“What’s the first step to a good Strategic Asset Management Plan (SAMP)? A bad SAMP…”

My ex-colleague Ark Wingrove’s saying has resonated with clients since he first coined it. You do not have to wait for perfection; the important thing is to start, knowing you can improve as you go.

It works not just because it’s true. Just having someone tell you you won’t get everything in Asset Management perfect first time liberates us to try. Otherwise – and this surely tells us something about the asset culture we pick up, and need to change – we get frozen in the headlights of needing to be right.

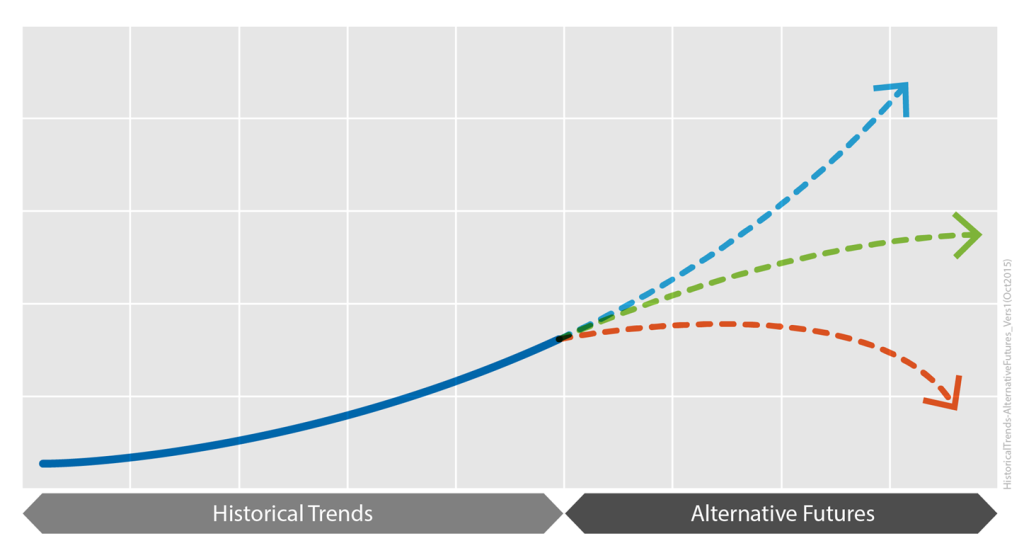

It’s a profound truth of AM that you will never know enough about the future; and yet you still have to have a strategy, you still have to plan, you still have to make decisions that matter. And so inevitably we will get some important things wrong.

The approach that the AM documents and processes we produce are all iterative is, of course, built into the diagrams, the 6 Box Model and the flow of ISO 55000, continuous improvement and the ’learning loop’ of Plan-Do-Check-Adapt. The idea that, above all, we can’t leap straight from muddle to highly sophisticated Asset Management Planning has long been recognised in Australasia. We have to build, step by step, our planning evolving with our increasing understanding.

But it just struck me that it’s not simply how we improve things as we know more. The real blocks are thinking we know more than we do at the start, and the fear that we will be exposed for not knowing enough – the toxic aspects of being an expert.

Years ago Penny Burns came in to take my Sydney team through scenario planning. The real achievement of this was to move everyone away from their confidence. From believing they could ever be certain about the future.

In an exercise around understanding our levels of uncertainty in risk training this week, someone asked – tongue in cheek – how we could ‘win’.*

The urge to be right is natural, I guess, but it also goes with all sorts of baggage. That we won’t even start unless we can be certain. That it is better not to try than to run the risk of being wrong.

As though, for example, a strategy for Asset Management is a test we have to pass.

The principle of evolving, getting better as we go but never reaching 100% certainty. What examples of positively ‘embracing uncertainty’ have you seen in practice?

*Calibration training based partly on the work of Douglas Hubbard, see his The Failure of Risk Management. If you have never come across this, aiming to show off that you’re right that will ensure you don’t get it right. (And even telling people this doesn’t help them, at least the first time around.)

Recent Comments