Photo by Сергей Гладкий from Pexels

A single source of truth

As digital transformation expands, there has been pressure in the field of asset management to consolidate, structure, reformat and create new data and align it with the business processes to create a systems approach for informed decision making, with the aim of providing structured data that can become a single source of truth for organisations and enable quality decision making for delivering value to the end user. Many providers of Asset Information Systems and IT promote this as their goal.

Logically, can there be a single source of truth?

While I am definitely in favour of IT solutions (#More code, less cement), I am struck by that phrase “a single source of truth” and ask myself ‘is aiming for it missing the point?’ We have, for a long time, argued that good decision-making requires good evidence. But good decision-making, as we are coming to recognise in these difficult times, is multi-layered and this means that the evidence needed for these decisions must also be multi-layered. No matter how clever our IT, we cannot rely simply on the information we can generate within our organisations, but we need to look without and beyond.

Consider what we have now learned from Covid 19

As the world has watched – and felt – the impact of Covid 19 in recent weeks, we have developed a new respect for Experts and the data, analysis and evidence that they can provide to help us feel our way through this problem. I say ‘feel’ advisedly. Because we are like the blind here, and will need to zig-zag our way forward, trying something and then retreating if the infection rate rises.

First there was a infection pandemic – a health problem. Here in Australia we responded with a national lock down that has been hugely effective in curbing the rate of new infections and thus deaths. But now we have an economic problem as 1.7 million are thrown into unemployment and factories, wholesalers and retailers are standing idle and interstate and international travel and thus tourism halted.

The government has sought to ease the impact on unemployment with its job keeper and job seeker allowances and this has been sound thinking. But later it will need to decide what to do with the debt it has incurred – a public finance problem. No-one knows how long the support will last or when they can go back to work. Many, particularly the most vulnerable casual workers, are not covered. Anxiety rises. Authorities are now anticipating serious mental health problems and a rise in domestic violence.

Sporting events have been cancelled and resumption of them is a major talking point in the media for all of us who would normally attend the football on the Saturday and yell and scream for our teams, (and discuss it endlessly on Thursday, Friday and Sunday) no longer have this opportunity to break tensions, relax and cement social relationships. The arts are particularly affected as few arts workers fall within the protected jobs range. What are we without the arts, without sports?

Yes economics is important. But it is not the only thing that is important.To solve a multi-layered problem it is not possible to have ‘ a single source of truth’

Now let us return to Asset Management.

Is it possible to make decisions based only on clever IT applied to our assets? That may enable us to determine our internal supply costs – but outside in the world how do we know how much will be demanded? What external costs – and benefits – will our actions create? What impact are we having on the mental health of our workers and on the environment? We may be able to make a profit in the short run but what of our resilience in the face of change in the slightly longer term?

Asset decisions are thus also multi-layered, so can Asset Managers really expect that in serving all their stakeholders they can rely on data for ‘a single source of truth’ – no matter how cleverly calculated? Or do we have to come to terms with the fact that all of life is a trade-off? And thus consider how we learn to deal with trade-offs?

If not a single source of truth, then what?

An important question! Talking Infrastructurebelieves that more is required of AM Leads than simply to follow an IT algorithm or a one point source of information. We need to be able to think through the ‘cumulative consequences’ of our decisions, and to that end we are developing “The toolkit for Leads” specifically for those who head up our asset management teams (or aspire to) and see themselves as being a more forward thinking and active part of their organisation’s decision making.

If you would like to know more, sign up now to be a member of Talking Infrastructure (it’s free) and we will advise you as soon as it comes online and keep you up to date with additions.

How can you plan for the unknown – when you literally cannot see your own hand in front of your face? Well, back 12 years ago, when she headed up the Strategic Asset Management Team at RailCorp (now Sydney Trains) I facilitated a scenario planning exercise for Ruth Wallsgrove. The scenario we looked at was an epidemic with an immediate impact on ridership, with everyone – although, of course, we didn’t call it that – ‘social distancing’. Now over to Ruth to look at the implications that has for us today. PB.

