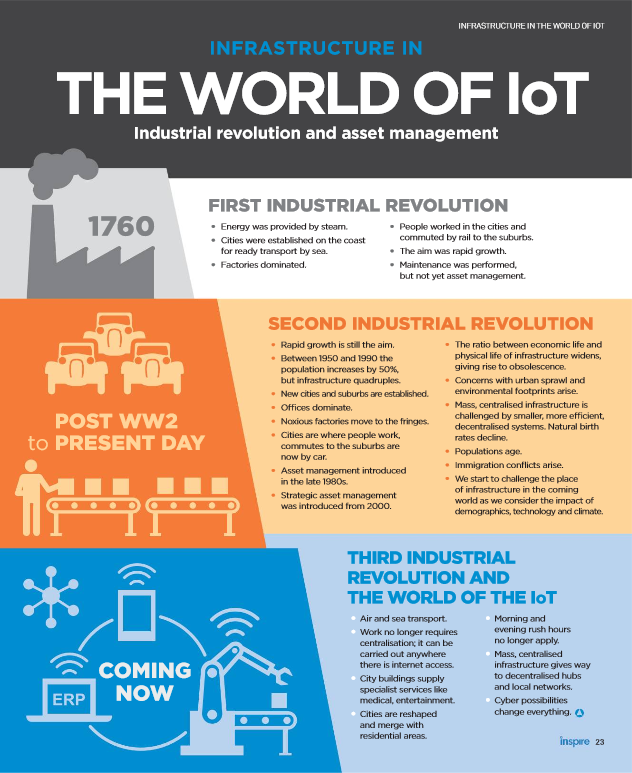

Thanks to the graphics team at IPWEA Inspire for their contribution to our graphic.

The article by Penny Burns and Jeff Roorda “The Third AM Revolution” of which this is part, can be found here

There is an economic principle called ‘diminishing returns’. This says, in effect, that your first hamburger is great, the second OK, but by the time you are on to your third and fourth, the returns in terms of enjoyment and allaying hunger are greatly diminished. Continue and the returns will eventually become negative. Of course, long before you become physically ill, the benefit:cost ratio will itself have become negative. This does not only apply to hamburgers. It applies to everything, including our policy settings. For a while the benefit of the new policy outweighs the disadvantages – until it doesn’t. We often fail to see the change because we are always looking backwards – justifying our current actions by the gains we have already made, and asssuming that these gains will continue.

There is an economic principle called ‘diminishing returns’. This says, in effect, that your first hamburger is great, the second OK, but by the time you are on to your third and fourth, the returns in terms of enjoyment and allaying hunger are greatly diminished. Continue and the returns will eventually become negative. Of course, long before you become physically ill, the benefit:cost ratio will itself have become negative. This does not only apply to hamburgers. It applies to everything, including our policy settings. For a while the benefit of the new policy outweighs the disadvantages – until it doesn’t. We often fail to see the change because we are always looking backwards – justifying our current actions by the gains we have already made, and asssuming that these gains will continue.

Consider that over the last several decades we have made great efficiency gains in infrastructure services such as electricity production and distribution by increasing the size of our production units and integrating our networks. There was a period (up to about the late 1980s) when it was always more efficient to build a new plant rather than renew an ageing one because technological improvements were increasing boiler size resulting in vastly reduced capital costs and considerable savings in labour.

Eventually two things happened. The technological gains slowed down. And risks increased. For one thing, if you can satisfy demand with 6 units of a given size, should one fail you have lost 1/6th of your total output. But when the size of units increases to the stage where total demand can be satisfied by just 3 units, then failure of just one unit reduces your capacity to serve by 33%. Gains slow down, risk costs rise. We can see a similar pattern in the integration of networks. Initially the gains are great, and obvious. We do more integration and we get further gains. But the more individual networks that are connected the greater the risk that an accident in, or mismanagement of, any link in the chain will have flow on effects to the others.

And so we get events such as the 2003 major blackout of the NorthEast of America which extended into Canada and, closer to home, the 2016 widespread power outage in South Australia that occurred as a result of storm damage to electricity transmission infrastructure. The cascading failure of the electricity transmission network resulted in almost the entire state losing its electricity supply. To add to our worries are recent accounts of Russian hacking into US nuclear power plants.

