Join us at the Harbour View Hotel in the Rocks and help celebrate with finger food and drinks – plus Penny and Jeff on what we have learnt from the last 40 years to help us meet the challenges of the next 40.

Many thanks to Richard Edwards, Lynn Furniss and Matt Miles of AMCL

Penny Burns and Talking Infrastructure will be on the move in April to celebrate 40 years of Asset Management, and look forward to the next 40.

Adelaide April 15 & 16, Penny and Ruth will be celebrating at AM Peak.

Brisbane events April 17-19

Sydney April 24, venue TBC: Asset Valuation in a time of Climate Crisis. Including Jeff Roorda on how Blue Mountains City Council is taking a radically new approach, as well as Penny on how we must rethink our AMP modelling.

Melbourne April 30, IPWC. Penny speaking on the opening morning of IPWEA conference

Wellington May 4-6, events to be announced

Let us know if you are interested in meeting up in any of these cities.

See you in April! #AMis40

Someone I work with in the UK nuclear industry asks in despair, how come project engineers don’t feel that the whole point of building something is for it to operate? In other words, that construction projects only exist to create something that will be used to deliver products and services.

Why aren’t they interested in the long-term use that comes after construction?

If it really is all about use, they really need to consider what is required to use the asset. They should be interested!

This isn’t just to focus on what service we need to deliver. The asset has no point unless it delivers a service that is needed. Even project engineers can get that.

What we continue to struggle with is getting asset construction engineers and project managers to consider what is needed in order to use it successfully. And this includes providing as-built data – what assets are there to operate – and thinking ahead on operating strategy, and maintenance schedules. It’s designing and building with the operations and maintenance in mind. Designing for operability and maintainability.

In infrastructure, the asset ‘users’ are often not the customers, who may never touch or even see the assets. The people who use the assets are the operators; the people who touch the assets, maintenance.

An engineering design goes through many hands before it impacts on the customer – and if those hands in between are hamstrung by designs that are poor to operate, hard to maintain, and by the incomplete thinking that ‘throws the assets over the wall’ at operations (as we used to say in the UK) without adequate information – what is the point, really?

I believe there may be something called project time, where there is no ‘after’. No ‘and then what?’ – just onto the next shiny thing to build.

Thanks again to Bill Wallsgrove

Human beings may not naturally be good at thinking about the future.

One thought is that, just like with charity appeals for current disasters, we should focus on an individual. Think ourselves into the shoes of some one as they experience the future.

It could be ourselves, a grandchild (if we have one), a ‘descendant’ – or anyone we can picture.

A startling powerful example of this appears in the first chapter of Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future, published in 2020. The author specialises in thoughtful, ‘realistic’ depictions of the future, for example in colonising Mars.

The Ministry for the Future starts by describing the experience of one Western man in a climate catastrophe, when twenty million people in northern India die in a heat wave. Many millions in a faraway country in the future: a newspaper headline. And ‘Frank May’, who works in a clinic near Lucknow, who nearly poaches to death in a lake full of people, where the water is above the temperature of blood.

I could not get the image of him out of my head for a lot longer than a headline.

I realised when watching the final episode of Planet Earth 3 last month that the image of Frank May was so vivid that it felt it was happening right now. It was not hypothetical, despite being fiction.

We may overdo the image of threats to a panda or polar bear or orangutan, to be invited to imagine a world without them. Just like we stop reacting to doe-eyed young children in charity ads. But I suspect we simply need this emotional connection.

Maybe like the Japanese traditionally put on the garment of a descendant, to feel how they will perceive the results of what we are doing now. We too could do this, to really feel it when we make a decision now about their infrastructure in fifty years’ time.

A technique to consider next time we are involved in long term asset decisions?

My colleague Todd Shepherd and I had a brainwave* last year to restructure how we teach Asset Management – not as a line that starts with investigating capital needs, the conventional beginning of the asset life cycle, but from where we are now. That is, right in the middle of maintenance. We are always deep in maintenance needs.

It makes more sense of the history of AM, straight off. It was not people writing business cases, or design engineers, who realised the urgent need for something different. It was maintenance, post World War 2, and then Penny Burns and the problem of unfunded replacements and renewals in the 1980s.