The importance of planning

“Emergencies are overrated as a response mechanism. Are preparation, prevention, and planning about to become more popular alternatives? Can we nudge this? “

Planning – that is, thinking ahead and co-ordinating what we are going to do – appears to be central to dealing with Covid-19. We do not know for certain what the conclusions will be, except that South Korea seems to be doing well, and the USA not.

The nature of planning

I teach AM to a lot of people, and quite a lot of them ask how you can plan when you don’t know exactly what’s going to happen. The answer is, of course, that it is even more important to plan when you don’t know exactly what will happen. The point is to give yourself a framework for flexibility. No planning ahead at all gives you nothing to work with.

It would not have been a sensible plan to stockpile ventilators. And there was no possibility to stockpile Covid-19 test kits, because they didn’t exist. Good planning instead would be putting in place the thinking processes that would enable us quickly to ramp up production of known equipment, and to come up with new tests and vaccines.

Scenario Planning

Scenario planning seems to me to be the opposite of Planning with a capital P: the opposite of a high up committee coming up with a visionary Plan for transforming our infrastructure.

The idea of scenario planning is to look at alternative scenarios, and ask what the data tells us. It’s to consider what to do if the future doesn’t go the direction you want it to. What you can influence. How you can stay nimble to respond to what reality tells you.

The Chain of Consequences

In our scenario planning session in 2008 we were asked to consider – Could an epidemic lead to an increasein ridership?

Trains and buses are currently empty not just because people don’t want to be in a small space with many other people, but because many of us are in lockdown. Our workplaces have closed and, if we are lucky, we are working from home. (If we are not… we are out of our paying job, temporarily or permanently).

What if: people go on being nervous about crowded spaces after we go back to whatever the new normal is?

Well, one possibility is that everyone heads to their cars with a vengeance. But what if that led to impossible traffic jams, as most cities already had no spare capacity for personal vehicles?

What if: someone comes up with a neat way to avoid breathing germs on each other? This was one of our scenarios. How could the chain of consequences lead to an increase in ridership? It’s not even hard to do, once you free yourself from thinking you ‘know’ what people will do, or should do, in future.

Along with scenario planning, we also need the skills to go beyond the immediate, and ask what the knock-on impact of one event on another. Such as the basics of AM: if I build this rail line, what will that mean for operating expenditure for the next thirty years? What does it mean I can’t do, because I’ve dedicated resources to this rail line instead of that arts centre? What are possible impacts on our overall capabilities – including the environment? (There is always another Plan, but no Planet B…)

The role of Asset Management practitioners

In late 2018, when a wire down led to a wildfire that burned down a town in California, much attention was paid to control the spread and mitigate the fallout. The AM team were involved, however, not in initiatives to look at the urgent immediate risk, but rather in the important task of what to put in place to reduce such risks in the future. So often, as we know, the urgent drives out the important.

We are not emergency planners; that’s an honourable discipline in its own right. Our job is to consider scenarios and chains of consequences (“and then what?”) and building flexibility into our asset systems and our processes.

And our Question Today:

What steps can we, as Asset Managers, start taking to prepare for the next pandemic?

We all admire the excellence of precision teams like the Red Arrows, the RAF Aerobatics team. Sheer magic! But, believe it or not, your job in building an asset management team is harder! This is the fifth and last excerpt of “Building an Asset Management Team” by Ruth Wallsgrove and Lou Cripps. Sorry about that! But you can now get the whole thing from AMAZON. No Asset Management team should lead without it!

Five: What is required of the AM lead?

AM is as much a business and communication function

as a technical one in practice.

Whoever you select to run the AM team, they must have:

1. Some good team management skills – or be actively developed in these

2. Communication skills to communicate and co-ordinate both upwards to senior leadership and external stakeholders (for example Boards for public agencies and other politicians), with delivery functions, particularly closely with Maintenance, and with key support functions such as Finance, Procurement, and IT. They have to take the main responsibility for buying the organization into good practice AM processes.

3. The ability to inspire the actions of others towards a common aim. Not only is AM about alignment to shared targets, it’s also hard to implement, and so needs people who are inspired.

