No I’m not talking about huge structures, but about talking with Uber drivers about infrastructure decision making, and what I have learned from them.

Uber drivers are business people, they are characterised by having a drive for improvement of their lives and are often driving as a second career or while transitioning from one life circumstance to another, new job, new city, new family, etc. They are also polite.

As professional drivers they have a serious interest in transport infrastructure, especially roads. As service providers they will listen to customers’ stories. My drivers are often surprised when I voice the opinion that we don’t need more lanes, roads and tunnels; especially if we are in slow-moving traffic. There then follows a discussion, usually around 20 minutes, that covers the underlying needs for roads, traffic loads and the factors that contribute to peak congestion, the available solutions to the problems of road transport and the contribution that smart, connected technology can make to the problems of city life.

Since my drivers are constant consumers of connected technologies (GPS, booking apps, forecasting software) they have no trouble understanding the benefits that flow from the ideals of “Smart Cities” and easily understand that improvements flow from having information sources connected. They see that transport issues are directly related to things that can be adjusted with a connected view of the world. They also comprehend that the technology needed to address these issues has been available for years, and that it is the lack of integration of business, government and social information and policy that retards us.

What I have learnt from Uber drivers is that a conversation of 20 minutes can change a person’s understanding of infrastructure needs completely, from a view that continuous infrastructure construction is essential to a view that the solution to congestion of all kinds can be addressed with understanding and leadership.

Smart cities are coming, but I’d like the benefits now. Rather than upgrading highways, I’d like to see freely available information that can be used to tell drivers that leaving 15 minutes later will get you to your destination at the same time and with less fuel and frustration. Then service providers like Uber can give me an option to have a cup of coffee before my car arrives and everybody wins.

That’s interesting! I wonder why?

Over the last few posts, I have been looking at assumptions. Questioning assumptions is a way of more fully engaging with the ideas presented, of getting involved in the dialogue.

However asking ‘Why?’ should not be an excuse to let loose our inner 4-year old. We owe it to our own understanding and that of others to say ‘why we are asking why’.

Is it because we genuinely do not understand and want to know more (a neutral stance)? Then, let’s be honest and say so. Admitting we need to know more is a sign of intelligent recognition of our own (current) limits.

Often it is because we believe the assumption to be at fault and we are seeking to trip up the speaker with our question. This is not such a neutral stance. It is also probably responsible for our reaction when our own assumptions are challenged, to vigorously defend them and to suppose the questioner must be at fault – and probably just a bit stupid! So now we have an antagonistic situation where neither party learns anything.

There is a way out of this negative situation. Whether it is your assumptions that are being questioned, or the assumptions of others are arousing doubt in you, the most productive reaction is to say “That’s interesting! I wonder why?” Why is my assumption being questioned? Why am I having a gut reaction to the assumption of another? In both cases, by all means think through possible answers, but be wary of too quickly coming to a conclusion. Ask! But in a spirit of genuine, interested, curiosity. If you preface your question with “That’s interesting!” (and mean it!) you will be surprised by the genuine conversation that can follow.

Thoughts?

What will happen next?

In the last post I suggested that we shouldn’t be shy about questioning assumptions. But what? ALL assumptions?

Assumptions serve a purpose, otherwise they wouldn’t have lasted so long. They enable us to take shortcuts. Suppose I assume it is going to be sunny and don’t take a coat when I walk to the neighbourhood shops and get caught in a downpour. What are the consequences? I get wet and I am uncomfortable. But it doesn’t last long, and I am the only one affected. True, it would have taken but a moment or so to check my iPhone, so I probably also feel an idiot. But that’s it. Cost is small, temporary, and impact is limited.

Now consider an infrastructure decision where:

- the costs are large,

- the consequences last a long time, and

- they impact many people.

So when the consequences are low, by all means save yourself the effort if you wish, but if they are high – and particularly when the consequences are to be borne by others – we owe it to them to check, to question, to verify.

