Can’t stand economists? I often don’t care much either – and I am one! But this week I am proud to be among the number of ‘new economists’, economists for whom human beings are actually people, and the whole reason why we engage in economic activity, and not mere dispensible cyphers in the production cycle.

Kate Raworth, author of “Doughnut Economics – Seven ways to think like a 21st century economist” and the team at Rethinking Economics got together to issue a challenge to find an 8th way. Contributors could use any medium but they had to tell their story in 3 minutes or less. There were three sections, one for schools, one for universities, and one for ‘everyone else’. I like the emphasis on the young – where better to get new ideas?

Last Friday I posted the first place University Winner, “Legal Rights for Nature” voiced over a video of beautiful New Zealand. That encouraged me to see what the other winners came up with. You might like to see them too. So go here for the Schools winners (great ideas from passionate young people, a joy to hear and watch – they all use video, they are young!), the University winners and Everyone else.

If you are asking yourself why, as a non-economist, this should be of interest to you, I will draw your attention to a brilliant article in the New Economics Network of Australia (NENA) Journal by Steve Liaros “Economic Disruptions will reshape our cities” His thesis is simple: “Economics is about how we organise ourselves to satisfy our needs and wants. This ultimately translates into the arrangement of human settlements; the spatial relationship between living spaces, work spaces and their connection to food, water, energy and other resources needed for surviving and thriving. The economic disruptions mentioned above will transform our cities and the patterns of human settlements.”

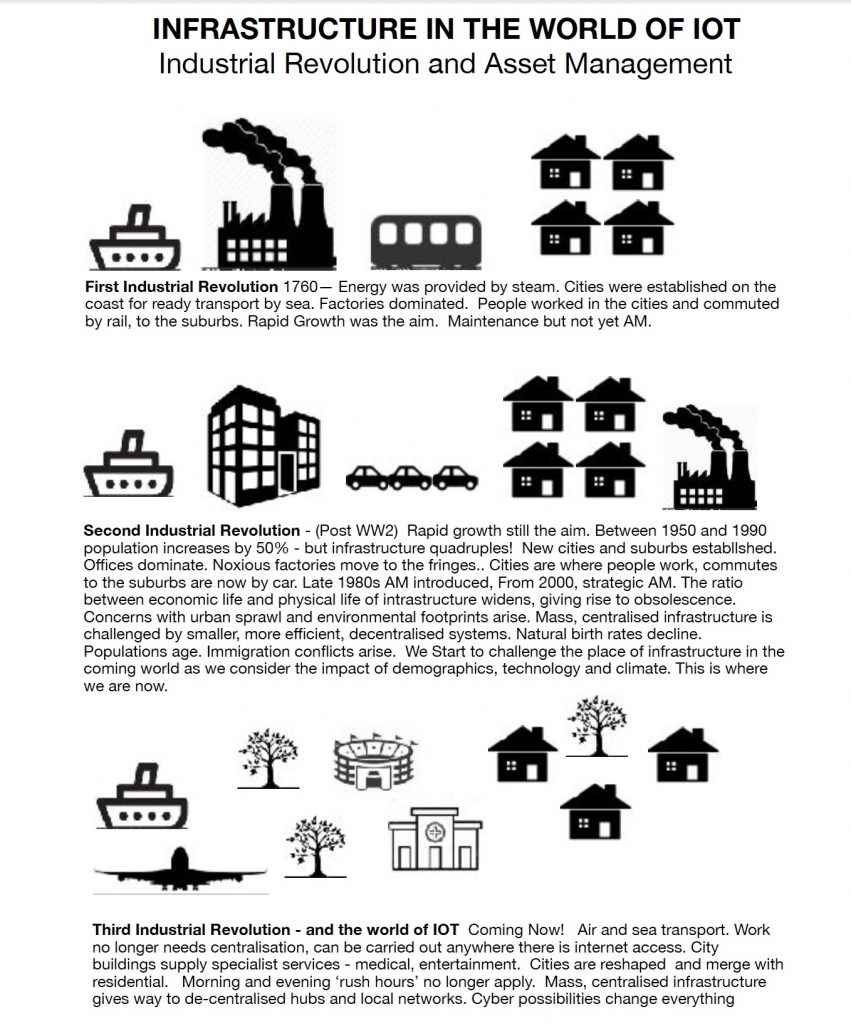

What delighted me about Steve’s article is that it is a beautifully argued elaboration of the story of the next stage of AM, that Jeff Roorda and I outlined in our article ‘The Third Asset Management Revolution’ back in April 2018. The original graphic for that story is reproduced here.

So there you are – economists and asset managers on the same page! Who would believe it?

SEVEN SPECIFICS OF BEING A STRATEGIST

SEVEN SPECIFICS OF BEING A STRATEGIST

We were talking about asset management – of course! – but more specifically about ‘thinking like a strategist’ when my friend and colleague, Ruth Wallsgrove, asked:

‘What would a strategist do that a professional engineer, accountant, or administrator would not?’

Now the truth is that any professional can think like a strategist, and often does. The trick to doing it better is to do it consistently, consciously, and in collaboration with others, in other words – corporately! So What does it mean to ‘think like a strategist’? Here are what I consider the 7 specifics.

- The Goal – Strategists adopt a big goal, the aims and objectives of the organisation they serve. They recognise that once the prime objective of their organisation is recognised, there may be many different ways to achieve it, in addition to those already identified – and they look!

- The Time Frame – Not ‘now’, and not ‘then’, but rather ‘from now to then’. A focus on what needs to be done to plot the path from the current situation to the desirable future. Such a path needs to be flexible and allow for adjustment as changes occur. (i.e. there is always a Plan B. C…)

- The Scope – the whole organisation and its wider social and environmental context

- The Reason – never ‘because XYZ is doing it’ or ‘because we have always done it this way’ (or even because it is new, innovative and exciting) but because, on balance and considering the options, it is the best way- for now -of achieving the goal. Always reviewing.

