How hard can it be to make a podcast? Surely, all you have to do is choose a theme. find someone who is willing to talk on this theme, and then ask them questions. The guest then provides the answers. Job done! Many podcasts have used this answer providing format.

But what if you don’t want answers? What if, instead of providing your listeners with opinions or ready made solutions to a given inquiry, you would really like to support their ability to generate inquiry itself?

Asking better questions is a skill we all need to develop for all areas of our life, and for long-living infrastructure decisions in a rapidly changing world it is critical. These decisions impact the lives of many thousands, if not millions, of people and for many decades to come. Once built, they often cannot be un-built except at incredible cost, damage to the environment, and waste of resources. Moreover the ongoing costs of such structures are, as we know, determined by actions taken at the very earliest stages of decision making, when knowledge is lowest!

Some existing solutions will continue to be relevant as the world changes and others will not but how can we tell which is which? Only by asking questions. New questions. Different questions. Lots of questions!

If we ask the same questions we have asked before, we will get the same answers. And if we ask the same questions – blindly – simply because we have always asked them, we will not even be aware of the mistakes we may be making.

But question asking is hard.

Surely not! Any parent knows that young children ask questions naturally – and inexhaustibly! However, at some stage, parents get worn out with continual questions, many of which they do not find themselves capable of answering – ‘why is the sky blue?’ ‘why do people die?’ etc. So mothers start to say ‘Ask your father!’ and fathers say ‘Ask your mother!’ and both say ‘Not now, I’m busy’. In other words we actively discourage question asking at home.

This is compounded at school, where ‘teaching to the test’ has taken hold and teachers know that they have to instill a certain number of facts in their pupil’s heads lest they, themselves, receive a failing grade! In this grading environment, even well intentioned teachers may feel that time out for answering pupil’s questions let alone encouraging more questions, is time that they just cannot afford.

By the time students reach secondary school, they have learnt two things about questions – one, that it is not their job to ask them, and two, that they are to be feared! Studies have shown that in a typical class teachers ask about 90 questions to one or two by students. And the teacher’s questions are designed to test whether what they have taught has been absorbed. Such questions do not lend themselves to the fun of exploration, only the embarrassment and humiliation of wrong answers.

Now the students get a job and it is not long before they come to recognise that asking questions in this environment brings even more problems – asking a question may reveal how much you do not know, or asking a question, particularly of a senior, may seem as a challenge to ‘the way things are done around here’. Better to keep quiet. By this time we have learnt how not to ask questions.

So if ‘not to ask questions’ is a learnt skill, how do we unlearn?

Those of you who are parents might like the story of Isidor Rabi who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1944 for his discovery of nuclear magnetic resonance. He credits his success to his mother who, whenever he returned home from school, would ask ‘Did you ask a good question today? (from Hal Gregerson ‘Questions are the Answer’)

And we can do the same.

We can ask ourselves – did I ask a good question today?

This is what our forthcoming podcast is designed to encourage. Infrastructure decision making urgently needs good questions

– but so do we all!

Quantify the unquantifiable and you change the way that you are able to state goals, track performance, benchmark, evaluate, communicate, and measure outputs not just inputs.

Costs are easy to measure. they are quantitative. The aspects of performance that we are interested in, however, are nearly always qualitative. We want to know what effect our actions have had. Has this action of ours made things better or worse? Such qualitative measures are harder. This is why we are much more likely to default to measuring efficiency (a supply side cost issue) than effectiveness (a demand or user side performance issue). Consider some of the major measures that we use to track how we are going, as a country, or as an organisation – e.g. GDP, life cycle costing. Even benefit-cost analysis will traditionally focus on the measurable dollar amounts and fudge the unquantifiable externalities (both benefits and costs).

We can tie ourselves up in knots trying to express everything in dollar terms and to the extent that we succeed, we may be unaware of the elements inadvently omitted.

So today I want to introduce a technique that was introduced to me 20 years ago by Norman Eason, the Founder and First President of the UK Institute of Asset Management. He gave me this work to publish and I present it to you. If anybody would like to take up the challenge to develop it and take it further, now that technology has made tasks like this so much easier, maybe turn it into an App, I would be happy to put you in touch with the author.

Norman called his technique CAT – Comparative Assessment Technique. It enables you to determine whether qualitative outcomes are improving, whether goals have been reached. – and, if not, how far we are away from the desired end-state (and how much it will cost to get there!)

CAT is based on the simple, but operationally powerful, idea that any qualitative output can be expressed in terms of its worst state, its best, and all possible states in between.

Being able to measure qualitative outcomes/outputs makes it possible to

- Track developments over time

- Compare outcomes with other organisations

- Relate activities to outcomes

- Relate the cost of activities to the improvement in outcomes

So how is it done?

Suppose we use as an example of intangible factors the difficulty in measuring the Cleanliness of a Reception Area. We could list all the possible states, from worst state to best state, as follows: –

Ladder – Cleanliness of a Reception Area

- The filthy nature of the area is seriously affecting our relationships with staff/clients.

- We are always receiving complaints about how filthy the area is.

- We often receive complaints about how filthy the area is.

- We have had complaints about how filthy the area is.

