We are about supporting AM Leaders!

Here’s the situation we face:

We are moving into a “perfect storm” where our natural and built assets move into states of uncertainty and instability. We must rapidly build an understanding of the integration between our ecology and built infrastructure because rapid changes will increasingly challenge or capacity to foresee and manage risks. We are already seeing the initial evidence or these risks in major fire and flood events and likely pandemic events.

Growth boom infrastructure is approaching end of life, ageing population requires infrastructure realignment, climate, environment and virus risk changes start to move from debated possibility to clear and present dangers. Technology is the wild card with the potential to provide new solutions or exacerbate existing problems. Where we allocate our resources is more important than ever before.

The decisions made by this generation will determine the quality of life of future generations. A future that could be bleak and fearful or exciting, prosperous and filled with hope. Our current decision-making framework and decision support processes, systems and assumptions need rapid overhaul to support our current leaders guide us to the future we want and the following generations deserve. We can avoid reacting to preventable or manageable disasters by developing integrated rather than fragmented strategic plans.

What do we want for our future?

Talking Infrastructure’s Vision is a world in which decision makers understand and care about the cumulative consequences of their decisions and their constituencies understand the trade-offs involved in those decisions.

What do we have to stop doing?

We need to stop thinking of ‘infrastructure’ as a panacea for all economic ills, but rather to consider individual infrastructure projects and their individual contributions to general wellbeing – economic, social, and environmental. What questions do we need to ask of all projects to make sure that we are ‘future friendly’? What do we need to know about the relationship between future change and infrastructure? What changes do we need to make to current decision processes to achieve this goal? Could these resources be better allocated to prepare for future foreseeable risks.

We want to avoid infrastructure waste. Stranded assets are assets that are now obsolete or non-performing and recorded in corporate books as a loss of profit. Current estimates vary but run into the many trillions of dollars. Climate, technological and demographic changes all contribute to this problem. But so do we – when we construct infrastructure better suited for the 20th than the 21st century. Every year we use up valuable resources and add to environmental damage and often social damage, constructing long-living assets destined to end on the stranded assets scrap pile. Resources that could be used to mitigate more urgent foreseeable risks.

We believe we can do better

In the past, governments have tended to see infrastructure as an expenditure ‘blob’ – useful for soaking up unused corporate savings to ‘kickstart’ the economy or as a generic ‘source of jobs’. These are the attitudes that have got us where we are now. We believe that if we focus on ‘future friendly’ projects, that takes future change into account and specifically designs for it, we can avoid unnecessary waste and manage future risks.

This requires us not to think of ‘infrastructure’ as a panacea for all economic ills, but rather to consider individual projects and their individual contributions to general wellbeing – economic, social, and environmental. What questions do we need to ask of all projects to make sure that we are ‘future friendly’? What do we need to know about the relationship between future change and infrastructure? What changes do we need to make to current decision processes to achieve this goal?

This is what Talking Infrastructure is about!

Do you also believe we can do better?

JOIN TALKING INFRASTRUCTURE

to keep up with latest thinking and doing and join us in our work towards wiser infrastructure decision making,

go to top of the right hand column.

It’s free and you will be part of a growing number of professionals from all disciplines: planners, strategic asset managers, financial specialists, environmental scientists, economists, sociologists, administrators and many others who share the realisation that to really benefit from the many changes that now surround us, all decisions need to undertand the past, act in the present ,and be open to the futures now emerging, so

Get Involved! Members receive our monthly newsletter containing brief synopses of what we have posted during the month and opportunities for you to share your knowledge and ideas with others.