4. Understanding of the importance of good business processes themselves!

We would also include be willing to be wrong, and continue to move forward.

It should go without saying that they need to understand Asset Management, and at a minimum this means they have been through some training. Recruiting someone from another organization who has already done AM is of course a great idea – if you can find them. Demand wildly outstrips supply of experienced AM practitioners in North America, and indeed elsewhere.

Who is selected sets the tone and will need to lead the effort

up and down the organization.

Lou: they must be a leader and not just a manager. This will include knowing the direction to take the team and the abilities to get others to want to help get there. They protect and care for the individuals, the team and believe in the cause themselves.

The lead is not required to be the technical expert: they have to be okay with surrounding themselves with experts who know more than they do.

!Warning!

You are building Asset Management practitioners and leads for others!

If you build a good team, there is one thing you need to prepare for: that they will get head-hunted away by other agencies looking for someone with real Asset Management experience. This just happened to RTD’s AM Division.

Both of us find this personally painful – we tend to love our teams and the good people in them – but of course it is part of developing good AM more widely. It’s probably wise to assume that, since some of them will move, it’s worth encouraging them in good management and leadership skills all along. And you have to want the best for the individuals on your team, otherwise you won’t be a good lead yourself.

Some thoughts on AM team culture from Lou

I am extremely fortunate to work with great people.

But a good team isn’t just a collection of good people, although that is a huge part. To build the right team, we need to be clear on what the team would do, and what ‘we’ wouldn’t do. How will we work together to achieve collective goals: team culture.

Essentially, we need to do this through a Plan-Do-Check-Act approach:

•Clarity about the enabling attitudes – a vision of the target culture, and a clear sense of what the culture is at the moment and how it falls short of what’s needed

•Communicating and encouraging these in different ways to reach different groups

•Actively look for ways to measure and monitor this change

•Review and adjust change strategy from lessons learnt

We have to create the right environment, where it is ‘safe to explore’: creating enough safety for people to be happy to go out in to the new, the unknown. There are some rules, and the leader will play a fair referee on them.

Asset Management is not the only area in our society that can have challenges with experts. We don’t mean that we need less expertise, or should not listen to people who know more than we do. But an increasing amount of research suggests that people who identify as experts come with their own blind spots; and that being smart and well educated, and knowing it, can make for worse, not better decisions.

The real issue is assuming you know more than you do – lacking humility about what you don’t know, and believing that what you know is enough. ‘To the man with a hammer, every problem is a nail.’

In the world of asset decisions, no one person ever knows enough.

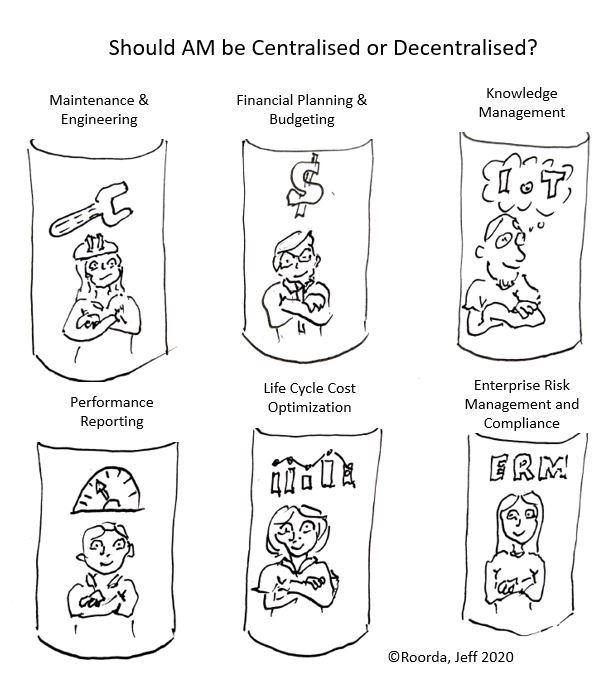

Whether asset management should be centralised or decentralised has been asked since the beginning of Asset Management (AM) as a structured activity. Many organisations have cycled through these structures, some several times. We have seen both models succeed and struggle. Before considering which organizational structure is best, we can learn from what has worked in the past.