If Asset Management has waves, we might suggest what Wave Minus 1 was. Wave Minus 1 was hero engineers, from the Industrial Revolution on, building heroic infrastructure – Bazalgette and London sewers, Brooklyn Bridge. Sewers and bridges are both good things. But they are not quite such good things if they leak or fall down because they are not maintained or renewed.

With infrastructure, it is not enough to start; you have to see it through.

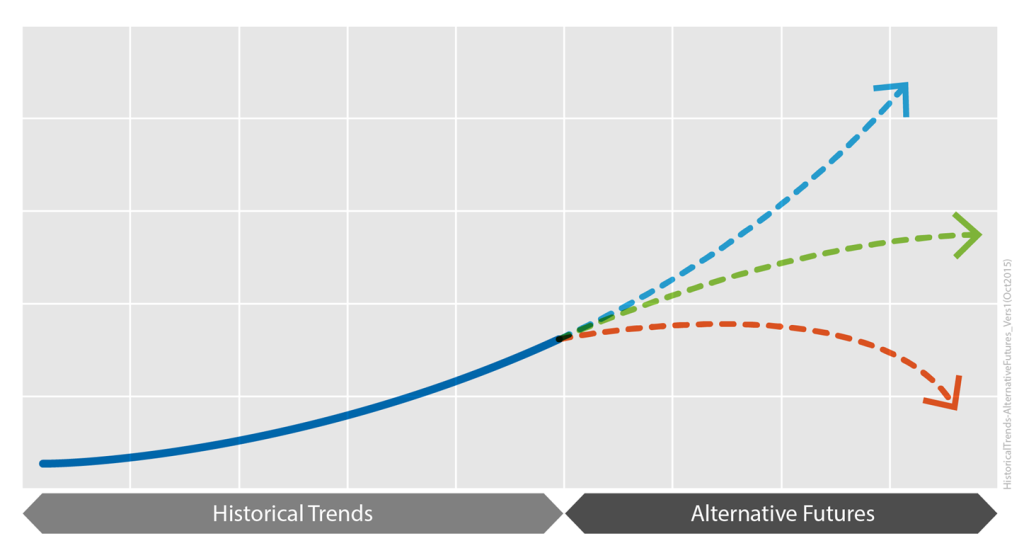

Penny used life cycle models to understand the extent of renewals, and increasingly I don’t feel anyone is really doing Asset Management if they do not use such models. Of course it is called life cycle for a reason. There isn’t an end, only another cycle.

But now I fear that starting at the beginning of one lifecycle in our teaching still makes it sound as though it is the creation of infrastructure that’s the important thing. We have not really got the cycle bit across enough, at least to the average engineer we teach. What comes after construction is still a vague future state, that is someone else’s problem.

And, not at all coincidentally, that’s also the point of the circular economy concept. There is no meaningful product end, and we are right in the middle of the mess we already built.

It is not a straight line into the future, where we set assets in motion and let them go. Longer term thinking, long-termism, has to think in cycles.

*Almost certainly it was Todd’s brainwave, which I managed to catch up with.

Thanks to my brother Bill Wallsgrove

Board member Lou Cripps and his team at RTD are great Asset Management practitioners – and that is largely because of their attitude to time.

For example, the team prepares carefully for meetings with key stakeholders, not just the CEO but engineers, IT, maintenance, HR. They think carefully about what they want to effect through the meeting – their objectives – and then project forward what the possible response/s of the others will be, based on their previous interactions. They can then work on what will most connect and make a win:win outcome likely.

Lou’s team also makes full use of red-teaming and pre-mortems, to imagine what could go wrong with an initiative so they can prepare not to go there. Risk assessments and risk plans, essentially, but exploiting the human ability to project forward and then ‘look back’ in our minds. (“Imagine it’s six months’ time and we are doing a post-mortem on what went wrong.”)

Lou refers often to ‘future me’ and ‘future us’: that is, stepping in the shoes of himself in a year or ten years’ time. This is not just to feel how fed up he might be then about what he failed to do now, but also to consider what future him would care about more widely. It is empathy with a future self. And it does not even need to be yourself. What about someone in the community in a hundred years?