So big is not necessarily beautiful. But what’s the alternative?

Three words have dominated our thinking, our policy and our practice in infrastructure decision making over the last 30 years – efficiency, sustainability, risk. This is about to change.

Three words have dominated our thinking, our policy and our practice in infrastructure decision making over the last 30 years – efficiency, sustainability, risk. This is about to change.

Efficiency

With large, centralised, and expensive mass infrastructure needed to support public services, ‘efficiency’ was a key concern. But technology is making smaller, distributed, infrastructure, not only cheaper – but in today’s climate of cyber terrorist concerns – also much safer. We are now developing new de-centralised means of provision and our new concern is how safe and effective they are.

EFFECTIVENESS is thus becoming more important than efficiency.

Sustainability

For infrastructure ‘sustainability’ has been interpreted as ensuring long lifespans. We have designed for this and over the last 30 years we have developed tools and management techniques that enable us to manage for asset longevity. This, too, is now changing. With the shift from an ‘asset’ to a ‘service’ focus, functionality and capability have become more important determinants of action than asset condition. This shift is fortunate for it is needed if we are to address the many changes we are now facing – technological, environmental and demographic. At first we thought to ensure sustainability by building in greater flexibility. But change is now too rapid and too unpredictable to make mere flexibility a viable and cost effective strategy.

ADAPTABILITY is the new word. We need to design for, be on the lookout for, and manage for, constant change.

Risk

Risk has been the bedrock tool that we have used in the past to minimise the probability of both cost blow-outs (affecting efficiency) and asset failure (affecting sustainability). Risk management has been a vital and valuable tool. However ‘risk analysis’ implies we know the probability of future possibilities. Today we have to reckon with the truth that the ‘facts’ we used to have faith in, may no longer apply.

UNCERTAINTY is more than risk and requires different tools and thinking.

Effectiveness, Adaptability and Uncertainty.

With these new words comes a requirement for new measures, new tools, new thinking, new management techniques. Life cycle cost models were valuable in helping us achieve efficiency and sustainability and apply our risk analysis. What models, what tools, what measures will help us achieve Effectiveness and Adaptability and cope with Uncertainty?

What new questions do we now need to ask?

For years we have asked ‘what infrastructure should we build?’ Perhaps now we need to ask “What infrastructure should we NOT build?”.

In the last post

In the last post

I suggested that, when it came to new ideas in IDM (Infrastructure Decision Making), the usual sources of new ideas, namely academic research, think tanks and in-house research were limited in their ability to provide workable solutions.

If academics have an incentive to continue research rather than provide answers, who has an incentive to provide answers? If Think Tanks have an incentive to contain their solutions to the subset of possibilities supported by their funders, who has an incentive to look more widely? And if in-house research provides depth but is limited in scaleability, where can we look for answers that can apply over a wider field?

A Suggestion:

I am going to suggest that, curiously enough, it may be the often maligned consulting industry that is, today, most capable of producing the more interesting research outputs when it comes to infrastructure decision making.

There is a growing number of consulting companies that use their in-depth access to many organisations to test and develop ideas in their search for practical applications.

- They have the incentives: increased reputation and customer satisfaction lead to sustained and increased profit.

- They have access to some of the brightest of today’s asset managers, many of whom have, or are in the process, of developing post graduate research theses.

- They have detailed access to information from a large variety of organisational clients.

These are the elite consulting companies. They don’t have to be large, although access to a large client base helps. Small or medium sized consulting companies may achieve the same level of innovation by developing a sharper focus.

Of course, not all consultants necessarily act in this fashion. There will always be those who choose a ‘cookie cutter’ approach and try to fit your problem into an already conceived solution. But what you will see in the better, more innovative, firms are that they apply themselves to thoroughly developing an idea; they stick with it over the time it takes to bring it to fruition (often years); and they expose their ideas to others (in conference presentations and in papers on their websites).