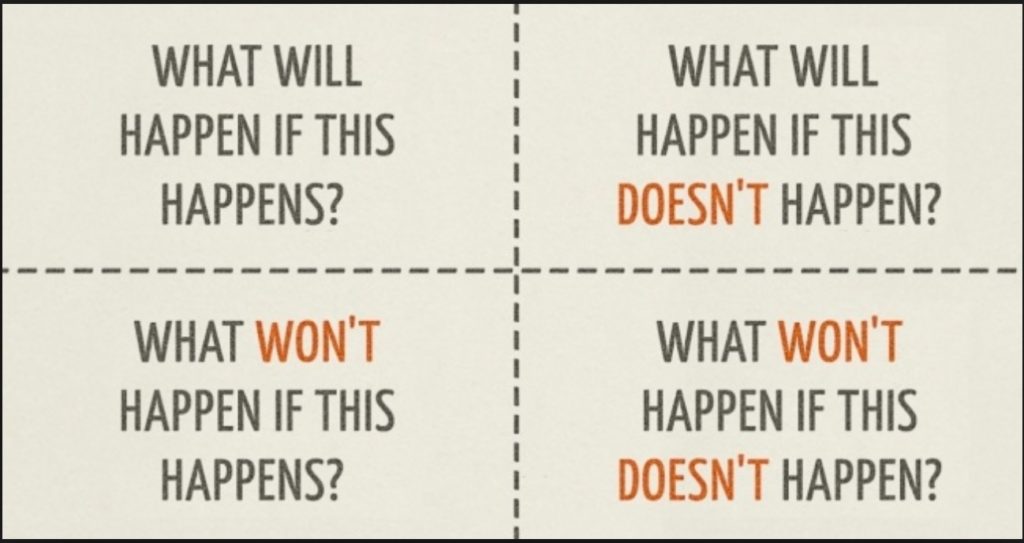

The DESCARTES SQUARE is a useful tool to ensure that ALL consequences are considered:

Collection of differences

When I was an Economics Honours student, our small class was visited by John Stone, who later became Secretary to the Treasury. He was on a Treasury recruitment mission. Early in his talk he referred to the Karmel Report on Education and how poor it was. Prof Karmel had been our Head of Department so I felt honour bound to take up the challenge: “Professor Karmel is a highly regarded economist, so how come this report is as bad as you say it is?”

Consider the Committee!

He did not go on the defensive, instead he gave us a pen picture of each member of the Committee that had produced the report. I remember one fellow being described as ‘a businessman who believes that there should be ten people lined up outside his factory gate for every vacancy he has available’.

As a student I had naively looked at reports as objective statements of fact, carefully argued. But after that visit, I saw that all reports are in fact a compromise of the various views of the members comprising the Committee. Before the visit I had thought that an ‘independent’ report meant it was independent of the government, but then who chooses the committee?

Unless we know who is on the Committee and the way they see the world, it is hard to appreciate the conclusions reached. Often the titular head of the committee, the one whose name is associated with the report – as Prof Karmel was in this case – is chosen for his reputation, but the committee is chosen for their views (and there are more of them!)

President Trump’s protectionist stance has been cemented by executive order withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Protectionism has swept Europe; Trump is not an isolated believer.

President Trump’s protectionist stance has been cemented by executive order withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Protectionism has swept Europe; Trump is not an isolated believer.

Much of the world’s infrastructure is built by international firms, their success built on scales of economy and expertise.

In the new protectionist environment, major infrastructure will increase in expense and/or decrease in quality.

My question is – where are the economic advisers, educators and leaders that help people understand the facts of globalisation, rather than the beliefs about globalisation?

Sydney, the second most expensive city in the world. The new Premier, Gladys Berejiklian, declares it “the biggest issue”.

Sydney, the second most expensive city in the world. The new Premier, Gladys Berejiklian, declares it “the biggest issue”.

Nationals leader Barnaby Joyce tells us to accept it.

But why?

I see this as a complete failure of leadership, and of understanding.

Sydney is lovely, beaches, rivers, parks, infrastructure. There are beautiful beaches for the length of the eastern coast. There are rivers and creeks everywhere. Parks abound. So infrastructure is key to the attraction of Sydney, and to the escalating costs, congestion and other trials for our leaders.

To quote “Field of Dreams” “If you build it, they will come.” And they do, by the thousands.

I spoke to a group of young people and asked them why they moved to Sydney, “because it is close to everything” they told me.

Building more infrastructure in our capitals generates more demand to live in our capitals.

Our regional centres spend year after year, planning different ways to improve the lot of their citizens, without significant success. The deck is stacked against them.

Until our secondary cities can offer proximity to services (and that means infrastructure) they will remain a “negative good” in the minds of our young people, our new people and our businesses.

Long term planning is necessary to relieve the pressure on our exploding Capitals and bring equity to our regional centres. We don’t need a way to build more free-standing dwellings in Sydney. We need to lift the service provision in other areas.

How can this be done?

We assume that ‘big’ events and ‘big’ infrastructure create jobs. But is this true?

We assume that ‘big’ events and ‘big’ infrastructure create jobs. But is this true?

