In discussion the other day we were considering the value of blogs. My companion rated them rather low since it was impossible, he said, to know the credibility of the writer whose opinions were being presented. A natural contrarian, I queried whether opinion, as distinct from fact, really needed to be backed by credibility. Surely, I said, the value of an opinion was to be found in the ideas it generated in the mind of the reader, so that, in a sense, the credibility of the writer was irrelevant. Even an opinion you reject can spark ideas when you consider why you have rejected it. Of course, if the idea was to adopt the opinions of the writer as your own, knowing the writer’s credibility would indeed be important.

In discussion the other day we were considering the value of blogs. My companion rated them rather low since it was impossible, he said, to know the credibility of the writer whose opinions were being presented. A natural contrarian, I queried whether opinion, as distinct from fact, really needed to be backed by credibility. Surely, I said, the value of an opinion was to be found in the ideas it generated in the mind of the reader, so that, in a sense, the credibility of the writer was irrelevant. Even an opinion you reject can spark ideas when you consider why you have rejected it. Of course, if the idea was to adopt the opinions of the writer as your own, knowing the writer’s credibility would indeed be important.

Then again, what constitutes credibility? Academic position? Prominent position? Years of Experience? High IQ? When they started, our leading entrepreneurs today had none of these. But their ideas worked!

Then over the weekend I was listening to Dan Sullivan’s “Pure Genius” and he had something to say on this subject. He spoke of people as being “A” people – those who did not have opinions of their own but read widely and carefully and adopted the opinions of others. “B” people as those who did have their own opinions but did not take responsibility for them and blamed the world for not being what they thought it should be, “C” people, he said, were those who did take responsibility for their opinions and used them to create value and make money for themselves – entrepreneurs. “D” people were those rare people who not only took responsibility for their opinions in order to make money for themselves but also sought to share their knowledge with others.

To my mind a blog is useful in that, in today’s busy world, it presents ideas in small ‘bite-sized’ pieces for further reflection; enables easy feedback (in a way that, e.g., reading a book, doesn’t); can encourage collaborative conversation; it can build up a complex idea in small easy steps with time between posts to provide scope for reflection.

Your take? Pros and Cons of blogs?

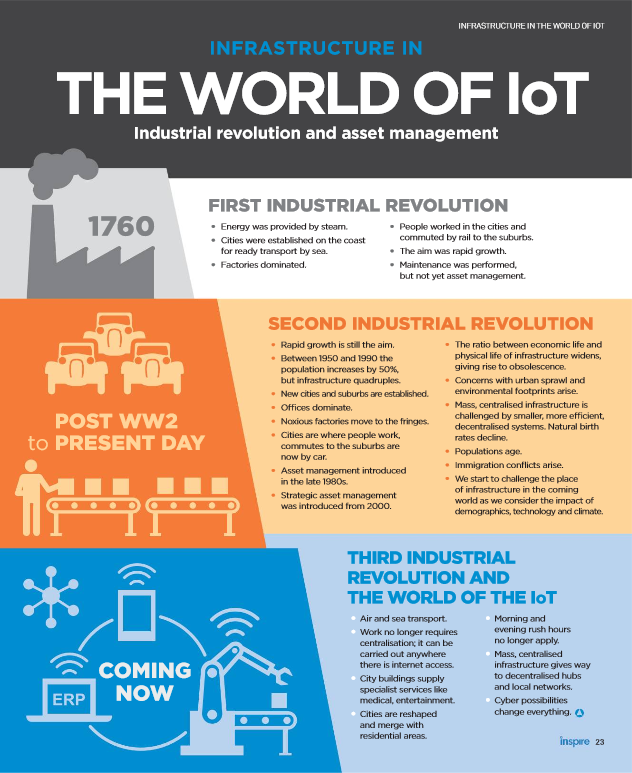

Thanks to the graphics team at IPWEA Inspire for their contribution to our graphic.

The article by Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda “The Third AM Revolution” of which this is part, can be found here

Three words have dominated our thinking, our policy and our practice in infrastructure decision making over the last 30 years – efficiency, sustainability, risk. This is about to change.

Three words have dominated our thinking, our policy and our practice in infrastructure decision making over the last 30 years – efficiency, sustainability, risk. This is about to change.