The common primary success factors are a good asset management team leader with top management (ISO, 2014) support and commitment over the long term. Without both of these in place, fragmentation into silo’s of finance, maintenance, construction, compliance and knowledge management is the most common result. Often these silos are in adversarial competition for resources with short term horizon of less than 5 years.

The key focus of the ISO 55000 series and IIMM is the role of the AM Leader and the interaction with “top management”. Leadership is not the same as management although they are complementary and often overlap. (IIMM, 2015). A secondary, but essential success factor is at least 2 people who are proficient and have experience in asset management. (Wallsgrove, 2020)

With these success factors in place, that is, top management commitment, a good AM leader, and at least 2 people with AM knowledge and understanding, a centralised structure has a lower likelihood of fragmentation into the AM silos mentioned above.

Good communication skills are the essential attributes of a leader to communicate throughout the organization how the organizational objectives are to be converted into asset management objectives (ISO 55000 2014, 3.3.2). This manages the primary risk of fragmentation of asset management into competing silos with fragmented or inadequate skills.

Both international source documents, ISO 55000 series and IIMM are consistent in defining the roles and responsibilities of asset management in an asset intensive organization as much more than maintenance management.

References

IIMM, I. I. (2015). IIMM International Infrastructure Management Manual.Sydney: IPWEA.

ISO. (2014). ISO55000.Geneva: ISO.

Wallsgrove, R. and Cripps, L. (2020). Building an Asset Management Team .Amazon .

AMQ International’s ‘Strategic Asset Management’, ed: Dr PennyBurns, Issues 270, 298, 371

Footnotes

1. SAM 270 looks at different structures, all of which were adopted successively by an Australian Rail Company when they discovered the problems with the one they were currently using. The whole issue looks at organisational structure.

2. SAM 298 pp 3-5 ‘Four models of AM organisation within councils’

3. SAM 321 ‘A Perfect AM Organisation?’ pp 1-3

4. Roorda (JRA) was the Asset Management Consultant for BART from 2012 – 2015 and established a successful asset management programme for BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) with John McCormick and Frank Ruffa. AM Council News and Asset Management Implementation and Integration Frank Ruffa

This book should be in every AM office, and at less than $9.99 it won’t even make a dent in your budget. So do it! Here is the Amazon link. Need more encouragement? Then read our 4th excerpt and find out who to have in your team.

Four: What kind of people does an AM team require?

Considering what is required – and the world now has nearly 30 years’ experience of what it takes to make Asset Management work, starting in Australasia and from the late 1990s in Europe – it is not surprising that dedicated AM roles do not suit everyone, and many organizations have made some mistakes in their AM appointments.

It is also true that the different requirements of a well-rounded AM team will always make it unlikely, even undesirable perhaps, that one individual would hold all the necessary skills and experience. Instead, we need each team member to have confidence in their own strengths and complement each other towards a common purpose – very much like the ideal Asset Management organization writ large.

Any AM team requires a balance of people.

- Asset Management is a bridge between business strategy and technical delivery, and therefore must consider the right balance of attributes and skills to deliver this.Bluntly, an Asset Management team that is purely technical, or alternatively has no experience with assets, will struggle. Some experience in the team on front line delivery and, even better, existing relationships with the front line, especially maintenance, is invaluable, but AM also needs good analysis skills and business understanding.

- More challenging for some technical people is the need for good communication skills. Since AM implementation is hugely about communicating what AM is about and facilitating the improvements, AM practitioners must at least value communicating.

- AM functions have to see themselves as promoting, influencing and coordinating rather than directly delivering. (Wally Wells of Asset Management British Columbia calls this the folded arms approach.) This means developing good relationships with a range of other teams. AM practitioners have to be able to acknowledge and respect what other people know, and have some detachment, because their role is to bring together different teams and types of experience & knowledge into asset strategies and integrated planning, not to try to impose their own opinions on asset decisions. They must have a big picture view of the business such that they understand concerns within silos but can explain the needs of the entire organization to put the concerns into context.