Nearly always the effort will revolve around one or a few talented and motivated individuals. For this reason, it pays to follow the activities of such individuals in consulting organisations that you are thinking to use. LinkedIn is a good source for this.

Other Suggestions?

Where are new ideas in infrastructure decision making to come from?

Academia?

One might suppose so. Yet how many times do you get to the end of a promising piece of research only to find nothing that can be adopted for practical use, only an indication of potential and a recommendation for further research? Frustrating, yes, but unfortunately this is an academic necessity. In our ‘publish or perish’ world, where one published paper is used to generate the research funding for the next, producing a workable solution that can be adopted by practitioners is an academic ‘dead end’, and nowhere near as academically useful as papers that generate problems for further research.

One might suppose so. Yet how many times do you get to the end of a promising piece of research only to find nothing that can be adopted for practical use, only an indication of potential and a recommendation for further research? Frustrating, yes, but unfortunately this is an academic necessity. In our ‘publish or perish’ world, where one published paper is used to generate the research funding for the next, producing a workable solution that can be adopted by practitioners is an academic ‘dead end’, and nowhere near as academically useful as papers that generate problems for further research.

Think Tanks? Federal Inquiries?

If we cannot look to academia for useable research – that is research ideas that can be applied in practice – where else can we look? There are, of course, think tanks or public inquiries such as the Productivity Commission. These are usually very well funded and employ some of the brightest individuals. However, both the topics and approach chosen will of necessity be determined by the funding organisation or the incumbent government and may not be unbiased.

Public Service and Public Policy White Papers?

Once, excellent research papers were produced by the Public Service. In the 1970s and 1980s, the ability to produce well written and researched ‘white papers’ was a highly prized skill. However politicisation of the Service and the unfortunate elevation of the craft of ‘spin’, have taken their toll. There are still pockets of excellence in the Service, but, with downsizing, there are few instances of good research written to a rigorous standard and subjected to the test of knowledgeable peers.

Asset Owners, Managers, Decision Makers themselves?

What about in-house research by asset owners? This can often produce some very well researched and well written case studies. The difficulty with adopting the ideas produced, however, is that they are heavily dependent on the organisation itself – its prior development, its general culture, leadership and organisational knowledge. Such research produces interesting case studies but presents problems of scaleability.

So what are we left with? How do we progress?

Jeff Roorda continues the story he began with Motorways and Steam Engines (Mar 27)

In part 1 we introduced the difference between physical life and economic life.

In part 1 we introduced the difference between physical life and economic life.

Part 2 talks about certainty bias, that is, we pretend to be certain about the future even though this is an irrational and emotional response. The feature photo shows the I-35W Mississippi River bridge collapse (officially known as Bridge 9340). An eight-lane, steel truss arch bridge that carried Interstate 35W across the Saint Anthony Falls of the Mississippi River in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA collapsed in 2007, killing 13 people and injuring 145. The bridge had been reported structurally deficient on 3 occasions before the failure and ultimately failed because it was structurally deficient. The design in the 1960’s had not anticipated the progressively higher loads compounded by the heavy resurfacing equipment on the bridge at the time of failure. There was no scenario I could find that explained clearly enough for any reasonable non-technical person to understand, the likelihood and consequence of failure and the uncertainty of the safety of the bridge. After the failure, the courts found joint liability between the initial 1960’s designers and subsequent parties involved in managing the assets. The allocation of blame and acceptance of wrongdoing was highly uncertain, but lawsuits were settled in excess of US $61M. The strength and life of the bridge was uncertain and this was reported in technical reports but every person that drove over the bridge and every decision maker with the power to close the bridge had the illusion of certainty that the bridge was safe and would not fail.

As asset managers, our estimates of asset life have critical consequences but are uncertain. We estimate and report how long an asset will last before it fails, is renewed, upgraded or abandoned. This then determines public safety, depreciation, life cycle cost and our future allocation of resources. Whether we decide to use physical or economic life, we still are making a prediction of the future, something we should be uncomfortable about when we really think about it. None of us knows what will happen tomorrow, much less in 10 or more years. We prefer the illusion of certainty, or expressed another way, we have uncertainty avoidance. Uncertainty avoidance comes from our intolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity. Robert Burton, the former chief of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco-Mt. Zion hospital wrote a book in 2008, “On Being Certain”, in which he explored the neuroscience behind the feeling of certainty, or why we are so convinced we’re right even when we’re wrong. There is a growing body of research confirming this phenomenon. So then, what do we do about asset life? We prefer the comfortable feeling of certainty because of the discomfort of ambiguity and uncertainty.

