As a board member of several boards I learnt to be suspicious of a ‘one-off’ reason/excuse for failure. Especially if the same problem returned but was ‘explained away’ with a different ‘one-off’ answer. It was always worth drilling down for the root causes, always worth examining the process.

As a board member of several boards I learnt to be suspicious of a ‘one-off’ reason/excuse for failure. Especially if the same problem returned but was ‘explained away’ with a different ‘one-off’ answer. It was always worth drilling down for the root causes, always worth examining the process.

A poor outcome can be used as an opportunity to improve a process. You will find that the trust in you and your processes will increase if you do, as illustrated in the following two stories:

1. The Quality Control Manager of a large white goods industry tells how sales considerably increased when he took the trouble to explain to sales staff what problems had occurred in the past and what had been done to ensure that they would not happen again. The sales staff used these stories in their conversations with potential buyers who were impressed by the quality improvement processes involved. They bought into the process – and the product. But even more interesting, he told me that if customers had had an initial problem with a product butit was fixed promptly and courteously, they became more loyal customers than those who had not had a problem at all! The reason is that with their good experience of correction, they now trust the process.

2. This is a personal story: I was working on a report, one of a series, for the South Australian Public Accounts Committee, and discovered a flaw in the modelling – at the 11th hour! The Committee had approved it and the House had been advised we would be tabling but when we sat down to write the press release it became evident something was wrong. Worse, I had no idea how to put it right.This presented somewhat of a problem as the rules are that once the Committee commences an investigation, it must publish its findings. Nobody had noticed, and perhaps nobody would, but I knew it was there. We could not let it go ahead and had to advise the House that there would be a delay. In the event I was able, after much further and anxious work, to find the solution. But I was convinced that after this embarrassing hiccup the Committee would never trust my judgement again and I was prepared for a hard time when I presented the next report in the series. It never came. In fact, they were less, not more critical and searching. I was very puzzled. The Committee Secretary grinned: “Why should you be surprised? They now know that the process can be trusted, for when the going gets tough you will protect them from embarrassment at the cost of your own”. That poor outcome had, paradoxically given me an advantage! With the chance to refine and demonstrate the strength of our checking procedures, trust levels went up!

Question: Could this be an answer to our decision-maker’s dilemma’s (Oct 21 and Oct 25)?

It happens a lot! A senior staff member visits another country, sees something new, comes back full of enthusiasm to have the system installed here. His idea is new and exciting and it is given consideration. Time passes, the protagonist commits all his energies to getting the new project accepted and he is successful. In the meantime, over in the original country, experience with the new system is already throwing up a great many problems. Already the original country is starting to regret adopting the idea and is making excuses for the problems that have already arisen. The protagonist and his team, of course, hear about these problems.

It happens a lot! A senior staff member visits another country, sees something new, comes back full of enthusiasm to have the system installed here. His idea is new and exciting and it is given consideration. Time passes, the protagonist commits all his energies to getting the new project accepted and he is successful. In the meantime, over in the original country, experience with the new system is already throwing up a great many problems. Already the original country is starting to regret adopting the idea and is making excuses for the problems that have already arisen. The protagonist and his team, of course, hear about these problems.

Now they have a decision to make. Do they bring these problems to the attention of their superiors? If they do so, their position on the most innovative departmental project team, which is bringing them lots of interest and kudos, is at risk. Besides the directors, department chiefs and even the Minister have already made favourable noises about the project. Not so much that it could not be quietly shelved, but still it could be a bit of an embarrassment. Do they risk embarrassing their seniors or go ahead with the project despite the serious objections now being raised overseas?

This problem is not confined to the public sector, and is certainly not avoided by contracting out the work to the private sector.

Questions:

- What are the arguments in favour of change in these circumstances?

- What are the arguments in favour of doing nothing?

- Would a change in the system help? If so, what?

In his October 11 post, Gregory introduced the trolly problem and asked whether it is ethical to not take action when by doing so you could save a life. It is a tricky problem, a real ethical dilemma which is why the trolly problem has lasted so long in the literature. It might seem that as advisors on asset decisions we are never in such a dire life-or-death decision, yet is this really so? Consider the Railway Signalling Project.

In his October 11 post, Gregory introduced the trolly problem and asked whether it is ethical to not take action when by doing so you could save a life. It is a tricky problem, a real ethical dilemma which is why the trolly problem has lasted so long in the literature. It might seem that as advisors on asset decisions we are never in such a dire life-or-death decision, yet is this really so? Consider the Railway Signalling Project.