- Although we have not yet received complaints from staff/clients about the dirty condition of the area, we know that this is likely to happen.

- We feel that as a company we are embarrassed by the dirty condition of the area.

- We feel that staff/clients believe that the area is very often dirty.

- We feel that staff/clients believe that the area is usually clean, but is often embarrassingly dirty.

- We believe that staff/clients think that the area is almost always clean.

- We believe that staff/clients think that the area is always clean.

- We never have any problems with the cleanliness of the area.

- We believe that staff/clients think that the cleanliness of the area is always excellent.

- We are always receiving favourable remarks from staff/clients about how clean the area is.

There is no limitation on the number of steps to be used

Note that we have not attempted to limit the number of steps to ten; this would have been the natural tendency, but it is pointless and an artificial irrelevance to the definition of the states. The CAT term for this list is a ladder and each listed state is a step on that ladder.

Setting Target Step

We can now designate the Target Step that the user and supplier agree should be met. Suppose this is Step 11. We never have any problems with the cleanliness of the area.

Setting Actual Step

The user and supplier can now select a step that matches the actual position at any one time. This is the Actual Step. Suppose this is selected to be Step 5. Although we have not yet received complaints from staff/clients about the dirty condition of the area, we know this is likely to happen.

Comparing the Two Steps

We can now obtain a measurement of the actual condition in relation to the target condition, thus Step 5/Step 11 = 0.45 so we are 45% of the way there.

Client-Contractor Relationships

Ladders such as this, especially if developed with joint input, have the potential for far better communication and understanding between client and contractor. It is possible for both to see clearly when a goal has not been achieved (with potential for service improvement) and when it has been over- achieved (with potential for cost savings)

Two interesting things become obvious from our earlier calculation.

- We now have a numerical value of something that previously could only be considered in subjective terms. (Target 45% achieved)

- We now have a decimal value of the relative position of the actual state against the target state, even though we did not start with a scale of ten.

Note:

- Any ladder can be of any length. In fact, the user and the supplier of the service determine the length by incorporating as many steps as are required to fully describe the activity.

- It doesn’t matter that the Target Step is not the top step of the ladder. Target Steps can be moved as new goals are agreed. Note also that there need not be equal increments between steps, although equal steps would be ideal.

- The technique is not restricted to Building Services. Ladders can be used to measure any activity in any one of a number of areas. These areas are not limited to commerce or industry; Local and Central Government are also relevant.

CAT can be applied to the measurement of anything that is intangible

What do you wish to measure?

In assigning CAT to an application area, it is helpful to consider what precisely is being measured. This may seem to be an obvious statement, but there is often confusion in this respect whether tangible or intangible measurements are required.

For example, do you wish to measure the performance of a group, or the results of their work? The two are not necessarily the same. CAT accommodates these more precise definitions of activities by providing for three types of ladder.

CAT can measure

- the performance of a task,

- the effectiveness (or result) of the task, and

- the consequence of the overall activity, e.g., what do the users think of the results?

These ladders can be used separately or combined into groups – any groups that the user organisation feels are important to measure or compare. Also, the activities associated with ladders can have parent/child hierarchies so that, for example, measurements can be rolled up from individuals to groups, to departments, to sites, to divisions and ultimately to the overall company or organisation. In both cases, users also need to agree the weights to be given to each ladder and activity.

Ladders can also be used for comparison in benchmarking exercises. For benchmarking, it is necessary for user organisations to agree on the standardisation of ladders.

If you would like to see the complete report, which contains examples of CAT ladders for consequences, performance, and effectiveness, email me at penny@TalkingInfrastructure.com

Do you know of similar work or perhaps other means of quantifying the unquantifiable?

The first vacuum cleaner was famously the size of a room, now we have the roomba! As we make things smaller we don’t only change the size – we change the properties and hence the possibilities. What does this mean for scaling down infrastructure?

Innovators and entrepreneurs focus on how to ‘scale up’ on the assumption the same benefits will occur but that there will be more of them. Yet when we ‘scale down’, at least if we do this in a major way, we don’t get the same benefits only fewer – we get very different benefits. Take Quantum Mechanics. When we move to an atomic scale the generally observed and accepted rules of physics and mechanics cease to apply. Or nanotechnology where again as we get smaller we get significant – and very useful – differences in material characteristics.

What about infrastructure?

In the past, as we have scaled up, we have reaped greater cost efficiencies, albeit with some greater risks, however most of the features we were interested in stayed the same or got better – cost, reliability. An example would be electricity. For many years, as larger size generators were developed, they provided reductions in both capital and operating costs. Then we networked, joining the production in many separate plants. We developed the national grid. At each stage of scaling up, gains were made.

Now, with the widening spread of digitisation, scaling down is becoming not only a viable option but the desirable option – even for infrastructure. And as we scale down we find that, just as with quantum mechnics, the accepted rules no longer apply, and just as with nanotechnology, new and interesting properties arise.

Again take electricity as an example.

As we move from large, centralised, fossil fuel generation, to small, local solar generation, the first thing that happens is that we change the user- supplier relationship. And with this we change the economic power relationship (no pun intended). Where we used to have one large centralised provider making all the decisions, now we have the possibility of many smaller prosumers in potentially separate networks. The leading electricity providers are recognising that the need for their services has changed – from provision of energy using their own large scale assets, to the management of energy in smaller localised grids and with the assets of others! This may include, as an intermediate stage, large solar farms feeding into a national grid.