Efficiency

With large, centralised, and expensive mass infrastructure needed to support public services, ‘efficiency’ was a key concern. But technology is making smaller, distributed, infrastructure, not only cheaper – but in today’s climate of cyber terrorist concerns – also much safer. We are now developing new de-centralised means of provision and our new concern is how safe and effective they are.

EFFECTIVENESS is thus becoming more important than efficiency.

Sustainability

For infrastructure ‘sustainability’ has been interpreted as ensuring long lifespans. We have designed for this and over the last 30 years we have developed tools and management techniques that enable us to manage for asset longevity. This, too, is now changing. With the shift from an ‘asset’ to a ‘service’ focus, functionality and capability have become more important determinants of action than asset condition. This shift is fortunate for it is needed if we are to address the many changes we are now facing – technological, environmental and demographic. At first we thought to ensure sustainability by building in greater flexibility. But change is now too rapid and too unpredictable to make mere flexibility a viable and cost effective strategy.

ADAPTABILITY is the new word. We need to design for, be on the lookout for, and manage for, constant change.

Risk

Risk has been the bedrock tool that we have used in the past to minimise the probability of both cost blow-outs (affecting efficiency) and asset failure (affecting sustainability). Risk management has been a vital and valuable tool. However ‘risk analysis’ implies we know the probability of future possibilities. Today we have to reckon with the truth that the ‘facts’ we used to have faith in, may no longer apply.

UNCERTAINTY is more than risk and requires different tools and thinking.

Effectiveness, Adaptability and Uncertainty.

With these new words comes a requirement for new measures, new tools, new thinking, new management techniques. Life cycle cost models were valuable in helping us achieve efficiency and sustainability and apply our risk analysis. What models, what tools, what measures will help us achieve Effectiveness and Adaptability and cope with Uncertainty?

What new questions do we now need to ask?

For years we have asked ‘what infrastructure should we build?’ Perhaps now we need to ask “What infrastructure should we NOT build?”.

In the last post

In the last post

I suggested that, when it came to new ideas in IDM (Infrastructure Decision Making), the usual sources of new ideas, namely academic research, think tanks and in-house research were limited in their ability to provide workable solutions.

If academics have an incentive to continue research rather than provide answers, who has an incentive to provide answers? If Think Tanks have an incentive to contain their solutions to the subset of possibilities supported by their funders, who has an incentive to look more widely? And if in-house research provides depth but is limited in scaleability, where can we look for answers that can apply over a wider field?

A Suggestion:

I am going to suggest that, curiously enough, it may be the often maligned consulting industry that is, today, most capable of producing the more interesting research outputs when it comes to infrastructure decision making.

There is a growing number of consulting companies that use their in-depth access to many organisations to test and develop ideas in their search for practical applications.

- They have the incentives: increased reputation and customer satisfaction lead to sustained and increased profit.

- They have access to some of the brightest of today’s asset managers, many of whom have, or are in the process, of developing post graduate research theses.

- They have detailed access to information from a large variety of organisational clients.

These are the elite consulting companies. They don’t have to be large, although access to a large client base helps. Small or medium sized consulting companies may achieve the same level of innovation by developing a sharper focus.

Of course, not all consultants necessarily act in this fashion. There will always be those who choose a ‘cookie cutter’ approach and try to fit your problem into an already conceived solution. But what you will see in the better, more innovative, firms are that they apply themselves to thoroughly developing an idea; they stick with it over the time it takes to bring it to fruition (often years); and they expose their ideas to others (in conference presentations and in papers on their websites).

Nearly always the effort will revolve around one or a few talented and motivated individuals. For this reason, it pays to follow the activities of such individuals in consulting organisations that you are thinking to use. LinkedIn is a good source for this.

Other Suggestions?

Where are new ideas in infrastructure decision making to come from?

Academia?

One might suppose so. Yet how many times do you get to the end of a promising piece of research only to find nothing that can be adopted for practical use, only an indication of potential and a recommendation for further research? Frustrating, yes, but unfortunately this is an academic necessity. In our ‘publish or perish’ world, where one published paper is used to generate the research funding for the next, producing a workable solution that can be adopted by practitioners is an academic ‘dead end’, and nowhere near as academically useful as papers that generate problems for further research.

One might suppose so. Yet how many times do you get to the end of a promising piece of research only to find nothing that can be adopted for practical use, only an indication of potential and a recommendation for further research? Frustrating, yes, but unfortunately this is an academic necessity. In our ‘publish or perish’ world, where one published paper is used to generate the research funding for the next, producing a workable solution that can be adopted by practitioners is an academic ‘dead end’, and nowhere near as academically useful as papers that generate problems for further research.

