and its steam engine is still powered by coal. The Earnslaw and many steam powered transport assets around the world still have many years of remaining physical life after over 100 years of operation.

So why did we stop using steam for transportation ? Was it because the assets reached their physical life?

In hindsight we all know the answer. Because steam power is dirty and technology made steam power obsolete. OK then, so the economic life was determined by function and capacity, not by physical condition. Even though steam powered assets had many years of physical life remaining, they became obsolete relatively quickly, far more quickly than most people managing the assets predicted. How much of the infrastructure we are building right now will be obsolete well before physical life is reached? So why do we focus on the measurement of physical life using condition instead of function and capacity? The pace of change could be faster now than in the 1940’s and 1950’s when transport shifted from steam to the internal combustion engine which created the infrastructure networks we now manage.

Think about what we are building now and drivers for change.

Infrastructure based on continuing the past where everyone has to travel to the office at the same time creating peak transport loads using internal combustion engines with one person per car does not seem to be a likely future with changes in communications and energy technologies.

Part 2 coming shortly.

Just over a year ago (Jan 6 2017), I wrote about ‘Pop Up’ Prisons, more accurately called ‘rapid build’. Rapid build is used in war zones where there is a sudden and urgent need. It is extremely expensive. Overcrowding of our prisons had led to this now being considered an urgent need, but why had we not foreseen it? One answer had, in fact, been earlier suggested by Mark Neasbey in his post “Infrastructure decisions we make when we don’t think we are making any”(Aug 12 2016) where Mark had brilliantly, and entertainingly, explained how the ‘costless’ decision to put more police on the streets to combat crime had cost consequences which were not only extensive, but, unfortunately, invisible in the eyes of decision makers.

Just over a year ago (Jan 6 2017), I wrote about ‘Pop Up’ Prisons, more accurately called ‘rapid build’. Rapid build is used in war zones where there is a sudden and urgent need. It is extremely expensive. Overcrowding of our prisons had led to this now being considered an urgent need, but why had we not foreseen it? One answer had, in fact, been earlier suggested by Mark Neasbey in his post “Infrastructure decisions we make when we don’t think we are making any”(Aug 12 2016) where Mark had brilliantly, and entertainingly, explained how the ‘costless’ decision to put more police on the streets to combat crime had cost consequences which were not only extensive, but, unfortunately, invisible in the eyes of decision makers.

Now, today, comes news from America where incarceration rates have increased 500% over the last few decades. Philadelphia in Pennsylvania is even more extreme, their incarceration rates have increased 700% in the same time. But that is already changing with the appointment a few months ago of a civil rights lawyer, Larry Kranser, as the new District Attorney who is taking extreme action to reduce the cost and human damage involved. The whole encouraging story can be found on the Slate website here but I would like to draw your attention to one move which could effectively be used more widely.

“In a move that may have less impact on the lives of defendants, but is very on-brand for Kranser, prosecutors must now calculate the amount of money a sentence would cost before recommending it to a judge, and argue why the cost is justified. He estimates that it costs $115 a day, or $42,000 a year, to incarcerate one person. So, if a prosecutor seeks a three-year sentence, she must state, on the record, that it would cost taxpayers $126,000 and explain why she thinks this cost is justified. Krasner reminds his attorneys that the cost of one year of unnecessary incarceration “is in the range of the cost of one year’s salary for a beginning teacher, police officer, fire fighter, social worker, Assistant District Attorney, or addiction counselor.”

The same reasoning could be applied to just about any new rule or regulation introduced by government.

Comment?

This is a brief account of a lengthy 2014 dialogue I had with Patrick Whelan, a thoughtful architect in WA. You are now invited to join the discussion.

This is a brief account of a lengthy 2014 dialogue I had with Patrick Whelan, a thoughtful architect in WA. You are now invited to join the discussion.

Patrick: In WA, a scoring model was devised and adopted for all police buildings, It scored building fabric condition and the condition of services to determine an overall condition score. The building’s suitability for purpose was then determined by comparing scores for compliance with the Building Code of Australia and for compliance with the Police Building Code (the agency’s accommodation standards) Comparing the Condition score with the Suitability score enabled a ‘works priority score’ for the station, in effect displaying a level of service offered by each station.

Penny: Whilst building condition and code compliance are important, they are important from the perspective of the building maintenance manager. To get at the idea of service perhaps we need to look at what the building user wants to get out of the building. A building may be in excellent condition and meet all code conditions, yet still fail to work efficiently for the user. It may be that the design is no longer suitable for the new work that needs to be carried out, or it may have the wrong capacity – either too much or too little. It may be in the wrong place!

