What will happen next?

In the last post I suggested that we shouldn’t be shy about questioning assumptions. But what? ALL assumptions?

Assumptions serve a purpose, otherwise they wouldn’t have lasted so long. They enable us to take shortcuts. Suppose I assume it is going to be sunny and don’t take a coat when I walk to the neighbourhood shops and get caught in a downpour. What are the consequences? I get wet and I am uncomfortable. But it doesn’t last long, and I am the only one affected. True, it would have taken but a moment or so to check my iPhone, so I probably also feel an idiot. But that’s it. Cost is small, temporary, and impact is limited.

Now consider an infrastructure decision where:

- the costs are large,

- the consequences last a long time, and

- they impact many people.

So when the consequences are low, by all means save yourself the effort if you wish, but if they are high – and particularly when the consequences are to be borne by others – we owe it to them to check, to question, to verify.

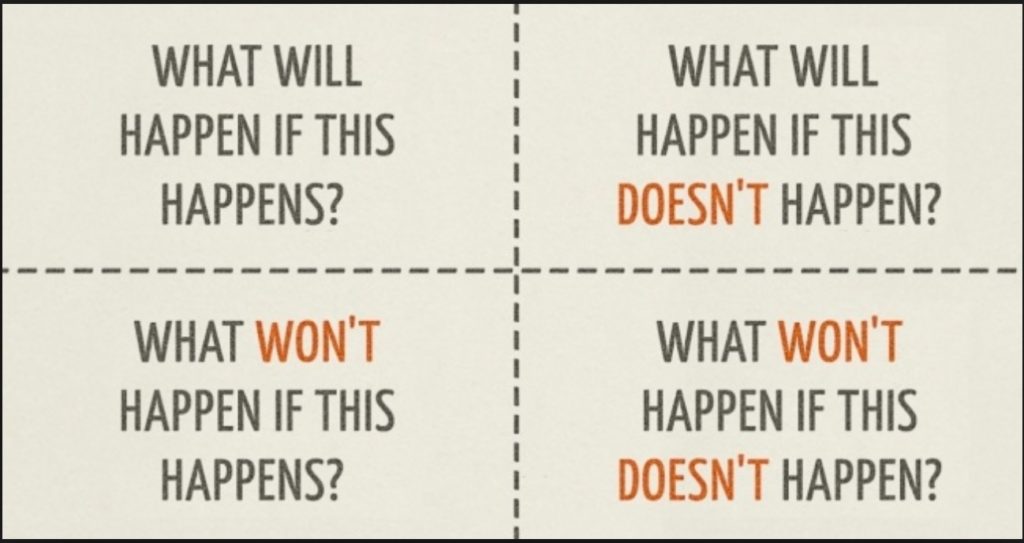

The DESCARTES SQUARE is a useful tool to ensure that ALL consequences are considered:

Desert island

An engineer, a physicist and an economist are shipwrecked on a desert island. All they have is a tin of baked beans but how are they to open it? The engineer considers hitting it with a rock, the physicist suggests heating it over a fire. The economist, however, smiles and says: ‘Let us assume we have a tin opener’.

I am an economist, so assumptions come very easily to me, I know how useful they can be. However, I have also learnt to be wary of their uncritical use – and there is an awful lot of uncritical use around today. Why is this? To understand, we need to ask

What are assumptions and where do they come from?

I once assigned a problem to an engineer working for me. I told him that he could solve the problem any way he liked, just so long as he documented all the assumptions that he made. After a couple of weeks, he supplied his solution. “And where are your assumptions?” I asked. “Oh, I didn’t make any!” he replied.

I pointed to a number of the assumptions in his solution and said “What about this – and this?” “They are not assumptions” he repied indignantly, “they are the results of my years of experience!”

And that, in a nutshell, is why assumptions are so valuable – and, at the same time, so dangerous. Our years of experience enables us to take shortcuts to get the work done but only when doing things the way we always have. When change comes, doing – and thinking – ‘the way we always have’, stops being a shortcut, and becomes a fast track to disaster.

When change comes, we need to rethink our assumptions but years of conditioning makes this very hard, if not impossible.

To succeed in a changing world, we must learn to question assumptions.

Question: But how?

Collection of differences

When I was an Economics Honours student, our small class was visited by John Stone, who later became Secretary to the Treasury. He was on a Treasury recruitment mission. Early in his talk he referred to the Karmel Report on Education and how poor it was. Prof Karmel had been our Head of Department so I felt honour bound to take up the challenge: “Professor Karmel is a highly regarded economist, so how come this report is as bad as you say it is?”

Consider the Committee!

He did not go on the defensive, instead he gave us a pen picture of each member of the Committee that had produced the report. I remember one fellow being described as ‘a businessman who believes that there should be ten people lined up outside his factory gate for every vacancy he has available’.

As a student I had naively looked at reports as objective statements of fact, carefully argued. But after that visit, I saw that all reports are in fact a compromise of the various views of the members comprising the Committee. Before the visit I had thought that an ‘independent’ report meant it was independent of the government, but then who chooses the committee?

Unless we know who is on the Committee and the way they see the world, it is hard to appreciate the conclusions reached. Often the titular head of the committee, the one whose name is associated with the report – as Prof Karmel was in this case – is chosen for his reputation, but the committee is chosen for their views (and there are more of them!)

Filling up from water trucks. Courtesy: Planet Thoughts.

In Australia, our regional cities are struggling for lack of activity and our capital cities are at risk of becoming disfunctional, particularly on the fringes, because of too much activity! The activity I speak of is infrastructure investment.

Why are we so hell-bent on developing mega cities? Big does not mean strong. It does not mean resilient. There is a lot of evidence world wide. Consider:

A horror story – current and continuing

The problems of Mexico City. See Mexico City, parched and sinking, faces a water crisis, an interactive report by the New York Times.

Now ask yourself, what lessons could we learn from this – and how many of the problems being faced there are exacerbated, even created, by high urban densities. And if water is not enough of a problem for you, consider transport, social and environmental issues. How many of our problems do we bring on ourselves? And how could we better manage by re-directing our growth efforts?

Recent Comments