This presents a challenge to the grid and its ability.

This challenge was at the root of the perceived (although not explicitly recognised) problem behind the recent Finkel Inquiry. It was not, as was commonly thought, an inquiry into the future of electrical energy, but rather into the future stability of the grid itself, a grid set up to manage supply from mass, centralised, power generation.

Instead of the traditional system of generation- transmission – distribution – use, with solar generation provided more locally, the need for the transmission function (moving electricity vast distances) falls away taking with it the need for substations

As we move from massive large scale to small scale infrastructure, (eg solar energy, or mobile telephony) the whole nature of the infrastructure changes and that gives rise to many new and very interesting possibilities.

It may be that as we ‘scale down’, we change the nature of the supplier-user relationship so much that what used to be a question of how we contained the cost of generation and distribution becomes something quite different – but what?

There is even the possibility that when we are able to develop cheap, effective storage, electricity may cease to be ‘infrastructure’ at all. It may, instead, become an individual resource, something we own like a car or washing machine. Within the next decade it could be that solar cells, (or perhaps solar roof paint) and battery storage are in common use.

Nor is scaling down unique to electricity.

Peter Diamandis tells of Dean Kamen’s “Slingshot,” a technology which can transform polluted water, salt water or even raw sewage into incredibly high-quality drinking water for less than one cent a liter. It uses an evaporative process, effectively boiling the water and then distilling the vapor. It does this in a device about the size of a bar fridge that can use any form of energy – even methane from dung. It is now being distributed across the underdeveloped world by Coca Cola as part of their aim to replenish 100% of the water they use in their drinks. Want to know more? Other technological developments are occurring for the treatment of sewerage.

The upshot of these new technological developments is going to be radical change in the very shape of infrastructure as we know it and an equally radical change in the economics and politics.

What does this mean for infrastructure decision making?

How do changes like this feed into our forward thinking for infrastructure? Or to ask the same question in a more provocative way – what is the future for our existing infrastructure? Do we renew and replace, or do we change?

If you find this an interesting thought, watch for our forthcoming podcast series where we translate the wider world challenges into what we need to think of with respect to infrastructure decision making.

[et_pb_section bb_built=”1″][et_pb_row][et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text]

Last week I suggested why asset management – at its early and basic level – is unstable. Getting your data reliable and customised so that you get credibility with your community is time consuming. But it pays! It not only protect your assets – it also protects your staff!

Last week I suggested why asset management – at its early and basic level – is unstable. Getting your data reliable and customised so that you get credibility with your community is time consuming. But it pays! It not only protect your assets – it also protects your staff!

Let me tell you a story

This is a true story about a certain council in New South Wales. In June 2007, during a wild storm, a section of the road collapsed causing a vehicle with 5 people to plunge into the flooded creek below. A mother, a father, their two children and another woman, a family friend all died.

The cause turned out to be an unlined culvert that had given way. In the subsequent coroner’s investigation it was revealed that:

• The council had been aware of the problem with the road as early as 2002 and had prepared an estimate to reconstruct the entire culvert but that details were never entered into the record management system.

• In 2004, pavement repairs triggered a request by the council’s asset manager to ask for quotes for concrete lining of the culvert with tenders called. But again, the information was not entered into the record system and no follow-up action was taken.

• Emails with quotes for roadwork that may have averted the collapse were not considered official records and were not recorded.

• A key finding of the review was ‘that at the time of the road collapse council’s inadequate reporting practices led to a failure to identify the critical need to upgrade some of its key road infrastructure’

Internet comment on the report of the accident was savage

“Too little too late. Good to see our rate money going towards incompetent council workers who hide behind their computers pretending to be busy. And when the accident did happen they actually had the nerve to try to pass the blame to the state /federal government. This accident should not have happened. For the lazy workers who didn’t do their job properly, how do you sleep at night?”

Is it a case of ‘lazy workers’ or did the system fail them? Unless your system is sound,how would you know? More especially how can they demonstrate their diligence to the outside world?

A poor asset management system puts your staff at risk!

The Central Coast’s ‘Express Advocate’ reported the mother of the young woman whose family perished as saying that she hoped the people who made the human error think about it every night. ‘We certainly do. They have destroyed our family’.

No member of your staff should have to live with this responsibility!

And, although reported as ‘human error’, if you look at the numbers of different people involved in this story, you have to ask yourself whether it is really ‘human error’ or actually ‘system error’.

Now the Coroner’s report was covered in both of the local papers. The reporting was noteworthy for two reasons: One: because both journalists actually used the term ‘asset management’ in their reports, and Two: because both reported that whilst asset was not good at the time of the accident, it was now ‘best practice’.

I was curious.

What had happened to improve asset management so much between the accident in June 2007 and the Coroners Report in March 2009? (less than 2 years) And what was it that impressed the journalists so much that they both reported that the council was now ‘best practice’ in asset management.

I decided to visit the council and find out. When I walked into the foyer, on the wall facing the entrance was their ‘mission statement’. It said simply “We aim to be a council that the community is proud of” and underneath it said “We are not there yet!”