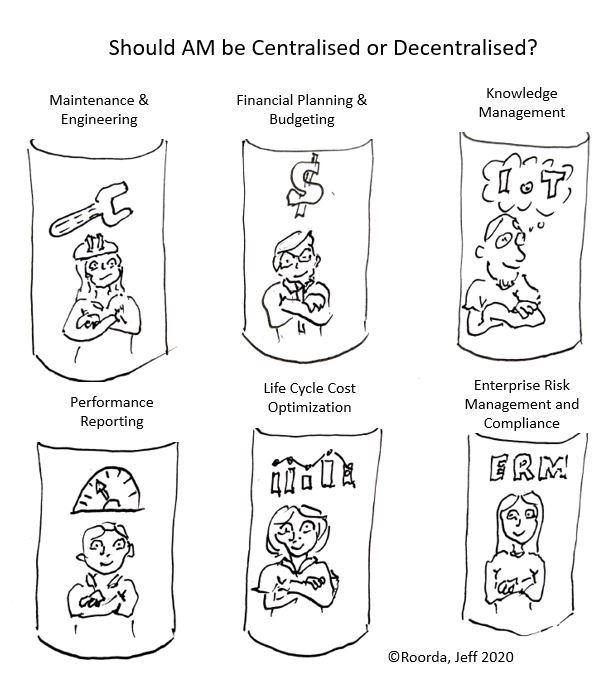

Whether asset management should be centralised or decentralised has been asked since the beginning of Asset Management (AM) as a structured activity. Many organisations have cycled through these structures, some several times. We have seen both models succeed and struggle. Before considering which organizational structure is best, we can learn from what has worked in the past.

The common primary success factors are a good asset management team leader with top management (ISO, 2014) support and commitment over the long term. Without both of these in place, fragmentation into silo’s of finance, maintenance, construction, compliance and knowledge management is the most common result. Often these silos are in adversarial competition for resources with short term horizon of less than 5 years.

The key focus of the ISO 55000 series and IIMM is the role of the AM Leader and the interaction with “top management”. Leadership is not the same as management although they are complementary and often overlap. (IIMM, 2015). A secondary, but essential success factor is at least 2 people who are proficient and have experience in asset management. (Wallsgrove, 2020)

With these success factors in place, that is, top management commitment, a good AM leader, and at least 2 people with AM knowledge and understanding, a centralised structure has a lower likelihood of fragmentation into the AM silos mentioned above.

Good communication skills are the essential attributes of a leader to communicate throughout the organization how the organizational objectives are to be converted into asset management objectives (ISO 55000 2014, 3.3.2). This manages the primary risk of fragmentation of asset management into competing silos with fragmented or inadequate skills.

Both international source documents, ISO 55000 series and IIMM are consistent in defining the roles and responsibilities of asset management in an asset intensive organization as much more than maintenance management.

References

IIMM, I. I. (2015). IIMM International Infrastructure Management Manual.Sydney: IPWEA.

ISO. (2014). ISO55000.Geneva: ISO.

Wallsgrove, R. and Cripps, L. (2020). Building an Asset Management Team .Amazon .

AMQ International’s ‘Strategic Asset Management’, ed: Dr PennyBurns, Issues 270, 298, 371

Footnotes

1. SAM 270 looks at different structures, all of which were adopted successively by an Australian Rail Company when they discovered the problems with the one they were currently using. The whole issue looks at organisational structure.

2. SAM 298 pp 3-5 ‘Four models of AM organisation within councils’

3. SAM 321 ‘A Perfect AM Organisation?’ pp 1-3

4. Roorda (JRA) was the Asset Management Consultant for BART from 2012 – 2015 and established a successful asset management programme for BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) with John McCormick and Frank Ruffa. AM Council News and Asset Management Implementation and Integration Frank Ruffa

Sometimes you ask a question and the answer is unexpected but once read, so completely obvious, you feel an idiot for not seeing it in the first place. Read this exchange on bushfires (and value) between Jeff Roorda and me – but mostly Jeff.

Jeff:

The devastating fires that have blighted Australia in 2020 have now burnt through 18.6 million hectares of land. The fires had a total perimeter of 19,235 kilometres. That’s the equivalent distance of Sydney to Perth four times over and further than Sydney Australia to Los Angeles USA.

An estimated 1 Billion animals were killed, and entire species or plants and animals may have been wiped out. 33 people died and 2,779 homes were lost.

The cost to fight large fires is very high and growing with questions about the effectiveness of reactive strategies. We have avoided putting a value on air, fire, water and earth because it doesn’t neatly fit into our built infrastructure silos.

A large fire shows not only the connections of our artificial silos, but is instructive in a better understanding of value, cost, benefit and risk. These are the inputs to asset management plans. Decisions can then be based on scenarios based on evidence, expertise and experience to come to a wisdom decision for future generations.

We understand cost and cost and value are connected. The cost to react to crisis is high and growing but cost should be based on an asset management plan that has benefit, cost, risk and value of decision scenario options.

Penny:

Fires do not confine themselves within council boundaries, or even State boundaries and this was amply demonstrated in our recent (indeed still current) fires. Asset management plans are necessary but they are, sadly, not sufficient. How do we go further?

Jeff:

If any future event is identified then there are options to mitigate that event. Examples are a large fire, reliable energy or water or infrastructure congestion or under utilisation. Not making a decision or not having an evidence based asset management plan with possible scenarios is actually a decision to run to fail.