Think Tanks? Federal Inquiries?

If we cannot look to academia for useable research – that is research ideas that can be applied in practice – where else can we look? There are, of course, think tanks or public inquiries such as the Productivity Commission. These are usually very well funded and employ some of the brightest individuals. However, both the topics and approach chosen will of necessity be determined by the funding organisation or the incumbent government and may not be unbiased.

Public Service and Public Policy White Papers?

Once, excellent research papers were produced by the Public Service. In the 1970s and 1980s, the ability to produce well written and researched ‘white papers’ was a highly prized skill. However politicisation of the Service and the unfortunate elevation of the craft of ‘spin’, have taken their toll. There are still pockets of excellence in the Service, but, with downsizing, there are few instances of good research written to a rigorous standard and subjected to the test of knowledgeable peers.

Asset Owners, Managers, Decision Makers themselves?

What about in-house research by asset owners? This can often produce some very well researched and well written case studies. The difficulty with adopting the ideas produced, however, is that they are heavily dependent on the organisation itself – its prior development, its general culture, leadership and organisational knowledge. Such research produces interesting case studies but presents problems of scaleability.

So what are we left with? How do we progress?

Desert island

An engineer, a physicist and an economist are shipwrecked on a desert island. All they have is a tin of baked beans but how are they to open it? The engineer considers hitting it with a rock, the physicist suggests heating it over a fire. The economist, however, smiles and says: ‘Let us assume we have a tin opener’.

I am an economist, so assumptions come very easily to me, I know how useful they can be. However, I have also learnt to be wary of their uncritical use – and there is an awful lot of uncritical use around today. Why is this? To understand, we need to ask

What are assumptions and where do they come from?

I once assigned a problem to an engineer working for me. I told him that he could solve the problem any way he liked, just so long as he documented all the assumptions that he made. After a couple of weeks, he supplied his solution. “And where are your assumptions?” I asked. “Oh, I didn’t make any!” he replied.

I pointed to a number of the assumptions in his solution and said “What about this – and this?” “They are not assumptions” he repied indignantly, “they are the results of my years of experience!”

And that, in a nutshell, is why assumptions are so valuable – and, at the same time, so dangerous. Our years of experience enables us to take shortcuts to get the work done but only when doing things the way we always have. When change comes, doing – and thinking – ‘the way we always have’, stops being a shortcut, and becomes a fast track to disaster.

When change comes, we need to rethink our assumptions but years of conditioning makes this very hard, if not impossible.

To succeed in a changing world, we must learn to question assumptions.

Question: But how?

Saw this book title “What would you do if you knew you couldn’t fail?”. My instinctive response was “Nothing! What would be the point?” I am not suggesting we should court failure, but we definitely shouldn’t be afraid of it. Of course, we all want things to go ‘according to plan’. But when was the last time you actually learnt anything when it did? Without the possibility of failure, can you really succeed?

Saw this book title “What would you do if you knew you couldn’t fail?”. My instinctive response was “Nothing! What would be the point?” I am not suggesting we should court failure, but we definitely shouldn’t be afraid of it. Of course, we all want things to go ‘according to plan’. But when was the last time you actually learnt anything when it did? Without the possibility of failure, can you really succeed?

‘Disruptive change’ is today’s mantra. Along with rapidly increasing technological change, the economy has also seen a large increase in the number of ‘solo entrepreneurs’. This is not coincidence. The latter, no doubt, has a lot to do with downsizing in large companies, and by government, but it also reflects a greater willingness to assume risk, especially by the young. They interpret risk not as ‘a risk of failure’ but rather as ‘a risk of great success’. And the world is benefitting by it.

However, can solo entrepreneurs, or at least small businesses, make a difference in infrastructure? Is this not a game in which only the mega-large or mega-rich can play? For large scale production this is probably still true. However for advice on policy, assessment of project proposals, improving decision or production flows, and many other aspects, small is definitely beautiful – it is nimble, can move quickly, is not bound by the need to protect past decisions. And technology is now making large scale production (large, centralised, physical infrastructure) no longer the obvious ‘go-to’. So whether you are an organisation looking for an infrastructure solution or a solo entrepreneur in this space; small, customisable, and niche is the way things are going.

