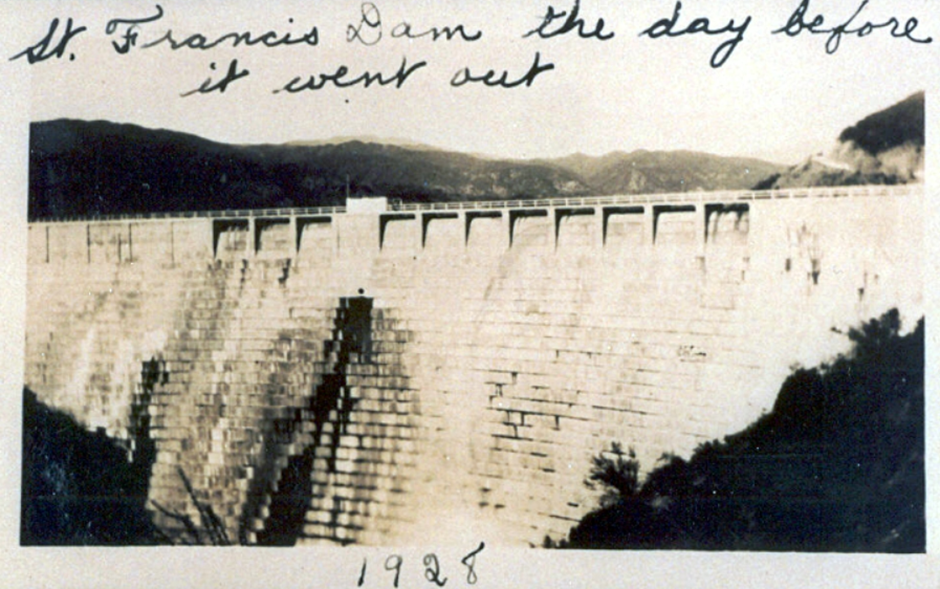

Last known photo of St Francis Dam before it collapsed, © scvhistory.com

You know when you hear something you never noticed before, and then hear about it again the very next day? (It’s known as the Mandela Effect.)

I mean, I saw Chinatown many years ago and so understood that there was a rotten heart to Los Angeles’ water supply, but I never thought about where the water comes from – or understood how it trashed a valley and its communities in the 1920s.

Originally called Payahǖǖnadǖ, meaning ‘place of flowing water’, Owens Valley is a now dry valley north of LA.

I work with enough hydro dams to be curious about dam failures – there have been a few catastrophic failures in the 20th century – so wanted to watch a PBS documentary about the total failure of St Francis Dam in the valley. It failed because of hubris. It did not make it past its first day in operation. But the documentary was about much more than the immediate collapse and the hundreds of people who died that day.

Los Angeles basically stole the water, buying up water rights surreptitiously and sometimes illegally. For some reason I can’t comprehend, it even memorialises the engineer responsible for the dam failure (and the overall aqueduct, which does still exist): Mulholland, of the Drive.

And the day after I watched the documentary, I read a review of a book titled Dust, by Jay Owens, using the Owens Valley as a 20th century example of humanity creating arid dust bowls where there were once thriving ecologies.

Metropolitan LA is a funny old place. I have spent plenty of time there as my brother moved to Azusa in the late 1970s, and retired to Orange County to the south. It was hailed as the city of the future once, but water is the big question mark, still. You would have to conclude that the LA basin is well beyond its carrying capacity, and perhaps always was.

Owens Valley, and St Francis Dam, seem suitable reminders of the challenge of sustainability. enshrined in the original BSI PAS 55 definition of Asset Management. The valley and its people – original and immigrant – paid the price for the development of a vast city region.

Not the first and surely not the last example, but a sobering reminder that water engineering is both hard, and not always on the side of the angels.

Thanks to Chad Dulac of Chelan County PUD, WA, for this steam-punk platypus

I just dutifully waded through a dismal history of the last five decades of British economic policy. Plenty of government mistakes, and nothing that really got past missing an empire. (The Tyranny of Nostalgia, by Russell Jones.)

Despite a less than adequate grasp myself of the mechanics of money supply and exchange rates, I wanted to learn lessons for we should be doing in future. And try to keep up more with Penny Burns, of course.

The book itself focused most on economic stability, and how that encourages good things to happen. Or at least doesn’t scare the horses. And something beyond short-termism and political self-interest.

But, at the very end, the author did have to conclude that successive British governments have done less and less on what truly underlies the ‘economy’: on developing skills, encouraging new ideas, and supporting infrastructure. On how to enable people to do interesting things, really.

And here is where talking about infrastructure comes in.