This often happens because we think we can’t reliably measure value. But when we get to the point of run to fail we can measure cost. In 2017, the NSW Government invested $38 million over four years for three Large Air Tankers to be used in firefighting efforts. In December 2019, the Federal Government announced $11 million on top of the annual $15 million. Add to this State and Local Government Costs and the opportunity cost of over 72,000 members just in NSW.

So there is a connection between cost and the value we put on something. Concepts such as deprival value and service potential become useful. Cost is a proxy for the value of what we lost, human lives, houses, businesses, over 1 Billion animals died and some flora and fauna may be extinct. A better concept of value is essential to making long term decisions for future generations.

Jeff Roorda continues the story he began with Motorways and Steam Engines (Mar 27)

In part 1 we introduced the difference between physical life and economic life.

In part 1 we introduced the difference between physical life and economic life.

Part 2 talks about certainty bias, that is, we pretend to be certain about the future even though this is an irrational and emotional response. The feature photo shows the I-35W Mississippi River bridge collapse (officially known as Bridge 9340). An eight-lane, steel truss arch bridge that carried Interstate 35W across the Saint Anthony Falls of the Mississippi River in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA collapsed in 2007, killing 13 people and injuring 145. The bridge had been reported structurally deficient on 3 occasions before the failure and ultimately failed because it was structurally deficient. The design in the 1960’s had not anticipated the progressively higher loads compounded by the heavy resurfacing equipment on the bridge at the time of failure. There was no scenario I could find that explained clearly enough for any reasonable non-technical person to understand, the likelihood and consequence of failure and the uncertainty of the safety of the bridge. After the failure, the courts found joint liability between the initial 1960’s designers and subsequent parties involved in managing the assets. The allocation of blame and acceptance of wrongdoing was highly uncertain, but lawsuits were settled in excess of US $61M. The strength and life of the bridge was uncertain and this was reported in technical reports but every person that drove over the bridge and every decision maker with the power to close the bridge had the illusion of certainty that the bridge was safe and would not fail.

As asset managers, our estimates of asset life have critical consequences but are uncertain. We estimate and report how long an asset will last before it fails, is renewed, upgraded or abandoned. This then determines public safety, depreciation, life cycle cost and our future allocation of resources. Whether we decide to use physical or economic life, we still are making a prediction of the future, something we should be uncomfortable about when we really think about it. None of us knows what will happen tomorrow, much less in 10 or more years. We prefer the illusion of certainty, or expressed another way, we have uncertainty avoidance. Uncertainty avoidance comes from our intolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity. Robert Burton, the former chief of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco-Mt. Zion hospital wrote a book in 2008, “On Being Certain”, in which he explored the neuroscience behind the feeling of certainty, or why we are so convinced we’re right even when we’re wrong. There is a growing body of research confirming this phenomenon. So then, what do we do about asset life? We prefer the comfortable feeling of certainty because of the discomfort of ambiguity and uncertainty.

Today’s post is by Jeff Roorda, Technology One, and Deputy Chair of Talking Infrastructure.

Is using condition to determine life a fundamental error in asset registers?

Part 1

How long does an asset last? The answer determines life cycle cost, depreciation and infrastructure planning.

Asset registers estimate useful life for every asset but which life do we use? The physical life or the economic life? Yes these are different, and often materially different. I recently was working in Queenstown NZ with Queenstown-Lakes District Council. After work, I boarded the steamer TSS Earnslaw that had been carrying passengers on lake Wakatipu since 1912, and its steam engine is still powered by coal. The Earnslaw and many steam powered transport assets around the world still have many years of remaining physical life after over 100 years of operation.

So why did we stop using steam for transportation ? Was it because the assets reached their physical life?

In hindsight we all know the answer. Because steam power is dirty and technology made steam power obsolete. OK then, so the economic life was determined by function and capacity, not by physical condition. Even though steam powered assets had many years of physical life remaining, they became obsolete relatively quickly, far more quickly than most people managing the assets predicted. How much of the infrastructure we are building right now will be obsolete well before physical life is reached? So why do we focus on the measurement of physical life using condition instead of function and capacity? The pace of change could be faster now than in the 1940’s and 1950’s when transport shifted from steam to the internal combustion engine which created the infrastructure networks we now manage.

Think about what we are building now and drivers for change.

Infrastructure based on continuing the past where everyone has to travel to the office at the same time creating peak transport loads using internal combustion engines with one person per car does not seem to be a likely future with changes in communications and energy technologies.

Recent Comments