That told me a lot about the current attitude of that council and their determination to get better.

Then I met with the Asset Manager and his Director of Information Services. Both were extremely open, articulate, knowledgeable – and very enthusiastic about asset management. They knew they had to improve their asset information and had taken serious steps in this direction.

But they also knew that improving asset information alone is not enough. They knew they also had to understand and improve their processes. And this is where they really shone. They analysed and streamlined each of their processes. There were dozens of these processes, each reproduced in large A3 size – and laminated, indicating that these were for constant use. They were bound in sections relating to different functions.

Mapping is a great way to understand your processes – and a great way to show others that you understand them! My guess is that it was these graphics that so impressed the journalists!

Taken together,

- greatly improved information +

- A positive, action-oriented, attitude – as expressed by the foyer plague and the confidence and knowledge of the Asset Manager and his Director of Information Services +

- Understanding of Asset Management Processes – as illustrated by the process maps,…

all added up to a situation where two different journalists from separate papers, in reporting the story of council failure, would both modify their criticism by making it clear to their readers that the council’s asset management was now ‘best practice’.

But there was an even better result.

After the coroner’s findings had been handed down with all the attendant publicity, the Sydney Morning Herald reported on yet another culvert in poor condition in the council area. In ordinary circumstances you would have expected the press to have a field day with this. But it didn’t happen.

Despite the obvious cracks and poor condition of the culvert, the Sydney Morning Herald’s journalist provided very balanced and moderate coverage. He quoted the consulting engineer’s findings, made some criticisms of the council but then tempered the report with the recognition that the cost to repair the problem was high relative to the annual budget; actually quoted figures, and comment by other councils about this problem and recognised that a large part of the problem was that the roads were handed over to councils by the State Government, who had previously had responsibility for them, with insufficient maintenance funds attached.

What price would you pay for fair media coverage?

Next week I look at why even good asset management is not enough. Why we have to ‘go beyond’.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

I have long been interested in one particular aspect of the history of asset management. Why was it that agencies would so often progress to the stage of being the envy of all others in terms of their asset management – only to collapse and have to rediscover everything they previously knew? I suspected that there must be something inherently unstable about asset management – and there is! Here I explain what the problem is and how you can make sure it doesn’t happen to you.

You are going to come across a lot of definitions of asset management. Maybe you already have. All have validity. But the one that I favour at the moment has a focus not on what asset management does – but rather on what we get out of doing it!

I look at asset management as ‘a series of process and information improvements that enable organisations to see not only the likely consequences of the decisions taken today – but also of the actions not taken.’ You can argue with this definition, but bear with me, because you will see how it can help.

When armed with a knowledge of likely consequences you can make better decisions. You may not have enough money to do everything, but if you understand the consequences you can be reasonably confident that the things you are doing are at least of greater value to your organisation or community than the things you are not. Even more importantly, you can demonstrate this to others.

Asset management protects you. If you are a councillor, it protects you from pressure by lobbyists and those who would have you spend council resources in ways which you know are sub-optimal. If you are an administrator, it enables you weigh up different uses of your limited resources. If you are a manager responsible for assets, it enables you to know what to do that will best meet the service needs of the community.The key word is ‘consequences’.

When you can tell what is likely to happen next as a result of the actions you take today – and of your inactions – you are able to make better decisions and make them with confidence. And when you are able to demonstrate this to others and gain their confidence, life becomes much more enjoyable.

Driving in the Dark

Driving in the Dark

Without asset management, you are operating in the dark. It’s like driving at night with your headlights showing you just a few metres of the coming road. You are only able to see a little way ahead, and all of your decision making, whether on short or long term goals, is constrained by having such a limited view. So you have to move cautiously, never quite sure what those shadows mean, or what is coming next. And you can easily miss your turning and have to make time wasting course corrections. Or at worse, run into something with expensive, maybe fatal, results.

Introducing asset management is now like switching on your high beam.

Introducing asset management is now like switching on your high beam.

Suddenly, with a better view of the likely consequences of your actions, you can now see a long distance in front. You can move forward more confidently, make better decisions, and avoid potential problems, because you understand the likely consequences of actions and inaction.This is very exciting and it is not difficult to see why asset management creates evangelists. Many of you will have experienced this in the early stages of asset management, when, perhaps for the first time, you now have an overall view of your asset base, a better understanding of what you have, what condition it is in, and what its value is. This gives you a completely different view of what you can do – and it is pretty heady stuff.

But a word of caution!

What I have learnt is that when you reach this stage, you must not stop. The High Beam stage is unstable. When you are on the road, any approaching vehicle can force you to switch them off. Similarly when you are starting asset management, and you adopt generic assumptions about asset lives and desired service levels to get yourselves started, you get a ‘great leap forward’. This is the ‘switching on the high beams’ stage. It enables you to make progress quickly.

As in all things, easy come – easy go!

When things get tough – the asset management equivalent of the oncoming traffic – you can no longer rely on those generic assumptions and service levels. In times of trouble, such as missed grants, unexpected and unfunded asset renewals, in fact any difficulty, your staff and your ratepayers need to have full confidence in the reliability of your system and this means that you need to move on from the generic data and develop information that is credibly yours. In other words, you need to customise, to make the service levels and associated asset lives your own.