- Another specific requirement is for people who can ‘embrace uncertainty’, since AM is at its heart about planning for the future – and the future is always uncertain. For example, ProGas in the Netherlands in the early 2000s focused on promoting smart technical people into asset planning: the only ones who succeeded were those who could cope with making decisions on clearly imperfect knowledge and data. Many could not.

When Penny Burns took the RailCorp Strategic Asset Management team managers through Scenario Planning training, the most important outcomes were making everyone feel a little less certain about the future for the railway – and set us to thinking hard about what data would indicate a real trend.

- The ability to think probabilistically is not intuitive, but it is of great value and can be learned. Those that have developed their understanding of probabilities can use this thinking to help address the uncertainty that is essential to describing systems, predicting outcomes, and influencing outcomes.

- A structured approach to problem solving, even to questions where there isn’t an obvious right answer, or the exact answer can’t be known, is important. AM practitioners should be curious and ask questions, working to discover root causes.

The strongest AM practitioners seem to know when there isn’t a single correct answer, and what set of constraints should be used to move forward with the next best alternative.

An Asset Manager has to be comfortable saying, “I don’t know.”

- It’s also vital to be able to see what is important, the AM principle of criticality, and the balance of ‘cost, risk and performance’ in what we do ourselves.

- AM implementation is about change, so generally will not suit anyone who primarily seeks stability or following the old rules. We need people who have some social skills and ability to build good working relationships, at the same time that they will push for change, in other words stand up for new ways of working.

- Continual improvement requires a desire to learn new concepts and ideas, even when the evidence overturns what you expect. Continual improvement requires a place of pause and reflection before the next Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle is commenced.

- Leadership skills to get others to buy into our new ways of thinking and working.

And the ability to balance the natural tensions that exist between all of these skills….

This is hopefully not to completely depend on unicorns – or platypuses – that we may never find.

We are looking for an odd and tricky combination of attributes. Instead of searching for a very rare and sought after amphibious, duck-billed, otter-footed, egg-laying, beaver-tailed, venomous mammal that locates pray through electroreception – it’s easier to provide all the things we need through a complementary team.

It is also important to understand what skills we don’t need because they exist in other areas and within the asset class groups. We don’t need to be experts in all areas if we can coordinate with others.

RTD’s AM Division looks for these attributes in everyone it hires:

- Highest ethics and integrity

- Cognitive ability

- Objectivity and self-awareness

- Basic numeracy

- Effectiveness

- Curiosity / lifelong learner

- Problem solving

- Humility

- Initiative / motivation and grit

A good sense of humor also helps.

Sometimes you ask a question and the answer is unexpected but once read, so completely obvious, you feel an idiot for not seeing it in the first place. Read this exchange on bushfires (and value) between Jeff Roorda and me – but mostly Jeff.

Jeff:

The devastating fires that have blighted Australia in 2020 have now burnt through 18.6 million hectares of land. The fires had a total perimeter of 19,235 kilometres. That’s the equivalent distance of Sydney to Perth four times over and further than Sydney Australia to Los Angeles USA.

An estimated 1 Billion animals were killed, and entire species or plants and animals may have been wiped out. 33 people died and 2,779 homes were lost.

The cost to fight large fires is very high and growing with questions about the effectiveness of reactive strategies. We have avoided putting a value on air, fire, water and earth because it doesn’t neatly fit into our built infrastructure silos.

A large fire shows not only the connections of our artificial silos, but is instructive in a better understanding of value, cost, benefit and risk. These are the inputs to asset management plans. Decisions can then be based on scenarios based on evidence, expertise and experience to come to a wisdom decision for future generations.

We understand cost and cost and value are connected. The cost to react to crisis is high and growing but cost should be based on an asset management plan that has benefit, cost, risk and value of decision scenario options.

Penny:

Fires do not confine themselves within council boundaries, or even State boundaries and this was amply demonstrated in our recent (indeed still current) fires. Asset management plans are necessary but they are, sadly, not sufficient. How do we go further?