Patrick: In the case of the WA Police, their Building Code articulates everything needed of a building to progress policing: Planning criteria, technical criteria, functional relationship diagrams, room data sheets, formulae for calculating room sizes and the number of ablutions facilities, guidelines for the compliant design of custodial facilities, etc. The Police, being a paramilitary organisation, have a very strong handle on what is needed to do the job. However, things change over time, and the building code changes with them.

Penny: Building codes are so efficient because, in the short term, people only need to respond, ‘on the dotted line’, as it were: they don’t have to think. However can what makes for short term efficiency lend itself to longer term ineffectiveness? What can be done to determine a code that is both efficient and effective?

Over to you!

We all know early option analysis makes sense so why don’t we do it?

We all know early option analysis makes sense so why don’t we do it?

Maybe there is a desire to ‘get runs on the board’, to be able to show the media, as well as government sponsors and promoters, that ‘something is happening’ and that the team assigned to the task are not dragging their feet. While a project is in the early options appraisal phase it requires a lot of flexibility – and time – from senior executives, who are the only ones who can determine when sufficient evidence is presented to enable a choice to be made as to the direction to be taken. Once the direction is chosen the work can be passed to lower levels or consultants to construct the ‘business case’. Experience with the Victorian Investment Logic Mapping work confirms the difficulty of getting senior executives to spend the necessary time on this high level decision making.

Danger of default to ‘the infrastructure solution’

In 2000, according to the UK Institute’s Report “What’s Wrong with Infrastruture Decision Making”, there was an analysis of the environmental impact of intermittent discharges of storm sewage into the Thames. They concluded that “The main problem with the early options analysis was that a mixed solution (using a combination of smaller measures to address storm sewage) was not considered in detail . This is an example of the seeming preference within government for large projects.”

The tunnel, now under construction, has a total cost of £4.2bn and will add an estimated £15-25 a year to London water bills until 2023/30. Critics say that the cost is unnecessarily high and that cheaper alternatives were never explored properly. The Institute argues that decision makers on the project may have fallen prey to perceived political risks, staff fears of expressing disagreement and decision-making processes sceptical of innovation, which made decision makers reluctant to turn back after making an early commitment.

So our inquiry today is:

-

Why don’t we do, what commonsense says we should?

-

What experiences have you had that illustrate a too quick default to the infrastructure option.

-

And what can we do about it?

DeBono invented the term ‘Po’ for a provocation – something that begged to be thought about and commented on!

DeBono invented the term ‘Po’ for a provocation – something that begged to be thought about and commented on!

In this light, my friend, Miso, has submitted the following:

“With respect to managing infrastructure, the shortcut to “a more enjoyable trip” is to say that rather than expanding resources on collecting more condition data, let’s “recycle” (actually use for the first time) the mountains of information we have produced through decades of decision making.

By analyzing patterns in financial, engineering, and administrative data we can derive the comprehensive infrastructure performance measure. One which inherently accounts for all factors (e.g. conditional and functional) which were taken into account when the professionals made their decisions.”

Your Thoughts?