This is good Asset Management for infrastructure, in particular, as infrastructure decisions we make now should always be assumed to have lasting implications. The assets we build now may still be in use in a hundred years. And the things we don’t build because we’re building something else. The lost opportunities, and future debts. What we fail to maintain, so will have to be built again…

Lou’s team last year relentlessly analysed the data to work out the likely costs – the total costs, now and into the future – for a proposed project to buy more electric buses. They worked out that this particular set-up would cost their transit agency approximately $2 a mile extra on every electric route for the next 50 years. It wouldn’t even save on carbon, because the electricity supply proposed was fossil fuel burning generation. (It was not a good proposal, and the Board duly turned it down thanks to their analysis.)

To build and not think ahead is a dereliction of duty. Principle number one for an Asset Manager: always ask, “And then what?”

Making full use of the past, in order to think ourselves into the future.

How do you this in your team?

In 2024, Asset Management turns forty.

One key question for me this year as an Asset Management practitioner is time itself, and how we act with the future in mind.

The innovation of Asset Management is very largely about time. Penny Burns created AM to look forward in time and consciously choose whether we needed to renew like-for-like, or should manage our assets differently in future.

Forty years ago, we were not thinking about climate catastrophe, and we were only just at the start of the IT revolution. (I had only just seen my first PC, and the world wide web, smart phones and terabytes of data storage for $50 were barely pipedreams.)

But the question of longer-term thinking has in some ways gone backwards in our societies since then, not forwards.

The vast majority of infrastructure organisations still only have very short term asset plans, and almost no asset strategy. More have, must have, 3- or 5-year plans now, thanks to AM as much as anything. But the 15 to 20 years plus strategic view that Penny proposed is still a challenge.

And shockingly few agencies even use life cycle modelling to project the very basic realities about the timings for replacements, let alone a mindset of always asking ‘And then what?’ of our day to day and year to year asset decisions.

I fear as a community we are still underskilled, underprepared for the future: for embracing uncertainty and identifying with the future.

And so, as we celebrate, look back and learn from the last 40 years, Talking Infrastructure plans to act like the future matters.

Starting with a time series of blogs to ring in the New Year. Your contributions most welcome!

In April 2024, it will be 40 years since Penny Burns started the whole thing. Talking Infrastructure plans to party like it’s 2024, all year.

2024 also marks milestones for the Global Forum for Maintenance and Asset Management (update of the AM Landscape), ISO (10 years since ISO 55000), and the Institute of Asset Management (30 years since it was founded): there will be a lot happening.

The need for more considered decision making for our future infrastructure has only grown and become more urgent. Asset Managers everywhere know this. Our 40 year celebration will be an opportunity to take this message not only to managers of infrastructure but also to those who decide, design, construct, fund and vote for our infrastructure.

Like infrastructure itself, our purpose is to support the wider community. There is a lot of satisfaction to be had in this and we invite you to join us, and enjoy it too. What area of Asset Management and decision making particularly interests you?

We are looking to develop a circle of advisors, who, through their interests and work, can have the fun of keeping Talking infrastructure up to date with current issues, and setting its future directions.

Your ideas for celebrating our 40th are also needed and much welcomed. This will include events across Australia in April, and presence at AM conferences and articles wherever and whenever we can.

What did we learn in the last forty years? Where do we need to go in the next 40 years?

© https://www.dreamstime.com/ image120059878

I love a friendly alien. Some of us – possibly the less military minded – have long preferred stories of good contact experiences, from ET and Close Encounters of the Third Kind to Arrivals. Indeed, the grandmammy of them all, The Day the Earth Stood Still, which is about the shortcomings of militarism.

There’s a new generation of sci-fi with what can only be described as positively cuddly species from other planets. The close encounter in A Half-Built Garden, by Ruthanna Emrys, echoes The Day the Earth Stood Still in that the aliens have come to save humanity from itself. But the ‘dandelion networks’ are already saving the planet through direct democracy based around watersheds, to them the natural way to organise.

And it could not be more cuddly: the first human to meet the aliens is woken by water pollution alarms in the Chesapeake in the middle of the night, and hurries out to check what is happening taking her baby with her. Turns out the aliens don’t trust anyone who would not bring their babies to a key negotiation.

The principle the dandelion networks use in decision-making about infrastructure and other technology is: will what we are building be at least as benign as a cherry tree? With evident, multiple benefits and few costs, and a net positive impact on the environment?*

If not, don’t build it.

Is there anything we are building today that would pass the cherry tree challenge?

*Ruthanna borrowed the metaphor from Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things by William McDonagh and Michael Braungart, 2009.

Recent Comments