To do this you need to work with your community to develop service levels that are widely understood and accepted and can withstand criticisms.

Your asset data needs to reflect these service levels and to demonstrate the reliability that comes from documented, efficient, update mechanisms. Your asset lives need to reflect your own local conditions and known maintenance histories. And you need robust processes to ensure that all new asset acquisition reflects your strategic directions.

This takes effort, commitment – and time.

However, once you have done this, you are largely failure proof. By the time you have developed a good understanding throughout your staff from field staff to CEO, board or councillors, by the time you have good, up-to-date data, and by the time you have the confidence that this brings, then your asset management is secure.

You have successfully navigated the instability phase and come out safely on the other side. This stage of asset management is like adopting a Satellite Navigation System. Now you can analyse all the options and choosing the optimum course is easy.

Moreover, when you get here you won’t want to stop. Now, asset management improvement for the benefit of your community will simply be the way you do business and you will enjoy always seeking to do better. The Road Ahead is now clearer and you travel it with confidence.

Questions?

- Where are you on the road to sound, reliable asset management?

- Are you still at the stage where you are using general purpose asset lives, gleaned from somewhere else? Or have you customised?

- Have you established accountable service levels? And are these service levels clearly and transparently connected to your asset life data? Do they inform your understanding of effective age and time to renewal?

- Have you reviewed, updated and streamlined your asset management practices?

Think this is too much work?

Then be sure to read next week’s post where we look at the danger not only for your assets, but for your staff ,of not getting to this stage of asset management.

Next Week: AM Protects – your staff!

Data, Facts and Evidence

What makes a ‘fact’ a fact? What makes evidence, evidence?

The fictional detective Joe Friday is famous for something that he actually did not say – “Just the facts, Ma’am”. Many a CEO used to request the same. But is it possible to lift ‘facts’ out of context and for them still to be meaningful? Take Julius Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon in 49 BC. Many others crossed the Rubicon both before and after but their crossings are not recorded as ‘facts’. So why Caesar? Caesar’s crossing with his army became a historical ‘fact’ worthy of remembering only because it is considered to have led to the Roman Civil War, which ultimately resulted in Caesar becoming dictator for life and the rise of the imperial era of Rome. In other words, it is the ‘context’ that makes this particular crossing of the Rubicon a ‘fact’.

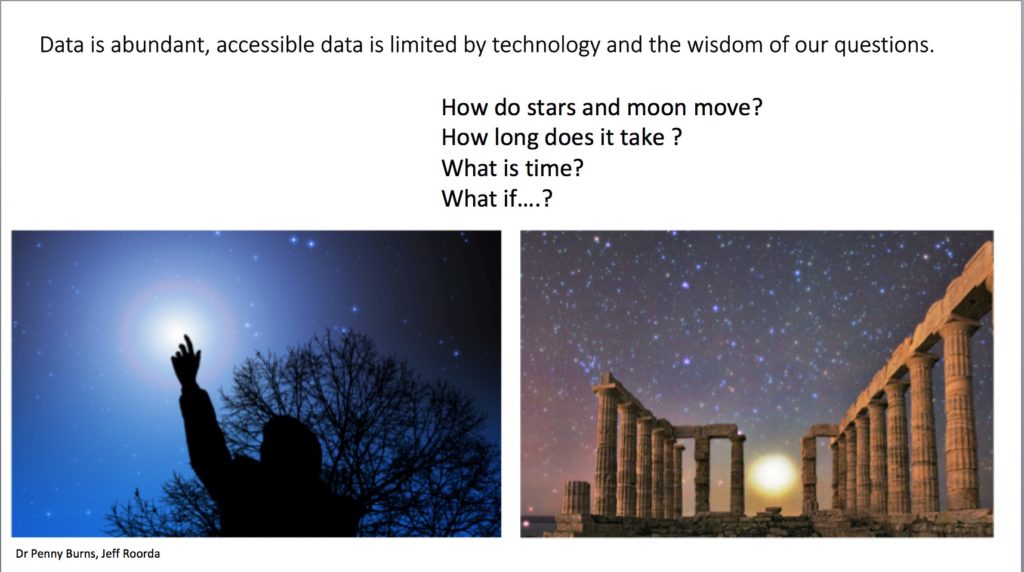

Data is meaningless, until…

Data, by itself, is without meaning. It is mere blibs – on paper or on screen. It only yields meaning when interrogated. Ask the wrong questions and we get wrong answers. In his presentation to the IPWEA Congress in July, Jeff Roorda observed that when Copernicus proposed that the earth moved around the sun, the data that had been collected about the movement of the stars and the sun did not change. It was just that it was interrogated through a different question.

Not all data is created equal

While natural data may remain constant (although perhaps not well understood), the same is not true of data that we use today in our management systems. That data has been selected, chosen and shaped by the questions that we have asked of it in the past. For example, if the focus of our questions has been on the current value of our asset portfolios, we may have calculated, and recorded as data, the depreciated value but have failed to record the age distribution without which we have no way of knowing what that value means in terms of renewal timing. If we recorded our assets in historical cost terms, we may be able to account for their accuracy by referral to the invoices of the time, but it yields no management information. If we recorded our maintenance expenditures by site but not by what was done on that site, we may know where it has gone, but we won’t know what was done and so what we may have to do later.