Jeff:

If any future event is identified then there are options to mitigate that event. Examples are a large fire, reliable energy or water or infrastructure congestion or under utilisation. Not making a decision or not having an evidence based asset management plan with possible scenarios is actually a decision to run to fail.

This often happens because we think we can’t reliably measure value. But when we get to the point of run to fail we can measure cost. In 2017, the NSW Government invested $38 million over four years for three Large Air Tankers to be used in firefighting efforts. In December 2019, the Federal Government announced $11 million on top of the annual $15 million. Add to this State and Local Government Costs and the opportunity cost of over 72,000 members just in NSW.

So there is a connection between cost and the value we put on something. Concepts such as deprival value and service potential become useful. Cost is a proxy for the value of what we lost, human lives, houses, businesses, over 1 Billion animals died and some flora and fauna may be extinct. A better concept of value is essential to making long term decisions for future generations.

For your weekend reflection over a cold beer – or libation of choice.

In 1999 my friend and colleague, @KC Leong, organised the first AM conference in Malaysia. It was held in Kuching, Sarawak. Not only was asset management very new but even the concept of an asset was pretty new so that the Minister opening our conference felt that he needed to explain what an asset was. ‘An asset’, he said, ‘is anything of value’. Then he paused, thought for a moment, and added ‘ and also anything not of value’ for, he explained ‘ it could become of value later’!

But what does it mean to be ‘of value’ ? This is something that we started exploring last weekend. I learnt a lot from our discussion and sincerely thank @Adam.Lea-Bischinger, @Gosh Jacewicz, @Ruth Wallsgrove, @Gregory Punshon, @Christopher Silke for their contributions. What this showed, is that we cannot simply assume that all infrastructure is (a) ‘of value’ and (b) certainly not ‘of equal value’. So how do we decide what projects should get our attention?

Today I would like to take this further by considering some of the arguments presented by Mariana Mazzucato. Mariana is an Italian-American economist whose research into the eocnomics of innovation and the high technology industry revealed that far from the private sector being the wellspring of all innovation, nearly all of the significant innovations that are now in common use (and just about all of the features of the iPhone) were actually developed in the public sector. She does not detract from what the private sector has done with these innovations but she does bring out the importance of state investment, which has featured so heavily, especially in the early, high risk stage, so necessary to subsequent development. In her first book ‘The Entrepreneurial State’ she debunks the myth that the State is merely a dull and stodgy administrator and shows that much of the real innovative work is done in the public sector.

Consider Australia’s own CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation). From its development of wifi using complex mathematics known as ‘fast Fourier transforms’ as well as detailed knowledge about radio waves and their behaviour in different environments, to Aerogard developed way back in 1938 and now used by Mortein to protect us from disease producing insects. Its research beginning in 1968 resulted in the world’s first plastic banknote which protects against forgery. This basic research was carried out by the CSIRO as part of the public sector. Now required to finance itself, the CSIRO has less scope for basic research (which is expensive and so hard to fund in the market) and has instead to focus on applied research. Which is all well and good, but where are the next basic research breakthroughs to come from? Is this an example of short run gain at the expense of long term loss?

A similar problem arises if we focus on the infrastructure that ‘supports the market’ rather than infrastructure that ‘supports the community’. In her 2017 book ‘The Value of Everything’ Mariana argues that modern economies reward activities that extract value rather than create it and that this must change to ensure a capitalism that works for us all. For those of you who would like a quick insight into her work, I would recommend the article in ‘Wired’(with thanks to @Rohan Fernandez who introduced me to her work via this article). She also has some fascinating TED talks on Youtube.

I have selected just three questions today from Mariana’s 2019 Ted Talk ‘What is economic value and who creates it?’ (which is worth watching, she packs a lot into 18 minutes), but you may add (and answer) other questions that you think relevant to infrastructure decisionmaking. The important thing is that we thing about these things, because if we don’t the choice will not be ours, and may be to our dis-benefit.

- Who are the value creators? Who is not creating value? (e.g. who are just extracting value, or taking it from someone else; and who are actually destroying value?) Who are these people?

- What is the difference between productive and unproductive activity?