- The Attitude – Pragmatic (think Machiavelli), do what works, but analyse why it works. Curious. Sceptical. Analytical. Challenging.

- The Awareness – Strategists are not Superman and do not attempt to be. They know they need, and they fully appreciate, the contribution of others: professionals, tradespeople, users. The stance is one of willing collaboration.

- The Communication – understanding what drives the actions of others is key to the way in which ideas can and should be presented to be effective. People don’t fear change, they fear change being imposed on them. The art of good communication is winning hearts and minds. Strategists listen for more than words, they attune to the emotions of others (feelings of fear, trepidation, courage, hope)

The key difference between the Strategist and Other Professionals can be seen in the goals that they adopt.

Take Backlog for instance. A maintenance engineer will see the need purely in terms of the asset, its reliability and ease of operation. He will generally not see that the resources needed to achieve this reliability and ease of operation that could be used elsewhere in the organisation, and possibly achieve even greater good.

Take KPIs. An accountant may see, and even promote, rules such as debt ratios or productive staff: overheads ratios because these are manageable by her division. She may not even see the damage that is being caused to overall corporate goals by such rules.

Or take “finished staff work”. Any administrator that insists on finished staff work as the sine qua non of excellent administration has to accept old ideas thus ruling out new ones. Easier on him, but not necessarily to the benefit of the organisation.

Each of these is an instance of ‘solo thinking’

Solo thinking is ‘what’s best for me, my performance, my KPI’ – rather than ‘corporate thinking’ or what’s best for the organisation or community.

Organisations bring this upon themselves to a large degree by failing to articulate their goals, and especially their values. They also bring it on themselves by not encouraging and rewarding the strategic behaviour that would serve them better.

Thinking like a strategist, is ‘thinking holistically’ (I realise this word scares the living daylights out of many people, but it really is necessary!)

Professionals can improve their ability to ‘think like a strategist’ by moving ahead in any of these 7 specifics

Of Hammers and Nails

If the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail! But the reverse can also be true as I found this week. If you have a nail you cast around for what can be pressed into service as a hammer (A meat tenderiser works well.)

My philosophical nail is the problem of sound infrastructure decision making and it turns out that, even when I think I am taking time out to relax, the hammer search continues.

1. “13 Minutes to the Moon”

This is a new BBC podcast series that I am listening to that covers the planning and the almost decade-long lead up to the Apollo landing. The ’13 Minutes’ refers to the last 13 minutes before the landing when a number of times problems arose and it very nearly didn’t happen. Although you know the end of the story, the premise behind this podcast is that few of us really know the beginning. It is a documentary style podcast with lots of audio clips from those involved at the time. Good to listen to.

It got me thinking.

JFK’s decision to put a man on the moon is regarded as the classical successful mega project, not only because he did what was considered an almost impossible task but achieving it generated magnificent technology spinoffs, moving America way ahead of the world in technology. However, there was a more serious reason for the project that went beyond mere scientific curiosity. The US needed to regain the upper hand in the Space Race where the USSR had made some spectacular early gains, gains causing anxiety in the American people as well as defence concerns for the government. Americans were used to thinking of themselves as the pre-eminent ‘can do’ people of the world and these early moves by the USSR were impacting morale. So, in that sense, JFK’s announcement could be considered a successful move whether or not Apollo actually landed on the moon. (At election times, how many mega project announcements could be seen simply for their announcement value?)

I started to think of other successful mega projects, like the building of the Panama Canal. Again there were multiple layers of reasons for the project – defence, trade, global power, engineering daring do – and, of course, the use of new and untried technology to solve both anticipated and unanticipated problems.

It led me to ask the question – what are the characteristics of succesful mega projects?

2. Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Maybe it was thoughts of engineering success, or maybe the resurgence of interest in rail projects recently (the Very Fast Train, the Inland Freight Rail Track, the Melbourne Metro Loop), but my thoughts turned to the legendary Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who, amongst other things, masterminded the rise of rail in the UK. I wasn’t many pages into Steven Brindle’s “Brunel: The Man Who Built the World (Phoenix Press, 2006) before I started to see parallels with the time in which Brunel lived and where we are now.

When Brunel was born, (1806) England had just won a great naval victory against France – using wooden ships powered by wind! Most people at that time travelled by horse power and buildings were made of brick or stone. By the time he died in 1859

“ iron-hulled and steam-powered ships had arrived, pioneering new materials and methods of construction had been utilised in the fabrication of buildings that – in their scale and design – were like nothing man had ever constructed before and the road and the canal were being challenged by the new railway system with horse power gradually being replaced by steam power.” Brindle, Steven. “Brunel: The Man Who Built the World (Phoenix Press).

The Age of Disruption

The changes that occurred during the 50 odd years that Brunel lived, relatively speaking – power, transport, organisation and governance – were, at the very least, as disruptive as those that we face today. The era of steam, iron and rail was just beginning and Brunel ran with it.

What, I wonder, would Brunel be doing today?

I doubt that he would be building rail (the equivalent of the status quo wind powered wooden ships in Brunel’s time). Maybe he would be designing track for automated driverless cars and carriages, and building in solar energy access. Or maybe implementing the Hyper-Loop? In any case, would he not be advancing the state of technology?

Which brings me to ask the following questions:

-

Do mega projects need a technology advancement component to be successful, especially today, when technology is driving everything?

-

What other mega trends, if any (climate change, demographics) trump this or can/should they also feature?

-

Does a mega project require a ‘mega’ purpose – e.g. defence, global domination, economic or environmental survival?

Recent Comments