Today, our ability to access and analyse data enables us to answer old questions with more precision. This is exciting. The easy thing to do is to collect more of what we have collected in the past and to address the same questions. In other words we can use new data to answer our old questions, questions that were themselves shaped by the data limitations at the time.

So, an even more important question might be – are we prepared to ask new questions that cannot be answered simply by inserting more data in our current current data frameworks?

Are we prepared to rethink our data frameworks? Our thinking models?

With new technology we can now create an abundance of data very cheaply, not only historical but real time data. In fact, we may well argue that anything we can think of we can now collect data on. To take advantage of this, we cannot let ourselves be hamstrung by the assumptions that have ruled in the past and the questions that these assumptions have generated. But having – at great expense – assembled the data we now possess – how do we ask questions that move beyond the models we have already developed?

This is one of the areas that we will be examining in our future podcast – “Talking Infrastructure: creating better questions”

Yesterday I posted IDM in Pictures 3/12. IDM stands for Infrastructure Decision Making. You can think of IDM either as the next stage after strategic asset management or as an intermediary stage between 20th century physical infrastructure and a 21st century that will be increasingly cyber or cyber augmented, but the shape of which we do not yet know. Infrastructure decision making is about asking those questions that will help us make the adjustments we will need to make.

Yesterday I posted IDM in Pictures 3/12. IDM stands for Infrastructure Decision Making. You can think of IDM either as the next stage after strategic asset management or as an intermediary stage between 20th century physical infrastructure and a 21st century that will be increasingly cyber or cyber augmented, but the shape of which we do not yet know. Infrastructure decision making is about asking those questions that will help us make the adjustments we will need to make.

For example, consider the rise of e-sports, a.k.a competitive video gaming. What impact might this have – on physical sports and on our sports infrastructure? Already a $1.5 billion business, it is increasing at 30% p.a. and projected to continue this rate of growth for at least the next five years. How many of our recent stadiums and those now being built have factored in this rate of growth for e-sports – and the possible concommitant impact on physical sports? So far it has mainly affected Asia and North America. However Australia joined the excitement early this year with major tournaments in Melbourne and Sydney. Do our current sports stadiums lend themselves to housing these events? The physical requirements of e-sports in Sydney (pictured) required the design and construction of a purpose-built elevated stage housed in a movie theatre complex. E-sports require high speed internet access and present high intensity light shows, music, dancing along with the video gaming competition. In Asia and North America they can attract crowds of 100,000.

In times of uncertainty we often seek comfort in resorting to what we have always done and are therefore confident that we know how to do. This may give temporary relief from the stress of the unknown but it only pushes the decision making further out whilst making the decisions harder when they come due again, and this is likely to be much sooner than we think. The consequence of doing this in the recent past may be why we are now hearing the term ‘playing catch up’ from our political pundits like Jeff Kennett. I don’t like this term, or the idea it implies. Why catch up when by the time that we do, what we are catching up with will already have passed?

The earlier we pay attention to future issues and start thinking – and talking- about the changes needed – in mindset, technology, principles and practices – the easier our adjustment task will become.

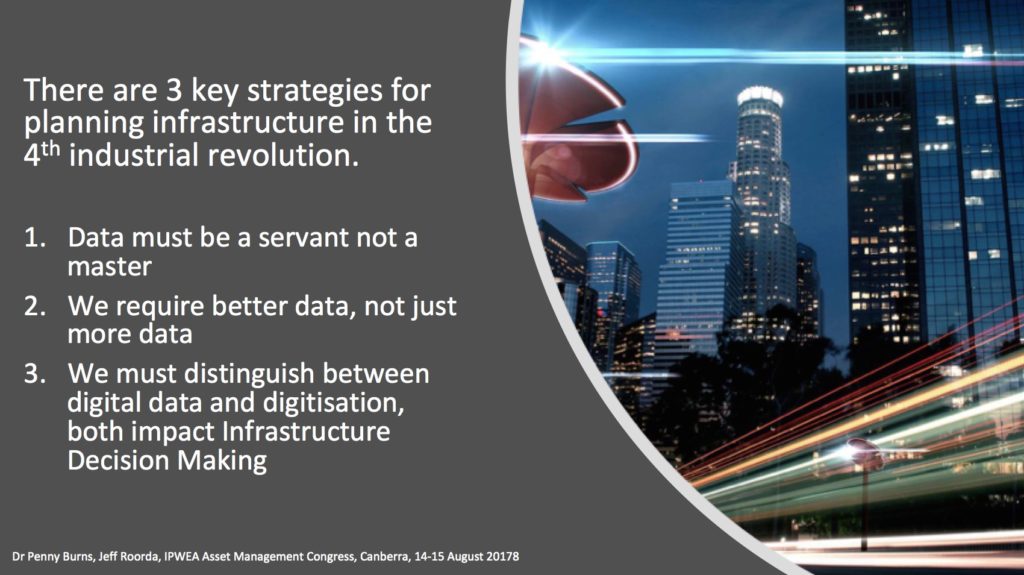

Big data is a route to Abundance, but let us take care, data makes a great servant but a dangerous master.