In the last post I said the 1985 Grand Prix was ‘only slightly better’ – at creating income and jobs – than the ‘next best thing’ the State could have done with its money. What was that ‘next best thing’? Surprising as it might seem – Creating more public service jobs! Creating jobs directly by increasing the supply of doctors, nurses, teachers, maintenance personnel and assistants of all kinds, does two things. It directly increases the services received by the community thus improving lifestyles. And it creates lasting jobs, ‘bankable’ jobs, that increase economic stability and well-being the way temporary jobs, such as those from construction, never can.

Why not stop talking ‘jobs’ in general and talk ‘good jobs’ – permanent and sufficient to support a family, as the minimum wage was always intended to do. Or better still, let us think of the outcomes that we want, and how we can get them.

When the first Grand Prix was held in Adelaide in 1985, government officials touted how beneficial it would be. However, they were not able to produce a shred of evidence to support their enthusiasm. So the Economics Society of South Australia, jointly with economists from Flinders and Adelaide Universities and the Tourism Department, examined that first Adelaide event. It was the first and most complete economic analysis of any special event and was cited in every study on the subject for over twenty years. What did it find? In terms of employment and income generation the Grand Prix was only marginally better than the next best thing and then only because the Federal Government gave the State a grant! The more enthusiastic the announcement – the more it pays to check!

When the first Grand Prix was held in Adelaide in 1985, government officials touted how beneficial it would be. However, they were not able to produce a shred of evidence to support their enthusiasm. So the Economics Society of South Australia, jointly with economists from Flinders and Adelaide Universities and the Tourism Department, examined that first Adelaide event. It was the first and most complete economic analysis of any special event and was cited in every study on the subject for over twenty years. What did it find? In terms of employment and income generation the Grand Prix was only marginally better than the next best thing and then only because the Federal Government gave the State a grant! The more enthusiastic the announcement – the more it pays to check!

The same goes for the enthusiastic job promises for new infrastructure proposals. Ask yourself how valid they are – and how they have been derived.

Reference: The Adelaide Grand Prix, 1985, published by the South Australian Centre for Economic Studies.

Infrastructure – ‘if there is a consensus right now in American politics’, says the Economist, ‘it must be that infrastructure spending is a good thing. It employs workers, improves economic efficiency and, at the moment, can be financed at rock-bottom bond yields. So why don’t governments get on with it’ The same could be said of Australia. But just because many people believe it doesn’t make it true. (We used to believe the world was flat!) For example, how exactly does spending $1.6 billion on NSW Sports Stadiums improve economic efficiency? How does it plug the so-called ‘black hole’ of infrastructure expenditure that will stop the NSW economy going backwards? How many jobs are created? How long will they last? . It is about time we started asking these questions and more – demanding answers! Yes, us!

Infrastructure – ‘if there is a consensus right now in American politics’, says the Economist, ‘it must be that infrastructure spending is a good thing. It employs workers, improves economic efficiency and, at the moment, can be financed at rock-bottom bond yields. So why don’t governments get on with it’ The same could be said of Australia. But just because many people believe it doesn’t make it true. (We used to believe the world was flat!) For example, how exactly does spending $1.6 billion on NSW Sports Stadiums improve economic efficiency? How does it plug the so-called ‘black hole’ of infrastructure expenditure that will stop the NSW economy going backwards? How many jobs are created? How long will they last? . It is about time we started asking these questions and more – demanding answers! Yes, us!

The ‘group for building stuff’ (post 20 Jan) focussed on construction. The reserve bank idea focusses on financing. Both of these miss the point – by your traditional country mile. What is the point? Probably best explained in the title of Brett Frischmann’s book “Infrastructure – the social value of shared resources” The whole point of infrastructure is not so much what IT does as what it enables US to do! That’s the social bit. The ‘shared resources’ refers to the fact that, unlike our iPhone or car, infrastructure is not owned by any one of us alone, but by all of us together. Thus we need a representative group decision.

The ‘group for building stuff’ (post 20 Jan) focussed on construction. The reserve bank idea focusses on financing. Both of these miss the point – by your traditional country mile. What is the point? Probably best explained in the title of Brett Frischmann’s book “Infrastructure – the social value of shared resources” The whole point of infrastructure is not so much what IT does as what it enables US to do! That’s the social bit. The ‘shared resources’ refers to the fact that, unlike our iPhone or car, infrastructure is not owned by any one of us alone, but by all of us together. Thus we need a representative group decision.

So rather than give the job to some group that can only do a partial – and therefore poor – job, how do we improve government decision-making?

Recent Comments