- When agriculture was the dominant output, land was considered to be the major ‘source of value’, when we reached the industrial revolution, capital became the dominant source. Now as Mariana shows when we focus on ‘preferences’ the source of value becomes rather vague. How does this impact our infrastructure decisions?

What other questions do you think we need to think about when considering value?

I look forward to hearing your ideas

Have a great weekend!

This is part 3 of the 5 part series by Ruth Wallsgrove and Lou Cripps on Building an Asset Management Team.

This is part 3 of the 5 part series by Ruth Wallsgrove and Lou Cripps on Building an Asset Management Team.

Three: What are the key activities required of an AM team?

Penny Burns identifies three phases (or ‘revolutions’) that it is worth considering when you look at building up AM capabilities.

First, there is ‘Asset Inventory’: ensuring we actually know what assets we manage, where they are, what condition they are in, cost, expected life and their type and model and age.

If you have poor asset information, you have little choice but to start here.

The next stage is what she calls ‘Strategic Asset Management’, in other words ‘Optimization’: using this data, along with our understanding of the assets and asset systems, to begin to optimize at every level. This is where it starts to get interesting.

What does this require from the Asset Management team?

- Co-ordinating the integrated Asset Management Plan

- Leading the implementation of Asset Management, including AM training

- The development and implementation of co-ordinated, whole life asset strategies both at class and system level

- Key role in defining the asset information strategy (but not doing the IT or entering data – which are a waste of AM skills)

- Focus for improved asset decision techniques and models to do the optimizing

Other potential responsibilities of an AM team include helping to define the top level KPIs or Levels of Service. If Asset Management is about aligning asset decisions and plans to the organizational objectives, the first issue for many North American organizations is that the latter aren’t well defined. Sometimes, that inevitably means AM practitioners have to be involved in helping to define them. (And that is explicit for levels of service in ON Reg 588/17.)

It seems inevitable that Asset Management also has to take an active role in developing an overall organizational risk management framework, even if the lead is taken by a specific corporate risk function. This is not just because this is a key requirement in ISO 55000 back to back with ISO 31000; good AM depends on a solid and consistent risk framework across the organization and across all risks. Physical assets can impact on just about every corporate objective, which means they can also contribute to just about every type of risk you have.

Penny believes skilled AM practitioners are key to the next revolution, too: better ‘Infrastructure Decision Making’, by which she means society making better decisions for new infrastructure, especially in a time of change and new technologies such as we face now. Technologists and traditional ‘Planning’ are not experienced in the practicalities of managing complex asset systems, and without this real expertise, we are unlikely to make best use of opportunities.

Note: Talking Infrastructure was specifically created

to explore and develop this third stage, or ‘next revolution’.

Next week we look at what kind of people an AM Team requires.

Photo by Tembela Bohle from Pexels

As we head into another hot January weekend in Australia, here is something to ponder while you drink that cold beer! (or something warmer if you are in the Northern Hemisphere!) Does Infrastructure HAVE value? Does it CREATE value?

What is value?

In 1981, at the height of the Michael Field’s Labor Government’s attempt to bring Tasmania back from the brink of financial catastrophe caused by excessive over borrowing, I was approached by a Minister with a request. He expressed it most diffidently. ‘If you are not too busy, could you tell me what is value?’ I gave him a mini economics tutorial on the subject which he clearly understood, but equally clearly, it did not get at his real problem. For the rest of the week I pondered on this question for it was particularly intriguing that he had prefaced his question by the statement ‘A number of us in the house have been wondering’. Now, one minister asking about value is interesting, but a whole group doing so struck me as quite unusual.

The Source of value?

After a few days, I figured the stimulus for the discussion of value at a time when major cuts were being made to all portfolios, could be that each Minister was simply trying to establish that his department was ‘too valuable’ to have its budget cut. So I wrote a small, humorous, playscript in which various Ministers (of invented portfolios to avoid angst) argued for being the major ‘source of value’ – calling on economic, historic and social support for their case. My Minister was delighted and distributed it to his cabinet colleagues. I had concluded that script by observing that ‘fragrance free soap’ could fetch a higher price than that with fragrance and looked at ways in which each minister could increase value without imposing a cost to the budget simply by removing elements that had ‘negative value’.