Some years ago, for SAM, Ype Wijnia and Joost Warners, both then with the Essent Electricity Network in Holland, argued asset management was a strange business. Consider, they said:

Some years ago, for SAM, Ype Wijnia and Joost Warners, both then with the Essent Electricity Network in Holland, argued asset management was a strange business. Consider, they said:

A typical Asset manager works with an asset base that is very old. For example, at Essent Netwerk the oldest assets in operation are about 100 years old, and the average age of the assets is about 30 years. Each year about 3% of the asset base is either built or replaced. Typical maintenance cycles have a period of about 10 years. So, about 13% of the asset base is touched on a yearly basis.

This means our basic job is more like staying clear of the assets and letting them perform their function than it is like actively doing something with them, as the term Asset Management suggests. Therefore it might be wiser to call ourselves asset non-managers.

The strangeness of Asset Management increases further if you look at the portfolio of asset and network policies. From long experience with managing assets, most policies have reached a high level of sophistication and they address not only the general situation but all kinds of possible exceptions which have been encountered over the period since the policy was put in place. Those exceptions have exceptions of their own, requiring further detailing of the policy.

In the life cycle of a policy, attention therefore drifts from the original problem to managing exceptions. This means that as the sophistication of the policy grows, the knowledge about why the policy was developed in the first place diminishes.

Exaggerating a little bit you could say that Asset Managers do not manage most of the assets, and in case they do, they haven’t got a clue why they are doing what they are doing. You would expect a system that is managed this way to collapse very soon, but somehow it does not, as the electricity grid in Europe has a reliability of about 99.99%.

However, this way of managing assets can only work in a stable environment with stable or at least predictable requirements for the assets. Unfortunately, the world we live in is nothing like stable.

Thoughts?

In our current data driven environment, there is still a role for common sense

In our current data driven environment, there is still a role for common sense

A few years ago, using its renewal model, a council was advised that its buildings were 60% overdue for replacement. This came as a great surprise to the Council – but should it have? If true, one would have imagined that there would be many visible signs of major deterioration – non-habitable buildings boarded up for safety, signs of breakdown in buildings still in use (e.g. lifts, plumbing or HVAC not working), union demonstrations, protest movements, etc. If true, this should not have been any surprise to council, their own user experience would have told them that it was true. So what is happening here?

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.” Statistician George Box.

Jeff Roorda, in his post asked ‘why focus on the measurement of physical life using condition instead of looking at function and capacity?’ A very sound question. Function and capacity determine economic life, or useful life (how long we can expect the asset to be of use to us) rather than how long it will physically last. His question is part of a wider range of questions about how we use models.

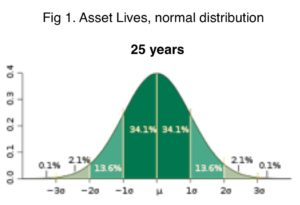

The first thing to note is that renewal models are financial models. They are based on averages of a group and say nothing about the time to intervene (i.e. replace) for any individual asset. When we say that an asset, or an asset component, has a useful life of 25 years, what is really to be understood is that assets of this type may fail at 15 years or even earlier and perhaps as late as 40 years or more but that when we take them as a whole, their useful lives will average out to about 25 years. This is a guide to financial planning.

Because 25 is an average (and assuming we have a normal distribution and not one that is severely skewed) then we can expect that half of these assets will fail before the age of 25 and half will fail after the age of 25, as shown here in figure 1. Thus we cannot assume that just because an asset is greater than 25 years that it is ‘due for replacement’

This is the mistake made by the council, and why it came as such a surprise to the Councillors.

Our instincts may not be infallible but when intuition clashes with the results of a model, it pays to check both our understanding – and our interpretation of the model.

Recent Comments