The signalling system was part of a larger redevelopment of the railway station and had taken many years to design and develop and to pass all the various hurdles that such large scale public developments require. It had also languished a long while with the cabinet sub-committee entrusted with making such decisions. Now, during this time it had become perfectly obvious to all the departmental protagonists that there was a far better signalling system now available, one that would be cheaper, easier to install and maintain and far more reliable. The question was: Do we issue an amendment to the original design to take account of this new development which would invitably slow the already lengthy procedure even more, but would save considerable money and, quite possibly, lives because of the greater reliability of the new system?. The ease of installation of the new system would allow us to recoup some of the extra planning time involved. Or, now that we are so close to the finish line and have spent so very much time in deliberation already, do we simply run with the inferior system and say nothing?

The organisation chose the latter course of action and the railways thus ended up with a more costly and worse performing system than it could have had.

Question: Were they right to have done so? What would you have done?

“When the first attempts at systematic weather forecasting were made, one idea was to look back through the records for a day where the weather was much the same as the day when the forecast was being made. The assumption was that the weather on the following day would be the same as the weather on the following day in the historical past. But surprising events are always occurring to disrupt this sort of forecasting.” (from Len Fisher’s talk on the ABC’s Okham’s Razor, 11 May 2016.

“When the first attempts at systematic weather forecasting were made, one idea was to look back through the records for a day where the weather was much the same as the day when the forecast was being made. The assumption was that the weather on the following day would be the same as the weather on the following day in the historical past. But surprising events are always occurring to disrupt this sort of forecasting.” (from Len Fisher’s talk on the ABC’s Okham’s Razor, 11 May 2016.

We laugh now at the absurdity of these first weather forecasters. However, many in the stock market still analyse charts of past stock prices to predict future changes (this is a bit more complicated, perhaps, but it still seeks to find answers to the future from the past) At least, if you get it wrong with stock prices, you lose a bit of money but can try again tomorrow. But if you apply these ‘looking back’ ideas to future infrastructure investment decisions that will impact our communities for decades, that is a very different matter.

Thirty years ago when I became interested in infrastructure planning, it was common to take a rising trend and simply extrapolate it and although it often resulted in major oversupply, we still did it. And we are still doing it! We just use more complicated algorithms.

But if not extrapolation of the past, what techniques are available for anticipating a changing future?

Here is a story about looking forward that you might enjoy.

Here is a story about looking forward that you might enjoy.

Many farmers use windmills to run bores for stock watering but pumps allow water to be extracted from much deeper resources. It is critical, however, that the pumps work or the stock dies. A friend had set up a business in selling – and servicing – pumps to farmers and his business was flourishing. He would routinely drive out and check all the pumps to ensure that they were working well.

Then he had the idea of buying a drone to do his survey work for him, but not a $500 hobbyist model, he decided on a top of the line model from the leading drone producers in Israel. He sent off his $27,000 cheque – only to have it returned to him! The Israeli government said it was not prepared to sell it to him for security reasons!

This was about 8 months ago. Not to worry, he said, soon there will be satellites I can connect to and I will be able to check the pumps using my smart phone!

This is a fellow who is keeping his eye on the rapid rate of technology change.

No specific question today – just enjoy!

Switch (courtesy Falk2)

If we have information that can lead to better decisions, can we fail to act? Can we excuse ourselves with “it’s their job”, “not my responsibility”, “I don’t want to be involved”.

Philippa Foot devised a thought experiment in 1967, routinely called the “Trolley Problem”. The experiment involves a train (trolley) heading toward 5 workers. The train is a runaway and all 5 workers will certainly be killed if nothing is done. There is a side track with only one worker and you are in the right place at the right time to make a decision. You can activate the rail switch, diverting the train and resulting in a single certain death. Or not. There is no time to alert the workers, or gain assistance; the train can’t be stopped.

As a tool to teach ethics this particular experiment is deceptively simple, should I sacrifice 1 to save 5? It does however raise numerous questions, “am I obliged to act?”, “do I have a duty?”, “is interfering wrong?” “do I act morally or ethically?”, “do I act for the greater good, the good of the people involved, or for myself?”

This dilemma is very long lived and has captured the imagination of the professionals and public. There are many variations – is it Ok to stop the train by pushing someone in front of it? What if that person was responsible for the runaway train? What if the workers could be saved by sacrificing a bystander, or a loved-one?

When anyone is faced with making a decision at a switch they can make a moral choice, an ethical choice, a popular choice, and when making that choice they can include longer time frames, wider consequences, how the action will make them feel, how others will think of them.

Questions today: When it comes to infrastructure decision making, when our decision takers are standing at the switch, how do we know if we should contribute to the conversation? When would we join in if we do, and with what level of action?