The physical infrastructure of water and waste water, power, transport and telecommunications isn’t something in its own right, assets for their own sake. It’s about enabling us to do what we need and want to do. Along with agriculture, education and health, it has to start with supporting Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. No-one too hungry or cold or isolated or poorly educated to reach for self-realisation.

In a country increasingly of “private wealth and public squalor” – used originally to refer to the United States – I come back to the sheer waste of potential in Britain, along with the heartache of poverty and lack of opportunities. It’s not like we don’t have plenty of really interesting challenges to apply our collective energy to.

Obviously no-one in the current British government has any kind of vision for community beyond their rich mates.

But what is our vision?

Dr Monique Beedles ran a fascinating webinar for the Institute of Asset Management on September 6 on why we should not talk about people as things you can put on a balance sheet.

As she put it, we of all people should recognise that people and assets are not interchangeable. People are ends, not means, with value independent of our economic utility.

Her intention is to rehumanise the discussion about people and work. A ‘people first’ strategy.

But this fits with her view on what’s really needed for good Asset Management, too: her hierarchy of what’s required starts at the bottom with Tech Smarts, through Biz Smarts, to what she calls Street Smarts at the top*. Or the qualities we need to bring to the table of humility, empathy and integrity.

I was particularly taken with her terms we should cut from our vocabulary: productivity, human resources, human capital.

I love the idea that those of us who manage things are in a particularly good position to spell out that people are not things. That people first is, of course, the right approach to physical infrastructure.

And though she didn’t capitalise it as a slogan:

Build Community, not Capital!

www.moniquebeedles.com for her AMP Peak paper, ‘Leadership in Asset Management: Why Your People are Not Your Greatest Assets’

*See her book Leadership Assets, A Whole-of-Life Plan for your Asset Management Career (2021)

Or, making sure we always ask who truly benefits by a new infrastructure project.

Infrastructure investment always attracts several groups with particular interest in the projects themselves.

There are the construction companies where it is all upside (work for them) and no cost, at least to them. They probably won’t even be around when the assets are in use.

There are internal project engineers who want cool things to build, whose interest in the assets once constructed can be minimal. That is to say, they don’t necessarily worry about handover of as-builts or how well the assets work after ten years. Their job is to do shiny news things!

And of course there are developers, whose interest extends to how much they can exploit the infrastructure – and with a long, long history of lobbying to the point of corruption.

I am not sure if the people who fund it always think about this. Assuming, of course, they have not already been captured by the lobbying and mindsets of construction companies and developers.

A lot of people like to see money invested in their neighbourhoods, at least until the construction noises start.

So, wearily, we have to take this on as infrastructure Asset Managers and stewards.

Like mad-eyed prophets calling out in the wilderness, and not necessarily honoured in our own country, nobody maybe wants to hear: Cui Bono?

Photo 247485510 / Asteroid Hitting Earth © Elen33 | Dreamstime.com

Don’t Look Up – as opposed to Now, or Back in Anger – is a 2022 witty parable on the climate crisis in which a variety of movie stars play more or less against type. It does not say much about infrastructure, except to destroy it all with an asteroid, but I was struck by the stupid economics.

When the Elon Musk-alike (Mark Rylance!) says how many trillions of dollars’ worth of rare and valuable metals are contained in the asteroid, one of the heroes mutters about how that isn’t going to mean anything when it destroys the Earth.

But I was struck by the very specificity of the pricing. As though price is an absolute, unaffected by destruction, or anything to do with other humans. Even without total destruction, surely living through the threat and even partial environmental chaos might change people’s enthusiasm, one way or another, for buying yet more mobile phones?

The Musk-alike means how many dollars he could get for the stuff in today’s market, not the value; it’s left to someone else, a corrupted government advisor, to suggest it’s enough money to cure hunger and poverty, but you know he’s just mouthing it. (And you can’t eat money.)

The trillionaire simply plans to be trillions richer. He has no sense of who will be around to buy from him. The ‘stuff’ is enough.

The dollars have some kind of fabulous independent existence.

Rather like the idea of how many dollars infrastructure construction generates. We know for sure lots of construction means lots of money for construction companies, but the value it creates is rather less easy to work out.

Both of these things – the $ worth of metals in an asteroid that probably can’t be used, the $ worth of building infrastructure any old place – are, I think, what some people call fetishes. Inanimate objects worshipped for supposed magical properties.

Out of context, we’re not even trying to work out what’s actually of value. It really is very stupid economics.

PS I recommend the film

The peculiar antics of Elon Musk in late 2022 prompts, once more, the question of whether tech billionaires are really the best model for our heroes.

During Covid, plenty of people realised how dependent we are on carers, paid perhaps a millionth of what Musk pays himself. We clapped for a very different kind of heroics during lockdown.