If we respond to data outputs uncritically we make data our master. Yes, algorithms are becoming ever more complex and difficult to understand – and therein lies the problem. Unless we are able to understand HOW a decision was made, algorithms are just dead dangerous. There are really serious problems of people being denied access to medical or social assistance or being jailed because an algorithm deemed it so. Less serious – but funny! – is the story of two booksellers on Amazon using pricing algorithms that resulted in a 1992 out of print book on the evolution of flies rising to over $28m. A post graduate student interested to buy the book first noticed that where second hand copies were listed at $35, new copies were then over $2,000. When he went back the next day, the price had risen even more, and so it continued. Studying the prices, the student realised that one seller had set his pricing algorithm to be fractionally less than his main competitor in order to attract sales. the other bookseller had set his algorithm to price this book at slightly more than his main competitor. Why? We don’t know but the student suggests (in his blog where he writes it all up) it might have been because the seller didn’t actually have a copy of the book and would have to source it should anyone order. Since the premium of the one seller exceeded the discount of the other, the price kept rising. It took this research student to notice what was happening – not the booksellers, who were, of course, on autopilot. What damage could occur in your work if you are on autopilot?

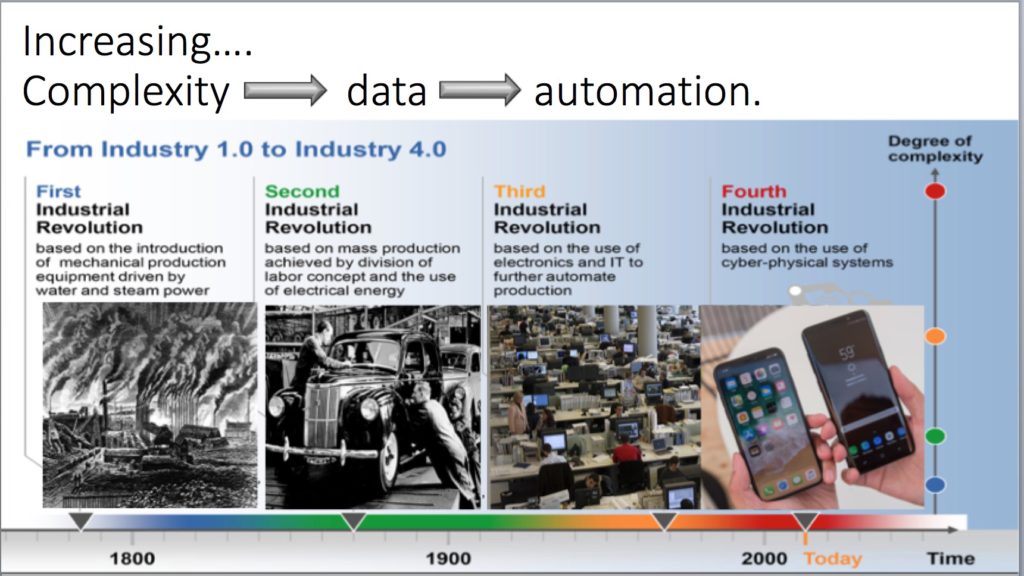

The ability of big data to deal with increasing complexity is nevertheless a great advantage. Consider how we have moved since the first industrial revolution.

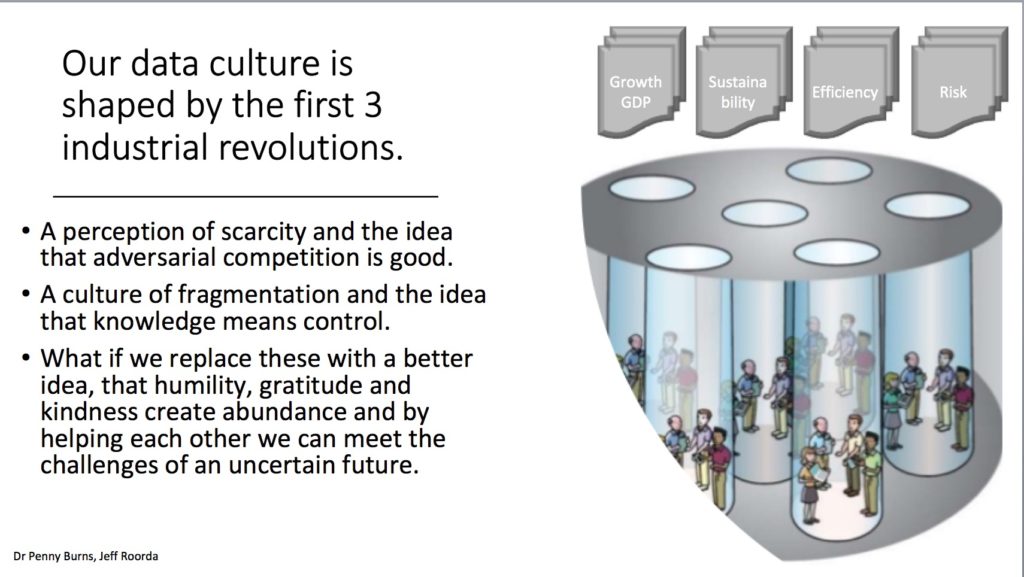

Our data culture is shaped by the first 3 revolutions. This has given rise to two attitudes or mindsets that are no longer acting to our advantage.