PS. If you are a solo entrepreneur in this space, you may enjoy a blog and podcast which I have recently discovered. It is “Flying Solo” – everything you want to know about being a solo entrepreneur. Its tag line is “work for yourself – not by yourself”. I am enjoying it so have a look or a listen and tell me what you think.

Is it time?

Is it time?

It used to be the case that we elected people to govern us and then trusted them to get on with the job – while we got on with ours! But the world is changing. For one thing, we are getting smarter! According to the Flynn Effect, IQ scores are increasing by about 3% every decade. We are also more educated and continue to learn. In Australia, more graduate and more continue to study throughout life (especially women!). Access to digital technology also means that we can be more aware.

The upshot is that many are no longer prepared to let others make decisions for them. They want to be more involved in decision making. Sure, smart phones can be used to report light outages and potholes, and individual data can be collected for community improvement. But is it enough?

According to the Economic Intelligence Unit in their report ‘Empowering Cities’. in a study of 12 cities around the world, the majority of citizens want to contribute to decision making – especially in healthcare, education, pollution reduction, environmental sustainability, and waste collection, treatment and recycling – but they don’t know how.

These are areas in which citizens – as users of the services – could have much to contribute. These are also areas in which infrastructure features heavily – and where, at the moment, the views of infrastructure providers prevail over the views of users. Would greater citizen discussion of infrastructure issues lead to improved outcomes?

Talking Infrastructure believes so. What do you think?

“I love ‘Talking Infrastructure’ – you ask questions that I have no answers to”. (recent email from an experienced asset management trainer)

“I love ‘Talking Infrastructure’ – you ask questions that I have no answers to”. (recent email from an experienced asset management trainer)

Questions for which there are answers are ideal for training courses, manuals, and instructions. Asset management, where the task is to how to choose those asset activities that best achieve the organisation’s objectives, is now, after thirty years of development, at this stage. Not everyone may know the answers but an increasing number are learning the ‘how to’ from those who do. The procedures themselves may change, a little: they may be clarified, refined, improved, but they no longer need be ‘discovered’ for that has already been done. The reason I can say this with a certain amount of confidence is that the task of ‘achieving objectives’ is a technical issue, one of optimisation under constraints.

Choosing those objectives, however, is a different matter. Clearly communicating the chosen objectives is yet another! Here we are dealing with values, and with complexity. We are in the realm of ‘wicked problems’. According to Wikipedia. “A wicked problem is a problem that is difficult or impossible to solve because of incomplete, contradictory, and changing requirements that are often difficult to recognize. The use of the term “wicked” here has come to denote resistance to resolution, rather than evil”. Incomplete, contradictory and changing requirements, well describes the problem facing those who need to set infrastructure objectives today. And, yes, they are also difficult to recognise.

How could it be otherwise where, for infrastructure decisions, the need is to plan ten, twenty, or more years into an unknowable future; where we need to juggle the needs of present v future generations, of present v. future technology, of present v. future needs, demands, values and expectations. What do we favour – economic, social or environmental outcomes? With due respect to the ‘triple bottom line’ which implies that all can be accommodated, the truth is that all conflict.

We can act as if this complexity does not exist and ‘muddle through’, a long established British tradition.

But perhaps the complexity is ‘difficult to recognise’ because we are not examining it?

‘Talking Infrastructure’ is designed to explore these difficult, complex, issues, so that we become more aware, more able to see a path through the complexity, and to debate them so that we are more able to explain whatever path we have chosen to others.

Your view?

A time for gratitude. The Talking Infrastructure Blog started on July 29 and since then, with the help of Mark Neaseby, Gregory Punshon, Jeff Roorda and Geoff Webb (thanks guys!) we have uploaded 46 posts and attracted 80 comments.

A time for gratitude. The Talking Infrastructure Blog started on July 29 and since then, with the help of Mark Neaseby, Gregory Punshon, Jeff Roorda and Geoff Webb (thanks guys!) we have uploaded 46 posts and attracted 80 comments.

Our thanks to all readers for their presence here and I hope that it has got you thinking more about infrastructure decision making. And for those special readers who submit comments, let me say that I regard each and every one of them as a present and I take great delight in unwrapping them and discovering the truths they reveal. It is a curiosity of the complex world of infrastructure decision making that we can all much appreciate the arguments of others even whilst arguing against!

And if you should choose to use the holiday break for some practical or philosophical reflection on IDM issues -know that the web is always open!

Recent Comments