Infrastructure is an intriguing mixture: it’s technology to keep our societies going, not primarily to make money. Managing it well involves caring for stuff. We are not carers in the traditional sense – and many of us are paid better than nurses or teachers.

Of course, technology innovation and looking after other people are very heavily gendered in our society: stereotypically, techies are male, carers are female. Making an obscene amount of money from exploiting innovation is masculine heroics; working till you drop caring for someone else is feminine heroics. (There are plenty of men in caring professions, but that doesn’t stop the stereotype.)

Sometimes I feel we’re trying to work out what kind of heroes we want to be in asset management. There are plenty who fancy the innovation techie route, getting all excited about ‘digital transformation’ (cf. the call this week for papers by ReliabilityWeb on the subject, for example) and, probably, the well-founded belief this is an easier way to make money. There are others, more equitably spread between women and men, who are sure it’s mostly about people.

We shouldn’t be particularly surprised to see crude stereotypes echoed in our own profession. A colleague recently described the problem of dominance in AM by “fat middle aged white men” (he said he was talking about himself, and the fat bit was a joke) – a dominance that doesn’t thrill me. I find myself more alarmed by the failure to learn our own lessons about what it takes to manage infrastructure, and rush into anything techie. As though, this time, technology innovation will sort out all the problems. Including the tiresome need to think about people.

But, then again, it’s surely the mix, the dynamic tension, between technology and caring which actually appeals to many of us; that brought us into asset management in the first place.

In their excellent book The Innovation Delusion, Lee Vinsel and Andy Russell challenge both innovation and heroes as ideals – and propose instead the maintenance mindset and how to sustain our “human-built world”. I think this is partly what they mean, this interesting mix.

PS Their Maintainers are still going strong, by the way, with some assistance from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Siegel Family Endowment – see www.themaintainers.org

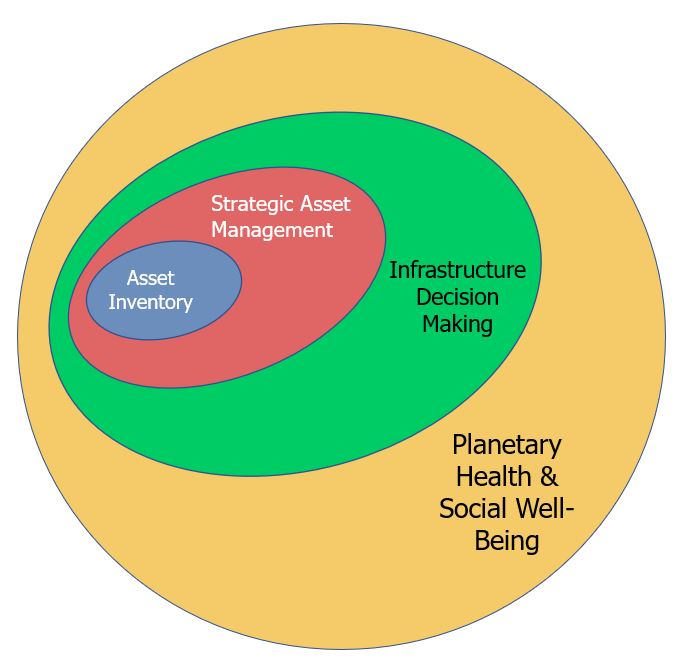

In May 2018, Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda wrote here about three ‘revolutions’ in Asset Management – later renamed ‘waves’, because that captures better the idea that one wave doesn’t supersede another.

Since then, we have discussed with each other and many others how Wave 1, ‘Asset Inventory’, is more successful if you already have in mind the vision of Wave 2, ‘Strategic Asset Management’ and how you are going to use all of the information you collect.

We have looked at what Asset Management practitioners need to develop to move on from this, to be able to look beyond our own organisations, to a bigger role in supporting our communities. We called this Wave 3, supporting better ‘Infrastructure Decision Making’.

We have even begun to imagine Wave 4.

As Penny puts it: whereas Wave 1 looked at WHAT we had, and Wave 2 looked at HOW we needed to manage it, Wave 3 started to ask WHO we were serving by our efforts. This has brought us now to start thinking more deeply about this question and about the next move, looking at the critical question of WHY.

As Asset Management practitioners, we have to ensure we are in the right positions of influence to be able to challenge existing infrastructure assumptions, which is what I think Wave 3 is all about. To look ‘up and out’, as Lou Cripps of RTD puts it.

But we can already spot that there is no point in being able to ask hard questions, if we don’t have the right questions to ask….

What do we mean by ‘better’?

Recent Comments