Relevant Again

I had not given more thought to this question in the almost 20 years that followed until recently reading Mariana Mazzucato’s work on ‘The Value of Everything’. Just as an understanding of value was critical to that financially strapped Tasmanian Cabinet, so it is also critical to those of us involved in deciding on the shape of future infrastructure and we will look at Mariana’s ideas from this viewpoint in future posts. But, just to get the ‘little grey cells’ working, here are some basic questions to consider.

- What do you understand by value? How do we measure value when considering infrastructure projects?

- Can something that has no price be ‘of value’? For example can private education (with a price) be valuable, yet public education (free) not be? (Some years ago the Head of a major accounting association declared that private schools were assets yet public schools liabilities – purely on the ability to make a cash return. What do you think of this?)

-

Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian

Can something that has a high price not be ‘of value?’ E.g. recently a banana stuck to a wall with a piece of ducktape at Art Basel in Miami Beach was sold at a price of $120K -and not once but three times. It has created a firestorm of comment and brings to the forefront the idea of ‘value’.

- Can cost be a good proxy for value? And if we substitute a more costly (although not necessarily more effective) component, does this really represent an increase in value – as distinct from simply an increase in cost?

- Pharmaceutical companies like to price their products in terms of outcomes -such as the value of better health? Should they be allowed to appropriate all of the beneficial outcomes. Why or Why not?

Do add your comments and we will examine them further next Friday.

Enjoy your weekend!

Photo by Steve Johnson from Pexels

Ruth Wallsgrove and Lou Cripps continue their series on Building an Asset Management Team. Their book is to be published in February. More information to come.

Two: Why you need an AM team

Experience around the world over nearly 30 years strongly suggests the need for a specific, dedicated AM team to be accountable for the implementation and improvement of asset decision, asset risk and long-term optimized asset planning processes.

You can’t just think things better. To improve, there must be action,

and people with responsibility for those actions.

Specifically, ISO 55000 defines AM as the ‘coordinated’ activities of an organization to realize value from its assets. Co-ordination takes real effort, not just a general wish to co-ordinate.

This is no different than other functional teams within your organization where expertise and specialization deliver value. If it is your plan to deliver the AM capabilities, you need to be intentional in adding this competency to your organization.

The likelihood of hitting a target you haven’t specified

or aren’t aiming at is low.

Without a focal point, organizations struggle to do more than isolated improvements, and generally lack a framework or structure to bring together the different activities around assets.

What most will fail to achieve, without at least a small dedicated team, includes:

- The development of whole life strategies for the assets

- Integrated long term asset planning: someone has to do the co-ordination, develop the processes, and build the relationships across functions to bring them together

- Asset risk management beyond safety, general corporate risks, or a high level risk register

- Ownership of the Asset Management system and AM objectives

Take it seriously

It also looks fairly impossible to implement good Asset Management if you have no-one who knows much about it. Rule of thumb: you need at least two people who have been on an Asset Management course to begin.

We might go further and suggest that if there is no-one who is prepared to identify as an Asset Management professional, dedicated to getting themselves and their colleagues developed in Asset Management skills, a company doesn’t really know what to do or how to go about it.

It is easy in this area to be unconsciously incompetent – not even to know what you don’t know.

If no-one in the organization really knows what Asset Management means, they can be sold a line by, a consultant who doesn’t know either. Real examples include organizations who decided Asset Management is an implementation of work management IT, a.k.a. an ‘Enterprise Management System’; or that it equates to reliability-centered maintenance (RCM). Both are very useful tools, but they aren’t a transformation of the business in themselves, and can be expensive, painful and applied wrongly.

Asset Management is about people, relationships, assets and strategies. You need an AM leader that has some knowledge of each. Leadership is a skillset beyond technical knowledge or management proficiencies. So it is worth careful thought about who can deliver this to the organization.

AM is a better way to manage our asset base overall.

For an asset-intensive sector like Public Transit,

that means how we do business overall.

Recent Comments