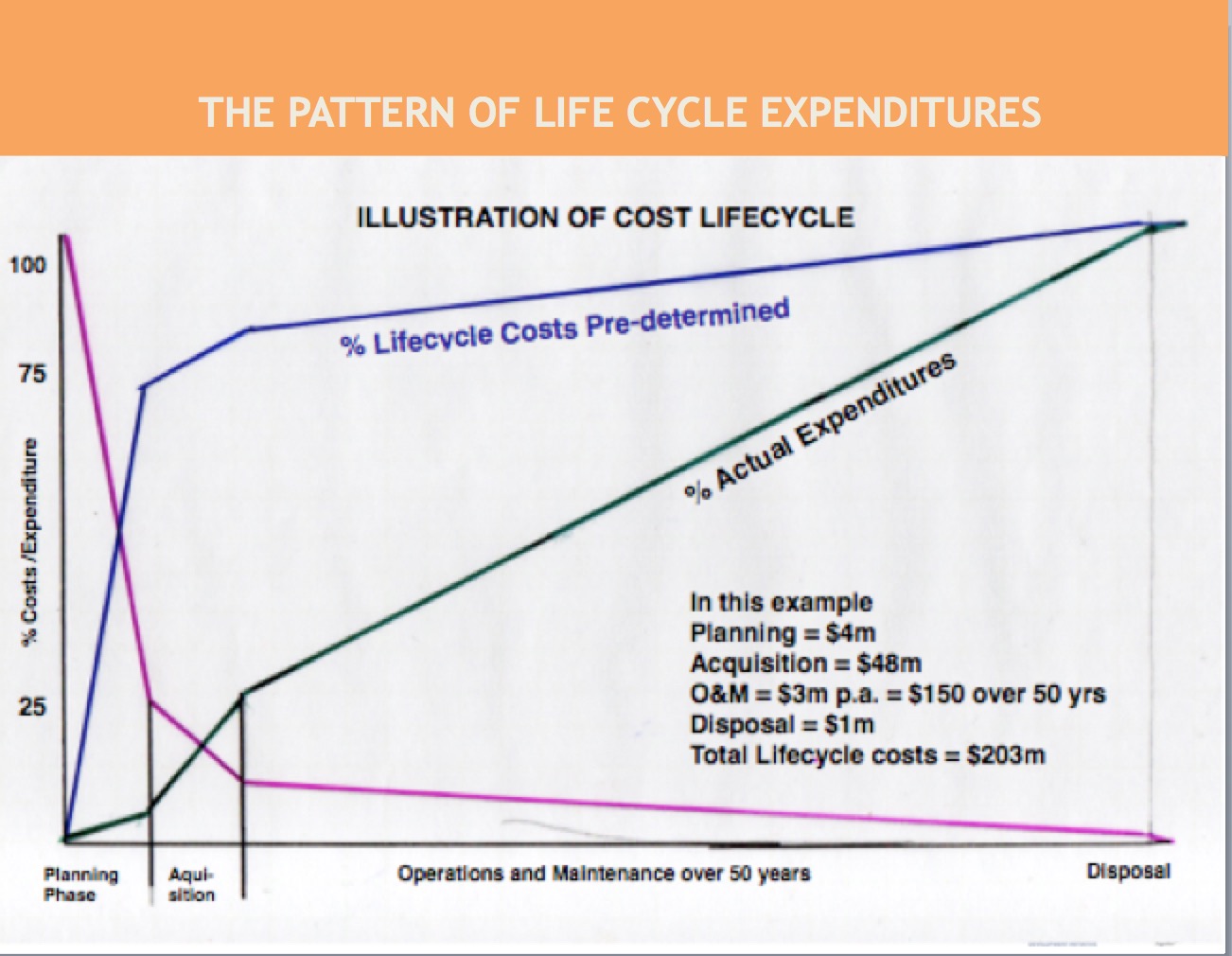

18 months ago I had the pleasure of co-designing and presenting a capacity building workshop for Auditors-General in the Pacific Islands. The subject of the workshop was auditing for the better management of public assets. We looked at the 4 stages – planning, construction,operations & maintenance and, finally, renewal or disposal – and discussion revealed that the auditors chose to spend the bulk of their time in analysing performance at the operations & maintenance stage. This made sense. It is by far and away the area where most expenses occur. However, it is not the stage where most expenses are committed. That occurs much earlier, at the planning stage. This is the stage where the nature, location and size of the project are determined and these are the primary determinants of how much will be spent later at the operations and maintenance stage.

I drew up a hypothetical schema to make the point. It showed that, by the end of the first or planning stage, only $4m of the total life cycle costs ($203m) had been spent BUT, the decisions made during this phase had already committed about 75% (and sometimes more) of the total costs. In the diagram the green line represents costs actually expended, the blue line costs pre-determined and the purple line represents the scope remaining to make a difference to total costs. This shows that by the time the plant is commissioned and operational, there is really relatively little that can then be done to improve on the overall life cycle costs.

The figures I used in this example are fictitious.

They are consistent with the theory and principles of life cycle costing as shown in the major textbooks on the subject.

I would have liked to use real figures but I couldn’t find any. So I contacted people who might be expected to know – key academic figures in asset management, experienced consultants, long time practitioners. But no, no-one could help.

So my question today is:

Why do we have so little actual data about this very key and critical stage of decision making? And how can we improve our knowledge – and thus our performance?

In the last post “The Infrastructure Quiz” I asked what the ‘purpose’ of infrastructure is. What did you choose? If you ask this question of most people, the answer is obvious – it just isn’t the same answer for everyone!

Have a look at the following possibilities:

- For asset managers, the answer is obvious – it is to provide needed services that underpin the economy and society well being.

- For economists in the Treasuries, the answer is equally obvious – it is to kickstart the economy. (For many years we had a stop-go policy for infrastructure. Whenever the economy got overheated, governments would cut back on infrastructure spending, and whenever it slowed down, they would spend more. There was a period in the early 2000s when this was recognised for the damage it caused. But now it seems to be back again.)

- Politicians and Think tanks are the ones likely to claim that infrastructure – ‘increases productivity’ and ‘raises the standard of living’ (but they seldom spell out exactly how, for it is all regarded as self-evident.)

- For the general public (most of whom could not give any examples of infrastructure beyond roads, if that) the answer is that the purpose of infrastructure spending is to ‘create jobs’.

- Military and strategic planners often see the construction and location of infrastructure as a strategic control problem. Many politicians do the same.

- The construction industry and its lobbyists strongly believe that we not only need infrastructure to keep the industry afloat but that we need to forecast what infrastructure and where in order to enable them to plan.

So, many purposes – all ‘self evident’!

Recent Comments