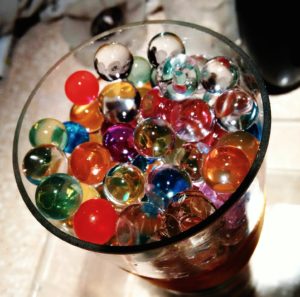

“General equilibrium”, an economics colleague explained, “is like a bowl of marbles, move one and we have to reckon with a change in every other one. Depending on the location of the original marble, the change will be large or small, but there will be always be a change.”

“General equilibrium”, an economics colleague explained, “is like a bowl of marbles, move one and we have to reckon with a change in every other one. Depending on the location of the original marble, the change will be large or small, but there will be always be a change.”

Thinking now of energy, a breakthrough in battery storage development would be the equivalent of moving a marble at the very bottom of the bowl. Anyone following the technical developments in batteries, and the vast resources now being devoted to this exercise, would expect to see this happening within the next five years (and probably sooner rather than later). In other words a breakthrough in the length of life and the economics of solar energy (and wind energy) storage is an almost certainty. But what then?

As important as technological innovations are, they are not the end of the story. In fact they are just the beginning. When battery storage possibilities improve, here are some of the impacts we can expect to see – a change in social attitudes towards energy usage; changes in manufacturing to take advantage of this; a great increase in the demand for solar panels; an increase in the willingness of some to go completely off grid; but also an interest of many more in adapting the present distribution network to serve localised production and sharing of power. Localised power production and distribution will enable greater security from events such as the recent power outage in South Australia and future impacts from climate change, as well as attacks on our critical infrastructure.

However, the change in demand for distribution networks will present a business model challenge for network owners which is why ‘economic innovation’ is now needed. No change will take place unless a profit can be made from it. Profit is not a dirty word. It is essential to good resource allocation.

So my question today is: what do we know of research into new business models that can promote and support the adaptation to distributed production and distribution that solar and wind power combined with good battery storage can make possible?

The value of “value management”, as Mark Neasbey, Director of the Australian Centre for Value Management, has illustrated in each of his previous posts, is in challenging what we think we know. In “The Power of ‘What if?'” he reveals how questioning a ‘given’ led to a radically different solution and a saving of hundreds of millions of dollars. Mark writes:

The value of “value management”, as Mark Neasbey, Director of the Australian Centre for Value Management, has illustrated in each of his previous posts, is in challenging what we think we know. In “The Power of ‘What if?'” he reveals how questioning a ‘given’ led to a radically different solution and a saving of hundreds of millions of dollars. Mark writes:

The types of things that are generally in a list of givens include:

- a law or regulation that has to be complied with;

- a technical performance requirement – be it a range or a set minimum or maximum number or a specific number – which can represent dimensions, volumes, rates and so on;

- a limiting boundary or barrier or a technical constraint;

- financial – e.g. an amount not to be exceeded or specified sources of funding, interest rates and so on;

- ownership and operating arrangements;

- authorities and delegations;

- a specific time or date that the asset is required or to be disposed of; and

- application of a particular process or corporate policy.

[Not an exhaustive but just some main examples.]

Now the thing about such givens is that we develop our options or solutions accepting these, rather than challenging them. So they tend not to come into creative thinking processes, accept as a limitation. Yet what happens if its not really a given, rather it turns out to be possible to change it – even if only to treat it as an assumption?

A recent rail project to develop expanded train maintenance and stabling facilities began with a given that the existing mainline was fixed – it could not be changed. By not allowing it to be moved the project solution involved some complex and expensive engineering and infrastructure to manage the train movements into and out of the depot, which are planned to eventually have headways as short as 30 seconds. [Driverless trains.] There was also an effect on how the layout of the expanded facility could be realised – it was not going to be as ideally efficient as possible to operate.

During a value engineering review however, the effects of not moving the mainline to the engineered solution became clearly a cause – not of concern – but for a better appreciation of the opportunity forgone to create a simpler, more elegant engineered solution and at a huge cost reduction.

The mainline alignment had been stated as a given by the client early in the planning process. So all of the initial feasibility work and preliminary concepts evolved based on that given. What subsequently emerged in the value engineering review was that this arose from a decision not to acquire a particular developed property adjacent to the line.

By asking the simple question “what if…?” the team was able to show a much better outcome was possible – not only at a lower capital cost, but with significant long term reduction in maintenance and operational risks to the network.

Two important highlight lessons to me are:

- Do you have an understanding of what is being labelled or taken as givens for your assets and asset strategies?

- Do you have a process to all testing and challenging of such givens so decision-makers are aware of their implications?

The Task today: An answer to either of Mark’s questions OR an example of a positive ‘What if?” challenge of your own.

Recent Comments