- A perception of scarcity and the idea that adversarial competition is good. But we are about to embark on a new world of abundance – as well described in Jeremy Rifkin’s “Zero Marginal Cost Society”. This is requiring businesses to change their business models. We know it as ‘disruption’ but it is more than that, it is opportunity.

- With increasing specialisation we have developed a culture of fragmentation and the idea that knowledge means control. Now that we are able to share knowledge so much more freely, we are able to develop better models, a more fruitful culture.

- This means that we can start to explore replacing these old ideas with a better idea, that humility, gratitude and kindness create abundance and by helping each other we can meet the challenges of an uncertain future. These are not really new ideas. During and just after the second world war, Londoners who had survived the blitz, now faced the problem of recovery. Instinctively they knew that, just as they had survived the war through helping each other, this was also the way that they would meet the uncertainty of the future. But as people became richer, they became more selfish and the initial rate of gain slowed. The way of the future is through collaboration. Harvard studies, as reported by Shawn Achor in “Big Potential”, have clearly demonstrated that teams of collaborating individuals have it all over geniuses. In fact a team of average intelligent people who ‘get on with each other’ well exceed the performance of a team of geniuses.

- This is the real message of ‘big data’ – together we can do more than we can do alone.

The possibilities of big data are impressive but let us not get carried away.

Not only is there the danger of trusting in the results of data manipulation that we do not understand (cf the many studies showing the dangers of ‘private’ algorithms that are not open to analysis), but there is the greater danger that we put our faith in aiming at ‘data’ outcomes (e.g. KPIs) rather than people outcomes.

So let us put our effort into better measurements of what really matters – better (i.e. more relevant) data. This will inevitably mean using non-dollar measures – and judgement.

Discussion today tends to conflate the benefits of greater use of digital data and digitisation itself. Both are valuable, and both impact infrastructure decision making, but they are not the same.

There is currently much discussion of loss of work opportunities through the use of robots. If our decisions are driven purely by data, then robots can do a great job. But if we want our decisions to include values such as kindness, compassion, and fairness, then we need people.

We appreciate the benefits of big data but do we really want to live in a world without kindness, compassion and fairness?

Infrastructure spending is often justified on the grounds that we are ‘building for the future’. If we truly believe this, and if we are concerned to provide a safe and prosperous world for our children to inherit, then we are running out of time. This is the conclusion of “No Time for Games: Climate Change and Children’s Health’ by Doctors for the Environment Australia where they describe the many ways in which periods of excessive heat, disease carrying flood waters, storm events and rising sea levels are seriously impacting the physical and mental well being of our children. This is not a hypothetical. It is happening now. And the recent NEG decision to support coal under the guise of providing ‘reliability’ for renewables is, unfortunately, symptomatic of the hypocrisy of the time.

Infrastructure spending is often justified on the grounds that we are ‘building for the future’. If we truly believe this, and if we are concerned to provide a safe and prosperous world for our children to inherit, then we are running out of time. This is the conclusion of “No Time for Games: Climate Change and Children’s Health’ by Doctors for the Environment Australia where they describe the many ways in which periods of excessive heat, disease carrying flood waters, storm events and rising sea levels are seriously impacting the physical and mental well being of our children. This is not a hypothetical. It is happening now. And the recent NEG decision to support coal under the guise of providing ‘reliability’ for renewables is, unfortunately, symptomatic of the hypocrisy of the time.

We can regret the loss of leadership as David Shearman did in his excellent article in the ABC Adelaide news this morning “Climate change is World War III, and we are leaderless” and urge our elected members to do more, and we should do this.

But maybe we need to DO more? Maybe in our leaderless world we need to take leadership into our own hands? In the past we have tended to leave large scale infrastructure decisions to others. Perhaps this now needs to change? No Time for Games has this to say about Infrastructure:-

Infrastructure and risk reduction

‘Protecting children’s health also requires risk reduction in sectors other than health such as housing, agriculture, urban planning and transportation. Improvement in urban and regional planning design such as relocation away from areas at risk from natural disasters or sea-level rise, or better housing design to reduce heat impacts, are examples of reducing the risk of climate health impacts to children.

‘Protecting children’s health also requires risk reduction in sectors other than health such as housing, agriculture, urban planning and transportation. Improvement in urban and regional planning design such as relocation away from areas at risk from natural disasters or sea-level rise, or better housing design to reduce heat impacts, are examples of reducing the risk of climate health impacts to children.

Reducing socioeconomic disadvantage in children and improving baseline health, food security and education are fundamentally the best form of climate change adaptation due to their role in making children and families more resilient and better prepared for the environmental risks brought by climate change’

We can all have a say in promoting these changes, directly where we are able, and in voting for measures which improve them and against those which don’t.

That the increasing health effects of climate change disproportionally affect children challenges the most fundamental call of humanity, to nurture its young.

Failure to act is a major intergenerational injustice

My thanks to Ian Spangler for drawing my attention to this.

Recent Comments